Organizing pneumonia (OP) is a rare complication of influenza virus infection but scarce data are available. The recognition of this entity is important because require appropriate treatment.

MethodsWe report two cases and perform a systematic review on PubMed database. Only cases with histological confirmation of OP and influenza virus positive laboratory test were included.

ResultsWe collected 16 patients. Median age was 52 year, 20% of patients were smokers and 43.8% had not any comorbidity. Influenza A virus infection was diagnosed in 75%. Clinical manifestation consisted on a respiratory deterioration with a median time of appearance of 14 days. Radiological pattern observed was ground-glass opacities with consolidations. Survival was observed in 12 patients (75%). All three patients who did not receive steroid treatment died.

ConclusionPhysicians must be aware that patients with influenza infection with a torpid course could be developing OP and prompt corticoid therapy should be instaured.

La neumonía organizada (OP, por sus siglas en inglés) es una complicación poco frecuente de la gripe. El reconocimiento de esta entidad es importante porque requiere un tratamiento adecuado.

MétodosComunicamos 2 casos y realizamos una revisión sistemática en PubMed, incluyendo casos con confirmación histológica de OP y prueba de laboratorio positiva para gripe.

ResultadosSe recogieron 16 pacientes. La edad media fue de 52 años, el 20% eran fumadores y el 43,8% no tenían comorbilidades. El virus de la gripe A se identificó en el 75% de los casos. La presentación clínica consistió en un deterioro respiratorio, con una mediana de aparición de 14 días. El patrón radiológico más común fue opacidades en vidrio esmerilado con consolidaciones. Sobrevivieron 12 pacientes (75%). Los 3 pacientes que no recibieron tratamiento esteroideo murieron.

ConclusiónLos clínicos deben tener en cuenta que los pacientes con gripe con un curso tórpido puedan estar desarrollando una OP.

The influenza virus is a known cause of acute respiratory illness that occurs in epidemics worldwide. The major complications of influenza virus infection (IVI) are secondary bacterial superinfection and viral influenza pneumonia.1 These complications affect especially older patients and those with chronic diseases.2

Organizing pneumonia (OP) is an unusual interstitial lung disease that affects the distal bronchioles and alveoli, it is considered a nonspecific response to a lung injury.3 It can occur associated with connective tissue diseases, drugs, malignancy and bacterial or virus infections.4 Some authors reported that OP might occur as a rare complication after IVI. However, the differential diagnosis between secondary OP and other IVI complications, such as bacterial superinfection, it is difficult. Nevertheless, the diagnosis of secondary OP is important because requires specific therapy.

We report two cases of OP secondary to IVI and, because of the scarce data published about this complication, we carry out a review of published cases in the literature.

Material and methodsWe report two cases of secondary OP diagnosed during the influenza outbreak of 2017–2018. A search on PubMed database was conducted to find other reported cases of secondary OP after IVI. The following keywords were used: “cryptogenic organizing-pneumonia”, “secondary organizing-pneumonia”, “bronchiolitis obliterans organizing-pneumonia;” and “influenza virus”. Only cases with histological confirmation of OP and personal history of IVI were included.

ResultsCase 1A 51-year-old white woman, who was a heavy smoker, was admitted to emergency department complaining of right pleuritic pain, fever, cough and flu-like symptoms. A chest X-ray showed consolidations in lower and medium pulmonary right lobes. Amoxicillin–clavulanic acid was initiated. She was also diagnosed of influenza A and oseltamivir was prescribed. Pneumococcal and Legionella urinary antigen test and blood and sputum culture were negative. Despite treatment, the patient showed a progressive respiratory worsening with new onset left pleuritic pain. At day 12 after admission, a chest computed tomography (CT) revealed consolidations in lower right lobe in resolution, but also appearance of new bilateral consolidations with ground glass opacities in upper pulmonary lobes. Treatment with intravenous methylprednisolone was initiated (dosage 1mg/kg/day). Bronchoscopy was performed, and no virulent pathogens were isolated. Transbronchial biopsy diagnosed OP. Notable clinical improvement after steroid therapy was noticed and the patient was discharged on day 36. After oral prednisone therapy was tapered, disease recurred and she required an increase corticosteroid dosage. After that, the patient evolved correctly.

