Thyroid gland involvement by Koch's bacillus is an extremely rare condition.1 The number of cases reported in recent years is very low, even in Asiatic areas where the prevalence of tuberculosis is high.2 Differential diagnosis of masses in the midline of the neck should include thyroglossal duct cyst, lipoma, thyroid carcinoma, and cervical adenopathies of thyroid isthmus.3 This condition tends to be underdiagnosed because of the rarity of tuberculous thyroiditis. The case of a 57-year-old male with clinical signs of goiter, neck adenopathies, and dysphagia is reported below.

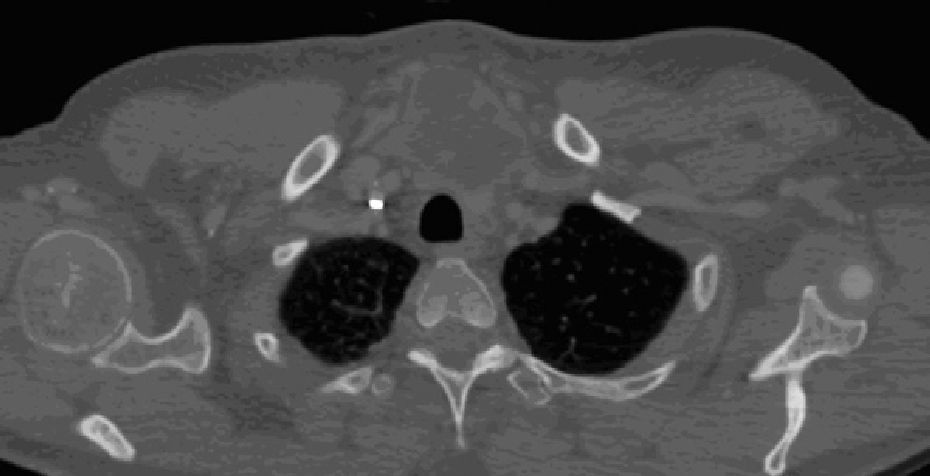

A 57-year-old male born in Bolivia who had been living in Spain for 20 years reported the gradual occurrence during the previous three months of a hard, painless mass in the midline of the neck. During the previous month, stone-hard, immobile, and tender right jugular adenopathies had also appeared, associated with progressive dysphagia to solids in the previous weeks. The patient also reported the loss of 10kg of weight during that period with fever, mainly occurring at night, chills, and profuse sweating with no other associated symptoms. The patient provided the results of tests previously made at another center, including fine needle aspiration leading to a diagnosis of lymphocytic thyroiditis, undetectable anti-thyroid antibodies, and a neck ultrasound showing two masses dependent on the thyroid gland, of which the right lobe mass measured 65mm×33mm×19mm in size and the left lobe mass 55mm×32mm×40mm. When examined by us, the patient was afebrile and in a good general condition, and was found to have a big suprasternal mass in the anterior neck 6cm in largest diameter not affecting the overlying skin, mobile upon swallowing, and with no audible murmur or systolic thrill over it (Fig. 1). Hard, painful, and immobile adenopathies 3cm at largest diameter were also palpated in the right jugular region, as well as multiple 1-cm adenopathies in the right supraclavicular region. Chest X-rays showed no pathological findings. A complete blood count revealed 7800 white blood cells/m3 and a normal differential count, as well as a hemoglobin level of 11.3g/dL with a pattern of increased cholestasis enzymes and moderately increased serum adenosine deaminase activity with serum thyroglobulin levels within the normal range. Thyroid function tests at that time showed subclinical hypothyroidism with normal free thyroid hormones and a TSH level of 9.42μIU/mL (0.34–5.6). An additional ultrasound-guided puncture of the midline mass was performed, revealing multiple bilateral adenopathic clusters and a big intrathoracic, hypoechoic, heterogeneous, ill-contoured neck mass. Radiographic findings were confirmed by a computed tomography scan showing the neck mass, adenopathies of pathological size and necrotic appearance in the neck, mediastinum, and subcarinal region, and very small peripheral lung lesions (Fig. 2). A pathological examination of the puncture sample, of a caseous appearance, was not conclusive, showing abundant coagulative necrosis, few thyroid follicular cells, and nonspecific inflammatory cells. Thyroglobulin measurement in exudate was markedly positive (40ng/mL), highly specific for thyroid tissue in the samples, while the search for bacilli in the exudate using the Ziehl test was negative. Laryngoscopy showed no changes in the area examined.

