Despite the huge advance that antiretroviral therapy represents for the prognosis of infection by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), opportunistic infections (OIs) continue to be a cause of morbidity and mortality in HIV-infected patients. OIs often arise because of severe immunosuppression resulting from poor adherence to antiretroviral therapy, failure of antiretroviral therapy, or unawareness of HIV infection by patients whose first clinical manifestation of AIDS is an OI.

The present article updates our previous guidelines on the prevention and treatment of various OIs in HIV-infected patients, namely, infections by parasites, fungi, viruses, mycobacteria, and bacteria, as well as imported infections. The article also addresses immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome.

A pesar del gran avance que ha supuesto el tratamiento antirretroviral (TAR) para el pronóstico de la infección por el VIH, las infecciones oportunistas (IO) continúan siendo causa de morbilidad y mortalidad en estos pacientes. Ello ocurre en muchos casos debido a la inmunodepresión grave, bien ante la falta de adherencia al TAR, el fracaso del mismo o el desconocimiento de la existencia de la infección por el VIH en pacientes que comienzan con una IO.

El presente artículo actualiza las recomendaciones de prevención y tratamiento de diferentes infecciones en pacientes con infección por VIH: parasitarias, fúngicas, víricas, micobacterianas, bacterianas e importadas, además del síndrome de reconstitución inmune.

Opportunistic infections (OIs) have been the main cause of morbidity and mortality in HIV-infected patients since the beginning of the HIV epidemic.1

Efficacious regimens for primary and secondary prophylaxis to prevent OIs were the first major advance in therapy for HIV-infected patients, significantly decreasing mortality, even before the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy (ART).2 ART brought about a notable change in the progression of HIV infection by dramatically reducing mortality and the incidence of OIs.3 However, today, we continue to see cases of OI in various settings: patients who are unaware of their HIV infection and whose first manifestation is an OI; patients who do not receive ART; and failure of ART due to poor adherence or other causes.4 Accordingly, treatment of OIs continues to be a relevant topic in the care of HIV-infected patients.

The present document is an update of our previous recommendations on prevention and treatment of OIs in HIV-infected patients.5,6 The strength of the recommendation and ranking of the tests that support it are based on a modification of the criteria of the Infectious Diseases Society of America.7 According to these criteria, each recommendation should be offered always (A), generally (B), or optionally (C), based on data from 1 or more randomized clinical trials with clinical or laboratory results (I), 1 or more nonrandomized trials or observational cohort data (II), or expert opinion (III).

Owing to space limitations, the reader should consult the tables, which display the various prophylaxis and treatment regimens (both preferred and alternative) and the corresponding doses.

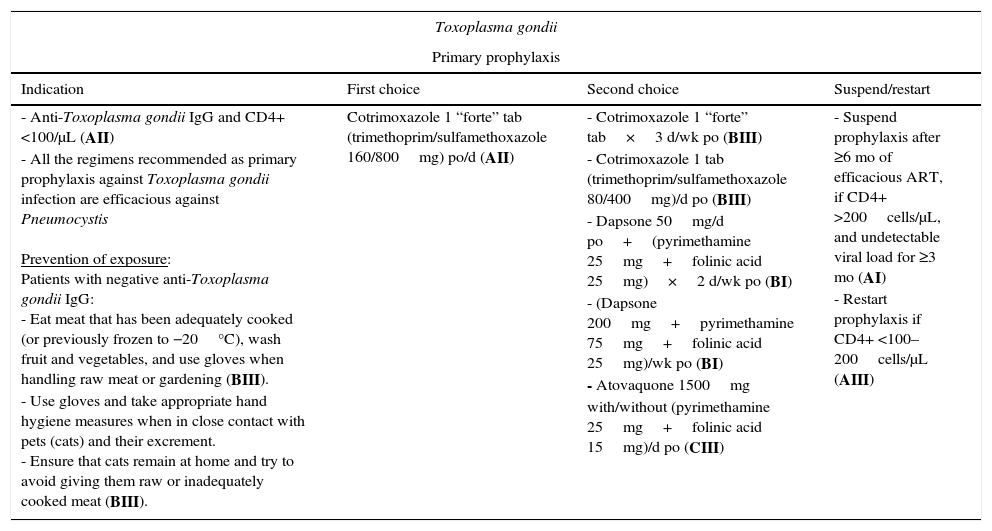

Parasitic infections (Table 1)Toxoplasma gondiiPatients who have not been exposed to Toxoplasma gondii (confirmed by a negative anti-Toxoplasma gondii IgG result) should avoid contact with the parasite. Handwashing is recommended after contact with animals, especially cats, and after handling raw meat. Patients should try to eat meat that has been adequately cooked (or previously frozen to −20°C) and wash fruit and vegetables that are to be eaten raw (BIII).5,8,9

Regimens recommended for prevention and treatment of parasitic infections.

| Toxoplasma gondii | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary prophylaxis | |||

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| - Anti-Toxoplasma gondii IgG and CD4+ <100/μL (AII) - All the regimens recommended as primary prophylaxis against Toxoplasma gondii infection are efficacious against Pneumocystis Prevention of exposure: Patients with negative anti-Toxoplasma gondii IgG: - Eat meat that has been adequately cooked (or previously frozen to −20°C), wash fruit and vegetables, and use gloves when handling raw meat or gardening (BIII). - Use gloves and take appropriate hand hygiene measures when in close contact with pets (cats) and their excrement. - Ensure that cats remain at home and try to avoid giving them raw or inadequately cooked meat (BIII). | Cotrimoxazole 1 “forte” tab (trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 160/800mg) po/d (AII) | - Cotrimoxazole 1 “forte” tab×3 d/wk po (BIII) - Cotrimoxazole 1 tab (trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 80/400mg)/d po (BIII) - Dapsone 50mg/d po+(pyrimethamine 25mg+folinic acid 25mg)×2 d/wk po (BI) - (Dapsone 200mg+pyrimethamine 75mg+folinic acid 25mg)/wk po (BI) - Atovaquone 1500mg with/without (pyrimethamine 25mg+folinic acid 15mg)/d po (CIII) | - Suspend prophylaxis after ≥6 mo of efficacious ART, if CD4+ >200cells/μL, and undetectable viral load for ≥3 mo (AI) - Restart prophylaxis if CD4+ <100–200cells/μL (AIII) |

| Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | First choice | Second choice | Remarks |

| Focal CNS lesions (abscesses), chorioretinitis | Pyrimethamine 200mg po (loading dose), followed by: - Pyrimethamine 50mg/d po+sulfadiazine 1000mg/6h po (if <60kg) or - Pyrimethamine 75mg/d po+sulfadiazine 1500mg/6h po (if ≥60kg) Add folinic acid 15mg/d po in all cases (AI) | - Pyrimethamine 50–75mg/d po+clindamycin 600mg/6h IV or po+folinic acid 15mg/d po (AI) - Cotrimoxazole (trimethoprim 5mg/kg/d+sulfamethoxazole 25mg/kg/d) IV or po in 3–4 doses (BI) - Atovaquone 1500mg/12h po+pyrimethamine 50–75mg/d po (and folinic acid 15mg/d po) or+sulfadiazine 1000–1500mg/6h (BII) - Pyrimethamine 50–75mg/d po+azithromycin 900–1200mg/d po+folinic acid 15mg/d po (CII) | - Minimum duration: 6wk (prolong in extensive disease and/or slow/incomplete response) (BII) - Regimen based on clindamycin (as opposed to sulfadiazine) does not protect against pneumocystosis (add specific prophylaxis) (AII) - In cases of intracranial hypertension, add dexamethasone (BIII) - In cases of epilepsy, add anticonvulsant treatment (not as prophylaxis) (AIII) |

| Secondary prophylaxis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| All patients who have completed treatment of acute infection | - Pyrimethamine 25–50mg/d po+sulfadiazine 1000mg/6–12h po+folinic acid 15mg/d po (AI) | - Pyrimethamine 25–50mg/d po+clindamycin 600mg/8h po+folinic acid 15mg/d po (BI) - Cotrimoxazole 1 “forte” tab/12h po (BII) - Atovaquone 750–1500mg/12h po+pyrimethamine 25mg/d po (and folinic acid 15mg/d po) or sulfadiazine 1000mg/6–12h (BII) - Pyrimethamine 25–50mg/d po+azithromycin 500–1000mg/d po+folinic acid 15mg/d po | - Suspend prophylaxis if CD4+ >200cells/μL and ART >6 mo, with undetectable viral load (BI) - Restart prophylaxis if CD4+ <200cells/μL (AIII) |

| Leishmania spp. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary prophylaxis | |||

