Neurocysticercosis is a parasitic infection of the central nervous system caused by the cystic larval stage of the tapeworm Taenia solium.1 Endemic areas include Latin America, Southeast Asia, India, Nepal, China, and Africa, where it is a leading cause of acquired epilepsy.1 With increasing globalization and international travel, neurocysticercosis is now being reported in many developed countries.1

We herein report an adult case of cerebral and spinal neurocysticercosis with extensive myocysticercosis, which presented with new-onset convulsive status epilepticus and proximal muscle weakness masquerading clinically as an acquired myopathy.

A 23-year-old male from rural India was brought by his relatives with an acute new-onset generalized tonic–clonic status epilepticus. He was stabilized at the emergency department with intravenous lorazepam (needed a total of 8mg in two separate dosages to abort seizure) and a loading dose of phenytoin (700mg with intravenous normal saline) and shifted to the intensive care unit for close monitoring. His relatives revealed that he complained of progressive generalized weakness, which initially started in the proximal extremities with a visible increase in the bulk of the affected muscles and a bodybuilder-like appearance over the last year associated with easy fatigue and pain. He also complained of persisting headaches with frequent exacerbation and blurred vision for the last two months.

After recovery from the post-ictal state, physical examination revealed that the muscles were firm, tender, and symmetrically hypertrophied in both upper and lower limbs, and weakness, particularly in proximal muscles (MRC 3-/5). He also had multiple soft, non-tender nodules of variable sizes on the forehead and neck.