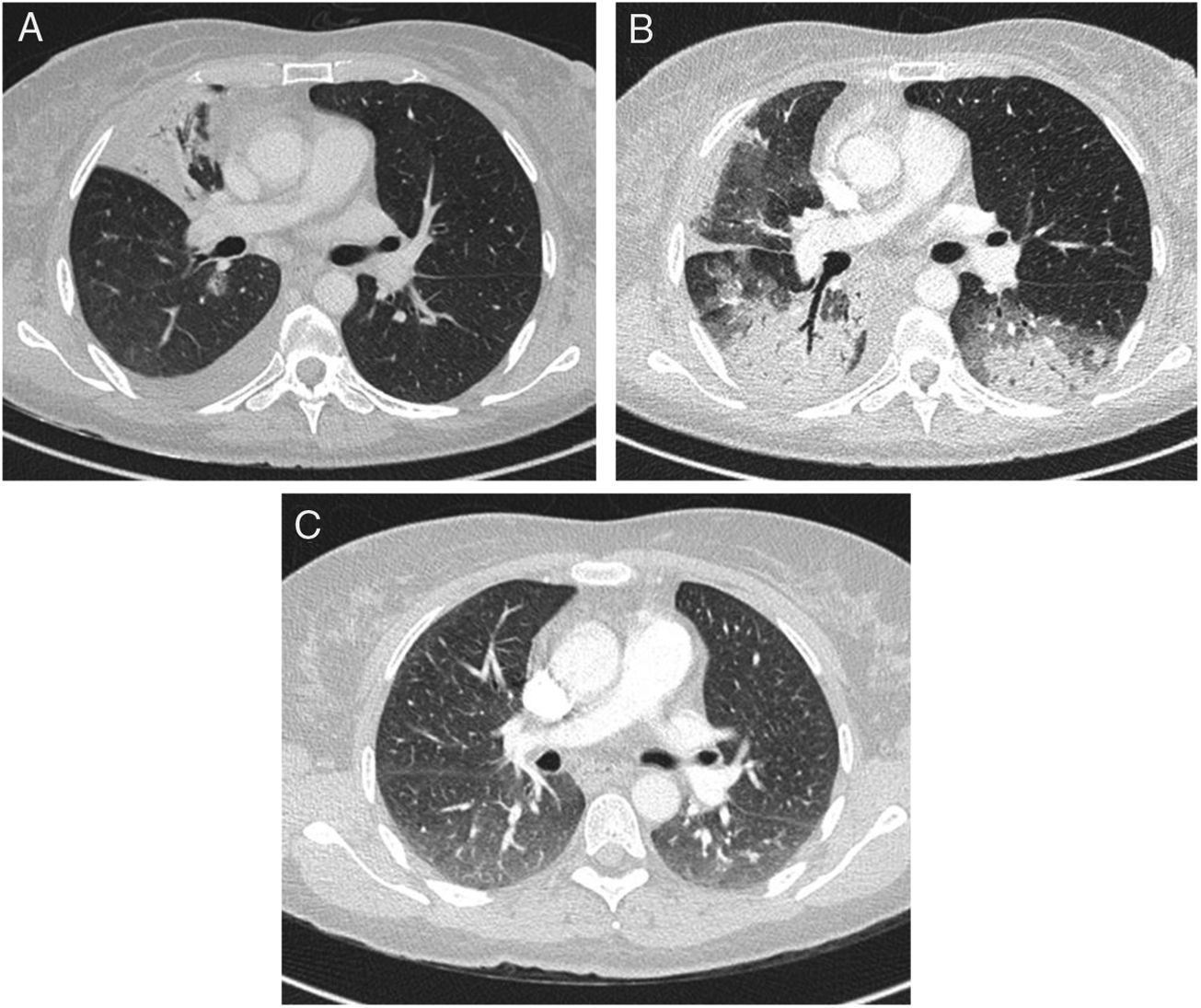

Case 2A 55-year-old white male, who was a smoker, with a history of aortic valve replacement, was admitted to hospital with fever, dyspnea, productive cough and flu-like symptoms. Chest X-ray showed bilateral infiltrates. Amoxicillin–clavulanic acid and azithromycin were initiated. The patient presented progressive deterioration with respiratory failure, requiring endotracheal intubation and admission into Intensive Care Unit. He was diagnosed with influenza A infection. Antimicrobial therapy was changed to cefotaxime plus azithromycin plus oseltamivir. No other pathogens were identified. Two weeks later the patient improved and extubation was possible. 27 days after admission, his pulmonary function deteriorated again. Chest-CT showed extensive ground-glass opacities and bilateral consolidations (Fig. 1). Bronchoscopy and transbronchial lung biopsy was performed. All cultures were negative. Treatment with methylprednisolone was initiated (dose 1mg/kg/day) and a progressive improvement was noticed. Histological results of transbronchial biopsy were compatible with OP. The patient was discharged on day 36 and therapy with oral prednisone was tapered. No recurrence of illness was observed.

