To describe the clinical features, history and association with intestinal disease in central nervous system (CNS) S. bovis infections.

MethodsFour cases of S. bovis CNS infections from our institution are presented. Additionally a systematic literature review of articles published between 1975 and 2021 in PubMed/MEDLINE was conducted.

Results52 studies with 65 cases were found; five were excluded because of incomplete data. In total 64 cases were analyzed including our four cases: 55 with meningitis and 9 with intracranial focal infections. Both infections were frequently associated with underlying conditions (70.3%) such as immunosuppression (32.8%) or cancer (10.9%). In 23 cases a biotype was identified, with biotype II being the most frequent (69.6%) and S. pasteurianus the most common within this subgroup. Intestinal diseases were found in 60.9% of cases, most commonly neoplasms (41.0%) and Strongyloides infestation (30.8%). Overall mortality was 17.1%, with a higher rate in focal infection (44.4% vs 12.7%; p=0.001).

ConclusionsCNS infections due to S. bovis are infrequent and the most common clinical form is meningitis. Compared with focal infections, meningitis had a more acute course, was less associated with endocarditis and had a lower mortality. Immunosuppression and intestinal disease were frequent in both infections.

Streptococcus bovis, una causa bien conocida de endocarditis asociada a cáncer colorrectal, es también una causa poco frecuente de infecciones del sistema nervioso central (SNC), incluyendo meningitis, abscesos cerebrales o empiema subdural. El objetivo de este estudio es describir las características clínicas, los antecedentes médicos y la asociación con la enfermedad intestinal en las infecciones por S. bovis en el SNC.

MétodosDescribimos 4 infecciones por S. bovis en el SNC en nuestra Unidad y, a continuación, presentamos una revisión bibliográfica de los artículos publicados entre 1975-2021 en PubMed/MEDLINE.

ResultadosSe encontraron 52 estudios con 65 casos; 5 se excluyeron por datos incompletos. En total se analizaron 64 casos incluyendo nuestros 4: 55 con meningitis y 9 con infecciones focales intracraneales. Ambas infecciones se asociaron con frecuencia a condiciones subyacentes (70,3%) como la inmunosupresión (32,8%) o el cáncer (10,9%). En 23 casos se identificó un biotipo, siendo el más frecuente el biotipo ii (69,6%), y dentro de ellos, S. pasteurianus. En el 60,9% de los casos se detectaron enfermedades intestinales, siendo las más frecuentes las neoplasias (41,0%) y la infestación por Strongyloides (30,8%). La mortalidad global fue del 17,1%, con una tasa mayor en la infección focal (44,4 frente a 12,7%; p=0,001).

ConclusionesLas infecciones del SNC debidas a S. bovis son poco frecuentes y la forma clínica más común es la meningitis. En comparación con las infecciones focales, la meningitis tiene un curso más agudo, está menos asociada a la endocarditis y tiene una menor mortalidad. La inmunosupresión y la enfermedad intestinal fueron frecuentes en ambas infecciones.

Streptococcus bovis, currently named Streptococcus bovis/equinus complex,1 is a gram-positive bacterium and a part of the intestinal microbiota of healthy humans. Streptococcus bovis is a frequent endocarditis cause, being associated with colorectal carcinoma in a high rate.2Streptococcus bovis is an infrequent but known cause of meningitis in children3 and is rarer in adults. In a non-S. pneumoniae streptococcal meningitis series, S. bovis caused 5% of the cases.4 Other types of central nervous system (CNS) infections, like intracranial focal infections are less common; a few cases of brain abscesses and subdural empyema have been reported.5–11 These cases are occasionally associated with colorectal carcinoma.5,7

Due to its low incidence, the clinical manifestations and management of S. bovis CNS infections are not fully characterized, neither are their related conditions. For example, S. bovis infective endocarditis, mainly S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus, is associated with colorectal cancer, but whether this cancer associates also with CNS infections remains unknown.

The objective of the present study is to describe the clinical features and natural history of CNS infections caused by S. bovis and their degree of association with intestinal disease.

MethodsPatients326 S. bovis bacteremia episodes were identified between 1990 and 2021 in our hospital. In two cases a concurrent CNS infection was demonstrated: one case of meningitis and one case of brain abscess. During the same period 532 positive isolates for S. bovis other than blood cultures were identified; from which one case was a pus sample from a subdural empyema and one case was a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) culture from a patient with meningitis. This four case-series patients was extended with a systematic literature research.

Microbiological methodsSpecies identification of both strains was performed using the API 20 STREP and VITEK 2 systems using the Gram-positive (GP) identification card (both from bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). Additional confirmatory tests were performed by conventional12 and molecular methods by analysis of the complete rRNA gene sequence,13 as well as the polymorphism of manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase gene (sodA) according to the indications of Poyart et al.14 The sequences obtained were compared with those of the corresponding genes available in GenBank by using Blast sequence software (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of penicillin and cefotaxime was determined by E-test (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) on Mueller-Hinton agar plates supplemented with 5% sheep blood.

