Enterovirus D68 (EV-D68) is a virus belonging to species D of the genus Enterovirus within the Picornaviridae family. It was first described in 1962 in California as rhinovirus 87 and cause of paediatric respiratory infections.1 In 2014, a significant epidemic of respiratory infections caused by EV-D68 was reported in the United States, affecting more than 1100 patients, in some cases associated with neurological complications.2 As a result of this situation, a number of different countries, including France, Italy, the Netherlands, Germany and other European countries, began to look for this virus in both paediatric and adult respiratory infections.3,4

In Spain, some isolated cases of community-acquired and hospital-acquired acute respiratory infection associated with EV-D68 have been reported in the adult population and in children.5,6 Because of the distinct lack of information regarding this disease in adults, we decided to analyse the epidemiological characteristics of the 12 cases of acute respiratory infection associated with EV-D68 recently detected.

In December 2017 and January 2018, 1050 respiratory samples from adult patients were processed. Each of them was subjected to real-time commercial PCR (RT-PCR) (Allplex Respiratory Full Panel Assay, Seegene, South Korea) for the detection of respiratory viruses.

During this time, 651 positive samples were detected (62%). These comprised 37 enteroviruses (5.6%), 12 (32.4%) of which were identified as EV-D68 clade A, subclade A1 at the Centro Nacional de Enterovirus [Spanish Enterovirus Centre] in Madrid through RT-nested PCR and sequencing of the 3-VP1 region of the virus.6 These 12 enteroviruses represented 1.8% of the positive samples and 1% of the total analysed.

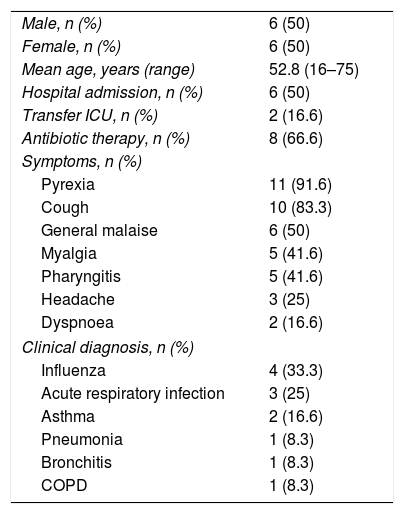

The main clinical and epidemiological characteristics of these patients are shown in Table 1. Most of the respiratory infections were mild or moderate or flu-like; only two patients (16.6%) required admission to the ICU, one as a result of a severe asthma attack and the other a flu-like episode with respiratory distress. The mean age of our patients (52.8 years) was older than that reported in another study (36.7 years).7 In the Meijer et al. study,8 28% of the adult cases were in the 40–59 age group. None of the patients died and all were discharged from hospital without any sequelae of note.

Main characteristics of the 12 adult patients with EV-D68 detected in the respiratory tract.

| Male, n (%) | 6 (50) |

| Female, n (%) | 6 (50) |

| Mean age, years (range) | 52.8 (16–75) |

| Hospital admission, n (%) | 6 (50) |

| Transfer ICU, n (%) | 2 (16.6) |

| Antibiotic therapy, n (%) | 8 (66.6) |

| Symptoms, n (%) | |

| Pyrexia | 11 (91.6) |

| Cough | 10 (83.3) |

| General malaise | 6 (50) |

| Myalgia | 5 (41.6) |

| Pharyngitis | 5 (41.6) |

| Headache | 3 (25) |

| Dyspnoea | 2 (16.6) |

| Clinical diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Influenza | 4 (33.3) |

| Acute respiratory infection | 3 (25) |

| Asthma | 2 (16.6) |

| Pneumonia | 1 (8.3) |

| Bronchitis | 1 (8.3) |

| COPD | 1 (8.3) |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICU: intensive care unit.

We compared our incidence data with those reported by other authors and found that the 21 cases of EV-D68 in adults in the Schuffenecker et al. study4 in France in 2014 only represented 10.6% of all isolates and their clinical characteristics were similar to those in our study. Three of their patients were admitted to the ICU (14.2%) and four (19%) had pneumonia (8.3% in our study). In Germany, in 2013–2014 Böttcher et al.3 found that EV-D68 represented 0.3% of all respiratory samples, but they do not specify to which age groups they belonged. Other studies hardly report any cases in adults: Lu et al.9 detected two cases (22%) of EV-D68 in adults with mild respiratory disease from 2009 to 2012; and Zhang et al.10 only detected one case from 2011 to 2015, representing 18% of all the isolates. The 2015 comparative study of the circulation of EV-D68 in Europe and the United States by Poelman et al.11 confirmed the low prevalence of this virus in Europe and the lower morbidity during the North American outbreak. In Spain in 2014, Gimferrer et al.5 were the first to report two cases (40%) in adults, in a group of five hospitalised patients; neither of them required intensive care.

None of these studies detected severe neurological disorders or flaccid paralysis in adults as are found in children. It is possible that after multiple and continuous infections by different enteroviruses during childhood, the adult population has heterotypic neutralising antibodies which protect them from the severe forms of this infection.7–9 In spite of that, the first reported case of infection by EV-D68 in an adult in the United States was a pregnant woman, suggesting that her pregnancy could have made her more susceptible to the infection.7

From a virology point of view, these 12 cases could be considered as an outbreak as, apart from having been concentrated in a period of about seven weeks, all EV-D68 belonged to clade A, subclade A1 which had circulated before 2014, while in a multicentre study conducted in Spain, all EV-D68 belonged to clade B and were genetically related to those detected in the United States and Canada in 2014.2,6,7

Acute respiratory infections caused by EV-D68 do not appear to have the same morbidity or virulence as the cases in the paediatric population. In spite of this, their incidence should continue to be monitored and, as far as possible, they should be genetically characterised.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Reina J, Cabrerizo M, del Barrio E. Análisis epidemiológico de las infecciones respiratorias agudas causadas por el enterovirus D68 clado A, subclado A1 en la población adulta. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2019;37:487–488.