There is little information regarding peripheral facial palsy (PFP) as a complication of varicella. We describe 2 adults who developed varicella-related PFP, in 1 case as a part of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), and review all reported cases of this condition.

MethodsMEDLINE search.

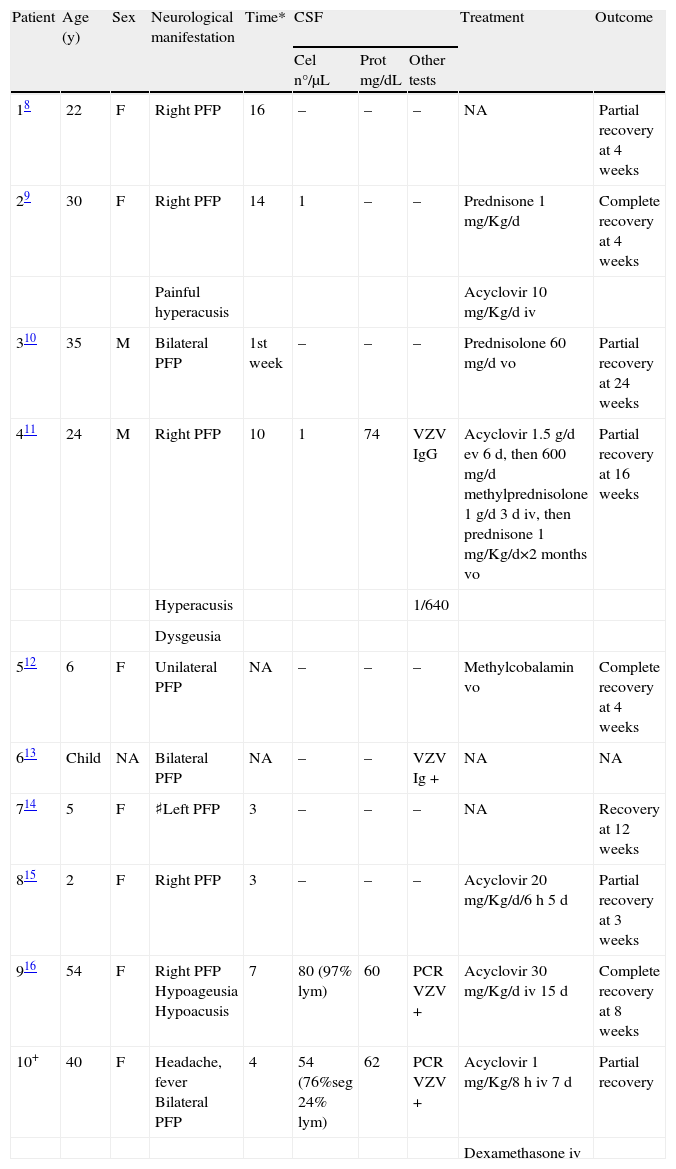

ResultsA total of 10 cases of isolated varicella-associated PFP have been reported. PFP was diagnosed 3 to 16 days after the onset of skin manifestations. Four (40%) patients developed bilateral PFP. Two patients had varicella meningitis; both were PCR-positive for varicella-zoster virus (VZV) in CSF. CSF IgG antibodies against VZV were demonstrated in 2 other patients. One patient had slight CSF albumino-cytological dissociation. Five patients were treated with acyclovir, and 3 of them also received corticosteroids. Most patients showed a favorable course, with partial or complete recovery of PFP.

