Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI)-based regimens are a standard first-line antiretroviral therapy (ART) in Latin-American countries.1 Despite its proven efficacy, the clinical use of first-generation NNRTIs, has been limited by their low genetic barrier and cross-resistance. Rilpivirine (RPV), a new second generation NNRTI, displays in vitro activity extending over other NNRTI-resistant HIV strains.2–4 This drug has a US FDA use in pregnancy rating of category B and it is not recommended the use in pregnancy unless the expected benefit outweighs any potential risks,5 and its final role in pregnancy remains to be determined. To date, there is no information about the rate of RPV resistance-associated mutations (RPV RAMs) in HIV-infected pregnant women (HPW). We aimed to evaluate the prevalence of RPV RAMs in ART-naive and experienced HPW and its impact in the susceptibility profile. During the period March 2008 to August 2012, baseline plasma VL samples from 112 HPW were analyzed. The prevalence of individual RPV RAMs K101E/P, E138A/G/K/Q/R, V179L, Y181C/I/V, H221Y, F227C, M230I/L, Y188L and L100I+K103N combination, was investigated in these samples.6 In patients with, at least, one RPV RAM (including polymorphic mutations, as E138A) the predicted susceptibility was inferred using the Stanford University Drug Resistance Database algorithm (version 7.0). Of 112 HPW, 46.4% (n=52) were ART-naive and 53.6% (n=60, of whom 11 had HIV acquired perinatally) were ART-experienced (all with baseline detectable viral load). The median (interquartile range, IQR) for age, gestational age, VL and CD4 T-cell counts were: 27 years (21–32); 20 weeks (12–26); 9188copies/mL (2827–28,136) and 286μL (197–508), respectively. The predominant HIV-1 subtype was B/F, which was found in 71.2%, followed by B/B (24%). In the experienced group, 65% (n=39) had exposure to first generation NNRTIs (23 to nevirapine, 11 to efavirenz, and 5 to both). None had prior or ongoing exposure to RPV or etravirine (ETR). Evidence of RPV resistance (%, IC95%) was found in 16/112 (14.3%, ±6.4) patients: 5/52 (9.6%, ±8) in naive and 11/60 (18.3%, ±9.7) in experienced HPW. Ten individual RPV RAMs were identified, with an overall prevalence of 4.5% (±3.8) for E138A; 3.6% (±3.4) for E138K; 2.7% (±3) for Y181C; 1.8% (±2.4) for Y188L and H221Y; 0.9% (±1.7) for E138G, E138Q, K101P, V179L and Y181I. The combination L100I+K103N was found in 2/60 (3.3%, ±4.5) experienced HPW, in one case associated with E138K mutation. Prior NNRTI (either efavirenz or nevirapine) use was observed in 91% experienced patients harboring RPV RAMs, with a median (IQR) exposure of 24 (6–115) months. No association with any subtype was found. Individual RPV RAMs profile, ART exposure and predicted RPV susceptibility are shown in Table 1. All naive pregnant women with RPV RAMs had evidence of, at least, reduced susceptibility to RPV while 9/11 (82%) experienced HPW had predicted intermediate or high level resistance. Despite the limited period of time and number of patients, some aspects should be highlighted. In a population of experienced HPW, 18.3% of patients had RPV resistance considering either individual RPV RAMs, L100I+K103N combination or both, which can be mostly attributed to prior exposure to first generation NNRTIs. In this context, a reduction in the susceptibility to the drug was observed in the majority of experienced patients harboring RPV RAMs. Anta et al. recently described that 19.3% genotypes from patients failing NNRTIs are RPV-resistant.7 Considering exclusively NNRTI-experienced HPW in our cohort, 25% should be considered RPV-resistant (data not shown). Of note, none of our patients had exposure to ETR, which shares RPV's resistance profile.4–8 However, the highest burden of RPV resistance was in women infected perinatally (8 of 11 patients) and had been heavily exposed to NNRTI-based ART, with irregular adherence. In this clinical scenery, cross RPV resistance could emerge as a result of long term non-adherence to first generation NNRTIs. Considering the naive patients, these preliminary data show a moderate prevalence of RPV RAMs. Reports of RPV RAMs in naive patients are limited.9 Chueca et al. described an overall 7.7% RPV RAMS in HIV-1 infected patients, being E138A present in 5.5%.10 Such prevalences are lower than those described here. The prevalence of RPV RAMs in naive HPW could be attributed, to cross resistance to first generation NNRTI-selected and, subsequently, transmitted drug-related mutations. As E138A polymorphism is one of the most prevalent RPV RAMs, development of a validated score could be clinically useful. Further research is needed to evaluate if HIV subtype has an influence in RPV resistance. Our study supports routine genotype before prescribing RPV in this population.

