The incidence of infective endocarditis of implantable cardioverter defibrillators has increased in recent years, which is similar to the increase in the occurrence of fungal endocarditis. We here report the case of an ICD carrier female patient who presented an infection of the lead by Candida albicans.

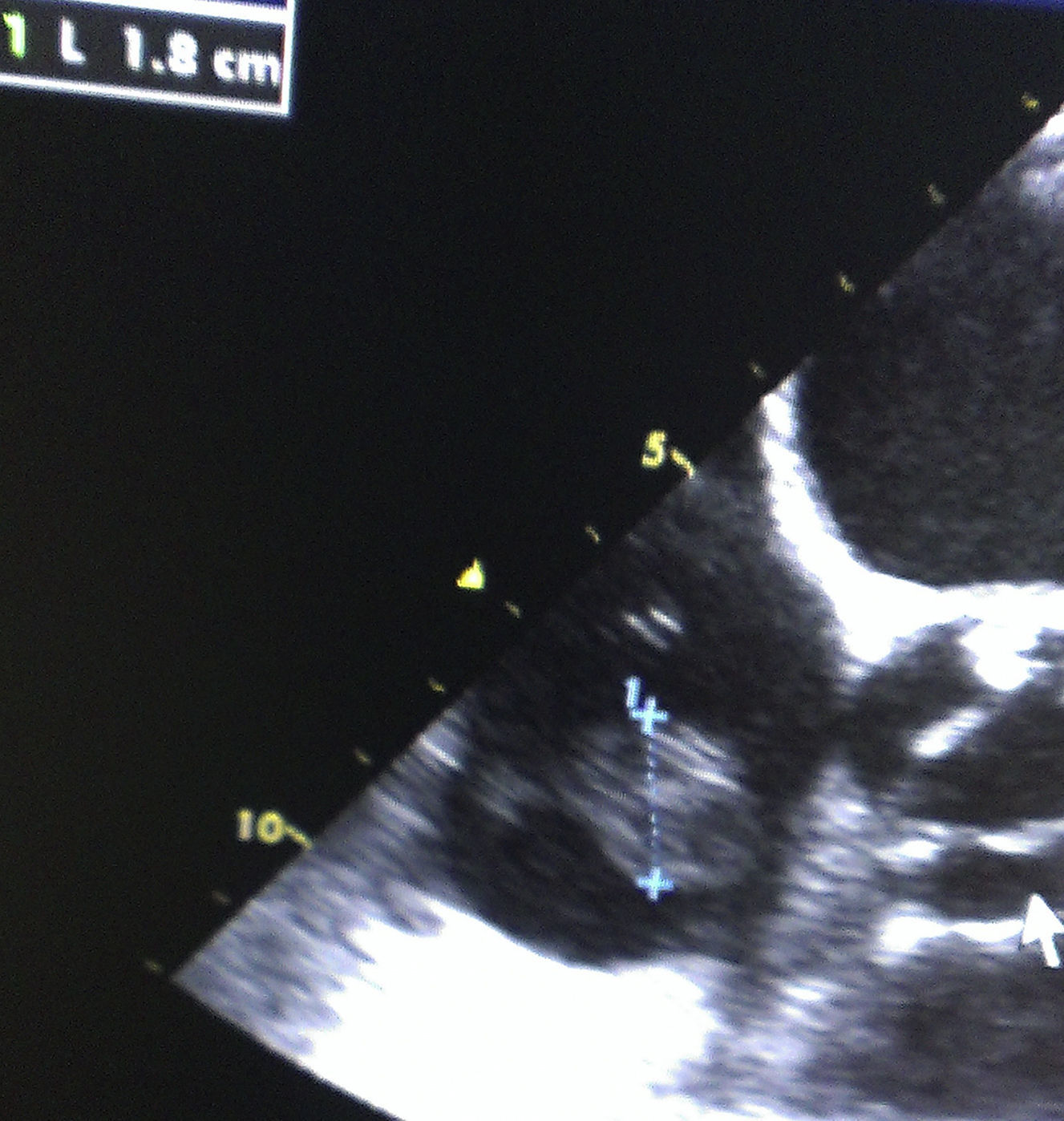

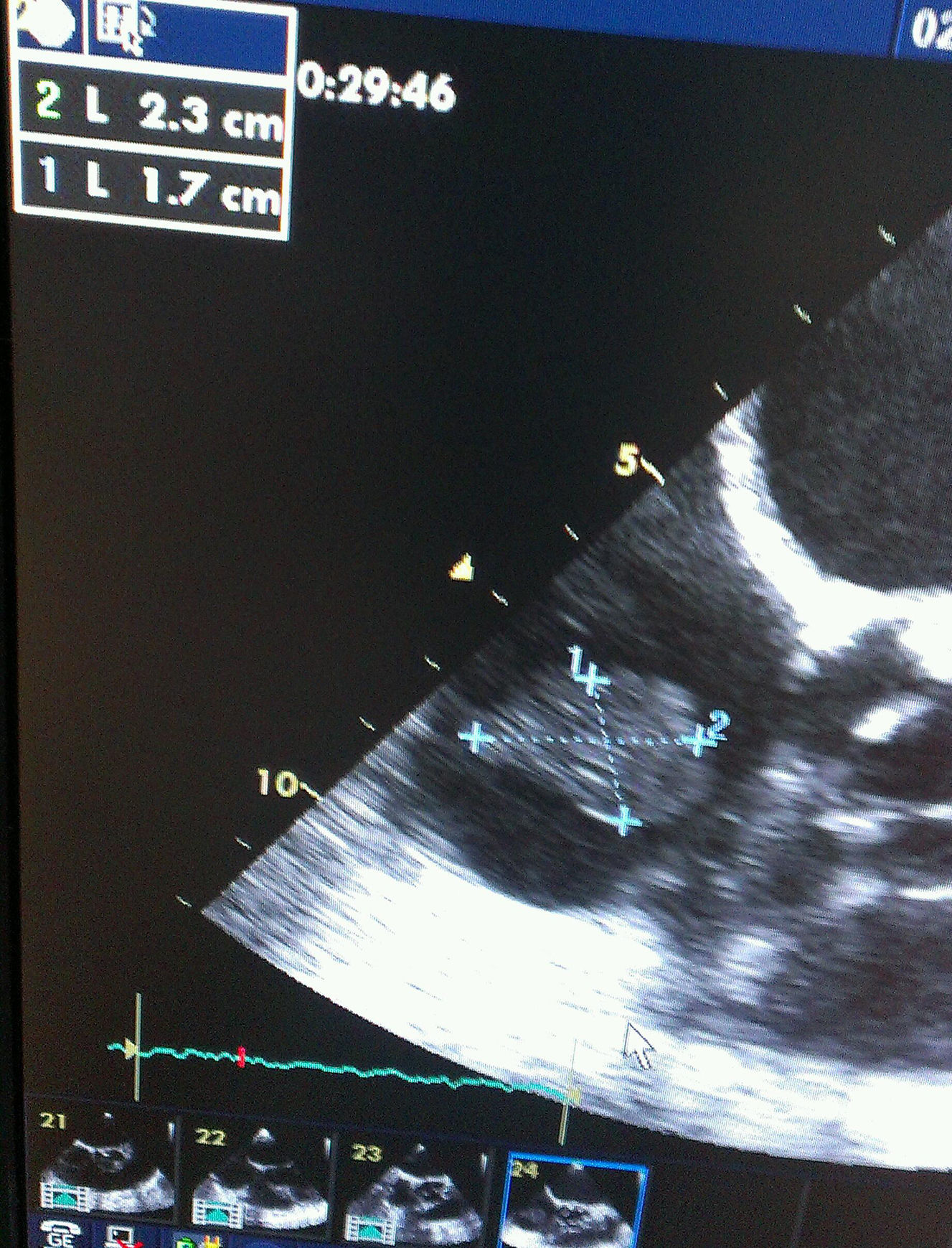

A 65-year-old woman with history of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, chronic renal failure under hemodialysis treatment and dilated myocardiopathy of ischemic origin had an ICD implanted after an episode of cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation in April 2012. In May 2013, she was admitted to the Service of Intensive Care Medicine because of septic shock in relation to a pelvic abscess secondary to perforated diverticular disease. Sigmoidectomy and terminal colostomy was performed, and the patient was discharged from the hospital 6 weeks after surgery. A month later, she was readmitted to the intensive care unit with clinical manifestations of septic shock of unknown origin. Three blood cultures were obtained and in all of which C. albicans was isolated. The patient was treated with liposomal amphotericin B (5mg/kg/day), supportive vasoactive drugs and continuous veno-venous hemofiltration. In transesophageal echocardiography a 23mm size mass was observed attached to ICD electrode (Figs. 1 and 2). Despite the size of the vegetation and given the high surgical risk and multiorgan involvement of the septic process, early removal of the device was considered adequate and assuming the risk of pulmonary embolism. The patient presented various bacteremic febrile episodes over the course of the following weeks but all blood cultures after removal of the ICD were negative. Given the persistence of fever and elevated sepsis-related laboratory parameters, caspofungin was added to treatment with liposomal amphotericin B (loading dose of 70mg i.v.; maintenance 50mg/daily). Repeated echocardiograph studies excluded the presence of endocarditis and/or heart valvular involvement. Bilateral pulmonary septic emboli, which may justify persistent fever, were observed on the thoracic computed tomography (CT) scan. The clinical condition of the patient improved, with hemodynamic stability