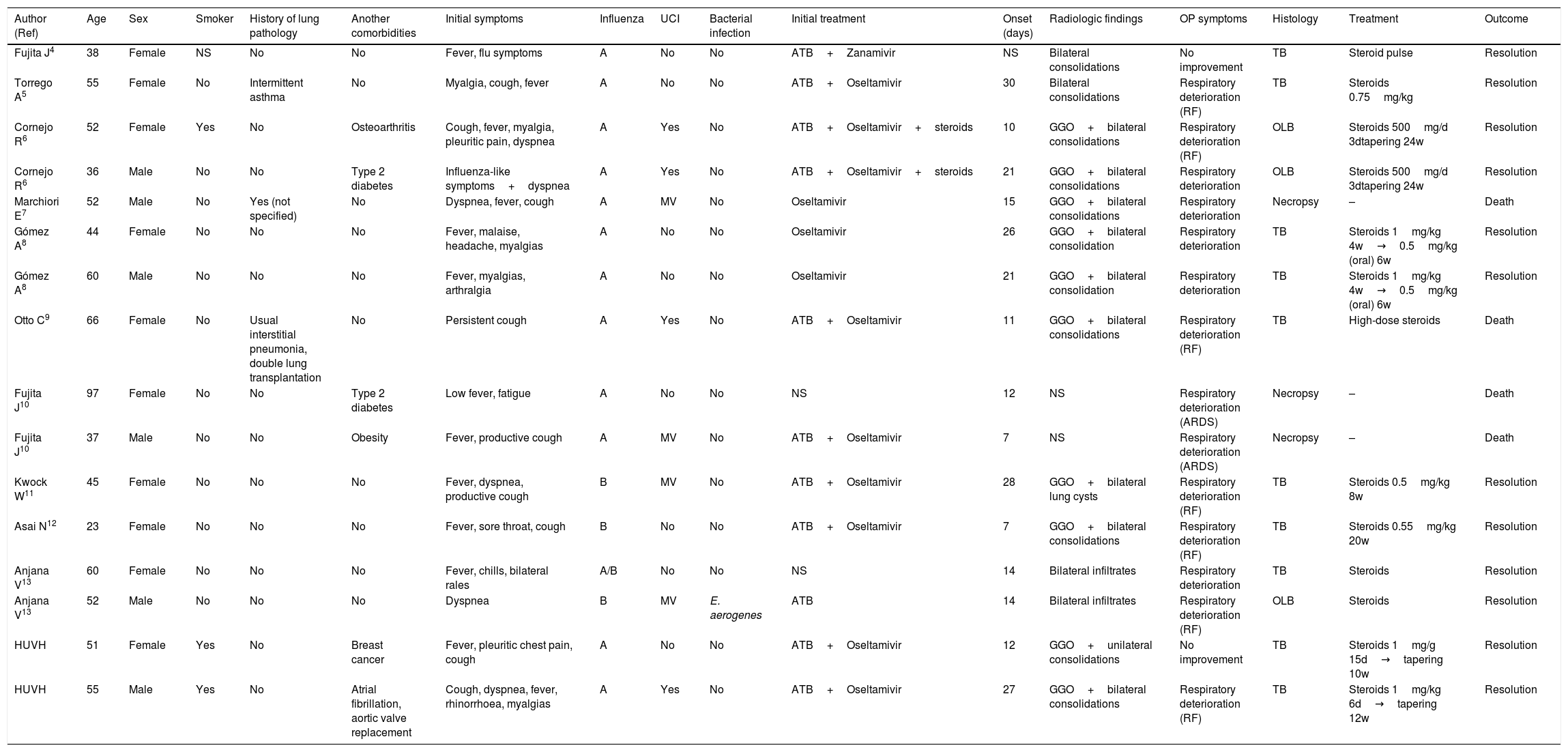

Literature reviewWe identified a 14 cases of OP secondary to IVI which were reported in 10 publications.4–13 Data is summarized in Table 1.