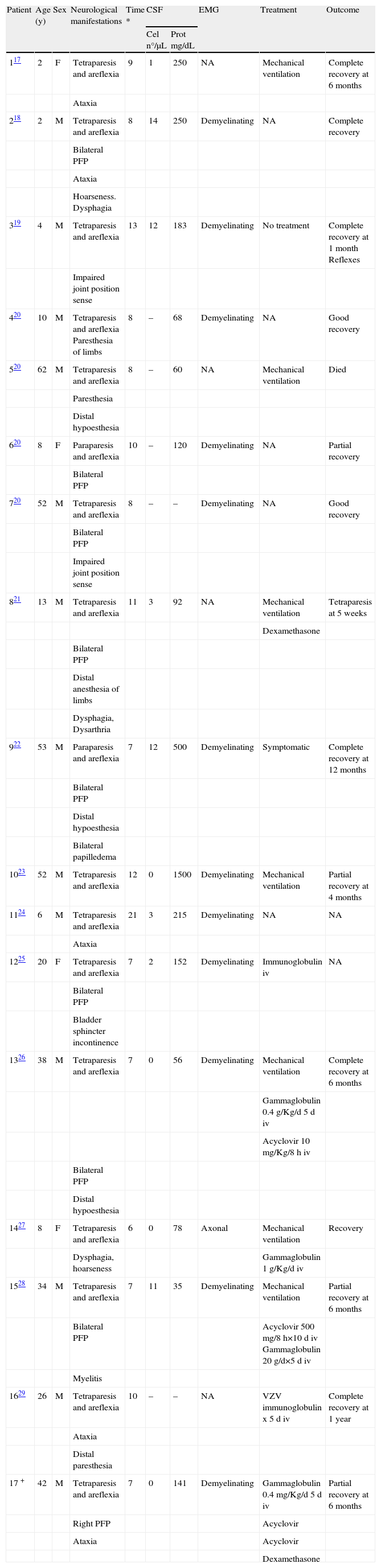

In addition, 17 patients with GBS after the onset of varicella were reviewed. Mean time to the development of GBS after varicella onset was 9.3 days, and 9 patients had PFP as a part of the neurologic picture. Seven patients (41%) developed respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. Six patients received treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin, and all of them showed optimal evolution. One patient died.

ConclusionsIsolated PFP and GBS are rare peripheral nerve complications after varicella. Treatment should be individualized for each case, depending on the severity of the condition and the clinical evolution.

Existe escasa información referente a la parálisis facial periférica (PFP) como complicación posvaricela. En este artículo se describen 2 casos, uno de ellos en relación al Sd. de Guillain-Barré (SGB) y se revisa lo descrito anteriormente en la literatura.

MétodosRevisión en MEDLINE.

ResultadosSe han descrito 10 casos de PFP relacionada con varicela. La PFP se ha diagnosticado de 3 a 16 días después de la aparición de las lesiones cutáneas. Cuatro (40%) pacientes desarrollaron PFP bilateral. Dos pacientes tuvieron meningitis por varicela, ambos tenían PCR de virus varicella-zoster positivo en LCR. Se documentó la presencia de anticuerpos Ig G en LCR frente VZV en otros 2 pacientes. Un paciente tenía disociación albúmino-citológica en LCR. Cinco pacientes fueron tratados con aciclovir y 3, concomitantemente, con corticoides. La mayoría de pacientes mostró una buena evolución, con una resolución total o parcial de la PFP. A su vez, analizamos 17 pacientes con pacientes SGB después de varicela. El tiempo medio de desarrollo el SGB fue de 9,3 días. Nueve pacientes presentaron PFP en relación con el episodio de SGB. Siete (41%) pacientes presentaron insuficiencia respiratoria grave que precisó de ventilación mecánica. Seis pacientes recibieron tratamiento con inmunoglobulinas, todos ellos con una buena evolución. Un paciente falleció.

ConclusionesLa PFP y el SGB son complicaciones poco frecuentes de después de la varicela. El tratamiento se debe individualizar en cada caso, dependiendo de la gravedad y la evolución clínica.

Varicella results from primary infection by varicella-zoster virus (VZV). A typical exanthematous vesicular rash, low-grade fever, and malaise are the main clinical manifestations. The most common extracutaneous site of involvement is the central nervous system.1 The neurologic abnormalities usually manifest as acute cerebellar ataxia and/or encephalitis.2,3 However, VZV can cause many neurologic complications, including peripheral neuropathies.4,5

Information about varicella-associated peripheral facial palsy (PFP) is scarce. We have recently treated 2 adults who developed varicella-related PFP, one of them as a part of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), and the other as an isolated form in the context of meningitis. Isolated PFP following varicella is not mentioned in the more prestigious medical textbooks.1,6 These cases prompted us to review the literature to obtain better knowledge of the relationship between varicella and PFP, as well as varicella and GBS.