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| Prevention of exposure: Canine health surveillance (in endemic areas), use of insecticide and prevention of sandfly bites | No indication | Not applicable | |

| Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | First choice | Second choice | Remarks |

| Visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar): systemic disease, possible atypical local involvement | Liposomal amphotericin B 2–4mg/kg/d IV (AII) or 4mg/kg on days 1–5, 10, 17, 24, 31, and 38 (AII) in both cases until a total dose of 20–60mg/kg has been reached (AII) | - Amphotericin B lipid complex 3mg/kg/d IV (10 d) - Amphotericin B 0.5–1mg/kg/d IV (total dose, 1.5–2g) (BII) - Pentavalent antimony 20mg/kg/d IV or IM ×4wk (BII) - Miltefosine 100mg/d po ×4 wk (CIII) | - Initiation (or optimization) of ART is essential - Some in vitro results (increased replication of HIV) cast doubt on the indication of pentavalent antimonials |

| Secondary prophylaxis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| As continuation of treatment of the acute infection, especially in patients with CD4+ <200cells/μL | - Liposomal amphotericin B 4mg/kg/2–4wk (AII) - Amphotericin B lipid complex 3mg/kg/3wk (BI) | - Pentavalent antimony 20mg/kg IV or IM every 4wk (BII) - Miltefosine 100mg/d po (CIII) - Pentamidine 300mg/3–4wk IV (CIII) | - Suspend prophylaxis if CD4+ >200–350cells/μL, for >3 mo, with ART and undetectable viral load and no relapse of leishmaniasis during the previous 6 months (no consensus: some experts recommend indefinite secondary prophylaxis) - Restart prophylaxis if CD4+ <200cells/μL |

| Cryptosporidium spp. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary prophylaxis | |||

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| Prevention of exposure: - Avoid consumption of contaminated water or raw foods (e.g., oysters, fruit, and vegetables). Ensure strict hygiene measures in cases of contact with infected persons or animals (BIII) | - There are no efficacious specific measures - Early ART prevents profound immunodepression and infection by Cryptosporidium | Not applicable | |

| Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | First choice | Second choice | Remarks |

| Mainly affects patients with CD4+ <100cells/μL - Enteritis with acute/chronic watery diarrhea - Possible sclerosing cholangitis or pancreatitis | Start ART to achieve immune recovery (CD4+ >100cells/μL) (AII) | Can be administered as a complement to ART (CIII): - Nitazoxanide 500–1000mg/12h po (14 d) o - Paromomycin 500mg/6h po (14–21 d) | - Take strong measures to replace electrolytes (orally and IV) (AIII) - Symptomatic treatment of diarrhea with intestinal motility inhibitors (AIII) |

| Secondary prophylaxis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| After acute infection | Maintain ART to ensure sustained immune recovery | Not applicable | |

| Microsporidia | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary prophylaxis | |||

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| Prevention of exposure: - Hand hygiene and avoid contact with/exposure to contaminated water | - No specific efficacious measures | Not applicable | |

| Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | First choice | Second choice | Remarks |

| More frequent involvement if CD4+ <100cells/μL - Enteritis with watery diarrhea - Disseminated infection, e.g., keratoconjunctivitis, hepatitis, encephalitis | Start ART to achieve immune recovery (AII)+specific therapy: Gastrointestinal involvement - Enterocytozoon bieneusi: Fumagillin 20mg/8h po (BIII) - Other species: Albendazole 400mg/12h po (AII) Ocular involvement - Topical fumagillin (BII)+albendazole 400mg/12h po (BIII) | Gastrointestinal involvement Nitazoxanide 1000mg/12h po (CIII) Disseminated disease caused byTrachipleistophora species or Anncaliia species: Itraconazole 400mg/d po+albendazole 400mg/12h po (CIII) | If diarrhea is intense, intestinal motility drugs could prove useful (BIII) |

| Secondary prophylaxis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| After acute infection | Prolong treatment until clinical cure and immune recovery | - Suspend if clinical cure, with CD4+ >200cells/μL and ART >6 mo, with undetectable viral load (CIII) - No recommendations on restarting prophylaxis | |

| Isospora belli | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary prophylaxis | |||

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| Prevention of exposure: - Avoid contact with contaminated food and water, especially in tropical and subtropical areas | Oral cotrimoxazole (trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole) could reduce the incidence of isosporiasis, although evidence is insufficient | Not applicable | |

| Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | First choice | Second choice | Remarks |

| Enteritis and, exceptionally, extraintestinal involvement | - Cotrimoxazole po or IV (trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole) 160/800mg/6h ×10 d (AII) or 160/800mg/12h ×7–10 d (BI) | - Pyrimethamine 50–75mg/d po+folinic acid 15mg/d po (BIII) - Ciprofloxacin 500mg/12h po ×7 d (CI) | Adjust cotrimoxazole according to severity and patient's response (BIII) If necessary, administer nutritional and electrolyte supplements (AIII) |

| Secondary prophylaxis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| After acute infection, if CD4+ <200cells/μL | Cotrimoxazole (trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole) 160/800mg ×3 d/wk po (AI) or 160/800mg/d po or 320/1600mg ×3 d/wk po (BIII) | - Pyrimethamine 25mg/d po+folinic acid 15mg/d po (BIII) - Ciprofloxacin 500mg ×3 d/wk po (CI) | - Suspend if no symptoms, CD4+ >200cells/μL, and ART >6 mo, with undetectable viral load (BIII) - No recommendations on restarting prophylaxis |

Primary prophylaxis should be with cotrimoxazole in patients with anti-Toxoplasma gondii IgG and a CD4+ T-lymphocyte count <100cells/μL (AII); alternatives include pyrimethamine combined with dapsone or atovaquone.5,8,9 These regimens also protect against Pneumocystis jiroveci infection. Inhaled pentamidine does not protect against Toxoplasma gondii infection.

When cerebral toxoplasmosis is suspected, treatment should be started with sulfadiazine combined with pyrimethamine (and folinic acid to reduce blood toxicity) (AI) and maintained for at least 6 weeks (BII).6,8,9 A brain biopsy should be performed if no response is observed at 7–14 days. If the diagnosis is confirmed, switching treatment to clindamycin+pyrimethamine (with folinic acid) should be considered (AI).6,8,9 If therapy cannot be administered through a nasogastric tube, intravenous cotrimoxazole can be used (BI).10 Dexamethasone should be used in cases of intracranial hypertension (BIII). Treatment with anticonvulsants—preferably levetiracetam—should be added in patients who experience convulsions (AIII).6,8,9

Once treatment is complete, secondary prophylaxis can be started (same regimen, reduced dose) (AI).5,8,9

Prophylaxis can be discontinued after 6 months on ART, providing the patient has maintained an undetectable viral load and a CD4+ T-lymphocyte count >200cells/μL for ≥3 months (primary) or ≥6 months (secondary) (AI),11 probably owing to recovery of the anti-Toxoplasma gondii cellular response (CD4+ T lymphocytes).12 Prophylaxis should be restarted if the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count returns to <100–200cells/μL (AIII).5,8,9

Leishmania speciesPrevention of exposure to parasites of Leishmania species should be based on canine health surveillance in regions where the disease is prevalent (Mediterranean basin, where L. infantum is predominant) and avoiding exposure to dogs (especially in the case of immunodepressed patients) (CIII), sandfly bites, and needle sharing. There are no primary prophylaxis measures.5,8,9

The treatment of choice for visceral leishmaniasis is liposomal amphotericin B (AII) or amphotericin B lipid complex,6,8,9 in various regimens. Alternatives include amphotericin B deoxycholate (renal toxicity) or pentavalent antimonials (pancreatic and cardiac toxicity) (BII). The efficacy of miltefosine and paromomycin has not been demonstrated in HIV-infected patients (CIII).13

Secondary prophylaxis should be administered once the acute infection has been treated (BII). Lipid formulations of amphotericin B (liposomal [AII] or lipid complex [BI]) are also drugs of choice.5,8,9 In cases of relapse (common in very immunodepressed patients), it is necessary to repeat the initial treatment, use another regimen,6,8,9 or administer a combination of the drugs mentioned above.

No safe recommendation can be made about withdrawal of secondary prophylaxis against Leishmania.5,8,9 Although some experts recommend maintaining prophylaxis indefinitely, suspension should be considered in patients who remain relapse-free for 6 months, maintain a CD4+ T-lymphocyte count >200–350cells/μL and an undetectable viral load for >3 months, and, if possible, test negative in PCR for the Leishmania antigen in blood or urine14 (CIII). Prophylaxis should be restarted if the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count falls to <200cells/μL.5,8,9

Cryptosporidium species, microsporidia, and Isospora belliThese ubiquitous parasites (Isospora belli predominates in tropical areas) cause mainly intestinal infection. As they are transmitted through contaminated food and water, contact should be avoided and appropriate hand hygiene measures should be taken to prevent exposure.5,8,9 There are no efficacious primary prophylaxis regimens.

