Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a common diagnosis in the emergency department1 that continues to be a significant cause of both morbidity and mortality; it is especially serious among the elderly and chronically ill. Much of the cost of the process is due to hospital admissions.2–4 Patients admitted for pneumonia cost 8 times more than those who receive ambulatory treatment.4 Outpatient-treated CAP cases belong to a subgroup marked by age and tend to be young people with high tolerance to symptoms. Nevertheless, mortality due to pneumonia is high in young people admitted to hospital.

Here we report our findings in a series of patients with pneumonia treated at home, cared for and re-evaluated in the Emergency Department of the University Hospital of Salamanca (Spain). We designed a retrospective and descriptive study. Initially, the subjects included 96 randomly selected patients but 14 were lost during the course of the study. Of the 82 remaining patients (mean age 49 years, 54% men), we evaluated the following inclusion criteria: a diagnosis of pneumonia based on the usual clinical picture and X-ray criteria5 in the Emergency Service, outpatient treatment, over 16 years old (age range 16–89 years [24% over the age of 65]) and reappraised at 14 days in the same Department. Data were collected during the year 2009, according to a protocol.6 We measured the following variables: age, sex, comorbidity, the CURB-65 and Fine indices, signs and symptoms, antigenurias, serologies, routine analyses, outcome and antibiotic treatment. The decision to use ambulatory treatment was based on the current guidelines.5

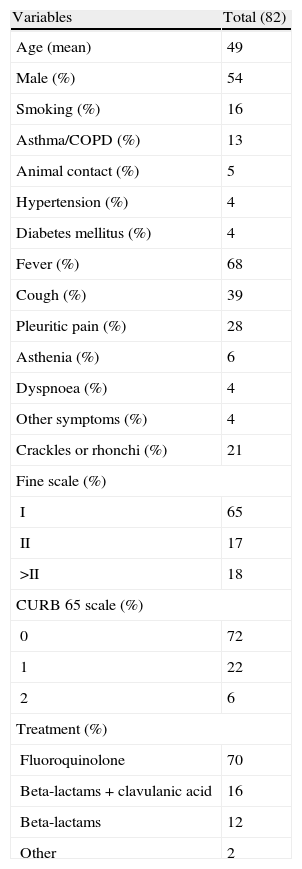

The results relating to the patient history, signs or symptoms, severity scales and treatment are shown in Table 1. Systolic blood pressure was normal in all cases. More than half (57%) had a temperature higher than 37.5°C, and 16% had a heart rate greater than 100 beats per minute or a pulse of less than 60. Oxygen saturation was less than 91% in 3% of patients, 4% were diabetic and 4% had dyspnoea (Table 1), although the glycaemic alterations and the dyspnoea, despite their clinical importance, were not entered in the scales used. The patients with a doubtful prognosis were subjected to further tests or spent more hours under observation. Of the tests performed, antigenuria was positive in 16%: 7 for Streptococcus pneumoniae and 1 for Legionella pneumophila. The serology was suggestive of disease in 26%: 6 for Mycoplasma pneumoniae, 5 for Chlamydia pneumoniae, 3 for Coxiella burnetii and 2 for L. pneumophila. Of all cases, the bacterium responsible was detected in 29%. A sputum sample was only collected in one patient. Gas analysis was performed in 17% of the patients and routine laboratory tests were carried out on all patients, with no relevant anomalies being observed except those mentioned in previous studies (i.e. leukocytosis).

General characteristics of study patients.

| Variables | Total (82) |

| Age (mean) | 49 |

| Male (%) | 54 |

| Smoking (%) | 16 |

| Asthma/COPD (%) | 13 |

| Animal contact (%) | 5 |

| Hypertension (%) | 4 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 4 |

| Fever (%) | 68 |

| Cough (%) | 39 |

| Pleuritic pain (%) | 28 |

| Asthenia (%) | 6 |

| Dyspnoea (%) | 4 |

| Other symptoms (%) | 4 |

| Crackles or rhonchi (%) | 21 |

| Fine scale (%) | |

| I | 65 |

| II | 17 |

| >II | 18 |

| CURB 65 scale (%) | |

| 0 | 72 |

| 1 | 22 |

| 2 | 6 |

| Treatment (%) | |

| Fluoroquinolone | 70 |

| Beta-lactams+clavulanic acid | 16 |

| Beta-lactams | 12 |

| Other | 2 |

As regards treatment, quinolones were used in 68% and beta-lactams in 29%. None of the patients died, but 2 were referred for hospital consultation due to their slow progress.

In our series, the highlights were the optimal outcome of the processes, in agreement with the mild degrees observed in the CURB-65 and Fine scales. Calbo et al. found similar results in their study.7 The typical patient in our series was a young man consulting for fever, cough and expectoration, pleuritic pain and crackles upon auscultation, with a positive antigenuria for S. pneumoniae, and treated with levofloxacin.8 A visit to the hospital after diagnosis was deemed appropriate to verify adequate patient progress after the antibiotherapy treatment, taking advantage of this visit to perform microbiological studies. The aetiology of the pneumonia was similar to other series, the lack of isolated microorganisms being striking.4 The organisms most frequently identified were S. pneumoniae and M. pneumoniae. Rationalization of the decision over patient admittance is an important target in the treatment of pneumonia.9 Thus, prognostic tools –severity scales or prognosis of mortality– able to corroborate our clinical judgment of pneumonia, and that will eventually become a legal part of the clinical history of our patients are necessary. Individuals monitored in an outpatient regiment should be monitored from the hospital, even if only by phone contact.10