Case reportsCase 1A previously healthy 40-year-old woman was admitted on April 2006 for headache and fever that had developed 5 days after the onset of varicella. On examination, axillary temperature was 38.5°C, and the characteristic skin lesions of resolving varicella were apparent. The remaining physical findings and neurologic examination were normal. Three days after admission, bilateral PFP developed, with no other abnormalities on neurological examination. Cytochemical analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples showed 54 white blood cells/μL (24% lymphocytes and 76% neutrophils), 62mg/dL protein, 2.8mg/dL glucose, and a CSF/serum glucose ratio of 0.52. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of VZV in CSF was positive. The patient received intravenous acyclovir at 10mg/kg every 8 hours. Electromyography (EMG) disclosed severe bilateral axonal damage. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed hyperintensity of various cranial nerves, particularly the seventh cranial nerve. Intravenous dexamethasone 8mg/d was added. Overall, the patient received 14 days of acyclovir and 19 days of dexamethasone (tapering dose). The patient presented gradual improvement of symptoms starting on the third day after admission (ie, first day of acyclovir treatment). At six months of follow-up, the patient had slight PFP on the right side and no other sequelae. The diagnosis was meningitis due to VZV.

Case 2A previously healthy 42-year-old man was admitted in July 2006 because of progressive weakness of all four limbs, numbness, and ataxia, which developed 7 days after the onset of varicella. His past medical history was unremarkable. On examination, axillary temperature was 37.2°C, and multiple skin lesions consistent with varicella were observed. Neurologic examination disclosed weakness predominating in the legs, ataxia, global areflexia, and right-sided PFP. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis showed no cells, 141mg/dL protein, XX mg/dL glucose, and a CSF/serum glucose ratio of 0.6. Computed tomography (CT) and MRI of the brain were normal. EMG findings were consistent with demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy. The patient was treated with intravenous acyclovir, 10mg/kg every 8 hours for 14 days, dexamethasone 16mg/d tapering doses for a total of 10 days, and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg), 0.4mg/kg every 24 hours for 5 days. At 6 months of follow-up, the neurologic examination showed slight PFP on the right side, with no other abnormalities.

Literature review methodsWe conducted a MEDLINE (National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD) search with the subject headings “peripheral facial palsy”, “chickenpox”, “varicella”, and “varicella-zoster virus” to identify case reports of PFP associated with varicella published from 1980 to January 2008. We limited our search to the English, French and Spanish literature. All cases of varicella-related PFP or GBS were reviewed. The inclusion criteria were varicella, defined as a history of consistent clinical manifestations in the presence of typical vesicular skin lesions; PFP, defined on the basis of clinical manifestations, with weakness in facial muscles, including the orbicular and frontal musculatures; and GBS, defined according to the Asbury criteria.7

ResultsThe demographic and clinical characteristics of all reported patients with isolated varicella-related PFP are summarized in Table 1, and the data of all patients with varicella-related GBS are shown in Table 2.

Isolated Peripheral Facial Palsy and Varicella

| Patient | Age (y) | Sex | Neurological manifestation | Time* | CSF | Treatment | Outcome | ||

| Cel n°/μL | Prot mg/dL | Other tests | |||||||

| 18 | 22 | F | Right PFP | 16 | – | – | – | NA | Partial recovery at 4 weeks |

| 29 | 30 | F | Right PFP | 14 | 1 | – | – | Prednisone 1mg/Kg/d | Complete recovery at 4 weeks |

| Painful hyperacusis | Acyclovir 10mg/Kg/d iv | ||||||||

| 310 | 35 | M | Bilateral PFP | 1st week | – | – | – | Prednisolone 60mg/d vo | Partial recovery at 24 weeks |