There is no specific treatment for cryptosporidiosis (CIII), and cure is based on ART-associated immune recovery (AII).6,8,9 Treatment of microsporidiosis also depends on ART (AII), although efficacious complementary drugs are available. In intestinal infections and infections caused by Enterocytozoon bieneusi, the treatment of choice is oral fumagillin (BIII). Albendazole is recommended if other species are involved (AII). In patients with ocular involvement, albendazole can be combined with topical fumagillin (BIII).6,8,9 The treatment of choice for isosporiasis is cotrimoxazole (BI).6,8,9

Secondary prophylaxis for microsporidiosis and isosporiasis involves maintaining the same regimen as for treatment. This can be suspended when a CD4+ T-lymphocyte count >200cells/μL is reached after 6 months of efficacious ART (CIII and BIII, respectively). Suspension would be questionable in ocular microsporidiosis.5,8,9 In a recent report, isosporiasis persisted despite appropriate prophylaxis and treatment and optimal immune recovery.15

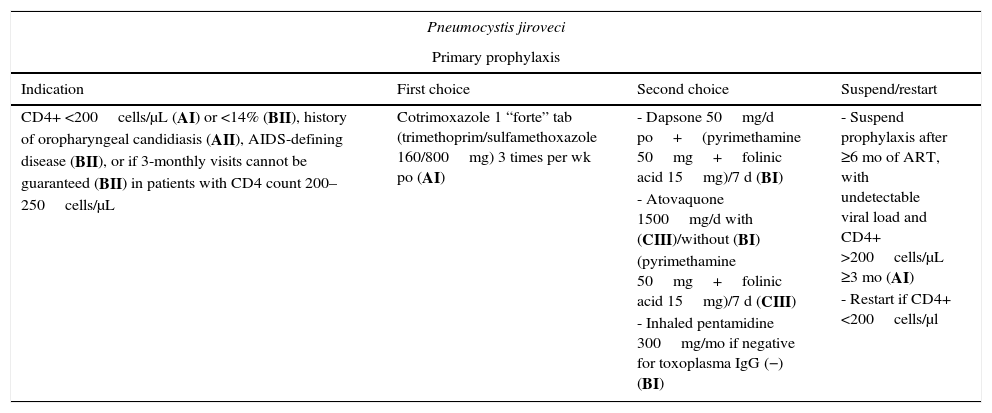

Fungal infections (Table 2)Pneumocystis jiroveciPrevention of exposure. Although available epidemiologic data indicate that respiratory isolation should be considered in patients with Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, there is insufficient evidence to support this recommendation (CIII).16

Recommended regimens for the prevention and treatment of fungal infections.

| Pneumocystis jiroveci | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary prophylaxis | |||

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| CD4+ <200cells/μL (AI) or <14% (BII), history of oropharyngeal candidiasis (AII), AIDS-defining disease (BII), or if 3-monthly visits cannot be guaranteed (BII) in patients with CD4 count 200–250cells/μL | Cotrimoxazole 1 “forte” tab (trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 160/800mg) 3 times per wk po (AI) | - Dapsone 50mg/d po+(pyrimethamine 50mg+folinic acid 15mg)/7 d (BI) - Atovaquone 1500mg/d with (CIII)/without (BI) (pyrimethamine 50mg+folinic acid 15mg)/7 d (CIII) - Inhaled pentamidine 300mg/mo if negative for toxoplasma IgG (−) (BI) | - Suspend prophylaxis after ≥6 mo of ART, with undetectable viral load and CD4+ >200cells/μL ≥3 mo (AI) - Restart if CD4+ <200cells/μl |

| Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | First choice | Second choice | Remarks |

| P jiroveci pneumonia | Severe forms: - Cotrimoxazole 15–20/75–100mg/kg/d in 3–4 doses IV+oral prednisone (days 1–5: 40mg bid; days 6–10: 40mg qd; days 11–21: 20mg qd (AI) Mild forms: Cotrimoxazole at same doses po (AI) | - Clindamycin 600mg IV/po 6–8h+primaquine 30mg/d po (BI). Rule out G6PDH deficiency before administering primaquine - Pentamidine 4mg/kg/d IV×21 d (BI) - Atovaquone 750mg/12h po in mild forms (BI) | Severe forms: pO2 <70mmHg or alveolar-capillary gradient >35mmHg. When the patient's condition improves, treatment can be switched to oral cotrimoxazole |

| Secondary prophylaxis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| All patients who have completed treatment of acute infection (AI) | Cotrimoxazole 1 “forte” tab (trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 160/800mg) po/d (AI) | - Dapsone 50mg/d po+(pyrimethamine 50mg+folinic acid 15mg)/7 d (BI) - Atovaquone 1500mg/d with(out) (pyrimethamine 50mg+folinic acid 15mg)/7 d (BI) | - Suspend prophylaxis after ≥6 mo of ART, undetectable viral load and if CD4+ >200cells/μL ≥3 mo (AI) - Restart if CD4+ <200cells/μl or relapse |

| Cryptococcus species | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary prophylaxis | |||

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| No indication | |||

| Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | First choice | Second choice | Remarks |

| Infection by Cryptococcus species | Induction (2 wk): - Lipid amphotericin* IV+flucytosine 25mg/kg/6h po (AI) Maintenance: - Fluconazole 400mg/d po×10 wk (AI) | Induction: - Lipid amphotericin* IV+fluconazole 800mg/d IV/po (BII) - Fluconazole 800–1200mg/d IV/po±flucytosine (BII) Maintenance: - Itraconazole 200mg/d po (BII) | - Defer initiation of ART 5wk (AI) - In patients with meningitis and intracranial hypertension, repeated lumbar puncture or CSF shunt (BIII) |

| Secondary prophylaxis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| As continuation of treatment of acute infection | - Fluconazole 200mg/d po (AI) | - Lipid amphotericin* every 7 d (BIII) - Itraconazole 200mg/d po (BIII) | - Suppress prophylaxis if CD4+ >100cells/μL and undetectable viral load for 3 mo (BII) |

| Candida species | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary prophylaxis | |||

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/Restart |

| No indication | |||

| Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | First choice | Second choice | Remarks |

| Signs and/or symptoms of oral, esophageal, or vulvovaginal disease | Oral: - Fluconazole 100mg/d×7–14 d (AI) Esophageal: Fluconazole 100–200mg/d po×7–14 d (AI) In cases of oral intolerance, fluconazole IV (up to 400mg/d) (AI) Vulvovaginitis: - Fluconazole 150mg/d in a single dose (AII) | Oral (for 7–14 d): - Itraconazole 200mg/d (BI) - Posaconazole 400mg/d (BI) - Clotrimazole 10mg 4–5 times per day (BI) - Nystatin suspension 5ml/6h (BI) - Miconazole oral gel 125mg/6h (BI) Esophageal (×7–14 d): - Caspofungin 70mg first day followed by 50mg/d IV (AI) - Voriconazole 200mg/d (BI) - Itraconazole 200mg/d (BI) - Posaconazole 400mg/d (BI) - Micafungin 150mg/d IV (BI) Vulvovaginitis (×3–7 d): - Topical clotrimazole (AII) - Topical miconazole (AII) | |

| Secondary prophylaxis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| No indication | |||

| Aspergillus species | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary prophylaxis | |||

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| No indication | |||

| Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | First choice | Second choice | Remarks |

| Focal or disseminated disease | Induction: - Voriconazole 6mg/kg/12h IV on day 1 followed by 4mg/kg/12h IV on subsequent days (AI) Maintenance: - Voriconazole 200mg/12h po (AI) | - Lipid amphotericin* (AII) - Caspofungin 70mg on day 1 followed by 50mg/d IV (BIII) - Micafungin 100–150mg/d IV (BIII) - Anidulafungin 200mg el on day 1 followed by 100mg IV/d (BIII) - Posaconazole 400mg/12 po (BIII) | Duration not established, but should be maintained until immune recovery (CD4+ >200cells/μL) |

| Secondary prophylaxis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| No indication | |||

| Histoplasma capsulatum | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary prophylaxis | |||

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/Restart |

| No indication | |||

| Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | First choice | Second choice | Remarks |

| Focal or disseminated disease | Severe disease: - Lipid amphotericin*×2 wk (AI) followed by itraconazole 200mg/8h po×3 d subsequently 200mg/12h >12 mo (AII) Meningitis: - Lipid amphotericin*×4–6wk followed by itraconazole 200mg/8–12h po >12 mo (AIII) Mild disease: - Itraconazole 200mg/12h po (AII) | Mild disease: - Posaconazole 400mg/12h po (BIII) Voriconazole 400mg/12h po×1 d followed by 200mg/12h po (BIII) - Fluconazole 800mg/d po (CII) | - H capsulatum is resistant to echinocandins |

| Secondary prophylaxis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| After treatment of acute infection for 12 mo | - Itraconazole 200mg/d (AIII) | - Fluconazole 400mg/d po (BIII) | - Suppress prophylaxis if CD4+ >150cells/μL×6 mo and serum antigen <2ng/mL (AI). |

| Coccidioides immitis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary prophylaxis | |||

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/Restart |

| No indication | |||

| Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | First choice | Second choice | Remarks |

| Focal or disseminated disease | Disseminated disease: - Lipid amphotericin* until improvement followed by fluconazole 400–800mg/d po or itraconazole 200mg/12h po (AII) Meningitis: - Fluconazole 400–800mg/d IV/po (AII) Pneumonia: - Fluconazole 400mg/d (BII) - Itraconazole 200mg/12h po (BII) | Disseminated disease: - Combine lipid amphotericin* with fluconazole 400mg/d or itraconazole 400mg/d (BIII) Meningitis: - Itraconazole 200mg/8h po×3 d followed by 200mg/12h (BIII) - Posaconazole 200mg/12h po (BIII) - Voriconazole 200–400mg/12h po (BIII) - Administer intrathecal amphotericin if triazoles fail (AIII) Pneumonia: - Posaconazole 200mg/12h po (BII) - Voriconazole 200mg/12h po (BIII) | - Use in meningitis. Use intrathecal amphotericin B if triazoles fail. |

| Secondary prophylaxis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| After acute infection indefinitely | - Fluconazole 400mg/d po (AII) - Itraconazole 200mg/12h po (AII) | - Posaconazole 200mg/12h po (BII) - Voriconazole 200mg/12h po (BIII) | In patients with pneumonia, suspend prophylaxis if CD4+ >250cells/μL for >12 mo (AII) |

| Penicillium marneffei | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary prophylaxis | |||

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| No indication | |||

| Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | First choice | Second choice | Remarks |

| Severe disease: - Lipid amphotericin*×2wk followed by itraconazole 200g/12h po×10wk (AII) Mild disease: - Itraconazole 200mg/12h po×8–12wk (BII) | Severe disease: - Voriconazole 6mg/kg/12h IV×1 d, 4mg/kg/12h IV×3 d, 200mg/12h po×8–12wk (BII) Mild disease: - Voriconazole 400mg/12h po 1 d followed by 200mg/12h po (BII) | - P. marneffei is resistant to fluconazole | |

| Secondary prophylaxis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/Restart |

| After acute infection | - Itraconazole 200mg/d po (AI) | Suppress prophylaxis if CD4+ >100cells/μL for ≥6 mo (BII) | |

Primary prophylaxis is indicated in patients with a CD4+ T-lymphocyte count <200cells/μL (AI), previous oropharyngeal candidiasis (AII), CD4+ <14% (BII), or a previous AIDS-defining disease (BII). It should be considered in patients with 200–250 CD4+ cells/μL if 3-monthly visits cannot be guaranteed (BII). Secondary prophylaxis is always indicated in patients with a history of pneumonia (AI).