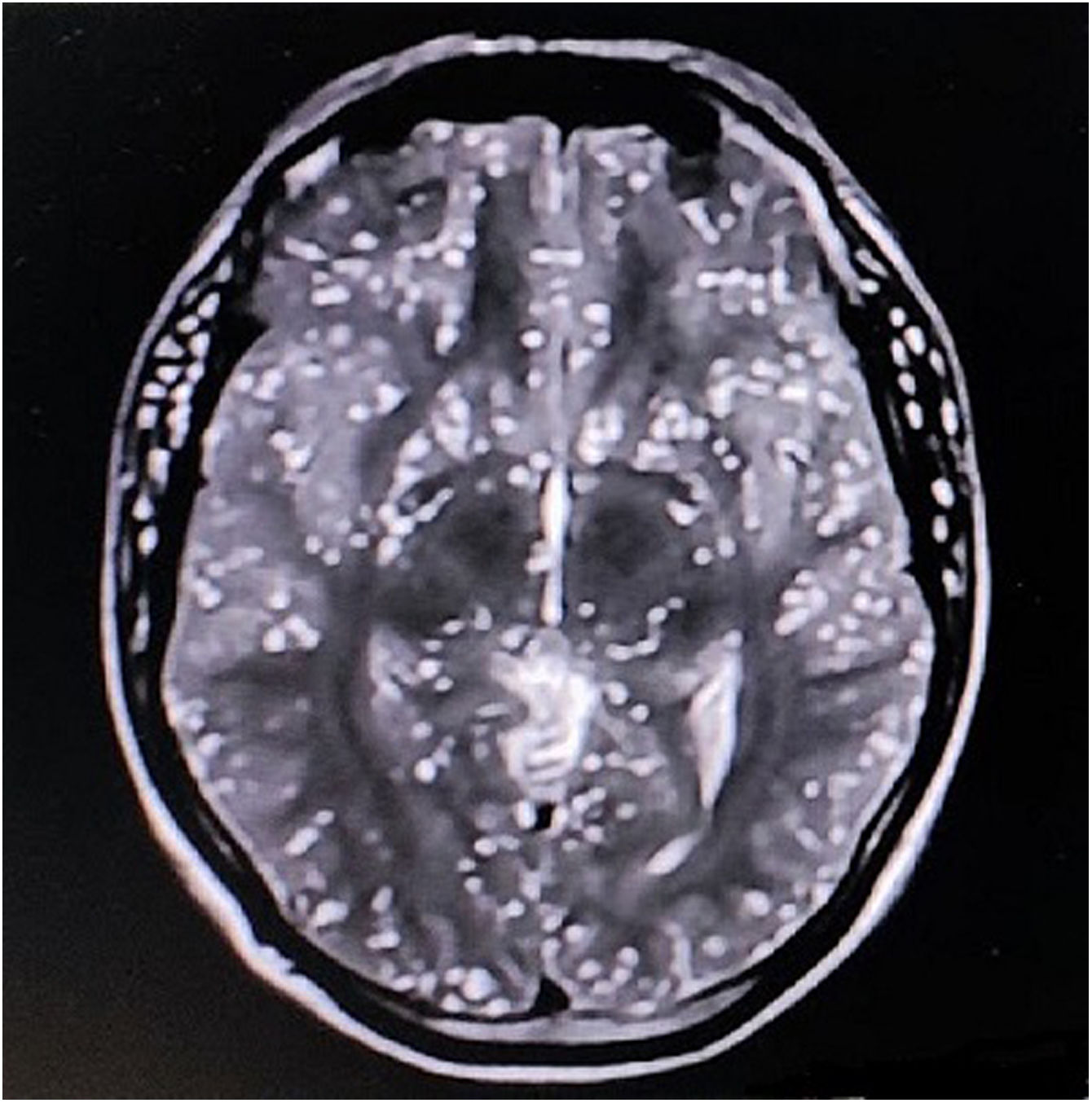

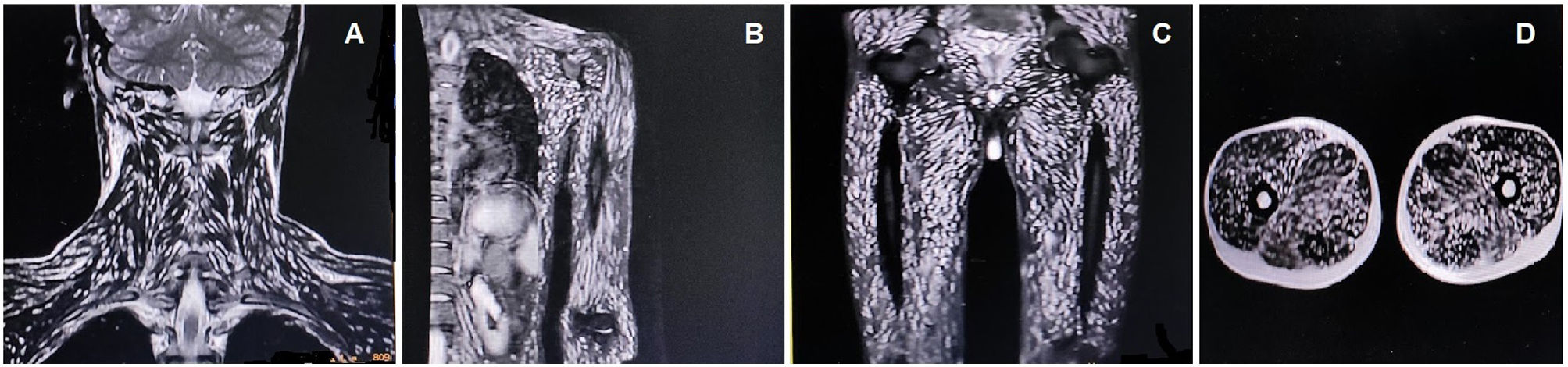

The complete blood cell count revealed mild anemia (10.1g/dL, normal 13.5–17.5g/dL), peripheral eosinophilia (3000eosinophils/μL, normal absolute eosinophil count 30–350eosinophils/μL), and a high erythrocyte sedimentation rate (89mm/h, normal <15mm/h). Serum creatine phosphokinase (978U/L, normal <171U/L) and aldolase (38U/L, normal <7.6U/L) levels were raised. The remaining biochemical parameters were within normal levels. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed the starry sky appearance of neurocysticercosis (Fig. 1). MRI of the neck and limb muscles showed the presence of generalized deposits of cysticercus larvae (Fig. 2). Excision biopsy from a lesion over the left quadriceps muscle was performed, with histopathology revealing cysticercus larvae within the muscle fibers. Diagnosis of neurocysticercosis (including extra-neuralcysticercosis) was finally made. Stool samples from the patient and family members were negative for Taenia solium infestation. MRI screening of the family members was negative for extra-intestinal infestation, too. However, serological tests could not be done due to a lack of specificity/sensitivity and the inadequate laboratory setup required for those tests.