| 411 | 24 | M | Right PFP | 10 | 1 | 74 | VZV IgG | Acyclovir 1.5g/d ev 6d, then 600mg/d methylprednisolone 1g/d 3d iv, then prednisone 1mg/Kg/d×2 months vo | Partial recovery at 16 weeks |

| Hyperacusis | 1/640 | ||||||||

| Dysgeusia | |||||||||

| 512 | 6 | F | Unilateral PFP | NA | – | – | – | Methylcobalamin vo | Complete recovery at 4 weeks |

| 613 | Child | NA | Bilateral PFP | NA | – | – | VZV Ig + | NA | NA |

| 714 | 5 | F | ♯Left PFP | 3 | – | – | – | NA | Recovery at 12 weeks |

| 815 | 2 | F | Right PFP | 3 | – | – | – | Acyclovir 20mg/Kg/d/6h 5d | Partial recovery at 3 weeks |

| 916 | 54 | F | Right PFP Hypoageusia Hypoacusis | 7 | 80 (97% lym) | 60 | PCR VZV + | Acyclovir 30mg/Kg/d iv 15d | Complete recovery at 8 weeks |

| 10+ | 40 | F | Headache, fever Bilateral PFP | 4 | 54 (76%seg 24% lym) | 62 | PCR VZV + | Acyclovir 1mg/Kg/8h iv 7d | Partial recovery |

| Dexamethasone iv | |||||||||

NA=not available; *Days after onset of skin lesions; ♯Right PFP was detected 7 days before onset of skin lesions; +Case reported by authors of current article.

Guillain-Barré Syndrome and Varicella

| Patient | Age (y) | Sex | Neurological manifestations | Time * | CSF | EMG | Treatment | Outcome | |

| Cel n°/μL | Prot mg/dL | ||||||||

| 117 | 2 | F | Tetraparesis and areflexia | 9 | 1 | 250 | NA | Mechanical ventilation | Complete recovery at 6 months |

| Ataxia | |||||||||

| 218 | 2 | M | Tetraparesis and areflexia | 8 | 14 | 250 | Demyelinating | NA | Complete recovery |

| Bilateral PFP | |||||||||

| Ataxia | |||||||||

| Hoarseness. Dysphagia | |||||||||

| 319 | 4 | M | Tetraparesis and areflexia | 13 | 12 | 183 | Demyelinating | No treatment | Complete recovery at 1 month Reflexes |

| Impaired joint position sense | |||||||||

| 420 | 10 | M | Tetraparesis and areflexia Paresthesia of limbs | 8 | – | 68 | Demyelinating | NA | Good recovery |

| 520 | 62 | M | Tetraparesis and areflexia | 8 | – | 60 | NA | Mechanical ventilation | Died |

| Paresthesia | |||||||||

| Distal hypoesthesia | |||||||||

| 620 | 8 | F | Paraparesis and areflexia | 10 | – | 120 | Demyelinating | NA | Partial recovery |

| Bilateral PFP | |||||||||

| 720 | 52 | M | Tetraparesis and areflexia | 8 | – | – | Demyelinating | NA | Good recovery |

| Bilateral PFP | |||||||||

| Impaired joint position sense | |||||||||

| 821 | 13 | M | Tetraparesis and areflexia | 11 | 3 | 92 | NA | Mechanical ventilation | Tetraparesis at 5 weeks |

| Dexamethasone | |||||||||

| Bilateral PFP | |||||||||

| Distal anesthesia of limbs | |||||||||

| Dysphagia, Dysarthria | |||||||||

| 922 | 53 | M | Paraparesis and areflexia | 7 | 12 | 500 | Demyelinating | Symptomatic | Complete recovery at 12 months |

| Bilateral PFP | |||||||||

| Distal hypoesthesia | |||||||||

| Bilateral papilledema | |||||||||

| 1023 | 52 | M | Tetraparesis and areflexia | 12 | 0 | 1500 | Demyelinating | Mechanical ventilation | Partial recovery at 4 months |

| 1124 | 6 | M | Tetraparesis and areflexia | 21 | 3 | 215 | Demyelinating | NA | NA |