Cotrimoxazole is the drug of choice both for primary and for secondary prophylaxis (AI). Patients with hypersensitivity can undergo desensitization or receive alternatives such as dapsone/pyrimethamine (BI) or atovaquone with(out) pyrimethamine (BI). Inhaled pentamidine does not prevent extrapulmonary involvement; if this drug is used, it should be restricted to patients with negative toxoplasma serology results (BI). Prophylaxis can be suspended if the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count exceeds 200cells/μL for at least 3 months after starting ART (A1).17 Some data suggest that primary prophylaxis could be suspended even with 100–200cells/μL and an undetectable viral load (CIII).18 A recent study in children and adolescents in Africa showed that maintenance of prophylaxis with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in patients with >200 CD4+ cells/μL reduced the risk of admission for bacterial infections and malaria (CI).19

Intravenous cotrimoxazole (21 days) is the treatment of choice for P. jiroveci pneumonia (AI). Treatment can be administered orally when the patient's condition improves or when the disease is mild/moderate (AI). Folinic acid is not recommended because it can increase the risk of therapeutic failure. Patients with moderate/severe disease (pO2 <70mmHg or alveolar-capillary gradient >35mmHg) should start therapy with corticosteroids combined with cotrimoxazole (AI). Alternative treatments include clindamycin+primaquine or intravenous pentamidine or atovaquone (BI), although atovaquone should only be administered in mild cases.

Cryptococcus neoformansPrimary prophylaxis for infection by Cryptococcus neoformans is not indicated in Spain owing to the low incidence of the disease.

Induction treatment of meningitis should be with liposomal amphotericin+flucytosine for at least 2 weeks (AI). Alternatives include liposomal amphotericin+fluconazole or fluconazole with(out) flucytosine (BII). After 2 weeks of treatment, the regimen can be switched to fluconazole for at least 10 weeks, providing that the patient's condition has improved and the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) culture is negative (AI). Initiation of ART should be deferred by 5 weeks owing to the risk of greater mortality associated with early initiation20 (AI). Cryptococcal meningitis is often associated with increased intracranial pressure, which is treated using repeated lumbar puncture or even placement of a CSF shunt (BIII). In extrameningeal forms, the treatment of choice is fluconazole (400mg/d) or liposomal amphotericin if the patient's condition is severe (AIII).

Secondary prophylaxis is always indicated once at least 10 weeks of treatment has been completed. The drug of choice is fluconazole (AI). Alternatives include itraconazole or weekly liposomal amphotericin (BIII). Secondary prophylaxis can be suspended when the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count exceeds 100cells/μL with an undetectable viral load for at least 3 months (BII).21

Candida albicansPrimary prophylaxis of infections by Candida species is not indicated owing to the scarce morbidity and mortality associated with this disease and the risk of resistance.

Fluconazole is the treatment of choice for oral and esophageal candidiasis (AI). Alternatives include itraconazole and posaconazole (BI). In cases of exclusively oropharyngeal involvement, treatment is with topical clotrimazole or miconazole. Alternatives include nystatin suspension (BI). In the case of esophagitis, and depending on the severity of the condition, it may be necessary to use intravenous fluconazole (AI), with voriconazole or echinocandins as alternatives (in patients with resistance or toxicity) (BI).22 If no improvement is observed after 7 days of treatment, other microorganisms should be ruled out using endoscopy in the case of esophagitis and/or ruling out resistance to azoles.

Vulvovaginitis caused by Candida species can be treated with oral fluconazole (AII) or topical clotrimazole or miconazole (AII).

Secondary prophylaxis is not recommended. Fluconazole (3 times weekly) can be used in the case of very frequent relapses (CIII). However, in these cases, recurrence at any site should be considered indicative of azole resistance.6

Aspergillus fumigatusPrimary prophylaxis is not recommended.

The treatment of invasive aspergillosis depends on the severity of symptoms.22 Voriconazole is generally considered the drug of choice (AI). Alternatives include liposomal amphotericin (AII), caspofungin, and posaconazole (BIII). ART should be started as soon as possible, and potential drug interactions should be evaluated. The optimal duration remains unknown, although treatment should be maintained at least until the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count is >200cells/μL.

The lack of data prevents us from making recommendations on secondary prophylaxis.

Histoplasma capsulatumPrimary prophylaxis is not recommended in Spain.

Treatment of severe infections is with liposomal amphotericin (AI) for 2 weeks,23 followed by itraconazole for 12 months (AII) (monitor levels after 2 weeks to ensure >1μg/mL). In patients with meningitis, administer liposomal amphotericin for 4–6 weeks (AIII) followed by itraconazole for at least 12 months (AIII). In mild forms, the drug of choice is itraconazole (AII). Alternatives include posaconazole and voriconazole (BIII) or fluconazole (CII). Histoplasma capsulatum is resistant to echinocandins.

Secondary prophylaxis is always indicated after 12 months of treatment and is with itraconazole (AIII) or fluconazole (less efficacious) (BIII). It can be suspended when the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count is >150cells/μL for at least 6 months with undetectable HIV viral load and serum antigen <2ng/mL (AI). Secondary prophylaxis should be restarted if the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count falls below 150cells/μL (BIII).24

Coccidioides immitisPrimary prophylaxis is not indicated in Spain.6

Pneumonia should be treated with fluconazole or itraconazole (BII). Alternatives include posaconazole (BII) and voriconazole (BIII). Disseminated disease is treated with liposomal amphotericin until the patient's clinical condition improves (AII) and then with fluconazole or itraconazole. Some experts recommend combining liposomal amphotericin with a triazole (BIII). Meningitis is treated with fluconazole (AII) or with itraconazole, posaconazole, or voriconazole (BIII). Intrathecal amphotericin B should be used if treatment with triazoles is inefficacious (AIII). If possible, the response should be monitored using serum antibody titers.

Secondary prophylaxis is always indicated with fluconazole or itraconazole (AII). In the absence of a response, posaconazole (BII) or voriconazole (BIII) can be administered. Given the high risk of relapse, indefinite prophylaxis is recommended in meningitis (AII) and in disseminated disease (BIII). Secondary prophylaxis can be suspended after >12 months in patients with a CD4+ T-lymphocyte count >250cells/μL (AII).

Blastomyces dermatitidisProphylaxis and treatment are similar to those of histoplasmosis.

Penicillium marneffeiPrimary prophylaxis is not recommended in Spain.

Treatment of the severe form is with liposomal amphotericin for 2 weeks followed by itraconazole for a further 10 weeks (AII). Voriconazole can be used as an alternative during the first 12 weeks (BII). Mild disease is treated with itraconazole (BII) or voriconazole (BII) for 8–12 weeks. P. marneffei is resistant to fluconazole.

Secondary prophylaxis, which is always indicated, is with itraconazole (AI).25 It can be suspended when the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count exceeds 100cells/μL for at least 6 months and HIV viral load remains suppressed (BII). It should be restarted if the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count falls again (AIII) or the patient experiences a recurrence with >100cells/μL (CIII).

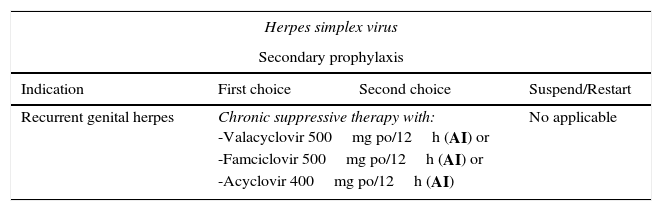

Viral infectionsHerpes simplex virusThe most common clinical forms of herpes simplex virus (HSV) are genital herpes, which is generally caused by HSV-2, and orolabial herpes, which is usually caused by HSV-1. Recurrences are more common in genital herpes. Treatment is more efficacious if started early, during the prodromal phase, or on the day immediately following the appearance of lesions.

Antiviral therapy with nucleoside analogs is efficacious, safe, and well-tolerated. In genital herpes, it can reduce the risk of transmission of HIV-1.

Treatment of herpesvirus encephalitis is similar in HIV-infected patients and immunocompetent patients. It should be started empirically as soon as the diagnosis is suspected.

Herpetic proctitis and esophagitis respond to systemic acyclovir. Treatment is usually started intravenously and continued orally.

The possibility of resistance to antiviral drugs must be taken into consideration when lesions do not improve after 7–10 days of correctly administered treatment. Resistance should be confirmed using a sensitivity study.