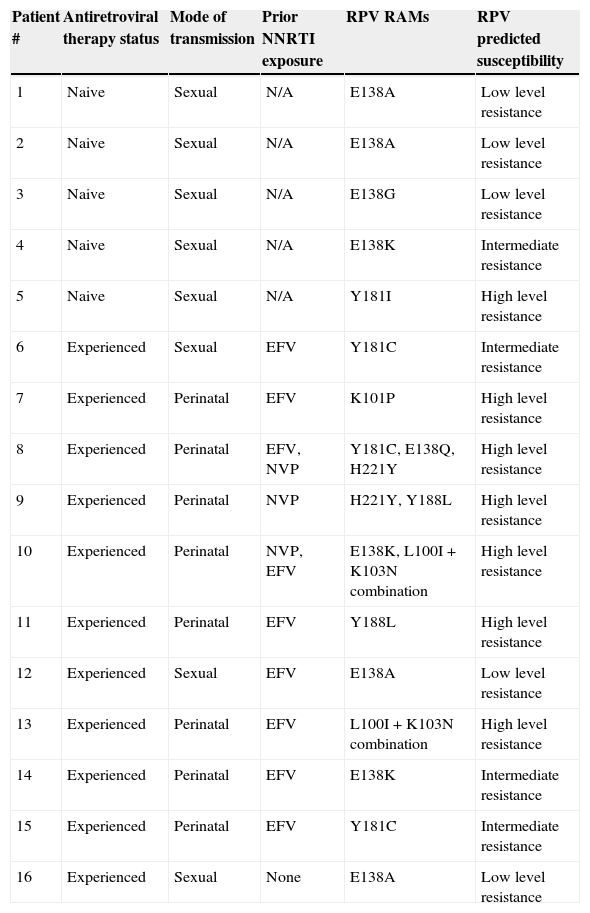

Rilpivirine resistance associated mutations (RPV RAMs) and predicted susceptibility in HIV-infected pregnant women.

| Patient # | Antiretroviral therapy status | Mode of transmission | Prior NNRTI exposure | RPV RAMs | RPV predicted susceptibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Naive | Sexual | N/A | E138A | Low level resistance |

| 2 | Naive | Sexual | N/A | E138A | Low level resistance |

| 3 | Naive | Sexual | N/A | E138G | Low level resistance |

| 4 | Naive | Sexual | N/A | E138K | Intermediate resistance |

| 5 | Naive | Sexual | N/A | Y181I | High level resistance |

| 6 | Experienced | Sexual | EFV | Y181C | Intermediate resistance |

| 7 | Experienced | Perinatal | EFV | K101P | High level resistance |

| 8 | Experienced | Perinatal | EFV, NVP | Y181C, E138Q, H221Y | High level resistance |

| 9 | Experienced | Perinatal | NVP | H221Y, Y188L | High level resistance |

| 10 | Experienced | Perinatal | NVP, EFV | E138K, L100I+K103N combination | High level resistance |

| 11 | Experienced | Perinatal | EFV | Y188L | High level resistance |

| 12 | Experienced | Sexual | EFV | E138A | Low level resistance |

| 13 | Experienced | Perinatal | EFV | L100I+K103N combination | High level resistance |

| 14 | Experienced | Perinatal | EFV | E138K | Intermediate resistance |

| 15 | Experienced | Perinatal | EFV | Y181C | Intermediate resistance |

| 16 | Experienced | Sexual | None | E138A | Low level resistance |

NNRTI: nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; EFV: efavirenz; NVP: nevirapine; N/A: not applicable.

All authors declare no competing interests.

To Silvina Fernandez-Giuliano and Lilia Mammana (Virology Unit, Hospital Francisco J. Muñiz) and Marina Martinez (Neonatology Unit, Hospital Cosme Argerich) for their contribution to the study.

Data from this paper was partially presented at the 7th IAS Conference on HIV Treatment, Pathogenesis and Prevention, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 30 June–3 July 2013 (Abstract TUPE271) and at the 14th European AIDS Conference, Brussels, Belgium, 16–19 October 2013 (Abstract PE 9/8).