79-Year-old male patient with a history of moderate palpebral ptosis, undergoing follow-up by ophthalmology since January 2014 due to age-related macular degeneration. Included in an authorised clinical trial on different intravitreal injection (IVI) regimens in the “treat and extend” arm, was receiving monthly IVIs of ranibizumab 0.5mg/0.05ml in the left eye, although the period between them was not extended due to ongoing active age-related macular degeneration.

The IVIs were administered following basic aseptic measures (cap, mask and gloves) in a clean room (not an operating theatre). To disinfect the conjunctiva and surrounding skin, povidone-iodine 5% was applied and left to act for at least 3min. Both the eye speculum and other materials used in the process were sterile. The ranibizumab was in single-dose vials, one per patient, and no sterility control was performed on these vials after each IVI.

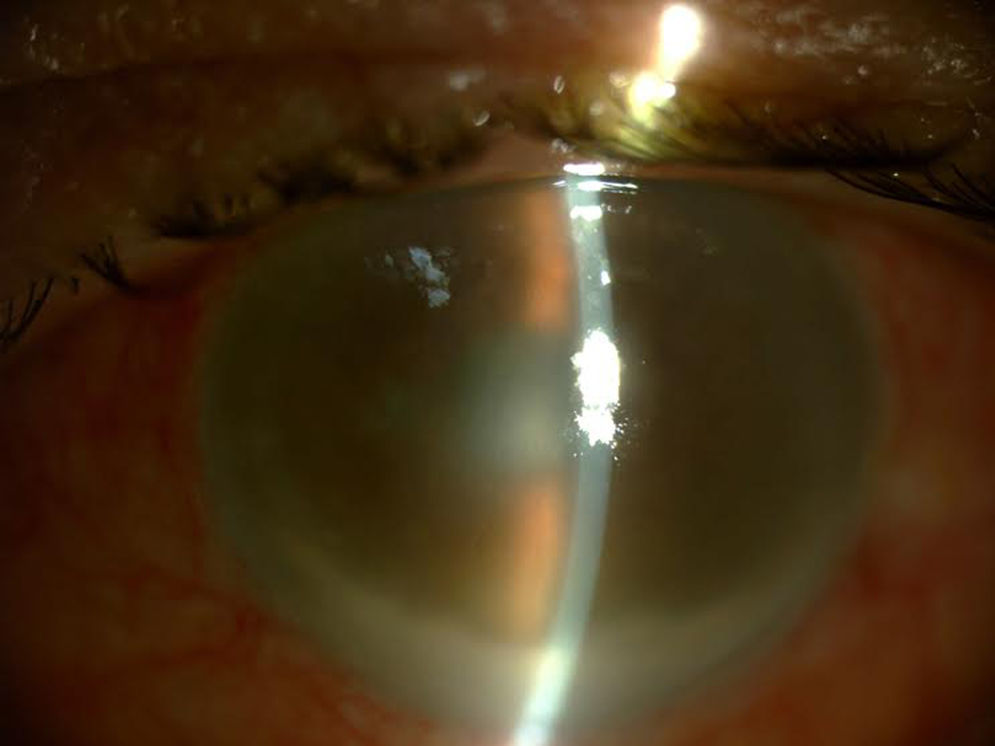

Three days after administering the last IVI of 11 previous injections, the patient went to the Emergency Department presenting symptoms of hyperacute endophthalmitis beginning the day after the procedure, with severe vision loss, inflammation and eye pain (Fig. 1).

Clinical course0.15ml of aqueous humour and 0.4ml of vitreous humour were extracted, which were placed in blood culture bottles and sent to the Microbiology Department.

The samples were incubated in the automated BacT/ALERT® system (bioMérieux) as per routine laboratory practice. 24h later, growth was detected in the vitreous humour, with the Gram stain showing Gram-positive cocci in chains. This was subcultured in chocolate agar, blood agar, Sabouraud agar and anaerobic medium and an α-haemolytic Streptococcus pneumoniae was recovered through sensitivity to optochin and rapid pneumococcal agglutination (Slidex® pneumo-Kit, bioMérieux). Antimicrobial susceptibility tests were performed in a disc and Etest®, following CLSI guidelines, proving sensitive to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, cefotaxime, penicillin, vancomycin, co-trimoxazole, levofloxacin, erythromycin, clindamycin, tetracycline, rifampicin and meropenem. The serotype of this strain was 35F. The aqueous humour culture was negative after 30 days of incubation.