and decrease of sepsis-related analytical results. Treatment with vasoactive drugs and continuous veno-venous hemofiltration was discontinued. Fours weeks after ICD explantation and after more than 72h with normal temperature, a new device was reimplanted. The patient received the double antifungal treatment for 6 weeks and was discharged home 10 weeks after the admission.

There are a few studies of fungal endocarditis, particularly in the era of the new antifungal agents, such as the latest generation of azoles or echinocandins. Although staphylococci are the pathogens most frequently isolated in ICD-related endocarditis (60–80%), fungal endocarditis accounts for 1–6% reaching up to 10% in some clinical series.1 In carriers of ventricular-assisted devices, Aslam et al.2 reported that fungi were responsible for up to 21% of infections. Fungal endocarditis is predominantly caused by Candida, especially C. albicans followed by Candida glabrata, Candida parapsilosis and Candida tropicalis.3

Risk factors for fungal endocarditis include debilitating diseases, previous use of broad-spectrum antimicrobials, parenteral nutrition and use of intravascular devices, such as catheters, prosthetic heart valves or ICD. Fungal endocarditis is frequently associated with major complications, such as embolisms, in relation to the ability to produce large vegetations, and has a high mortality rate (up to 91% in some series).2

Some aspects of the management of ICD-associated fungal endocarditis are still controversial, and given the paucity of randomized clinical studies, therapeutic decisions in this scenario are challenging for the clinician.

The antifungal regimen recommended by most of the current clinical guidelines includes the use of liposomal amphotericin B (3–5mg/kg/day) or caspofungin (loading dose 70mg; 50mg/day) in association or not with flucytosine (25mg/kg four times a day).4,5 Experimental studies have shown that echinocandins have a higher activity against biofilms as compared to amphotericin B; however, recent reviews of case series studies have not demonstrated differences in mortality between both antifungal agents. Some authors have reported successful results with the combination of liposomal amphotericin B and caspofungin.6 In cases of isolated lead or device infection with positive