Endogenous or metastatic endophthalmitis due to haematogenous spread from an extraocular septic focus represents less than 10% of all forms of endophthalmitis.1 Diabetes, immunosuppression and the use of parenteral drugs are well established risk factors. Bilateral involvement is rare and is more commonly seen in forms involving fungal aetiology.1 Here we describe a case of bilateral endophthalmitis as the first manifestation of pneumococcal endocarditis and discuss our literature review on this clinical scenario.

The patient was an 80-year-old woman with a history of high blood pressure, morbid obesity, sleep apnoea-hypopnoea syndrome and obesity-hypoventilation syndrome, with chronic respiratory failure and permanent atrial fibrillation. A transthoracic echocardiogram performed one year prior showed a degenerative aortic valve with slightly decreased opening and mild regurgitation. Her usual treatment consisted of furosemide, acenocoumarol, candesartan and omeprazole. She had received the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine at the age of 66 years. The patient was assessed in the Accident and Emergency Department for general malaise, feeling hot and cold, drowsiness and sharp decrease in visual acuity in both eyes for 48h. Physical examination revealed an axillary temperature of 39°C with no data to suggest haemodynamic instability (blood pressure of 142/75mmHg, heart rate of 98bpm), a systolic murmur in aortic focus of intensity III/VI and bilateral ankle oedema. Eye examination revealed hyperaemic conjunctiva with transparent cornea and hypopyon in both eyes (more evident in the right), while the fundoscopy did not allow visualisation of the retinal structures due to opacity of the anterior media. Blood analysis showed thrombocytopenia (76×1000platelets/μl), deterioration in renal function (serum creatinine: 1.60mg/dl) and elevated C-reactive protein (23.5mg/dl [normal range: 0.10–0.50]). In view of suspected endogenous endophthalmitis, the patient was started on intravitreal treatment with ceftazidime and vancomycin (0.5ml), in addition to systemic antibiotic therapy with piperacillin/tazobactam (4/0.5g/6h), levofloxacin (500mg/12h) and linezolid (600mg/12h). An emergency transthoracic echocardiogram revealed a mobile Image 1×1.3cm in size in the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve protruding towards the left atrium, plus a second smaller lesion (0.5×0.5cm) in the posterior leaflet, which was protruding towards the ventricle. These findings were compatible with endocarditis vegetations. In the two sets of blood cultures extracted when the patient arrived (time to positivity less than 12h), the preliminary identification was of Gram-positive cocci in chains, so the systemic treatment was changed to ceftriaxone (2g/24h) and ampicillin (2g/h), continuing linezolid. In the end, isolation of Streptococcus pneumoniae was confirmed, with intermediate sensitivity to penicillin G (minimum inhibitory concentration: 1mg/l), so the ampicillin was discontinued. A surgical approach to the endocarditis was ruled out because of the patient's poor baseline functional status and high burden of comorbidity. There was a slight improvement in the endophthalmitis in her right eye, with a decrease in hypopyon (1mm). However, over the following 48h the patient's clinical situation progressively deteriorated, resulting in her death due to multiple organ failure.

Endogenous endophthalmitis is an uncommon complication in the course of bacteraemia and tends to be devastating in terms of visual prognosis, with any delay in diagnosis being a further contributory factor. The microorganism penetrates the eyeball through the vessels of the posterior pole and, after crossing the blood/eye barrier, it spreads from the retina and choroid to the vitreous body and, finally, the anterior chamber. The sources of bacteraemia most commonly reported in the literature include intravascular catheters, endocarditis and, more rarely, liver abscesses, while Klebsiella pneumoniae (particularly strains of serotypes K1 and K2 carrying the magA gene associated with hypermucoviscosity in Asian series), Staphylococcus aureus and streptococci are the most common agents.1