One aliquot of sample was also sent to the University of Valladolid Institute of Applied Ophthalmology for PCR, which reported it as Streptococcus spp.

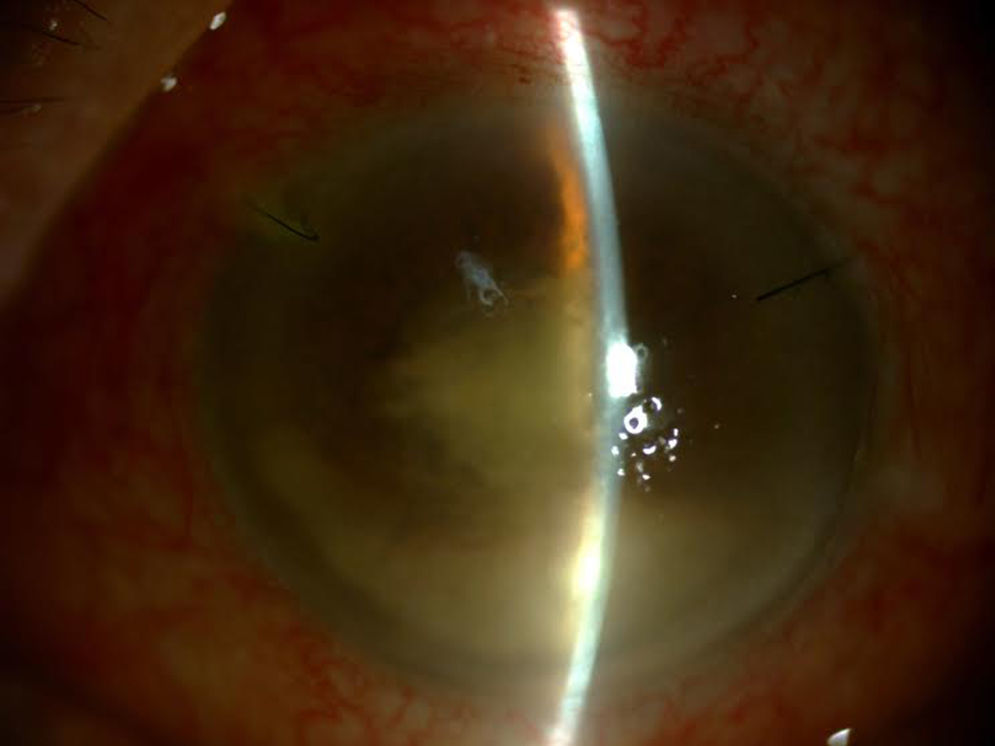

After a diagnostic and therapeutic vitrectomy, doses of intravitreal vancomycin 1mg/0.1ml, ceftazidime 2mg/0.1ml and dexamethasone 4mg/0.1ml were injected, and oral treatment was initiated with moxifloxacin 400mg/day, clarithromycin 500mg/12h and prednisone 40mg in a downward taper, as well as topical moxifloxacin 0.5%, prednisolone acetate 1% and atropine 1% (Fig. 2).