Literature reviewTo identify additional cases of S. bovis CNS infections in adults, we conducted a limited search in Pubmed/Medline in July 2021. Articles published since 1975 to 30 July 2021 were included. The search terms used were [Streptococcus bovis OR gallolyticus OR pasteurianus OR infantarius] AND [meningitis OR brain OR spinal OR subdural OR “epidural abscess”]. Secondarily, references in the retrieved articles were also reviewed. All articles were screened for the following information: age, sex, type of CNS infection and other concomitant infections, systemic and neurological symptoms, diagnostic methods, S. bovis biotypes or subspecies if available, type of intestinal lesion where present, comorbidities, treatment and outcome. The absence of this information except the biotype conduced to the exclusion the articles. Epidural abscesses were also excluded because they are almost invariably secondary to spondylodiscitis.15 All the information was codified in a separate database.

Statistical analysis and report of the resultsQuantitative variables were expressed in mean and standard deviation; categorical variables with counts and percentages. Chi squared test was used when testing categorical variables between groups.

ResultsCase reportCase 1. Cerebral abscessA 61-year-old male farmer who has contact with cattle and with no previous significant medical problems presented with a week history of malaise, headache, fever and progressive weakness of the left arm. The physical examination revealed an afebrile patient with normal vital signs. He was alert and exhibited normal mental activity. The patient had hypoesthesia and paresis in his left arm. Meningeal signs were negative. The rest of the physical findings were unremarkable.

The results of the laboratory studies performed at admission were unremarkable (leukocyte count of 8000/mm3 and 65mg/L C-reactive protein). A contrast-enhanced CT of the head revealed a loculated ring-enhancing lesion of 2cm in the right parietal lobe. The blood cultures yielded S. bovis. The isolate was identified as S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus (S. bovis biotype I). The MICs for penicillin and cefotaxime were 0.064 and 0.19mg/L respectively. Therapy with ceftriaxone 2g every 12h was initiated. The patient improved during the first 24h. An echocardiogram revealed mitral and aortic valve vegetations, without valvular regurgitations. A colonoscopy showed diverticula and a 1cm tubular adenoma in the descending colon and 2 tubular microadenomas in the hepatic flexure. After a total of 8 weeks of antibiotic therapy, the patient fully recovered all neurological function. A total follow-up of five years was completed without signs of recurrence.

Case 2. Subdural empyemaA 72-year-old male farmer who has contact with cattle was admitted to our hospital with a two-day course of fever and delirium. The patient had a history of insulin-treated diabetes, chronic lymphocytic leukemia and an aortic valve prosthesis implanted 22 months before. One month before this hospitalization, the patient was admitted with a spontaneous chronic right occipital subdural hematoma, and trepanation was conducted. The patient fully recovered.

During the second hospitalization, the physical examination revealed bradypsychia, disorientation and fever (38.5°C), with no neurological deficit. Amoxicillin-clavulanate 1g every 8h was initiated at the Emergency Department for a putative urinary tract infection, although no urinary symptoms were reported. The results of the laboratory studies and chest radiograph were normal. Blood cultures and urine cultures collected after 2 antibiotic doses were negative.

At the fifth day of hospitalization, the patient complained of headache, experienced epileptic seizures and developed left hemiparesis. A brain CT scan revealed enlargement of the previously known subdural hematoma with peripheral areas of rebleeding with edema and midline deviation. The patient underwent craniotomy, during which pus was observed, and an empyema evacuation was performed. Streptococcus bovis was isolated in the sample submitted to Microbiology. The isolate was identified as S.infantarius subsp. coli (S. bovis biotype II/1). The MICs for penicillin and cefotaxime were 0.032mg/L and 0.064mg/L, respectively.

The study was completed with a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE), which revealed a vegetation on the prosthetic valve, without valvular insufficiency. Treatment was completed with ceftriaxone 2g every 12h for 6 weeks, with favorable clinical and radiological evolution and resolution of the condition, as well as resolution of the vegetation in the TEE. For this reason, no valvular surgery was needed. A colonoscopy performed 16 months earlier was normal. He continued to be alive and well during a three-year follow-up.

Case 3. Acute meningitis with endocarditisAn 80-year-old man with a history of diabetes mellitus and chronic lymphocytic leukemia in progression was awaiting for chemotherapy initiation. He consulted at the Emergency Department with fever (39°C), chills and stupor. Physical examination reveal stupor and neck stiffness with no focal neurogical deficit. Blood test results were unremarkable. A head CT scan showed no anomalies and lumbar puncture was performed. CSF analysis showed glychorrhachia of 65mg/dL (plasmatic 132mg/dL), proteinorrhachia of 358mg/dL and neutrophil predominant pleocytosis (732cells per mm3, 98%). Therapy with meropenem 2g every 8h, linezolid 600mg every 12h and ampicillin 2g every 4h was initiated and he was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit. After antimicrobial were instated fever submitted and neurological status improved during the following 48h, allowing for his discharge to a conventional ward. Blood and CSF culture yielded S. bovis, thus therapy was modified to ceftriaxone 2g every 12h. The isolate was identified as S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus (S. bovis biotype II/2), MICs for penicillin was 0.064 and for cefotaxime were 0.125mg/L. A TEE was performed showing severe mitral regurgitation with tendinous string break-up and a vegetation. After the patient was stabilized, he underwent a colonoscopy which showed diverticula with no other abnormalities. A total of 4-week ceftriaxone therapy was completed. Patient died 25 months after due to progression of his hematological disease.