Basal and clinical characteristics of patients with post-influenza organizing pneumonia.

| Author (Ref) | Age | Sex | Smoker | History of lung pathology | Another comorbidities | Initial symptoms | Influenza | UCI | Bacterial infection | Initial treatment | Onset (days) | Radiologic findings | OP symptoms | Histology | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fujita J4 | 38 | Female | NS | No | No | Fever, flu symptoms | A | No | No | ATB+Zanamivir | NS | Bilateral consolidations | No improvement | TB | Steroid pulse | Resolution |

| Torrego A5 | 55 | Female | No | Intermittent asthma | No | Myalgia, cough, fever | A | No | No | ATB+Oseltamivir | 30 | Bilateral consolidations | Respiratory deterioration (RF) | TB | Steroids 0.75mg/kg | Resolution |

| Cornejo R6 | 52 | Female | Yes | No | Osteoarthritis | Cough, fever, myalgia, pleuritic pain, dyspnea | A | Yes | No | ATB+Oseltamivir+steroids | 10 | GGO+bilateral consolidations | Respiratory deterioration (RF) | OLB | Steroids 500mg/d 3dtapering 24w | Resolution |

| Cornejo R6 | 36 | Male | No | No | Type 2 diabetes | Influenza-like symptoms+dyspnea | A | Yes | No | ATB+Oseltamivir+steroids | 21 | GGO+bilateral consolidations | Respiratory deterioration | OLB | Steroids 500mg/d 3dtapering 24w | Resolution |

| Marchiori E7 | 52 | Male | No | Yes (not specified) | No | Dyspnea, fever, cough | A | MV | No | Oseltamivir | 15 | GGO+bilateral consolidations | Respiratory deterioration | Necropsy | – | Death |

| Gómez A8 | 44 | Female | No | No | No | Fever, malaise, headache, myalgias | A | No | No | Oseltamivir | 26 | GGO+bilateral consolidation | Respiratory deterioration | TB | Steroids 1mg/kg 4w→0.5mg/kg (oral) 6w | Resolution |

| Gómez A8 | 60 | Male | No | No | No | Fever, myalgias, arthralgia | A | No | No | Oseltamivir | 21 | GGO+bilateral consolidation | Respiratory deterioration | TB | Steroids 1mg/kg 4w→0.5mg/kg (oral) 6w | Resolution |

| Otto C9 | 66 | Female | No | Usual interstitial pneumonia, double lung transplantation | No | Persistent cough | A | Yes | No | ATB+Oseltamivir | 11 | GGO+bilateral consolidations | Respiratory deterioration (RF) | TB | High-dose steroids | Death |

| Fujita J10 | 97 | Female | No | No | Type 2 diabetes | Low fever, fatigue | A | No | No | NS | 12 | NS | Respiratory deterioration (ARDS) | Necropsy | – | Death |

| Fujita J10 | 37 | Male | No | No | Obesity | Fever, productive cough | A | MV | No | ATB+Oseltamivir | 7 | NS | Respiratory deterioration (ARDS) | Necropsy | – | Death |

| Kwock W11 | 45 | Female | No | No | No | Fever, dyspnea, productive cough | B | MV | No | ATB+Oseltamivir | 28 | GGO+bilateral lung cysts | Respiratory deterioration (RF) | TB | Steroids 0.5mg/kg 8w | Resolution |

| Asai N12 | 23 | Female | No | No | No | Fever, sore throat, cough | B | No | No | ATB+Oseltamivir | 7 | GGO+bilateral consolidations | Respiratory deterioration (RF) | TB | Steroids 0.55mg/kg 20w | Resolution |

| Anjana V13 | 60 | Female | No | No | No | Fever, chills, bilateral rales | A/B | No | No | NS | 14 | Bilateral infiltrates | Respiratory deterioration | TB | Steroids | Resolution |

| Anjana V13 | 52 | Male | No | No | No | Dyspnea | B | MV | E. aerogenes | ATB | 14 | Bilateral infiltrates | Respiratory deterioration (RF) | OLB | Steroids | Resolution |

| HUVH | 51 | Female | Yes | No | Breast cancer | Fever, pleuritic chest pain, cough | A | No | No | ATB+Oseltamivir | 12 | GGO+unilateral consolidations | No improvement | TB | Steroids 1mg/g 15d→tapering 10w | Resolution |

| HUVH | 55 | Male | Yes | No | Atrial fibrillation, aortic valve replacement | Cough, dyspnea, fever, rhinorrhoea, myalgias | A | Yes | No | ATB+Oseltamivir | 27 | GGO+bilateral consolidations | Respiratory deterioration (RF) | TB | Steroids 1mg/kg 6d→tapering 12w | Resolution |

ATB: antibiotic treatment; ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; GGO: ground glass opacities; HUVH; Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron; MV: mechanical ventilation; NS: not specified; OLB: open lung biopsy; RF: respiratory failure; TB: transbronchial biopsy; w: weeks; d: day.