| Ataxia | |||||||||

| 1225 | 20 | F | Tetraparesis and areflexia | 7 | 2 | 152 | Demyelinating | Immunoglobulin iv | NA |

| Bilateral PFP | |||||||||

| Bladder sphincter incontinence | |||||||||

| 1326 | 38 | M | Tetraparesis and areflexia | 7 | 0 | 56 | Demyelinating | Mechanical ventilation | Complete recovery at 6 months |

| Gammaglobulin 0.4g/Kg/d 5d iv | |||||||||

| Acyclovir 10mg/Kg/8h iv | |||||||||

| Bilateral PFP | |||||||||

| Distal hypoesthesia | |||||||||

| 1427 | 8 | F | Tetraparesis and areflexia | 6 | 0 | 78 | Axonal | Mechanical ventilation | Recovery |

| Dysphagia, hoarseness | Gammaglobulin 1g/Kg/d iv | ||||||||

| 1528 | 34 | M | Tetraparesis and areflexia | 7 | 11 | 35 | Demyelinating | Mechanical ventilation | Partial recovery at 6 months |

| Bilateral PFP | Acyclovir 500mg/8h×10d iv Gammaglobulin 20g/d×5d iv | ||||||||

| Myelitis | |||||||||

| 1629 | 26 | M | Tetraparesis and areflexia | 10 | – | – | NA | VZV immunoglobulin x 5d iv | Complete recovery at 1 year |

| Ataxia | |||||||||

| Distal paresthesia | |||||||||

| 17 + | 42 | M | Tetraparesis and areflexia | 7 | 0 | 141 | Demyelinating | Gammaglobulin 0.4mg/Kg/d 5d iv | Partial recovery at 6 months |

| Right PFP | Acyclovir | ||||||||

| Ataxia | Acyclovir | ||||||||

| Dexamethasone | |||||||||

NA=Not available; *Days after onset of skin lesions; +Case reported by authors of current article.

A total of 10 cases of isolated varicella-associated PFP have been reported. The patients were 6 adults and 4 children, and the median age was 24 (range 2–54). PFP was diagnosed 3 to 16 days after the onset of skin manifestations in the 8 cases in whom this information was reported. Four (40%) patients developed bilateral PFP. One of these patients (n° 7, Table 2) presented right-sided PFP 7 days before the onset of skin manifestations and left-sided PFP 3 days after. CSF samples were obtained in 5 cases. Two patients had varicella meningitis and both were PCR-positive for VZV. CSF IgG antibodies against VZV were demonstrated in 2 other patients. One patient had slight CSF albumino-cytological dissociation. Five patients were treated with acyclovir, and 3 of them also received corticosteroids. One patient received corticosteroids alone. The 9 patients whose outcomes were reported showed a favorable course with partial or complete recovery of PFP.

Seventeen patients, 9 adults (52%) and 8 children (48%), with GBS after varicella onset were reviewed. Median age was 20 years (range 2-62). Nine (52%) patients had PFP as a part of the clinical manifestations of GBS, and 8 (88%) of them were affected bilaterally. The time to development of GBS was 6 to 21 days after the onset of varicella, with a mean of 9.3 days. Nine (52%) patients developed GBS on either the seventh or eighth day after varicella onset. Seven patients (41%), 4 adults and 3 children, developed respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. Autoantibody to ganglioside GM1 was determined in 2 patients (n° 13 and n° 14, Table 1). One of them, a patient with demyelinating GBS, had negative autoantibody results and the other, a patient with axonal GBS, had positive results. Four patients were tested for VZV antibodies in CSF, and only one tested positive. In addition, 2 patients were tested for VZV antigen, which was positive in one.

Six patients received treatment with IVIg, and all of them showed optimal evolution. Two patients had the worst outcomes: one died, and the other had severe, irreversible neurologic damage. Neither of these patients had received IVIg treatment.

DiscussionThere is little published information about varicella-associated PFP. We describe 2 cases, one of them as a part of GBS, and the other as an isolated form in the context of meningitis, and extensively review the literature. Taking into account that most cases of varicella occur in children, the relative risk of experiencing such complications is much higher in adults than in children.