Case 4. Acute meningitis with spondylodiscitisAn 86-year-old man with medical history of valvular cardiopathy secondary to severe mitral regurgitation, expecting surgery decision, and a chronic subdural hematoma 9 years before with symptomatic epileptic seizures. He had contact with cattle.

He consulted to Emergency Department with decreased consciousness level since 5h before. He had fever of 38.9C with no other vital sign affected. Physical examination revealed stupor, neck stiffness and no focal neurological deficit. A head CT scan was performed which was normal, and a lumbar puncture was made. CSF was turbid, with hypoglychorrhachia (47mg/dL, plasmatic 139mg/dL), hyperproteinorrhachia (435mg/dL) and neutrophil predominant pleocytosis (5800cells per mm3, 87%). Ceftriaxone, ampicillin and vancomycin were initiated and the patient was admitted into hospitalization. He showed sensorium improvement but disorientation and neck pain remained, so a brain and spine MNR scan were performed. Meningeal contrast enhancement and cervical spondylodiscitis were found but no abscesses nor meningeal space invasion. Streptococcus bovis was isolated in blood cultures but not in CSF culture. The isolate was identified as S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus (S. bovis biotype I), MICs for penicillin was 0.094 and for cefotaxime was 0.190mg/L. Therapy was simplified to ceftriaxone 4gr per day for 6 weeks. Two successive TEE performed ten days apart revealed no vegetation. Colonoscopy was undertaken showing diverticulosis. Over the following two weeks, the patients showed progressive recovery and was finally discharged without any sequels. Four months later he was admitted with community acquired pneumonia and died of complications.

Literature reviewSearch resultsFifty-two studies were found including a total of 65 cases. All studies were cases report. Five cases were excluded because of incomplete data. 60 cases were included,5–11,16–56 in addition to our 4 patients. A total of 64 cases were analyzed, 55 of which were meningitis and 9 were intracranial focal infections.

Clinical findings- -

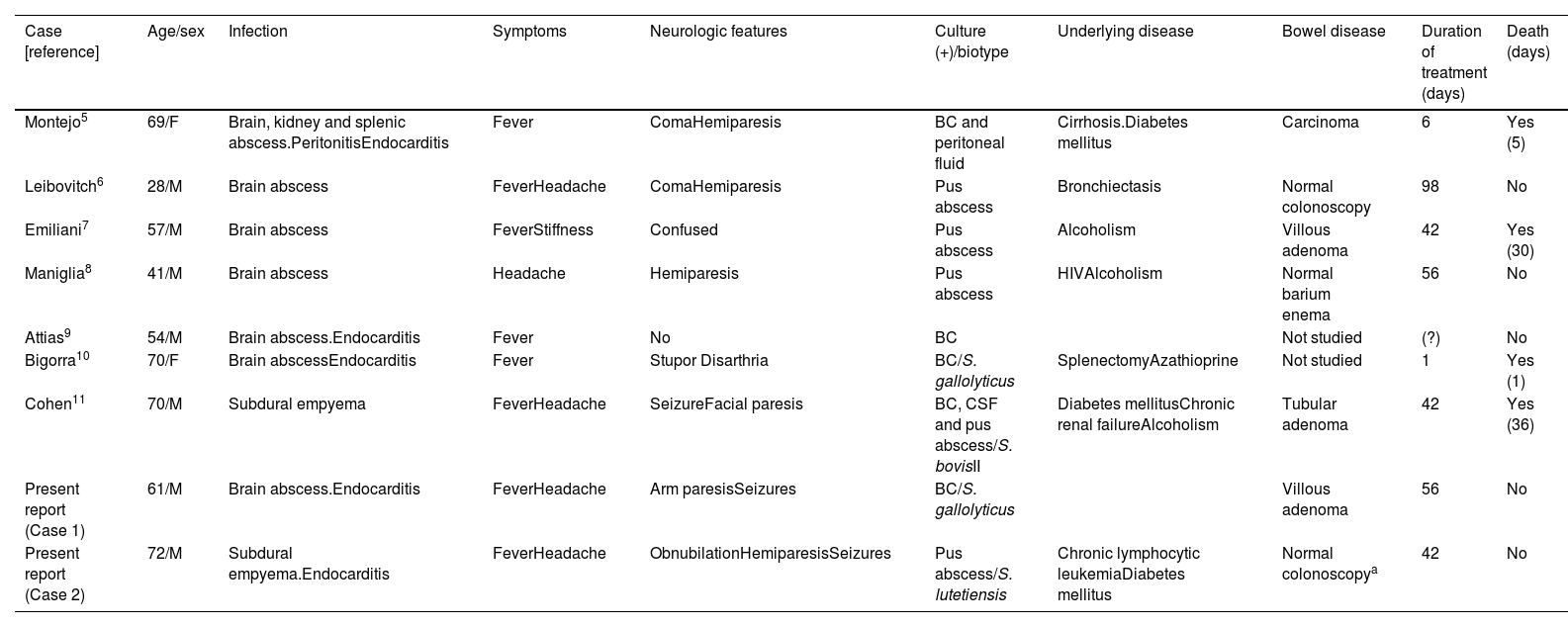

Intracranialfocal infections: 9 patients were included, 7 cases of brain abscesses and 2 subdural empyemas. Mean age was 57.8±15.0 years and the male to female ratio was 3.5:1. Fever was present in 8 (88.8%), headache in 5 (55.5%), focal neurological deficit in 7 (77.7%) and stupor or coma in 3 (33.3%). Patients’ characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.Central nervous system abscess caused by Streptococcus bovis in adults. Literature review and two report cases.