Primary prophylaxis is not recommended. No vaccines are available. Secondary prophylaxis should be considered in the case of severe recurrence or to reduce the number of recurrences.26

Varicella zoster virusThe incidence of infections by varicella zoster virus (VVZ) is much greater in HIV-infected patients than in the general population. VVZ infection can appear regardless of the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count. VVZ infection in adults with no known causes of immunosuppression requires HIV infection to be ruled out. The presentation and clinical course of VVZ infection can be modified in patients with advanced immunosuppression. Retinal necrosis is one of the best-characterized clinical syndromes in patients with VVZ infection.

Treatment of localized herpes zoster infection is aimed at preventing dissemination of infection (especially in immunodepressed patients and patients aged >50 years), reducing the duration of symptoms, and reducing the risk of postherpetic neuralgia. Corticosteroids are not recommended.

Initiation of acyclovir IV is recommended in patients with varicella, disseminated herpes zoster infection, or visceral involvement (see Table 3 for levels of evidence).27 Acute retinal necrosis usually responds to treatment with high-dose intravenous acyclovir, which can be continued with oral valacyclovir (BIII). Intravitreal treatment can also be considered in some cases (BII).28

Recommended regimens for prevention and treatment of viral infections.

| Herpes simplex virus | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary prophylaxis | |||

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/Restart |

| Recurrent genital herpes | Chronic suppressive therapy with: -Valacyclovir 500mg po/12h (AI) or -Famciclovir 500mg po/12h (AI) or -Acyclovir 400mg po/12h (AI) | No applicable | |

| Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | First choice | Second choice | Remarks |

| Orolabial or nonsevere genital herpes Orolabial or severe genital herpes Herpes encephalitis | -Valacyclovir 1g po/12h, or -Famciclovir 500mg po/12h, or -Acyclovir 400mg po/8h, Orolabial (AIII) 5–10 d, genital (AI) 5–14 d -Initial treatment with acyclovir 5mg/kg/8h IV until lesions begin to regress and continue with one of the oral regimens mentioned above until the lesions have resolved (AIII) -Acyclovir 10mg/kg/8h IV for 14–21 d (AIII) | - Herpes refractory or resistant to acyclovir, -Foscarnet 40mg/kg IV/8h or 60mg/kg IV/12h (AI), or -Cidofovir 5mg/kg/wk IV or topical treatment with cidofovir, trifluridine, or imiquimod (compounded formulations) (CIII) | |

| Varicella zoster virus | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary prophylaxis | |||

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/Restart |

| Postexposure prophylaxis Close contact with a person with active varicella or herpes zoster and susceptible to VVZ (no history of vaccination or seronegativity) | Specific immunoglobulin, as soon as possible, within 10 days of exposure (AIII) | - Acyclovir 800mg po 5 times/d or - Valacyclovir 1g/8h po, 5–7 d (BIII) as long as it is started within the 7–10 days following exposure | Not applicable |

| Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | First choice | Second choice | Remarks |

| Uncomplicated varicella Severe forms of varicella Localized herpes zoster Disseminated herpes zoster or herpes zoster with visceral involvement Acute retinal necrosis Rapidly progressive outer retinal necrosis Refractory herpes zoster/acyclovir-resistant VVZ | Duration: 5–7 d -Valacyclovir 1g po/8h (AII), or -Famciclovir 500mg po/8h (AII) -Acyclovir IV 10–15mg/kg/8h for 7–10 d (AIII) (if no visceral involvement, treatment can be completed with oral valacyclovir, famciclovir, or acyclovir) (BIII) Duration: 7–10 d -Valacyclovir 1g po/8h (AII), -Famciclovir 500mg po/8h (AII) Treatment with corticosteroids is not recommended. -Acyclovir 10–15mg/kg/8h IV until clear improvement in skin and/or visceral lesions (AII); oral regimens can then be started for up to 10–14 d (BIII) Acyclovir IV 10–15mg/kg/8h×10–14 d followed by valacyclovir 1g po/8h for 6wk (AIII) ±1 or 2 doses of intravitreal ganciclovir during the first week (BII) (Ganciclovir 5mg/kg±foscarnet 90mg/kg) IV every 12h+(ganciclovir 2mg/0.05mL±foscarnet 1.2mg/0.05mL) administered by intravitreal injection twice weekly (AIII) • Start or optimize ART (AIII) Foscarnet 40mg/kg IV/8h or foscarnet 60mg/kg IV/12h (AII) | - Acyclovir 800mg po, 5 times daily (BII) Acyclovir 800mg po, 5 times daily (BII). Cidofovir 5mg/kg IV weekly for the first 2 weeks, and fortnightly thereafter | |

| Cytomegalovirus | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary prophylaxis | |||

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/Restart |

| The best form of prevention is to maintain CD4+ >100cells/μL with antiretroviral treatment | Not applicable | ||

| Secondary prophylaxis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/Restart |

| Retinitis Other sites | Valganciclovir 900mg/d po (AI) If the patient has received an intraocular implant, this should be replaced every 6–8 mo until the immune system has recovered (BI) There is no evidence that maintenance treatment should be administered. Induction treatment could be extended for a few weeks in cases of slow recovery | Ganciclovir 5mg/kg IV 5–7 d/wk (AI), or Ganciclovir 10mg/kg IV 3 d/wk (BI), or Foscarnet 90–120mg/kg IV 5–7 d/wk (BI), or -Cidofovir 5mg/kg IV every 2 wk with saline solution and probenecid (BI) | Suspend if CD4+ >100cells/μL for at least 3–6 mo |

| Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | First choice | Second choice | Remarks |

Retinitis with risk of blindness Peripheral retinitis Esophagitis or colitis Pneumonitis Neurologic disease Uveitis in a patient with immune reconstitution syndrome | Intravitreal injection of ganciclovir 2mg or foscarnet 2.4mg×1–4 doses over 7–10 d (AIII)+valganciclovir 900mg po/12h for 14–21 d (AI), or a second-choice drug Valganciclovir 900mg po/12h durante 14–21 d (AI) Ganciclovir 5mg/kg/12h IV, which can be switched to oral valganciclovir 900mg/12h as soon as the patient is able to tolerate oral therapy (BI) for 3–4wk or until resolution of symptoms Ganciclovir IV 5mg/kg/12h (CIII) or Foscarnet 60mg/kg/8h IV, or 90mg/kg/12h IV (CIII) for 3–4wk or until symptoms have resolved Ganciclovir IV combined with foscarnet until symptoms have improved (CIII) Periocular corticosteroids or a short cycle of systemic corticosteroids (BIII) | Ganciclovir 5mg/kg/12h IV for 14–21 d (AI) or Foscarnet 60mg/kg/8h IV or 90mg/kg/12h IV for 14–21 d (AI), or Cidofovir 5mg/kg/wk IV for 2wk (BI) Ganciclovir 5mg/kg/12h IV for 14–21 d (AI) or Foscarnet 60mg/kg/8h IV or 90mg/kg/12h IV for 14–21 d (AI), or Cidofovir 5mg/kg/wk IV for 2wk (BI) Foscarnet 60mg/kg/8h, or foscarnet 90mg/kg/12h IV (BI) or Valganciclovir 900mg/12h po in moderate disease and providing the patient can tolerate oral therapy (BII) Ganciclovir+foscarnet (CIII) | Intravitreal injection aims to reach suitable intraocular concentrations quickly |

| Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary prophylaxis | |||

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/Restart |

| The best form of prevention is to maintain CD4+ >100cells/μL with antiretroviral treatment | Not applicable | ||

| Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | First choice | Second choice | Remarks |

| Initiate ART (AII) or optimize ART (AIII) with potent regimens that have good CNS penetration. | Corticosteroids can be used in IRIS occurring with PML (BIII) | ||

| Influenza virus | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary prophylaxis | |||

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/Restart |

| HIV-infected patients should receive the seasonal inactivated influenza vaccine yearly (AI) | Not applicable | ||

Resistance of VVZ to nucleoside analogs is exceptional, although it can emerge and responds to foscarnet.

CytomegalovirusCytomegalovirus (CMV) disease is mainly due to reactivation in severely immunosuppressed patients (CD4+ <50cells/μL). The most common clinical manifestations are retinitis, colitis, esophagitis, pneumonitis, polyradiculoneuritis, and encephalitis. Regular funduscopy is recommended for severely immunodepressed patients, and patients should be advised to see their doctor immediately if they experience visual disturbances. Retinitis is the most common condition. Cases involving an imminent risk of blindness (lesions near the optic nerve or macula) must be treated quickly to preserve vision. Treatment of visceral CMV infection should be on an individual basis depending on the location and severity of the process (Table 3). The treatment of choice is usually oral valganciclovir because of its efficacy, safety, and ease of administration (AI).29 The best results in CMV retinitis with a high risk of loss of vision were obtained with an intraocular ganciclovir implant (BI),30 which is not currently marketed. In these cases, treatment should be started with valganciclovir (AI). A 2-mg dose of intravitreal ganciclovir should also be administered and repeated at 48h (AIII) (Table 3). CMV encephalitis should be treated with ganciclovir+foscarnet (CIII).

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathyART is the only approach to prevent progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) and improve the T lymphocyte-mediated cell response, which is essential for control of intracerebral replication of the JC virus. Low CSF viral load and a specific cellular immune response in blood and CSF are associated with a better prognosis. Among HIV-infected patients, mortality is greater in those who have CD4+ <100cells/μL.

