The initial lesion in mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (MCL) develops in a similar way to that of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL). Usually after the skin lesion has healed, the infection remains dormant for a variable period of time, from weeks to several years. Mucocutaneous involvement frequently starts on the anterior nasal septum mucosa and appears as a small-sized hyperaemic nodule that rapidly evolves to an ulcer. The nasal septum is invaded, perforated and destroyed if no early treatment is started.1

Nearly 3% of the patients diagnosed with CL caused by Leishmania braziliensis will concomitantly or subsequently develop mucosal disease.2 In contrast, L. infantum is not classically associated with MCL. We herein report a case of MCL caused by L. infantum var lombardi in an immunocompetent patient from Spain.

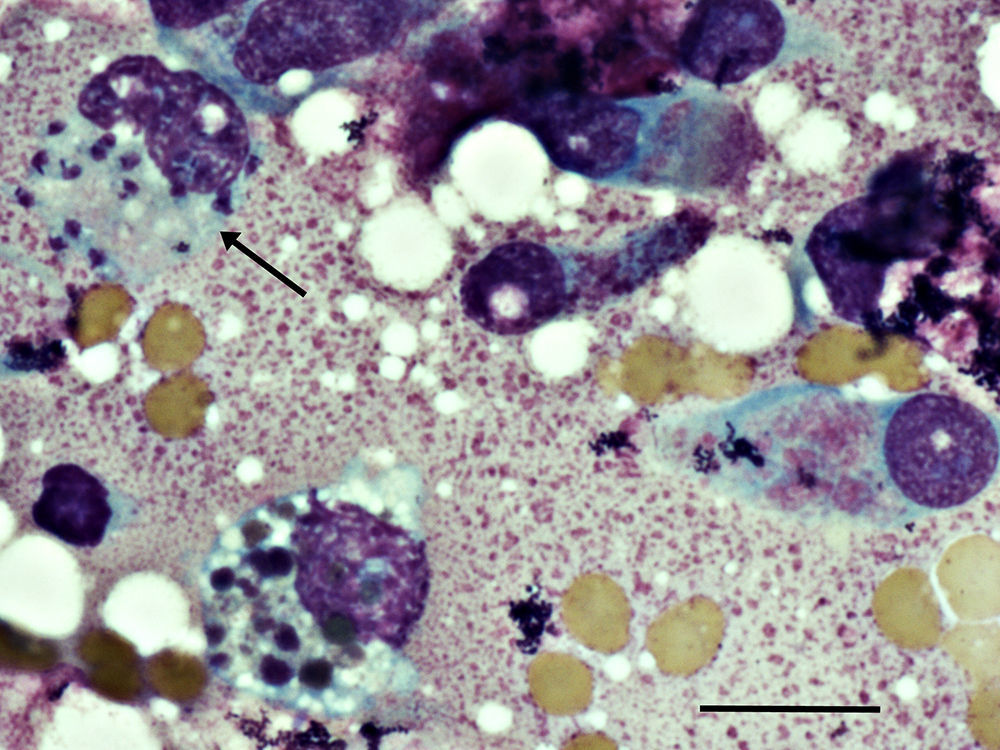

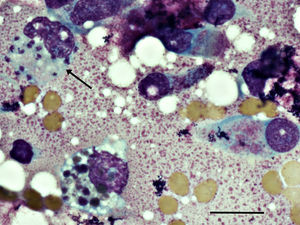

The patient was a 43-year-old healthy man from Madrid – Spain, who was referred to our dermatology department because of a right nasal vestibular induration of three weeks of progression. He also noted a nasal purulent discharge, which caused special discomfort at night for the previous five weeks. He had a history of CL on his left leg during 2011, confirmed by PCR L. infantum var lombardi infection and treated with weekly intralesional meglumine antimoniate with healing of the lesion. On examination, the right vestibule and nasal septum were erythematous and indurated. On the anterior nasal septum mucosa, a nodular lesion without ulceration was observed. Blood test results showed a slight elevation of C-reactive protein, normal CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes count and HIV test was negative. A nasal cytology and a skin biopsy were performed, showing Leishmania amastigote forms (Fig. 1), and were then processed by nested-PCR with a posterior phylogenetic analysis based on the nucleotide sequences to discriminate the Leishmania strain.3L. infantum var lombardi infection was confirmed. The CT scan showed thickening of the right nasal vestibule and the nasal mucosa without cartilage affectation. Abdominal ultrasound and IgG anti-Leishmania were negative. Treatment with intravenous liposomal amphotericin B was started, with a total dose of 18mg/kg. Three months after the initial therapy, the erythema and induration clearly improved, a control biopsy-PCR for Leishmania was negative and the patient's symptoms resolved. After 14 months of follow-up, the patient was asymptomatic.

Photomicrography of a Giemsa–Wright stained nasal cytology showing intrahistiocyte Leishmania amastigotes forms indicated by arrow and epithelial cells of the upper respiratory tract on the right. Slides were examined with a Nikon microscope at 1000× magnification. Scale bar indicates 20nm.

An urban community outbreak of CL and visceral leishmaniasis in the south-west of Madrid had started in July 2009 as reported by Arce et al., with a total of 446 cases up to December 2012; 160 (35.9%) had visceral and 286 (64.1%) exclusively cutaneous forms of the disease, and the cases were confirmed with L. infantum infection.4 The patient had not traveled before to other countries or areas that were highly endemic for Leishmania; therefore, the infection cannot be considered imported. The antecedent of CL in the patient in association with the clinical progression of nasal lesions enhances the diagnosis of MCL, differentiating this to the exclusive mucosal leishmaniasis observed in Europe.5 In the literature reviewed, two immunosuppressed Italian patients with MCL were found, one under multiple immunosuppressive therapy, confirmed with L. infantum infection and the other an HIV positive patient with no molecular confirmation.6,7 The course of the described patient was favorable, and he did not show signs of systemic disease with completed resolution of the infection after treatment with liposomal amphotericin B, an antifungal drug with excellent results in treatment of MCL in Europe.7 This is the first case that demonstrates that L. infantum var lombardi, which is a genotype routinely isolated from Madrid,3 can cause MCL even in immunocompetent patients. It is important to highlight that MCL could be a clinical presentation form of leishmaniasis in travelers returning from Spain, where L. infantum is endemic and should be considered as an infection to initiate a prompt treatment to avoid devastating complications.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest and contributed equally to this article.