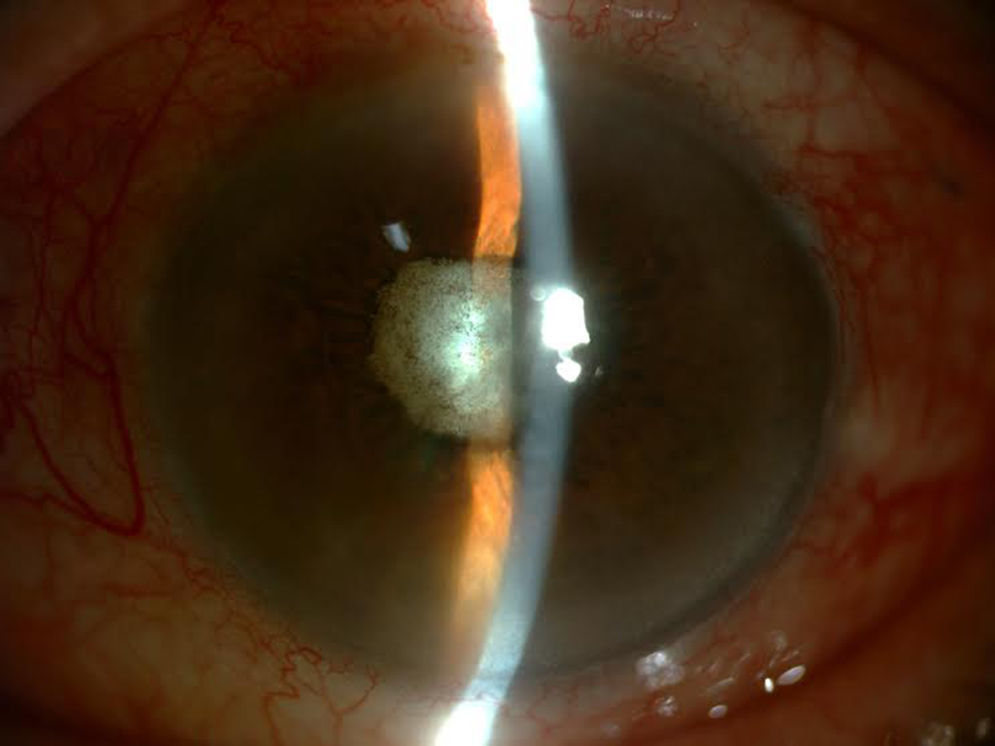

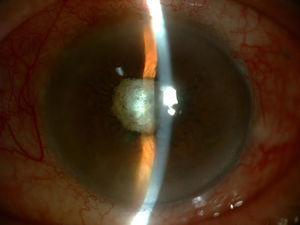

Although a mild initial improvement was observed, the patient's subsequent evolution was negative, despite IVIs of vancomycin 1mg/0.1ml and amikacin 0.4mg/0.1ml being administered on two occasions and the vitreous cavity being considered sterile on presenting negative cultures in subsequent samples. Given that the eye was amaurotic and painful, enucleation was decided upon (Fig. 3).

CommentsEndophthalmitis is the inflammation of intraocular fluids and tissues secondary to an infectious agent. It presents with blurred vision, eye pain, sensitivity to light, conjunctival hyperaemia and hypopyon.1 Despite adequate treatment, it often leads to a total or partial loss of vision. Postoperative endophthalmitis is the most common form (70%) and may be acute (<6 weeks post-surgery) or delayed (>6 weeks).2 Besides surgery, it can also arise as a result of a loss of eyeball integrity, either due to trauma or other procedures, such as IVIs.3,4

Ranibizumab is a humanised monoclonal antibody fragment produced in Escherichia coli cells by recombinant DNA technology indicated in different ophthalmological diseases, such as age-related macular degeneration. Endophthalmitis is an uncommon severe adverse effect (≥1/1000 to <1/100 patients) of ranibizumab.5

It has been published that patients who receive IVIs have a higher risk of presenting streptococcal endophthalmitis as well as having a worse visual prognosis.6 Despite adequate and early treatment, endophthalmitis caused by S. pneumoniae usually has a rapid onset and is associated with a poor visual prognosis.7

S. pneumoniae serotype 35F is poorly understood and has been associated with cases of invasive pneumococcal diseases. Its emergence has taken on greater importance after the introduction of the 13-valent vaccine, in which it is not included. Its increasing frequency and virulence make it a potential candidate for inclusion in future vaccines.8

Thank you to the Instituto de Salud Carlos III National Microbiology Centre for serotyping the stain, and the University of Valladolid Institute of Applied Ophthalmology for the PCR analysis performed.

Please cite this article as: Kohan R, Miguel MA, Cordovés L, Lecuona-Fernández M. Endoftalmitis tras tratamiento intravítreo con ranibizumab. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2017;35:463–464.