Numerous drugs have been used empirically or in clinical trials in patients with PML, although none has proven effective. The best option in HIV-infected patients is to initiate ART (AII) or optimize ART (AIII) with potent regimens and good central nervous system (CNS) penetration.31 Prognosis improved with the advent of ART, and survival rates range from 10% per year to 40–75%, although a large percentage of patients present neurological sequelae.32 In patients who experience clinical or radiological deterioration with ART, which is suggestive of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), observational studies suggest prescribing dexamethasone without interrupting ART (BIII).

Influenza virusSeasonal influenza is a frequent cause of respiratory disease in HIV-infected patients. Early studies from the pre-ART era showed that the mortality and complication rates were higher in this population. Studies carried out during the influenza pandemic revealed a greater incidence and more complications in patients with ART or low CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts. However, patients with good virological control who were taking ART had complication rates that were similar to those of the general population.

Early treatment with oseltamivir or zanamivir is recommended in HIV-infected patients suspected of having severe influenza (AI). Prophylaxis with these drugs is recommended in unvaccinated patients with low CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts who have been in close contact with patients with influenza (AI).33 HIV-infected patients should receive the seasonal inactivated influenza vaccine yearly (AI).34

Mycobacterial infectionMycobacterium tuberculosisTreatment of mycobacterial infections in HIV-infected patients is generally the same as in non-HIV-infected patients. As a rule, patients infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis who are sensitive to all drugs should receive isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol (2 months) followed by isoniazid and rifampicin (for a further 4–7 months) (AI). A 6-month course is sufficient for most HIV-infected patients with tuberculosis (TB). The continuation phase should be extended to 7 months if there is a delay in reaching negative values in the sputum culture (>2 months), in patients with a CD4+ T-lymphocyte count <100cells/μL, and in patients whose adherence is questionable (in these cases every attempt should be made to administer therapy directly) (BII). Drugs should be taken daily, as opposed to regimens of 3 or 5 days per week (AI). Fixed-dose combinations should be used (BI). For specific situations, please consult our TB consensus document.35

All HIV-infected patients who develop TB should receive ART, regardless of their CD4+ T-lymphocyte count and viral load, since it reduces the risk of death (AI). The best time to start depends on the CD4+ count. If it is <50cells/μL, ART should be started as soon as possible after verifying tolerance to TB treatment and no later than the first 2 weeks after starting tuberculostatic treatment (AI). If the CD4+ count is >50cells/μL, initiation of ART can be deferred until the intensive phase of TB treatment has been completed (8 weeks). With this approach, the risk of adverse effects and IRIS is reduced without compromising survival (AI).36–38 However, the ideal time to initiate ART in patients whose disease first manifests with tuberculous meningitis remains unknown. Rifampicin interacts with antiretroviral drugs that are metabolized via the CYP3A4 enzyme system. Rifampicin must be included in anti-TB treatment regimens in HIV-infected patients. Therefore, ART should be adjusted to take potential drug interactions into account (Table 4).39

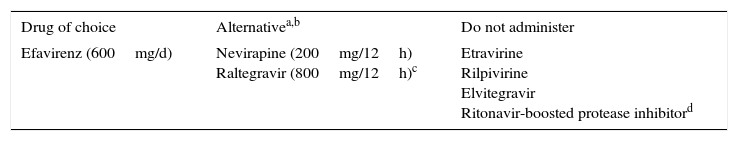

Recommendations for using antiretroviral drugs with rifampicin.a

| Drug of choice | Alternativea,b | Do not administer |

|---|---|---|

| Efavirenz (600mg/d) | Nevirapine (200mg/12h) Raltegravir (800mg/12h)c | Etravirine Rilpivirine Elvitegravir Ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitord |

No interactions have been reported with nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Therefore, all members of the family can be used. The table only shows drugs used as a third agent.

Alternatives with which little clinical experience is available and which are based mainly on pharmacokinetic models include maraviroc (600mg/12h) or dolutegravir (50mg/12h in patients without integrase inhibitor mutations).

As for prevention of TB, all HIV-infected patients should undergo screening for latent TB using the tuberculin skin test or a specific interferon gamma release assay to evaluate the risk of developing TB (AI). Specific testing for cutaneous anergy is not required. The ideal frequency for repeating the tuberculin skin test is unknown in patients whose first result is negative. We suggest that it should always be repeated after confirmed exposure to a patient with active bacilliferous TB and every 2–3 years in all patients with a negative result in the first test (BIII). There are no data to support recommending a prevalence threshold above which the frequency of the tuberculin skin test should be repeated.

Treatment of latent tuberculosis infection is indicated in all patients with a positive tuberculin skin test result (induration of ≥5mm) or who have had a positive result in the past, regardless of the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count, and in whom active disease can reasonably be ruled out (AI).

The regimen of choice continues to be daily isoniazid for 6–9 months (AI). Alternatives include isoniazid (300mg/d)+rifampicin (600mg/d) for 3 months (AII) or rifampicin (600mg/d) for 4 months in cases of toxicity or resistance to isoniazid (BIII). Secondary prophylaxis (maintenance treatment) is not required.

Mycobacterium avium complexTreatment of disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) should be with a combination of drugs. Clinical trials performed during the pre-ART era40,41 showed that a regimen containing clarithromycin (500mg/12h)+ethambutol (15mg/kg/d)±rifabutin (300mg/d) administered over 12 months to reduce resistance is efficacious and the treatment of choice (AI). If rifabutin is used, the dose should be adjusted if the antiretroviral regimen includes a protease inhibitor or efavirenz. The interaction between clarithromycin and efavirenz should be taken into account.

The regimens of choice for preventing disseminated MAC infection are clarithromycin (500mg/12h) or azithromycin (1200mg, once weekly)42,43 (AI). However, this prophylaxis has never been recommended in Spain in severely immunodepressed patients (<100cells/μL) owing to the low incidence of the disease. Primary prophylaxis can be interrupted when patients reach a CD4+ T-lymphocyte count >100cells/μL for a period longer than 3–6 months with antiretroviral therapy (AI). Secondary prophylaxis cannot be used in MAC, and treatment must be maintained until the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count recovers to >100cells/μL (AI).

Other mycobacteriaMycobacteria other than M. tuberculosis and MAC can occasionally cause OIs in HIV-infected patients with different degrees of immunosuppression. No specific recommendations are available for treatment and prevention of these diseases except for those that apply to non-HIV-infected patients with infection by environmental mycobacteria.

Infections caused by other bacteriaRecommendations for the treatment of bacterial respiratory infection caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, less prevalent bacteria (Haemophilus influenzae type b, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Staphylococcus aureus), and unusual bacteria (Nocardia species or Rhodococcus equi) are similar for HIV-infected and non-HIV-infected individuals.6,9 Treatment of intestinal infections caused by Salmonella species, Campylobacter species, or Clostridium difficile is similar to that administered to the general population, except in the case of severely immunodepressed HIV-infected patients, who are at risk of recurrent bacteremia caused by Salmonella species.6,9 The incidence of infections by Bartonella species and Listeria monocytogenes is very low and recommendations for treatment are similar to those of the general population.6,9 Please see Table 5 for the indications for specific treatment.

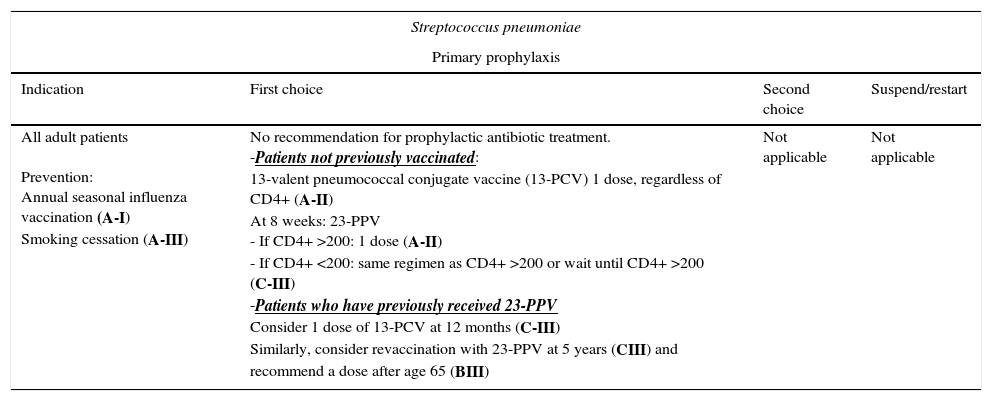

Recommended regimens for prevention and treatment of bacterial infections.