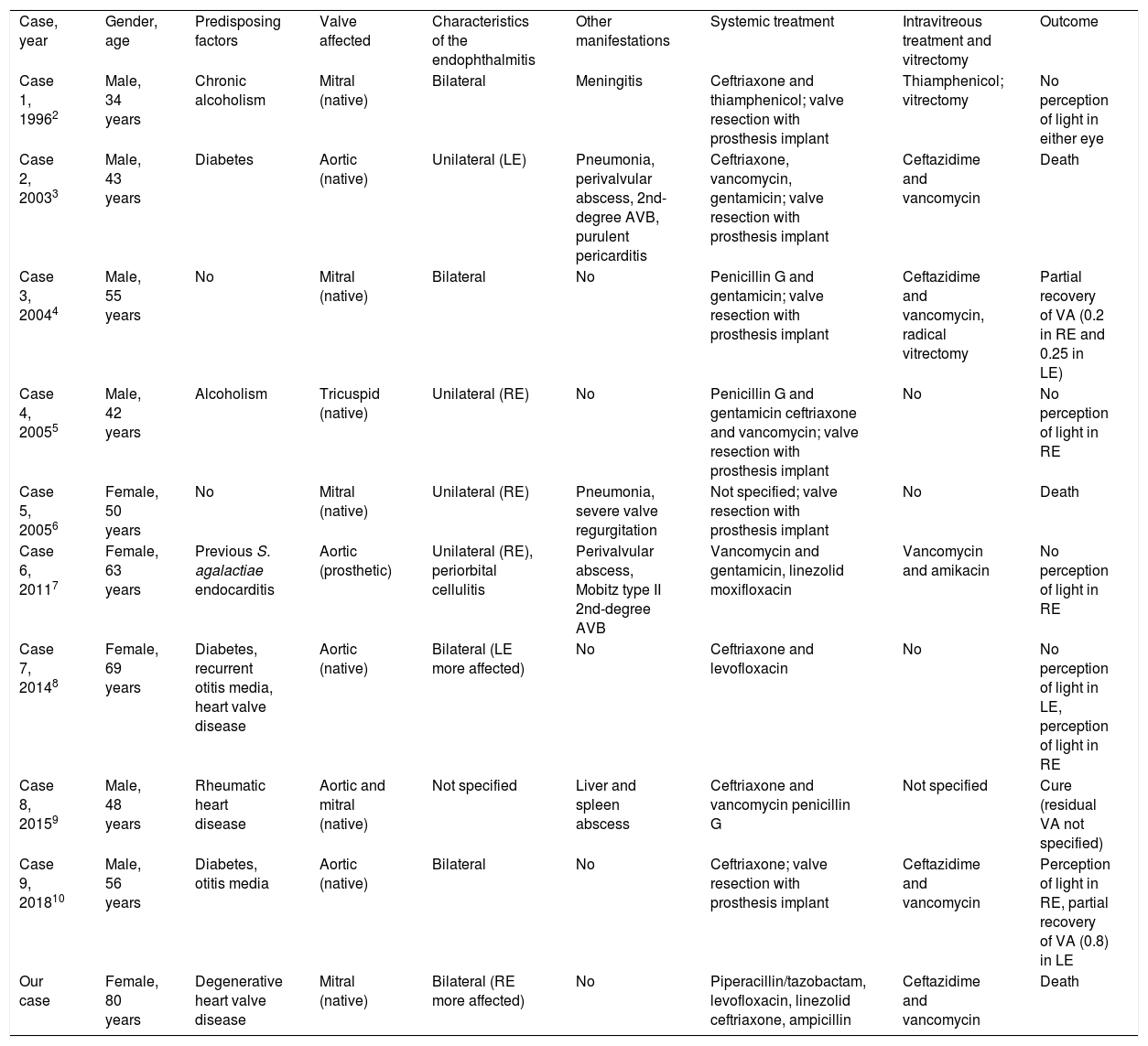

Although Streptococcus pneumoniae has been described in some series as the fourth leading cause of endogenous endophthalmitis,1 bilateral involvement as a form of presentation of pneumococcal endocarditis is unusual. We searched the PubMed database (MeSH terms: “Streptococcus pneumoniae” or “pneumococcus” plus “endophthalmitis” plus “endocarditis”), and did a manual review of the list of references of the identified articles, revealing nine additional cases2–10 reported up to September 2018 (Table 1). There was a predominance of native valve endocarditis2–6,8–10 and in four patients (40%) other concurrent manifestations of invasive pneumococcal disease were associated, such as meningitis,2 pneumonia3,6 and visceral abscesses.9 The endophthalmitis was bilateral in half of the series. In six of the cases with available information (66.7%), intravitreal antibiotic treatment was administered,2–4,7,10 although the utility of this strategy in endogenous endophthalmitis is less established than in exogenous forms, probably due to the low incidence of the complication. For that reason, systemic treatment should include antibiotics with good penetration into the eyeball, such as linezolid or fluoroquinolones.7,8 Only two of the cases reviewed involved vitrectomy.2,4 However, vitrectomy should not be delayed in the forms caused by aggressive microorganisms such as S. aureus or K. pneumoniae.1 The outcomes were adverse in general terms, as two patients3,6 (in addition to our case) died, while among the survivors, there was only partial recovery in visual acuity in three of the 10 affected eyes.4,10