Case [reference] Age/sex Infection Symptoms Neurologic features Culture (+)/biotype Underlying disease Bowel disease Duration of treatment (days) Death (days) Montejo5 69/F Brain, kidney and splenic abscess.PeritonitisEndocarditis Fever ComaHemiparesis BC and peritoneal fluid Cirrhosis.Diabetes mellitus Carcinoma 6 Yes (5) Leibovitch6 28/M Brain abscess FeverHeadache ComaHemiparesis Pus abscess Bronchiectasis Normal colonoscopy 98 No Emiliani7 57/M Brain abscess FeverStiffness Confused Pus abscess Alcoholism Villous adenoma 42 Yes (30) Maniglia8 41/M Brain abscess Headache Hemiparesis Pus abscess HIVAlcoholism Normal barium enema 56 No Attias9 54/M Brain abscess.Endocarditis Fever No BC Not studied (?) No Bigorra10 70/F Brain abscessEndocarditis Fever Stupor Disarthria BC/S. gallolyticus SplenectomyAzathioprine Not studied 1 Yes (1) Cohen11 70/M Subdural empyema FeverHeadache SeizureFacial paresis BC, CSF and pus abscess/S. bovisII Diabetes mellitusChronic renal failureAlcoholism Tubular adenoma 42 Yes (36) Present report (Case 1) 61/M Brain abscess.Endocarditis FeverHeadache Arm paresisSeizures BC/S. gallolyticus Villous adenoma 56 No Present report (Case 2) 72/M Subdural empyema.Endocarditis FeverHeadache ObnubilationHemiparesisSeizures Pus abscess/S. lutetiensis Chronic lymphocytic leukemiaDiabetes mellitus Normal colonoscopya 42 No F: female; M: male; BC: blood culture; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus.