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary prophylaxis | |||

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| All adult patients Prevention: Annual seasonal influenza vaccination (A-I) Smoking cessation (A-III) | No recommendation for prophylactic antibiotic treatment. -Patients not previously vaccinated: 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (13-PCV) 1 dose, regardless of CD4+ (A-II) At 8 weeks: 23-PPV - If CD4+ >200: 1 dose (A-II) - If CD4+ <200: same regimen as CD4+ >200 or wait until CD4+ >200 (C-III) -Patients who have previously received 23-PPV Consider 1 dose of 13-PCV at 12 months (C-III) Similarly, consider revaccination with 23-PPV at 5 years (CIII) and recommend a dose after age 65 (BIII) | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | First choice | Second choice | Remarks |

| Pneumonia Sinusitis | Intermediate resistance and sensitivity: Penicillin G sodium 6–12 MU/d IV (A-II) Amoxicillin 1g/8h po (A-II) Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid 2000/125mg/12h po (A-II) Ceftriaxone 2g/d IV A-II) Resistance Ceftriaxone 2g/d IV (A-II) | Levofloxacin 500mg IV/po (A-II) Vancomycin 1g/12h IV (B-III) | Early initiation of empirical therapy Duration: 7–10 d |

| Secondary prophylaxis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| Does not require suppressive antibiotic therapy (B-III) | |||

| Haemophilus influenzae | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary prophylaxis | |||

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| All adult patients | No recommendation for antibiotic prophylaxis No recommendation for anti- Haemophilus influenzae b vaccine | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | First choice | Second choice | Remarks |

| Pneumonia Sinusitis | Non-betalactamase-producing strain Ampicillin 1–2g/4–6h IV (A-II) Amoxicillin 500mg/8h po (A-II) Betalactamase-producing strain Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid 2000/125mg/12h po (A-II) Ceftriaxone 2g/d IV (A-II) | Levofloxacin 500mg IV/po (A-II) Azithromycin 500mg po (B-III) | Non-typable strains are more common in adults and not covered by the vaccine |

| Secondary prophylaxis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| Does not require suppressive antibiotic therapy (B-III) | |||

ART has proven to be the most effective measure for reducing the incidence of HIV-associated bacterial infections. During 2002–2007, the incidence of invasive infections caused by S. pneumoniae was higher than in the general population, with increased mortality associated with disease severity and the presence of comorbid conditions, especially in patients with liver cirrhosis.9,44

These data supported the recommendation for primary prophylaxis with the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (23-PPV),45 whose efficacy was considered controversial until the extended follow-up of the only randomized clinical trial and results from observational studies suggested a moderate benefit.45,46

The 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (7-PCV) proved highly efficacious in children and had an indirect effect on adults. 7-PCV has been replaced by the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (13-PCV). No data are available on 13-PCV in HIV-infected patients. However, a double-blind randomized trial comparing 7-PCV with placebo performed in patients in Malawi, most of whom had not received ART and who had experienced a previous episode of invasive pneumococcal disease, revealed an efficacy of 75%.47 Other studies revealed a more favorable immunogenic response with a dose of 7-PCV followed by a dose of 23-PPV.45,48

HIV-infected adults who have not been vaccinated should receive a dose of 13-PCV, regardless of their CD4+ T-lymphocyte count (AII). Patients with CD4+ ≥200/μL should subsequently receive a dose of 23-PPV at least 8 weeks after the dose of 13-PCV45,48,49 (AII). In the case of patients with a CD4+ T-lymphocyte count <200cells/μL, the same strategy can be used or the dose of 23-PPV can be deferred until the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count increases to >200cells/μL45,49 (CIII).

The duration of protection with 23-PPV is unknown. In the case of patients who have already received 23-PPV, a dose of 13-PCV can be considered after at least 12 months45,48,49 (CIII). Similarly, revaccination with 23-PPV can be considered after 5 years (CIII), and a dose can be recommended after age 65 years (BIII).45

The annual seasonal influenza vaccination is recommended for prevention of bacterial pneumonia (AI), as is smoking cessation (AIII).9,49

No indications have been proposed for vaccination against H. influenzae type b or N. meningitidis in HIV-infected adults.9,49 Primary antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended against diseases associated with Bartonella species or Listeria monocytogenes.9

Imported parasitic diseasesImmigration, international travel, and more favorable prognosis in HIV-infected persons mean that imported parasitic infections are increasingly common in the HIV-infected population. This section only addresses more severe parasitic diseases or those that act opportunistically in HIV-infected patients.

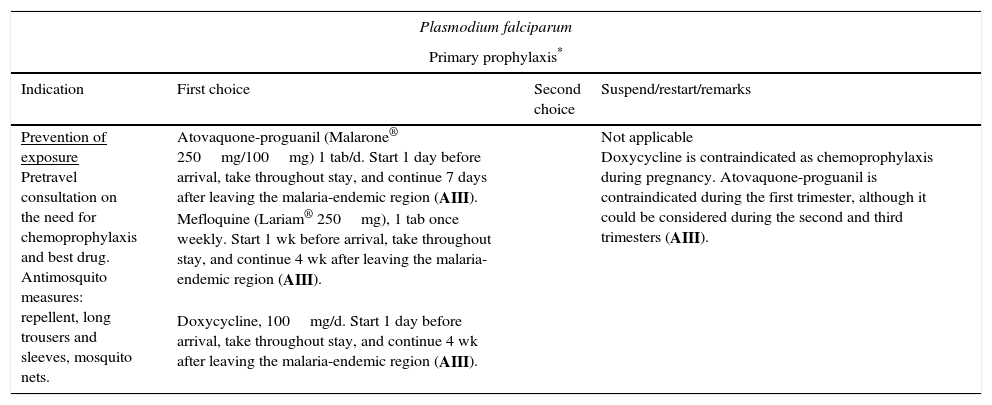

Malaria (especially malaria caused by Plasmodium falciparum) is one of the most relevant infections, since it affects both severely immunodepressed patients and those with normal CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts. Furthermore, a bidirectional negative interaction has been identified between HIV and Plasmodium species.50 Undoubtedly, the population most at risk of infection by Plasmodium species in our setting is that formed by immigrants who travel to their home country without having received chemoprophylaxis. Malaria is a key cause of fever in travelers who return from tropical countries, especially if they are from Sub-Saharan Africa. Given that the patient's condition can deteriorate rapidly (in only a few hours), a high level of diagnostic suspicion and early treatment are necessary. The indications for treatment are the same as for non-HIV-infected persons (Table 6).51 Close monitoring is recommended, especially in patients with low CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts, since the clinical manifestations in this group are usually more severe. Please consult potential interactions between antimalarial and antiretroviral drugs when considering treatment and chemoprophylaxis (www.interaccionesvih.com;http://www.hiv-druginteractions.org).52

Recommended regimens for the prevention and treatment of imported parasitic diseases.

| Plasmodium falciparum | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary prophylaxis* | |||

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart/remarks |

| Prevention of exposure Pretravel consultation on the need for chemoprophylaxis and best drug. Antimosquito measures: repellent, long trousers and sleeves, mosquito nets. | Atovaquone-proguanil (Malarone® 250mg/100mg) 1 tab/d. Start 1 day before arrival, take throughout stay, and continue 7 days after leaving the malaria-endemic region (AIII). Mefloquine (Lariam® 250mg), 1 tab once weekly. Start 1 wk before arrival, take throughout stay, and continue 4 wk after leaving the malaria-endemic region (AIII). Doxycycline, 100mg/d. Start 1 day before arrival, take throughout stay, and continue 4 wk after leaving the malaria-endemic region (AIII). | Not applicable Doxycycline is contraindicated as chemoprophylaxis during pregnancy. Atovaquone-proguanil is contraindicated during the first trimester, although it could be considered during the second and third trimesters (AIII). | |

| Treatment* | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| First choice | Second choice | Remarks | |

| Nonsevere malaria | Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine (Eurartesim® 40mg/320mg) <75kg, 3 tab/d×3 d (total of 9 tabs) 75–100kg, 4 tab/d×3 d (total of 12 tabs), or Atovaquone-proguanil (Malarone® 250mg/100mg) 4 tabs/d×3 d (total of 12 tabs), or Artemether-lumefantrine (Riamet® or Coartem® 20mg/120mg) 4 tabs at 0, 8, 24, 36, 48, and 60h (total of 24 tabs) (AIII) | Quinine sulfate (300–325mg tab) 2 tabs/8h+doxycycline 100mg/12h×7 d (total of 56 tabs) (AIII) | Artemisinin derivatives are contraindicated during the first trimester. In these cases, quinine sulfate should be administered (300–325mg tab) as 2 tabs/8h+oral clindamycin 450mg/8h for 7 d. |

| Severe malaria | Artesunate 2.4mg/kg IV. Repeat dose at 12h, 24h, and every 24h until oral treatment can be started. It should be administered for at least 24h (3 doses). Sequential treatment should also be administered after IV artesunate (AIII) | Quinine 20mg/kg IV as the initial dose in dextrose solution over 4h, followed by 10mg/kg over 4h every 8h (maximum 1800mg/d) associated with clindamycin 10mg/kg/12h IV or doxycycline 100mg/12h for 7 d. The patients should be monitored for hypoglycemia and heart arrhythmias when quinine is administered intravenously. Do not administer loading dose and start with 10mg/kg if the patient has been exposed to chloroquine, oral quinine, or mefloquine (AIII). | Artemisinin derivatives are contraindicated during the first trimester (although the risk-benefit ratio should be evaluated in very severe cases). Quinine IV combined with clindamycin IV should be used in the first trimester. |

| P. vivax, P. ovale, P. malariae, and P. knowlesi | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary prophylaxis* | |||