The patient was put on phenytoin (300mg/day in three divided doses) and levetiracetam (2000mg/day in two divided doses) for seizure prevention, together with dexamethasone (24mg/day in three divided doses). Unfortunately, the patient abruptly discontinued antiseizure medication (without supervision) after two months and again came with severe convulsive status epilepticus, and this time, could not be saved despite all possible medical efforts.

Our case highlights the importance of including neurocysticercosis in the differential diagnosis of new-onset convulsive status epilepticus or myopathic pictures, especially in patients from endemic areas.

The decision not to start antiparasitic therapy (albendazole and praziquantel to albendazole) in our patient aligns with our current understanding and recommendations for managing neurocysticercosis, particularly in cases with encephalitis or when there is a risk of exacerbating cerebral edema and brainstem compression (sometimes, this edema can cause blindness if there are lesions near optic nerves).2 Antiparasitic drugs can worsen cerebral edema and potentially trigger new seizures or worsen existing ones.2 In such instances, the priority is stabilizing the patient with antiseizure medications and corticosteroids like dexamethasone to control inflammation.2 This approach aims to manage the acute symptoms and prevent complications associated with increased intracranial pressure and seizure activity. Once the patient is stabilized and the risks of cerebral edema are mitigated, a careful reassessment can be made regarding the timing and safety of introducing anthelmintic therapy.2 Our cautious approach reflects the necessity of balancing the benefits of eradicating the parasite with the immediate risk of precipitating severe complications (i.e., cerebral edema leading to refractory status epilepticus/brainstem compression and visual threat).2

The patient's death after discontinuing antiseizure medication also highlights the critical nature of seizure control in the management of neurocysticercosis. Ensuring patient adherence to prescribed medication regimens is a significant aspect of long-term disease management to prevent such tragic outcomes.

Neurocysticercosis diagnosis depends on multiple factors, including symptoms, imaging with computed tomography and MRI, and serology. MRI provides more detailed images of active parenchymal stages and non-parenchymal disease within the brainstem, subarachnoid, and intraventricular regions and can confirm the diagnosis of neurocysticercosis if a scolex is identified within the cyst (a pathognomonic finding) as well as identify disease outside of the parenchyma.3

The most common presentation of parenchymal neurocysticercosis is focal and brief seizures.1 Convulsive status epilepticus is a rare presentation of all the evolutionary stages of neurocysticercosis.4,5 Perilesional factors like perilesional edema and gliosis have also been implicated in neurocysticercosis-associated epileptogenesis,4,5 but the effects of cystic factors, including lesion load and location, seem not to play a role in the development of epilepsy.

Neurocysticercosis is a multifaceted disease with a broad spectrum of clinical and radiographic features, whose medical management is complex and needs to be individualized. Early recognition of this clinical-parasitic-radiographically setting is essential for achieving a proper treatment to reduce morbidity and mortality. Further studies are needed to elucidate the exact epileptogenic mechanisms in neurocysticercosis.

Ethical statementWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient participating in the study (consent for research). We also confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors contributed significantly to the creation of this manuscript; each fulfilled criterion as established by the ICMJE.

FundingNone declared.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

J. Benito-León is supported by the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA (NINDS #R01 NS39422), the European Commission (grant ICT-2011-287739, NeuroTREMOR), the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (grant RTC-2015-3967-1, NetMD – platform for the tracking of movement disorder), and the Spanish Health Research Agency (grant FIS PI12/01602 and grant FIS PI16/00451).