- -

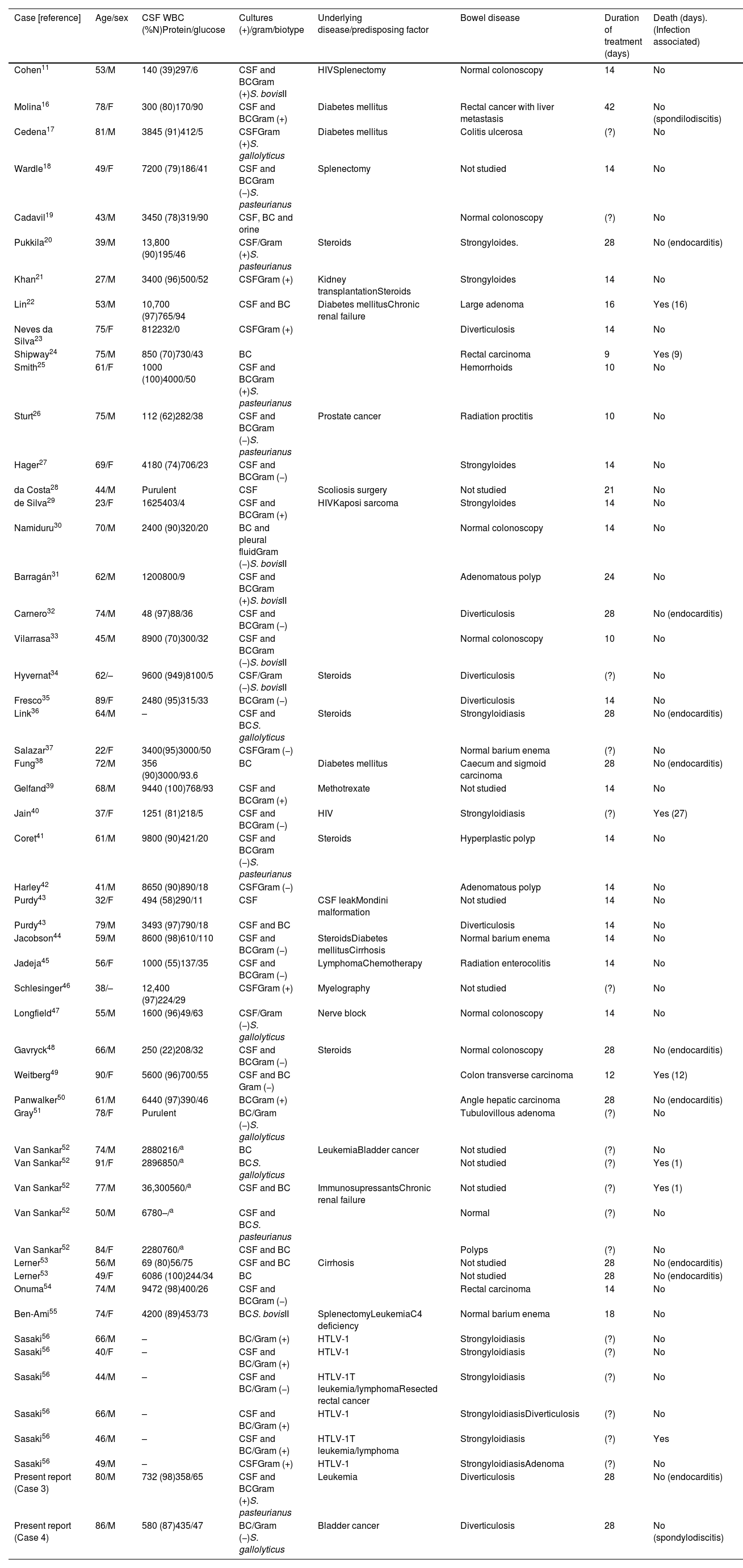

Meningitis: 55 patients were included. Mean age was 60.6±17.6 years and the sex ratio (men/women) was 1.9:1. In 15 of the 30 (50%) patients in which the symptom duration was recorded, symptoms lasted less than 24h; eight patients (26.6%) had a symptoms duration of more than three days. In 48 cases in which the symptoms were collected, fever was present in 40 (83.3%), headache in 29 (60.4%), neck stiffness in 38 (79.1%), and 2 had shock. Focal neurological deficit was observed in 6 patients (12.5%), coma in 4 (8.3%) and seizures in 2. Nine patients had associated endocarditis (16.4%) and 3 spondylodiscitis (5.4%); one of these patients had both endocarditis and spondylodiscitis. Association with endocarditis was higher in intracranial focal infections than meningitis (55.5% vs 16.4%, p=0.019). CSF abnormalities were typical of bacterial meningitis (Tables 2 and 3), and only 12 of 46 (26%) in which CSF results were reported had less than 1000cells/mm3. The features of our 2 cases of meningitis and the 53 previously reported cases of S. bovis CNS infection are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.Meningitis caused by Streptococcus bovis in adults. Literature review and two report cases.