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| Prevention of exposure: As in P. falciparum | Oral chloroquine (Resochin® o Dolquine® 155mg base), 2 tabs once weekly. Start 1 wk before arrival, administer during the stay, and continue 4 wk after leaving the malaria-endemic region (AIII). Atovaquone-proguanil (Malarone® 250mg/100mg) or mefloquine (Lariam® 250mg) at the same doses and in the same regimens as for prevention of P falciparum (AIII). | Not applicable Doxycycline is contraindicated as chemoprophylaxis during pregnancy. Atovaquone-proguanil is contraindicated during the first trimester, although it could be considered during the second and third trimesters (AIII). | |

| Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | First choice | Second choice | Remarks |

| Nonsevere malaria | Oral chloroquine (Resochin® o Dolquine® 155mg base) at an initial dose of 4 tabs followed by 2 tabs at 6, 24, and 48h (4+2+2+2=10 tabs) If P. vivax, add primaquine (Primaquine® 7.5mg base) 30mg base=4 tabs/d×2 wk Si P. ovale, add primaquine (Primaquine® 7.5mg base) 15mg base=2 tabs/d×2 wk (AII) | Artemether-lumefantrine (Riamet® or Coartem® 20mg/120mg) 4 tabs at 0, 8, 24, 36, 48, and 60h (total 24 tabs) | Primaquine can cause severe hemolytic anemia in persons with G6PDH deficiency. It is contraindicated during pregnancy owing to the risk of hemolytic anemia in the fetus. Oral chloroquine should be given in 2 tabs (300mg)/wk until delivery in order to prevent relapse. |

| Trypanosoma cruzi (Chagas disease) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary prophylaxis | |||

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| Prevention of exposure: Avoid vector stings/bites and consumption of potentially contaminated juices in endemic areas. Transmission via blood transfusion is possible but rare (AIII) | - Early ART prevents severe immunodepression and reduces the risk of reactivation | Not applicable | |

| Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | First choice | Second choice | Remarks |

| Treat acute infections, chronic infections (especially recent infections) if no contraindications or advanced heart disease, and reactivations. Reactivations affect patients with a CD4+ T-lymphocyte count <200cells/μL (especially <100cells/μL) | Benznidazole 5–8mg/kg/d po divided into 2 doses for 60 d (AIII) | Nifurtimox 8–10mg/kg/d po divided into 2–3 doses for 60–90 d (AIII) | Start antiretroviral therapy early in reactivations. Benznidazole and nifurtimox are contraindicated during pregnancy, except for reactivations, in which case it is necessary to evaluate the risk of a disease that can place the mother's life in danger against the theoretical risk of fetal malformations. Both drugs should be used with caution in patients with kidney or liver failure. |

| Secondary prophylaxis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| After a reactivation | Early initiation and maintenance of ART Benznidazole 5mg/kg/d for 3 d/wk or 200mg/d (CIII) | Suspend when the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count reaches 200–250cells/μL and viral load is undetectable for at least 6 months | |

| Strongyloides stercoralis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary prophylaxis | |||

| Indication | First choice | Second choice | Suspend/restart |

| Prevention of exposure: Avoid walking barefoot or allowing skin to come into contact with potentially contaminated surfaces in order to prevent contact with infective filariform larvae. | Not applicable | Not applicable | |

| Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | First choice | Second choice | Remarks |

| Acute and chronic strongyloidiasis | Ivermectin 200μg/kg/d po in a single dose. Repeat the dose after 1 wk or 2 wk. In the case of hyperinfestation syndrome or disseminated strongyloidosis, administer a daily dose of ivermectin until stool and/or sputum samples are negative (AIII). | Albendazole 400mg twice daily for 7 d po (BIII) | Treat early if strongyloidosis is suspected or confirmed, especially if antiretroviral therapy has not been initiated (CIII) |

Before prescribing, consult potential interactions between the antiparasitic drugs selected and antiretroviral drugs (www.interaccionesvih.com;http://www.hiv-druginteractions.org).

Acute Trypanosoma cruzi infection is almost exclusive to endemic areas (from the south of the United States of America to the north of Chile and Argentina). It is often asymptomatic and, if not treated, can progress to chronic disease. Approximately 20–40% of patients develop visceral involvement (mainly the heart). In Europe, the most common form of transmission is vertical transmission (5% risk); infection associated with transfusions or organ transplantation has been reported only exceptionally. In HIV-infected patients with chronic T. cruzi infection, this protozoan disease behaves like an OI; therefore, patients from an endemic area should be screened (AIII).53 Reactivations usually affect patients with CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts <200cells/μL, especially when counts fall to below 100cells/μL. At this level of immunodepression, Chagas disease more commonly affects the central nervous system (in the form of space occupying lesions [chagomas] or meningoencephalitis), followed by the heart (mainly myocarditis). Cardiac involvement during a reactivation is sometimes difficult to distinguish from heart disease in a chronically infected patient. Diagnosis of chronic disease is based on serology findings, whereas diagnosis of reactivations is essentially based on direct parasitology (blood, CSF, or other body fluids) or histopathology. Benznidazole is the first choice for treatment, followed by nifurtimox, with which less experience is available (AIII) (Table 6). Duration, dose, interactions, and need for secondary prophylaxis have yet to be resolved.52,53 Posaconazole has not proven useful for this indication.54 The scarce data available on the effect of early initiation of ART does not seem to indicate the involvement of immune reconstitution phenomena in the CNS. Therefore, and given the high morbidity and mortality of reactivations, early initiation of ART is recommended (AIII).

Strongyloidiasis is a helminth infestation that can become chronic owing to an autoinfection cycle; therefore, it should be suspected even many years after the patient has resided in or traveled to an endemic area. The most severe form is hyperinfection syndrome, which is more common in persons treated with corticosteroids or coinfected by HTLV-1.55 However, in HIV-infected patients, this clinical presentation is very unusual and is observed more as IRIS (when the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count recovers) than a condition associated with severe immunodepression.56,57 Treatment is summarized in Table 6.

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndromeIRIS is caused by restoration of the cellular inflammatory response in very immunodepressed patients who initiate ART.58 It has 2 manifestations: unmasking IRIS, which reveals a pre-existing occult OI, and paradoxical IRIS, which involves clinical deterioration of a previously diagnosed OI that has been treated appropriately.59

Diagnosis is by exclusion, that is, ruling out other possible causes of worsening after initiating ART, such as drug-induced toxicity, failure of ART, failure of antimicrobial therapy, or the presence of intercurrent diseases.

The severity of symptoms should be evaluated to determine the need for treatment and the risk-benefit ratio of potential interventions.60 The objectives of treatment are to minimize morbidity and mortality and sequelae, improve symptoms, and reduce disease duration. Corticosteroids are the treatment of choice and are used mainly in IRIS caused by mycobacteria and fungi; their use is controversial in viral infections, and they are contraindicated in Kaposi sarcoma. The only randomized trial available61 compared prednisone (1.5mg/kg/d for 2 weeks and 0.75mg/kg/d for a further 2 weeks) blind with placebo in patients with TB or IRIS. In patients whose condition worsened, prednisone was added open-label. Prednisone reduced the duration of hospitalization and symptoms, with no differences in mortality. Some patients required a longer course of treatment. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can prove useful in patients with mild symptoms.62 Other drugs (IL-2, GM-CSF, infliximab, and maraviroc) are considered experimental. Patients with lymph node abscess may require repeated aspiration or surgical drainage. Lastly, it is important to remember that antimicrobial treatment must be optimized when possible and that it is not recommended to suspend ART.

Our observations for IRIS can be summarized as follows: (a) In the presence of IRIS, neither ART nor antimicrobial therapy can be suspended; (b) Mild forms of IRIS can improve with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (B-III); and (c) Corticosteroids are recommended for treatment of IRIS in patients with moderate-severe manifestations associated with mycobacteria and CNS involvement (A-II).

Conflict of interestThese authors and reviewers have not received any aid or grant related to this document.

Coordinators: José Antonio Iribarren and Rafael Rubio.

Parasitic infections. Authors: José Ma Miró, José Sanz Moreno. Reviewers: Jaime Locutura, José López Aldeguer, Eduardo Malmierca, Pilar Miralles, Esteban Ribera.

Fungal infections. Authors: Josu Baraia Etxaburu, Juan Carlos López Bernaldo de Quirós. Reviewers: Pere Domingo, Fernando Lozano, Eulalia Valencia, Francisco Rodríguez Arrondo, Ma Jesús Téllez.

Mycobacterial infections. Authors: Santiago Moreno, Antonio Rivero. Reviewers: Joan Caylá, Vicente Estrada, Celia Miralles, Inés Pérez, Miguel Santín.

Viral infections. Authors: Daniel Podzamczer, Melchor Riera. Reviewers: Concha Amador, Antonio Antela, Julio Arrizabalaga, Juan Berenguer, Josep Mallolas.

Bacterial infections. Authors: Koldo Aguirrebengoa, Juan Emilio Losa. Reviewers: Pablo Bachiller, Carlos Barros, Hernando Knobel, Miguel Torralba, Miguel Angel Von Wichmann.

Prevention and treatment of imported diseases. Authors: Félix Gutiérrez, José Pérez Molina. Reviewers: Agustín Muñoz, Julián Olalla, José Luis Pérez Arellano, Joaquín Portilla.

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Authors: José Ramón Arribas, Federico Pulido. Reviewers: Piedad Arazo, Josep Ma Llibre, Antonio Ocampo, Ma Jesús Pérez Elías, Jesús Sanz Sanz.

See Appendix A for the contributions of the Authors and Reviewers.

Readers who prefers to have this review in Castilian, can be obtained from the following address: http://www.gesida-seimc.org/contenidos/guiasclinicas/2015/gesida-guiasclinicas-2015-InfeccionesOportunistasyCoinfeccionesVIH.pdf.