Finally, a polymerase chain reaction positive for Mycobacterium avium complex provided a definitive diagnosis.

The patient started antituberculous treatment with four drugs: isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. Two months later, percutaneous drainage of the right thyroid lobe was performed due to the persistence of the mass. The subsequent course was satisfactory after antituberculous treatment was completed. Prior lesions disappeared, and thyroid function was in the range of persistent subclinical hypothyroidism, requiring low doses of oral levothyroxine.

Thyroid gland involvement by tuberculosis is rare. It was first reported by Lebert in a patient with disseminated disease in 1862.2 Later, in 1932, Rankin and Graham detected involvement in 21 of 20,758 thyroid glands examined in a Mayo Clinic series corresponding to the period 1920–1931 (0.1%).4 The low incidence of this condition is due to the intrinsic capacity of thyroid tissue to withstand infection.5 Various theories have been proposed to explain these findings, including bactericidal activity of the thyroid colloid material, high blood flow, and gland oxygenation and high iodide levels, although none of them has conclusively been demonstrated.6

Thyroid involvement is usually secondary to hematogenous dissemination of the bacillus or to continuous propagation from an adjacent site, usually mediastinal, paratracheal, or cervical adenopathies, including nodal involvement of the thyroid isthmus.7 Primary thyroid gland involvement is even rarer.8 Its clinical presentation is highly variable, and may consist of diffuse goiter with abundant caseous necrosis, a solitary thyroid nodule, the widespread involvement in the setting of miliary tuberculosis, or diffuse fibrosis difficult to differentiate from de Quervain's thyroiditis.2 The occurrence as an acute abscess has more rarely been reported.7,9 Dyspnea, dysphagia, or dysphonia due to recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy may also be associated as a result of mass compression.3 The condition is rarely included in differential diagnosis of intrathyroid masses because of its exceptional occurrence.8

Thyroid function changes have also occasionally been found in cases reported in the literature. There have been rare reports of myxedema due to massive gland destruction, and more frequently reports of hyperthyroidism due to excess hormone release, although the vast majority of patients have thyroid hormone levels within the normal range. We found in our patient a moderate progressive increase in TSH levels with free T3 in the lower normal limit and free T4 within the normal range persisting over time during the disease period and after treatment.

The final diagnosis of tuberculous thyroiditis requires that microbiological involvement be shown in the thyroid gland or in a histopathological study. The latter must show the presence of granulomas with central caseous necrosis, Langhans cells, and surrounding epithelioid cells. The direct examination of aspiration after staining for acid-fast bacilli is rarely diagnostic.10 Diagnosis is usually based on microbiological culture in special media (Löwestein, Middelbrook 7H9, BACTEC). In our case, the presence of the bacillus was shown by genomic amplification of Mycobacterium avium complex using a polymerase chain reaction, which is highly sensitive and specific for this microorganism. A Löwestein culture performed weeks later was positive for the mycobacterium.

As regards the way in which the thyroid gland of the reported patient could have been affected, it appeared most likely that secondary involvement occurred from regional adenopathies, including that of the thyroid isthmus, possibly through a fistula between both systems, followed by the formation of necrotizing granulomas and secondary gland destruction.

Chemotherapeutic drugs against the bacillus have previously been used to treat tuberculous thyroiditis, associated with resection of the involved area or with abscess drainage when required. There is recent evidence that antituberculous drug treatment may be effective in eradicating the infection in the absence of other procedures.

Thyroid tuberculosis is an exceptional cause of goiter requiring a high clinical suspicion, particularly when associated with cervical adenopathies and/or constitutional symptoms. Current methods may allow for specific, minimally invasive diagnosis, and medical treatment and percutaneous drainage represent safe and effective management options. This case is reported as an example of this.

Please cite this article as: Cuesta Hernández M, Gómez Hoyos E, Agrela Rojas E, Téllez Molina MJ, Díaz Pérez JÁ. Tuberculosis tiroidea: causa excepcional de bocio compresivo. Endocrinol Nutr. 2013;60:e11–e13.