Escherichia coli is responsible for most febrile urinary tract infections (FUTI) in men the majority of which are acute prostatitis (AP).1 Fluoroquinolones (FQ) achieve high prostatic concentrations and are considered the first choice in patients with AP.2E. coli is becoming increasingly resistant to FQ limiting its empirical use.3 Given the lack of new antimicrobials it is necessary to reevaluate already existing agents.

Fosfomycin, a bactericidal antibiotic that targets peptidoglycan formation, is active against most E. coli causing FUTI, including extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing E. coli (ESBL-EC) strains.4 Fosfomycin trometamol achieves reasonable intraprostatic concentrations and has been used in the treatment of chronic prostatitis caused by multidrug-resistant bacteria.5 We aimed to assess the prevalence, trends and risk factors associated to fosfomycin resistance (FR) in E. coli from males with a community FUTI.

An ambispective cross-sectional study was performed at a primary care hospital. Data were recorded retrospectively from January 2008 to October 2009 and prospectively from then to December 2015. FUTI was defined as an armpit temperature ≥38°C together with UTI symptoms. When urinary symptoms were absent, diagnosis was accepted if no other infections were found. Variables reviewed included: age, dementia, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney or heart failure, cirrhosis, neoplastic or lung disease, use of immunosuppressive agents, the Charlson score, any antibiotic intake in the previous 30 days, prior UTI and existence of urinary abnormalities. A healthcare-associated FUTI was considered in case of: hospitalization in the previous 90 days; residence in a long term care facility; outpatient care, therapy, or invasive urinary tract procedures, 30 days before the FUTI and presence of an indwelling urethral catheter. Urine samples were obtained from midstream urine or from urinary catheters and cultured on MacConkey agar. Positive urine cultures were defined by bacterial growth ≥103CFU/mL. Identification of E. coli was performed by biochemical methods. Antimicrobial susceptibility was tested by agar diffusion (CLSI criteria). Intermediate and resistant strains were grouped together.

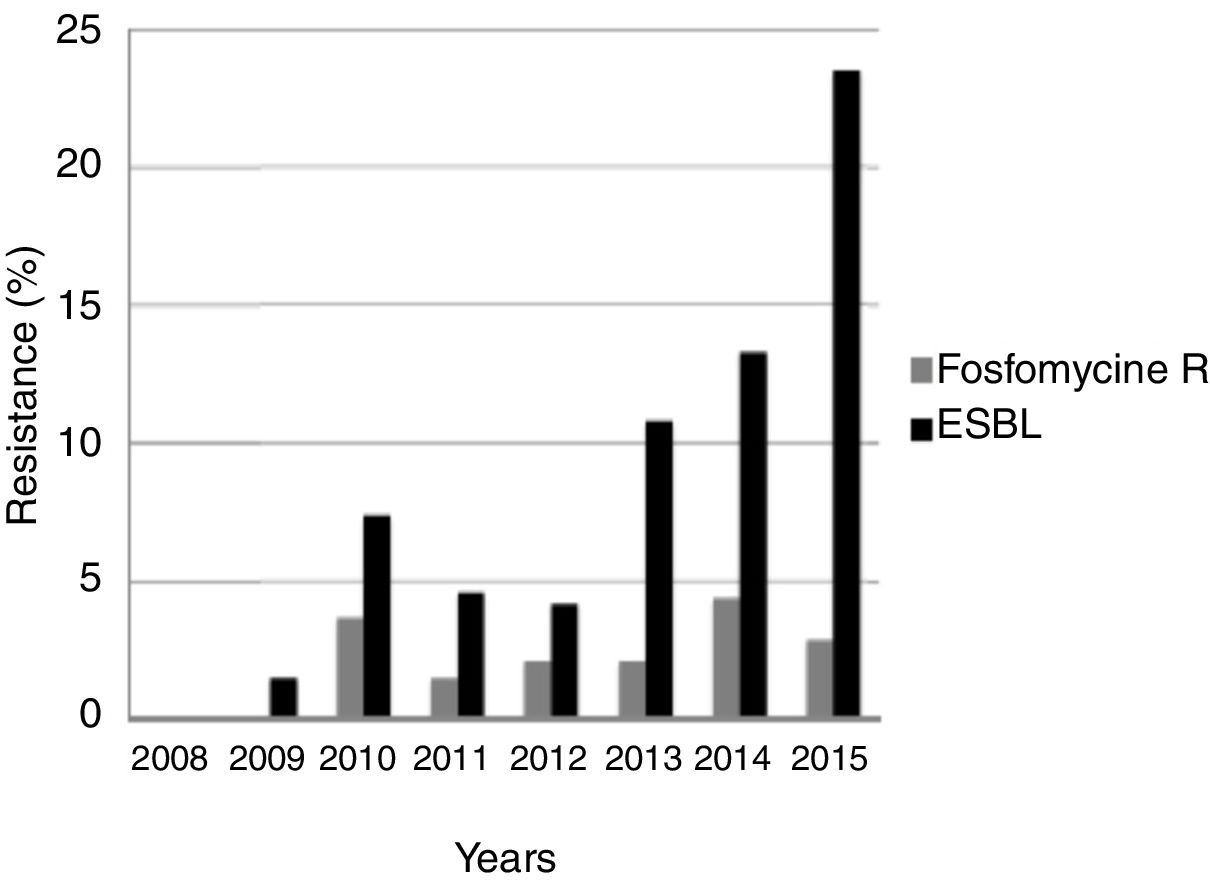

The study included 385 males with a community FUTI due to E. coli. Eight (2.1%) isolates were FR and 377 (97.9%) fosfomycin susceptible (FS). Resistance to FQ (p=0.006), amoxicillin–clavulanate (p=0.01), cefuroxime (p=0.03), ceftriaxone (p=0.024) and gentamicin (p=0.015) was more frequent in FR strains. Among the 29 (7.5%) ESBL-EC, 27 (93.1%) were FS. In the univariate analysis FR was associated to older age (p=0.048), dementia (p=0.028) and recent FQ use (p=0.036). The frequency of FR remained stable over the study while there was an increase in the proportion of ESBL-EC (chi square for linear trend 17.4; p<0.001) (Fig. 1).

The overall prevalence of FR was comparable with that previously reported in Spain6 and lower when focusing in ESBL-EC strains.6,7 The low frequency of FR in E. coli despite extensive use of fosfomycin has been attributed to a decreased bacterial fitness.8 However, Spanish studies have suggested the existence of a correlation between fosfomycin consumption and FR in E. coli isolates, mainly in ESBL-EC.6,9 Resistance to fosfomycin is generally related to chromosomal mutations in the target or in the transporter genes and less frequently to plasmid modifying enzymes, mainly the fosA3.4 The fosA3 genes, commonly located on a conjugative plasmid that also carries a CTX-M, are widespread in East Asia.4 A high proportion of the analyzed ESBL-EC strains were susceptible to fosfomycin. Interestingly, only 25% of the FR E. coli isolates were ESBL-EC suggesting that the fosA genes are not spread in our environment. However, this could change in case of dissemination of the fosA3 genes, which have already been detected in Europe.10

We found that older age, dementia and FQ consumption were associated to FR. Nursing home residence has been described as a predictor of FR in ESBL-EC.6 Further studies are required to fully evaluate the risk factors of FR in E. coli.

Our study suggests that FR has not increased over time. Most E. coli isolates were FS including ESBL-EC. Risk factors for FR should be considered when prescribing fosfomycin to males with a FUTI.