Case [reference] Age/sex CSF WBC (%N)Protein/glucose Cultures (+)/gram/biotype Underlying disease/predisposing factor Bowel disease Duration of treatment (days) Death (days). (Infection associated) Cohen11 53/M 140 (39)297/6 CSF and BCGram (+)S. bovisII HIVSplenectomy Normal colonoscopy 14 No Molina16 78/F 300 (80)170/90 CSF and BCGram (+) Diabetes mellitus Rectal cancer with liver metastasis 42 No (spondilodiscitis) Cedena17 81/M 3845 (91)412/5 CSFGram (+)S. gallolyticus Diabetes mellitus Colitis ulcerosa (?) No Wardle18 49/F 7200 (79)186/41 CSF and BCGram (−)S. pasteurianus Splenectomy Not studied 14 No Cadavil19 43/M 3450 (78)319/90 CSF, BC and orine Normal colonoscopy (?) No Pukkila20 39/M 13,800 (90)195/46 CSF/Gram (+)S. pasteurianus Steroids Strongyloides. 28 No (endocarditis) Khan21 27/M 3400 (96)500/52 CSFGram (+) Kidney transplantationSteroids Strongyloides 14 No Lin22 53/M 10,700 (97)765/94 CSF and BC Diabetes mellitusChronic renal failure Large adenoma 16 Yes (16) Neves da Silva23 75/F 812232/0 CSFGram (+) Diverticulosis 14 No Shipway24 75/M 850 (70)730/43 BC Rectal carcinoma 9 Yes (9) Smith25 61/F 1000 (100)4000/50 CSF and BCGram (+)S. pasteurianus Hemorrhoids 10 No Sturt26 75/M 112 (62)282/38 CSF and BCGram (−)S. pasteurianus Prostate cancer Radiation proctitis 10 No Hager27 69/F 4180 (74)706/23 CSF and BCGram (−) Strongyloides 14 No da Costa28 44/M Purulent CSF Scoliosis surgery Not studied 21 No de Silva29 23/F 1625403/4 CSF and BCGram (+) HIVKaposi sarcoma Strongyloides 14 No Namiduru30 70/M 2400 (90)320/20 BC and pleural fluidGram (−)S. bovisII Normal colonoscopy 14 No Barragán31 62/M 1200800/9 CSF and BCGram (+)S. bovisII Adenomatous polyp 24 No Carnero32 74/M 48 (97)88/36 CSF and BCGram (−) Diverticulosis 28 No (endocarditis) Vilarrasa33 45/M 8900 (70)300/32 CSF and BCGram (−)S. bovisII Normal colonoscopy 10 No Hyvernat34 62/– 9600 (949)8100/5 CSF/Gram (−)S. bovisII Steroids Diverticulosis (?) No Fresco35 89/F 2480 (95)315/33 BCGram (−) Diverticulosis 14 No Link36 64/M – CSF and BCS. gallolyticus Steroids Strongyloidiasis 28 No (endocarditis) Salazar37 22/F 3400(95)3000/50 CSFGram (−) Normal barium enema (?) No Fung38 72/M 356 (90)3000/93.6 BC Diabetes mellitus Caecum and sigmoid carcinoma 28 No (endocarditis) Gelfand39 68/M 9440 (100)768/93 CSF and BCGram (+) Methotrexate Not studied 14 No Jain40 37/F 1251 (81)218/5 CSF and BCGram (−) HIV Strongyloidiasis (?) Yes (27) Coret41 61/M 9800 (90)421/20 CSF and BCGram (−)S. pasteurianus Steroids Hyperplastic polyp 14 No Harley42 41/M 8650 (90)890/18 CSFGram (−) Adenomatous polyp 14 No Purdy43 32/F 494 (58)290/11 CSF CSF leakMondini malformation Not studied 14 No Purdy43 79/M 3493 (97)790/18 CSF and BC Diverticulosis 14 No Jacobson44 59/M 8600 (98)610/110 CSF and BCGram (−) SteroidsDiabetes mellitusCirrhosis Normal barium enema 14 No Jadeja45 56/F 1000 (55)137/35 CSF and BCGram (−) LymphomaChemotherapy Radiation enterocolitis 14 No Schlesinger46 38/– 12,400 (97)224/29 CSFGram (+) Myelography Not studied (?) No Longfield47 55/M 1600 (96)49/63 CSF/Gram (−)S. gallolyticus Nerve block Normal colonoscopy 14 No Gavryck48 66/M 250 (22)208/32 CSF and BCGram (−) Steroids Normal colonoscopy 28 No (endocarditis) Weitberg49 90/F 5600 (96)700/55 CSF and BC Gram (−) Colon transverse carcinoma 12 Yes (12) Panwalker50 61/M 6440 (97)390/46 BCGram (+) Angle hepatic carcinoma 28 No (endocarditis) Gray51 78/F Purulent BC/Gram (−)S. gallolyticus Tubulovillous adenoma (?) No Van Sankar52 74/M 2880216/a BC LeukemiaBladder cancer Not studied (?) No Van Sankar52 91/F 2896850/a BCS. gallolyticus Not studied (?) Yes (1) Van Sankar52 77/M 36,300560/a CSF and BC ImmunosupressantsChronic renal failure Not studied (?) Yes (1) Van Sankar52 50/M 6780–/a CSF and BCS. pasteurianus Normal (?) No Van Sankar52 84/F 2280760/a CSF and BC Polyps (?) No Lerner53 56/M 69 (80)56/75 CSF and BC Cirrhosis Not studied 28 No (endocarditis) Lerner53 49/F 6086 (100)244/34 BC Not studied 28 No (endocarditis) Onuma54 74/M 9472 (98)400/26 CSF and BCGram (−) Rectal carcinoma 14 No Ben-Ami55 74/F 4200 (89)453/73 BCS. bovisII SplenectomyLeukemiaC4 deficiency Normal barium enema 18 No Sasaki56 66/M – BC/Gram (+) HTLV-1 Strongyloidiasis (?) No Sasaki56 40/F – CSF and BC/Gram (+) HTLV-1 Strongyloidiasis (?) No Sasaki56 44/M – CSF and BC/Gram (−) HTLV-1T leukemia/lymphomaResected rectal cancer Strongyloidiasis (?) No Sasaki56 66/M – CSF and BC/Gram (+) HTLV-1 StrongyloidiasisDiverticulosis (?) No Sasaki56 46/M – CSF and BC/Gram (+) HTLV-1T leukemia/lymphoma Strongyloidiasis (?) Yes Sasaki56 49/M – CSFGram (+) HTLV-1 StrongyloidiasisAdenoma (?) No Present report (Case 3) 80/M 732 (98)358/65 CSF and BCGram (+)S. pasteurianus Leukemia Diverticulosis 28 No (endocarditis) Present report (Case 4) 86/M 580 (87)435/47 BC/Gram (−)S. gallolyticus Bladder cancer Diverticulosis 28 No (spondylodiscitis) F: female; M: male; BC: blood culture; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid. WBC (% N): White-cell count (per mm3) and % of neutrophils. Protein (mg/dl). Glucose (mg/dl). HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus; HTLV-1: Human T-Lymphotropic Virus type 1.

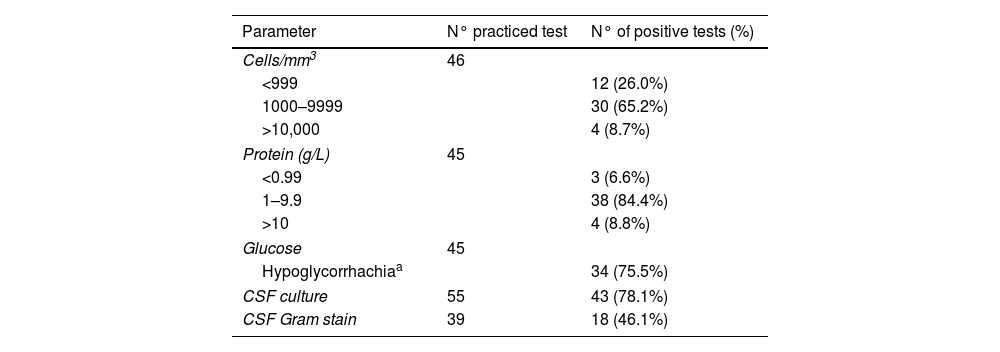

Table 3.Bacteriological, cytological and biochemical parameters of cerebrospinal fluid in the S. bovis meningitis.