The median age of patients was 52 years (range 25–97 years) and 62.5% were woman. Only 20% were smokers, 25% had lung disease and 56.3% had any other comorbidity. 43.75% of individuals were previously healthy. Influenza A virus was diagnosed in 75% of cases. Clinical manifestations of secondary OP consisted on a paradoxical respiratory deterioration with cough and dyspnea; 43.8% of them progressed to respiratory failure and 12.5% to acute respiratory distress. The median time of appearance OP symptoms/signs was 14 days (range 7–30 days). The most common radiological pattern observed was bilateral, peripheral, ground-glass opacities with consolidations on chest-CT. Almost all patients (81.3%) received steroid treatment, of those 92.3% survived and 7.7% died. All three patients who did not receive steroid treatment died.

DiscussionPost-influenza OP is a rare complication of IVI that has been described in few case reports.4–13 However, the diagnosis of secondary OP is important, because without appropriate treatment could be fatal. In this article we provide some information that could help clinicians to suspect and diagnose this entity.

The major complication of IVI is bacterial superinfection pneumonia, which occurs most frequently in older patients with underlying chronic diseases.14 Nevertheless, secondary OP affect especially healthy young adults. Cases of post-influenza OP reported in the literature presented with a median age of 50 years, and 50% of them had not any relevant comorbidity.

The time of presentation should be also taking into consideration. Whereas influenza pneumonia is diagnosed in days 4–5 after the first symptoms appear and bacterial superinfection in days 7–10,4,15 in 2/3 of cases reported, secondary OP occurred after two weeks of influenza infection manifestations appears. Moreover, in about a quarter of cases OP occurred later, 4 weeks after the diagnosis of flu.

The typical clinical presentation of OP consists on a subacute paradoxical pulmonary function deterioration with non-productive cough, dyspnea that can progress to respiratory failure and occasionally, fever.

One of the most relevant findings that can lead to the diagnosis of post-influenza OP are the images at the chest-CT. At imaging, the most typical pattern consists on multiple and bilateral ground glass opacities and pulmonary consolidations, with peribronchovascular and subpleural distribution.

Secondary OP remains a diagnosis of exclusion. When the most common diagnoses have been ruled out, more invasive diagnostic procedures should be conducted if the patient's condition allows it. Transbronchial biopsy with anatomopathological examination of the samples obtained gives the definitive diagnosis, although that is only possible in a minority of patients. Histologically, Marchiori et al. correlated pathologic findings with CT images. They found that the areas of consolidation corresponded to alveoli filled with edema fluid, inflammatory exudate or hemorrhage.7 They also found that the ground-glass pattern reflected the alveolar septal thickening. In contrast, lung tissue from individuals affected of IVI showed as predominant features diffuse alveolar damage and alveolar hemorrhage.16

Corticosteroids are the cornerstone in the management of this entity. All post-influenza OP cases were resolved after corticosteroid therapy, except for the patient with personal history of lung transplantation.9 All three patients who did not received corticosteroids died.6,9 In one of the studies found, a patient started steroid therapy after 84 days of initial symptoms and despite improvement, she suffered from secondary extensive lung fibrosis and residual dyspnea.11 So, early corticosteroid treatment should be considered in cases of suspicions OP thus seems to improve outcome and avoid further complications. Most clinicians use moderate doses for prolonged periods of at least 3–6 months, but relapse is common when corticosteroids dosage is tapered off.

In conclusion, physicians must be aware that some patients with IVI, either influenza A or B, and a torpid clinical course could be developing OP. The presentation in healthy young adults 2–4 weeks after the onset of the symptoms, and a new appearance of consolidations or/and ground glass opacities on CT may suggest this diagnosis. In those scenarios, corticoesteroids are the treatment of choice. This entity should be considered in the list of possible complications for patients with influenza who do not improve or have a clinical deterioration.1

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interests.