Peripheral facial palsy related to varicella is extremely uncommon. The median age of patients with varicella and isolated PFP was much lower than the reported age for PFP due to any cause (40 years),30 probably because of the epidemiology of varicella. Acyclovir and corticosteroids were the treatments most often used. The outcome of patients with isolated varicella-related PFP did not present any particularities compared to those with PFP associated with other causes.31

The pathogenesis of isolated PFP is not completely understood. Some cases have been attributed to ischemia,32,33 but this mechanism should not be relevant in our cohort of young patients. In our opinion, two different pathways may explain the relationship between varicella and isolated PFP. The first would correspond to a direct nerve lesion due to the virus, itself, or to meningeal inflammation in the course of varicella meningitis. Similar pathogenic mechanisms have been associated with another virus causing isolated PFP.34 The second mechanism would consist of an immunologically mediated inflammatory response. This pathway could resemble or correspond to local or general forms of GBS. In this setting, we suggest that some cases of PFP after varicella, especially bilateral PFP, should be regarded as possible mono-symptomatic forms of GBS. Lumbar puncture is rarely performed in these patients and there is little information about CSF status. Our literature search retrieved one report of a patient with isolated PFP who presented albumin-cytologic dissociation, which would be consistent with this pathogenic mechanism.

The time between varicella onset and development of PFP is the only clinical parameter that can raise suspicions of GBS in patients presenting isolated PFP after varicella, since no cases of GBS have been documented before the sixth day of onset of skin lesions. In a review of the literature dealing with GBS associated with infectious agents, no cases of GBS were found to occur before the sixth day of the first manifestation of the infectious disease.35 Additional tests, such as CSF analysis, and EMG study should be considered in this population. PCR for VZV and determination of antibodies against VZV in CSF could be useful, not only in patients with a history of varicella, but also in any case of GBS of unknown etiology, since some cases of primary VZV infection course without skin lesions.

Guillain-Barré syndrome is an acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy clinically characterized by limb weakness and areflexia. According to the literature, PFP occurs in 50% of patients with GBS, and respiratory failure in 30%.6 Our review shows that the clinical manifestations of GBS associated with varicella are similar to those of GBS related to other etiologies. The association between GBS and varicella is rare. GBS is the prototype of post-infectious autoimmune diseases, and it has been reported to occur after Campylobacter jejuni infection.36 Following the model proposed for other infectious agents, such as Campylobacter or Mycoplasma, a phenomenon of cross-reactivity between lipo-oligosaccharides of the virus and epitopes on axolemma and/or on Schwann cells could explain the pathogenesis of GBS after varicella.36 Immunopathological studies suggest that different targets of immune attack could be the reason for the different GBS subtypes,37 currently classified as acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy, acute motor-sensory axonal neuropathy, acute motor axonal neuropathy, acute sensory neuropathy, and acute panautonomic neuropathy.

One-quarter to one-third of patients with GBS have high serum titers of antiganglioside antibodies, and this association is stronger for axonal variants of GBS than for demyelinating forms.38 In our review, autoantibodies to gangliosides were determined in 2 cases, with positive testing in the patient with an axonal variant, and negative results in the patient with a demyelinating form. Formes frustes of GBS are sometimes encountered, with various combinations of ophthalmoplegia, facial palsy, bulbar palsy, and sensory neuropathy.37 The presence of autoantibodies with different targets and, consequently, different clinical manifestations, supports the possibility that some cases of PFP (unilateral or bilateral) could represent mono-symptomatic forms of GBS. Unfortunately, antiganglioside titers were not determined in any of the reported cases of isolated PFP.

In summary, isolated PFP and GBS should be regarded as uncommon complications of varicella. Strict evaluation of isolated PFP to rule out mono-symptomatic forms of GBS should be recommended in this population, particularly in bilateral PFP. Further studies should be done to establish the need for specific treatment for these patients. IVIg treatment can be considered for patients with bilateral varicella-related PFP.

The authors are members of the Spanish Network for Infectious Diseases Research (REIP RD06/0008/0022).

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this study.