Parameter N° practiced test N° of positive tests (%) Cells/mm3 46 <999 12 (26.0%) 1000–9999 30 (65.2%) >10,000 4 (8.7%) Protein (g/L) 45 <0.99 3 (6.6%) 1–9.9 38 (84.4%) >10 4 (8.8%) Glucose 45 Hypoglycorrhachiaa 34 (75.5%) CSF culture 55 43 (78.1%) CSF Gram stain 39 18 (46.1%)

Forty-five of the 64 patients (70.3%) had one or more underlying disease or predisposing factor (Tables 1 and 2). The most frequent conditions were immunosuppression (32.8%) and cancer (10.9%). The main cancer type was colorectal carcinoma (7 cases) and lymphoma/leukemia (7 cases). HIV/HTLV (10 cases) and steroids use (8 cases) was the most frequent immunosuppression causes. Four patients had local predisposing factors: CSF leak, surgery or spinal manipulation. Twelve patients (21.8%) with meningitis had Strongyloides disease.

MicrobiologyIn patients with intracranial focal infections, pus culture yielded diagnosis in 6 cases (66.7%), blood culture in 7 cases (77.8%) and CSF culture in one case (11.1%). In patients with meningitis CSF culture was positive in 13 cases (23.6%), blood culture was positive in 12 cases (21.8%) while 30 patients had both cultures positive (54.5%). CSF Gram stain revealed bacteria in 18 cases (46.1%).

In 23 cases, biotype or species identification was performed: 16 were caused by S. bovis biotype II (S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus: 7 cases, S. infantarius subsp. coli: 1 case and biotype II with no specified subspecies: 7 cases) and 8 by S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus. All tested strains were penicillin sensitive (MICs: 0.06–0.09mg/L). S. bovis was isolated in pure culture, except in 3 cases: one cerebral abscess (Fusobacterium necrophorum, Peptostreptococcus sp., and group G Streptococcus sp.) and two meningitis associated with infection by S. stercoralis (E. faecalis, and Klebsiella pneumoniae, respectively).

Treatment, outcomes and mortalityThe antibiotic therapy consisted of beta-lactam (penicillin or ceftriaxone in most cases) in 56 of 59 cases where treatment was specified. In 10 cases, the beta lactam was used in combination with other antibiotics (aminoglycosides in most cases). Duration of therapy ranged from 6 to 14 weeks in intracranial pyogenic infections; in patients with meningitis and no other infectious focus treatment duration ranged from 10 to 14 days, while in those with meningitis and either endocarditis or spondylodiscitis treatment lasted 4 weeks except in a case in which it lasted 6 weeks. Steroids were employed in 19 cases (in 17 cases of meningitis). Surgery was performed in 5 cases (2 abscesses, 2 subdural empyema and 1 case of meningitis with ventriculitis).

The overall mortality was 17.1% (11/64), being higher in intracranial infections than in meningitis: 55.5% (5/9) vs.16.4% (9/55); p=0.001. One patient had hearing loss as a sequel. No relapse was reported, with a follow-up duration of between 1–54 months (median 12 months).

Bowel pathologyUnderlying bowel disease was found in 39 patients (60.9%): 16 had neoplasms, 12 had intestinal Strongyloidiasis, 2 had actinic bowel disease, 2 had ulcerative colitis and 8 had diverticulosis.

Strongyloidiosis diagnostic was performed by visualizing eggs in stool in 8 cases and by intestinal biopsy in 4 cases. All four of them had abdominal symptoms, and all corresponded to meningitis. A thorough bowel study by pancolonoscopy or authopsy was performed in 40 patients found carcinoma or advanced adenoma in 11 (27.5%); only one patient had symptoms (2.5%).

DiscussionStreptococcus bovis often causes endocarditis, bacteremia, urinary tract infections and septic arthritis.57Streptococcus bovis rarely causes CNS infections in adults. In a large series of bacterial meningitis, S. bovis was found to cause only 0.3% of 1561 meningitis episodes.52 In our area, even when there is a high incidence of S. bovis infections,57 only 4 cases of CNS infection have been identified in 31 years. During the same period, however, we diagnosed 96 cases of CNS pneumococcal infections and 45 of CNS listeriosis.

Most CNS infections caused by S. bovis are meningitis, both in adults and children.3,43,52,58 Meningitis progresses as an acute clinical condition, not as fulminating as pneumococcal meningitis, although somehow more acute than in Listeria monocytogenes meningitis.59–62 Fever, headache and meningeal signs are present in most cases. CSF presents findings typical of purulent meningitis, similar to those of pneumococcal meningitis;59,60 75.5% of patients had low CSF glucose concentrations, similar to pneumococcal meningitis59 but higher than in Listeria infections.61,62 The diagnosis is usually easy, given the high diagnostic yield results from CSF and blood cultures. Gram stain of CSF is positive in less than half of the cases, an inferior yield to that observed in pneumococcal meningitis,59,60 but higher than in Listeria infections.61,62 The neurological and extraneurological complications are much less frequent than those caused by S. pneumoniae or L. monocytogenes. For these reasons, infection-related mortality, neurological sequelae, and relapse are also more infrequent.59–62

Compared with other CNS pathogens, such as meningococcus or pneumococcus, which rarely cause brain abscesses, 11% of the reported S. bovis CNS infections are brain abscesses, similar than in Listeria.63 Abscesses in S. bovis are more frequently supratentorial and multiple and entail a higher mortality than those caused by Listeria.5–10,63 Unlike meningitis, intracranial focal infections caused by S. bovis frequently have a subacute course and are more frequently associated with focal neurological deficits and a poor prognostic as well.5–10 Likewise, intracranial focal infections are frequently associated with other types of infection such as endocarditis, an association that is less frequent in meningitis.