Cases reported in the literature of endogenous endophthalmitis in the context of pneumococcal endocarditis.

| Case, year | Gender, age | Predisposing factors | Valve affected | Characteristics of the endophthalmitis | Other manifestations | Systemic treatment | Intravitreous treatment and vitrectomy | Outcome |

| Case 1, 19962 | Male, 34 years | Chronic alcoholism | Mitral (native) | Bilateral | Meningitis | Ceftriaxone and thiamphenicol; valve resection with prosthesis implant | Thiamphenicol; vitrectomy | No perception of light in either eye |

| Case 2, 20033 | Male, 43 years | Diabetes | Aortic (native) | Unilateral (LE) | Pneumonia, perivalvular abscess, 2nd-degree AVB, purulent pericarditis | Ceftriaxone, vancomycin, gentamicin; valve resection with prosthesis implant | Ceftazidime and vancomycin | Death |

| Case 3, 20044 | Male, 55 years | No | Mitral (native) | Bilateral | No | Penicillin G and gentamicin; valve resection with prosthesis implant | Ceftazidime and vancomycin, radical vitrectomy | Partial recovery of VA (0.2 in RE and 0.25 in LE) |

| Case 4, 20055 | Male, 42 years | Alcoholism | Tricuspid (native) | Unilateral (RE) | No | Penicillin G and gentamicin ceftriaxone and vancomycin; valve resection with prosthesis implant | No | No perception of light in RE |

| Case 5, 20056 | Female, 50 years | No | Mitral (native) | Unilateral (RE) | Pneumonia, severe valve regurgitation | Not specified; valve resection with prosthesis implant | No | Death |

| Case 6, 20117 | Female, 63 years | Previous S. agalactiae endocarditis | Aortic (prosthetic) | Unilateral (RE), periorbital cellulitis | Perivalvular abscess, Mobitz type II 2nd-degree AVB | Vancomycin and gentamicin, linezolid moxifloxacin | Vancomycin and amikacin | No perception of light in RE |

| Case 7, 20148 | Female, 69 years | Diabetes, recurrent otitis media, heart valve disease | Aortic (native) | Bilateral (LE more affected) | No | Ceftriaxone and levofloxacin | No | No perception of light in LE, perception of light in RE |

| Case 8, 20159 | Male, 48 years | Rheumatic heart disease | Aortic and mitral (native) | Not specified | Liver and spleen abscess | Ceftriaxone and vancomycin penicillin G | Not specified | Cure (residual VA not specified) |

| Case 9, 201810 | Male, 56 years | Diabetes, otitis media | Aortic (native) | Bilateral | No | Ceftriaxone; valve resection with prosthesis implant | Ceftazidime and vancomycin | Perception of light in RE, partial recovery of VA (0.8) in LE |

| Our case | Female, 80 years | Degenerative heart valve disease | Mitral (native) | Bilateral (RE more affected) | No | Piperacillin/tazobactam, levofloxacin, linezolid ceftriaxone, ampicillin | Ceftazidime and vancomycin | Death |

AVB: atrioventricular block; LE: left eye; RE: right eye; VA: visual acuity.

In conclusion, in a patient with bilateral endophthalmitis, an endogenous mechanism secondary to haematogenous spread from an extraocular focus should be considered. On rare occasions, pneumococcal endocarditis could constitute the underlying disease. The poor prognosis in terms of visual sequelae and the life-threatening nature of this disorder, demonstrated by our experience and in the review of the literature, means that a high degree of clinical suspicion is vital, followed by an aggressive diagnostic approach for early instigation of the appropriate systemic and intraocular treatment.

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre library for their help in obtaining the articles included in this literature review.

The affiliation of Julio César Vargas at the time of this article was Internal Medicine Service of the Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain.

Please cite this article as: Fernández-Ruiz M, Vargas JC, Ruiz-Ruigómez M. Endoftalmitis bilateral como forma de presentación de una endocarditis neumocócica. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2019;37:488–490.