blood cultures for Candida spp. it has been recommended to maintain treatment for 14 days after blood cultures yielded negative results. In patients with complicated infections (endocardial or valvular involvement, pulmonary embolism or thrombophlebitis), it is recommended to maintain treatment during 4–6 weeks after negativization of blood cultures.4,5,7

Removal of the device is mandatory, and explantation may be performed by the percutaneous route or surgically, although none of the two options are free of risks. Despite the greater experience acquired by professionals in this field and technical advances in the percutaneous explantation procedures, a risk of major complications continues to be present with rates ranging between 0.4% and 5%, being the most feared the pulmonary embolism. At the present time, however, percutaneous extraction is the procedure of choice given the intraoperative and perioperative risks of sternotomy and atriotomy. The 30-day mortality of the percutaneous technique is low (0.1–0.6%), although may increase to 11% in case of large intracardiac vegetations.8,9 Some factors are associated with difficulties in the extraction of the device through the percutaneous approach, such as a length of time from initial implantation over 6 months, a previous unsuccessful attempt of percutaneous removal or spread of the infection to the endocardium. When some of these factors are present, surgical extraction should be evaluated. In relation to the size of the vegetation, satisfactory results with the percutaneous technique even in large vegetations have been reported.10 Surgical removal is performed by means of a sternotomy and atriotomy in association with extracorporeal circulation if needed. The mortality rates range between 0% and 16%, with a lower risk of embolism at the expense of a higher perioperative morbidity.

The optimal time for reimplantation of the device is still unclear. Current recommendations of the American Heart Association (AHS) indicate replacement of the device after 72h of blood cultures negativization in case of infections of the lead, and after 14 days in the presence of valvular infection (evidence IIA, grade C).7 It is necessary to assess the need of reimplantation of the device because in up to one-third of patients, reimplantation is not necessary.9