Patients were mostly male and in their sixth and seventh life decades. Although S. bovis CNS infection can occur in healthy patients,33,37 they are usually associated with underlying conditions, mainly immunodepression like, HIV or HTLV-1 infection, immunosuppressive treatment or asplenia8,11,18,21,29,41,45,56 or cancer.45,52,55,56 The rate of cancer and immunosupression are similar to CNS infections caused by L. monocytogenes.61–63

Contact with animals and manure has been proposed as a risk factor for bowel colonization by S. gallolyticussubsp. gallolytiticus.64 Three of our four patients with CNS infection had contact with cattle. The rate of bacteremia has been previously linked with cattle population density in our geographical area.65

Streptococcus bovis is a commensal bacterium of the bowel, and systemic infections are probably secondary to intestinal translocation during an alteration in the intestinal mucosa.66 In an appreciable percentage of cases bowel lesions such as intestinal neoplasms, radiation colitis or Strongyloides colitis are detected.5,16,20,21,26,40,56

Twelve cases of S. bovis meningitis associated with S. stercoralis infestation have been included in this review.20,21,27,29,36,40,56 All but one had associated immunosuppression (steroids, HIV or HTLV-1 infections), and a number of cases had had other episodes of meningitis or bacteraemia caused by other intestinal flora.56 Gastrointestinal manifestations were observed in most cases in which symptoms were described, so hyperinfection should be assumed in most cases. Only one patient had cutaneous manifestation of strongyloidiosis,20 one patient had pseudomembranous colitis with a massive lower bleeding,40 and no cases of disseminated disease were reported. Stool examinations may be negative, so other studies especially duodenal aspiration or intestinal biopsy specimen yield the diagnosis in approximately 90% of cases.20,21,29,36,40

Colorectal neoplasms associated with S. bovis infection are usually asymptomatic in contrast to S. bovis related Strongyloides infestation.67 It is an accepted practice that all patients with bacteremia or endocarditis due to S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus undergo a thorough evaluation of the colon.2,67–69 However, the experience with CNS infections due to S. bovis is less well established. In this review, carcinomas or advanced adenomas were detected in 27.5% of the patients whose colon was properly studied. These figures are clearly higher than those of the general population of this age.2,67 It is uncertain if all neoplasms were associated with S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus (former S. bovis biotype I) since species identification was not universally performed. Only two cases (16.6%) of non-advanced adenomas in were found related to twelve cases of S. pasteurianus o S. bovis biotype II in our study, similar to the general population.2,70,71

Considering the impact of missing a neoplasm, in addition to those with infection by S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus diagnosis colonoscopy should be performed in patients with untyped S. bovis CNS infection. An additional advantage of this examination is the detection of other bowel diseases, such as Strongyloides colitis,20,21,29,36,40 ulcerative colitis, etc.

Streptococcus bovis is usually highly penicillin-sensitive, with few exceptions;72 beta-lactams are therefore the treatment of choice. Given the rarity of neurological complications, corticosteroids do not appear to play a role as they do in pneumococcal meningitis.59 Additionally, in endemic areas of Strongyloidiasis, these drugs can promote its dissemination and new episodes of meningitis.20

In pediatric patients, mainly neonates, S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus causes approximately 90% of all S. bovis menigitis.73 In adults the percentage is lower; in our review one third were caused by S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolytiticus and the rest were caused by S. bovis biotype II. Of the S. bovis biotype II identified, 87.5% were S. gallolyticus subsp. pauteurianus. It should be noted that our hospital reports a case of S. infantarius subsp. coli CNS infection. In our knowledge it is the first reported.in the literature.

Our study has limitations. Like all case report studies not all data are available for every patient. In addition, a rutinary test for Strongyloidiasis, neither colonoscopy or echocardiogram was performed in all patients. The biotype and species of S. bovis were also not determined in all cases.

In summary, CNS infections caused by S. bovis are rare in adults, and most are associated with S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus. Meningitis is the most common clinical form. The CSF findings are indistinguishable from those of pneumococcal meningitis, but the neurological complications are fewer and the prognosis is better. Unlike intracranial focal infections, meningitis caused by S. bovis is rarely associated with endocarditis. A high share of the cases is associated to underlying diseases, mainly immunosuppression and malignancy, similar than in Listeria CNS infections. In endemic areas, Strongyloidiasis should be ruled out for immunosuppressed patients with meningitis by S. bovis. The association with advanced colon neoplasms is stronger than expected. These patients’ bowel should therefore always be examined; however more studies are needed with proper species identification to establish whether the association is mainly with S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus, as occurs in bacteraemia and endocarditis.

Ethical approvalAll procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Data availabilityAnonymized clinical data sets are available upon corresponding author contact.

Financial supportNo funding from any public or private institution was received for the elaboration of this manuscript.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no competing interests.