Malaria remains a major health problem in Indonesia. It has been reported that the prevalence of parasitemia in Timika, Papua was 16.3%, and almost 50% of cases were caused by Plasmodium falciparum (P. falciparum).1 Papua province has not only the highest prevalence of malaria in Indonesia but also the highest prevalence of multidrug-resistance to both P. vivax and P. falciparum.2 Although artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) was adopted as the first-line anti-malarial treatment, studies have demonstrated the failure of ACT towards malaria elimination in several Southeast Asian countries.3 Hence, an alternative combination therapy against malaria is needed.

Ocimum sanctum (O. sanctum, Indonesian name Kemangi) belongs to the Lamiaceae family and is widely distributed throughout Indonesia. O. sanctum is used by Indonesian to treat several diseases, including malaria; however, the underlying mechanism remains elusive. A study revealed that the ethanolic leaf extract of O. sanctum displays more potent antiplasmodial activity than other Ocimum species in vitro.4 Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the synergistic anti-malarial properties of O. sanctum and artemisinin (ART) against the Plasmodium infection in vivo. In addition, the level of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) was examined.

The leaves of O. sanctum were collected from Malang, East Java, Indonesia. The species was identified and confirmed by a plant taxonomist of the herbarium unit, UPT Materia Medica, Batu, East Java, Indonesia. The ethanolic extract preparation was conducted as previously described.5 For in vivo experiments, female Balb/c mice between 8 and 12 weeks of age were used. Sixty-three mice were randomly assigned into seven groups (9 mice per group), namely negative control, positive control, infected mice treated with ART (0.036mg/g/day); two different doses of O. Sanctum extract (0.25 and 0.5mg/g/day); and combinations of artemisinin and O. Sanctum extract. The malaria model was performed by i.p. injection of Plasmodium berghei adjusted to 106 parasites in 0.2mL blood per mouse. Infected mice were then treated on the sixth day of infection with parasitemia approximately around 10% for seven consecutive days. To examine TGF-β levels, mice peritoneal macrophages on day seven post-treatment were cultured as described previously,6 and the supernatants were used to quantify the concentration of TGF-β (BioLegend) by ELISA.7–10 The study was approved by the medical ethics committee of Brawijaya University with Reference No. 27-KE. The reduction of parasitemia and TGF-β levels were analyzed by two and one-way ANOVA, respectively, followed by the Fisher LSD post hoc test using StatPlus. Significant differences were accepted when p<0.05.

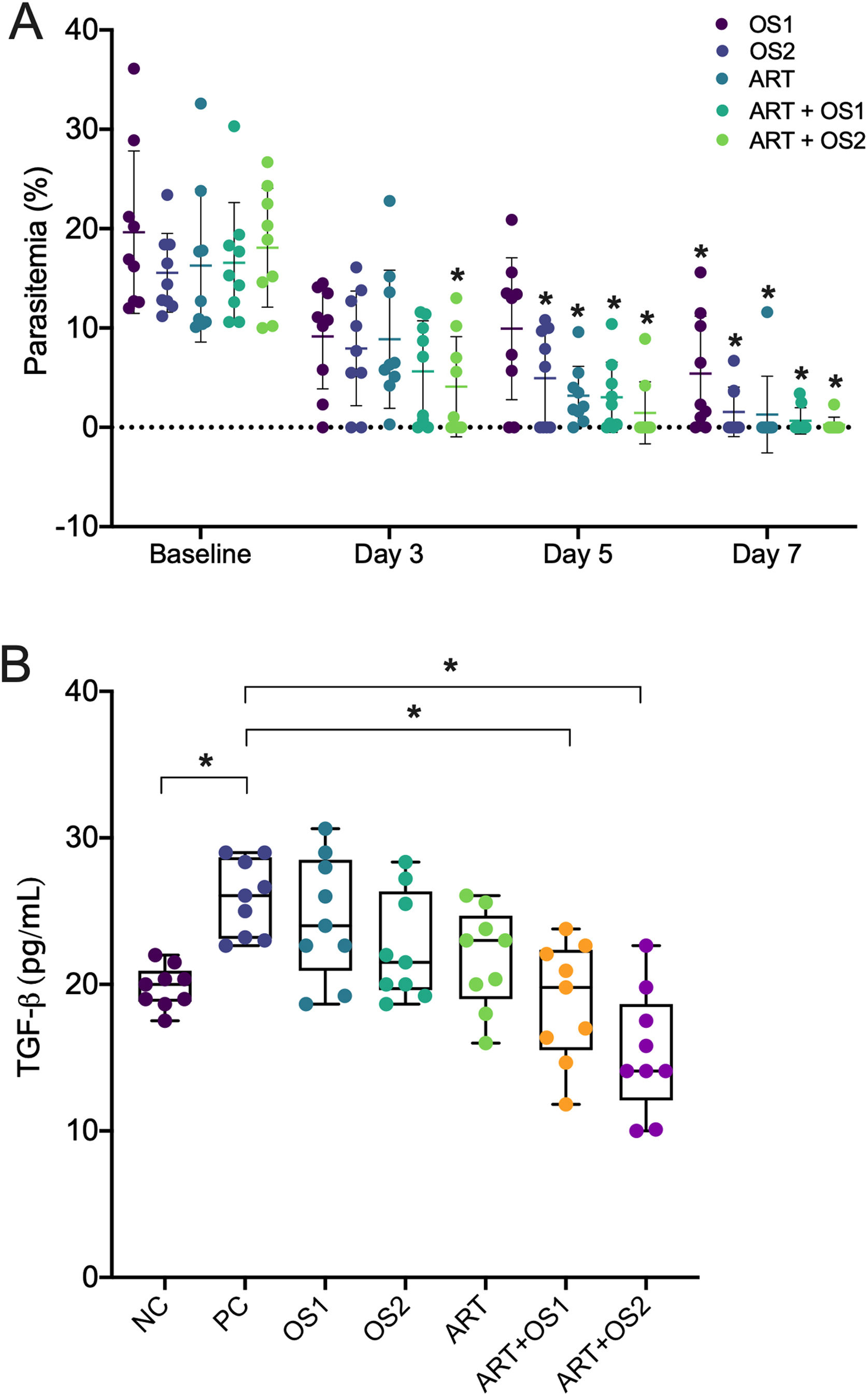

The reduction of parasitemia was observed in all groups started on day five of the treatment. Notably, the administration of ART and O. Sanctum extract at a dose of 0.5mg/g/day demonstrated a higher effectivity to speed up Plasmodium clearance than other groups (at day 3 compared to the baseline level, Fig. 1A). Moreover, the suppression of TGF-β was only observed in mice treated with combination therapy but not with monotherapy (Fig. 1B), thereby implying that combination therapy exhibits synergistic anti-malarial effects towards Plasmodium elimination. Various active constituents have been identified in the ethanolic extract of O. Sanctum, such as alkaloids, glycosides, flavonoids, phenols, saponins, tannins, steroids, and triterpenoids.4 The possible mechanisms of O. Sanctum extract in eliminating P. berghei may have occurred through the inhibition of hemozoin biocrystallization, protein synthesis, or β-haematin formation, stimulation of DNA fragmentation, and cytoplasmic acidification.4

Synergistic anti-malarial effects of Ocimum sanctum leaf extract and artemisinin. (A) Reduction of parasitemia. (B) TGF-β level by peritoneal macrophages during mice malaria infections measured by ELISA after 24h in vitro culture. Data are expressed as a mean±standard deviation (SD). (*) Indicates a significant difference compared to the baseline level or between two groups indicated in the graphs (p<0.05). OS1=O. Sanctum 0.25mg/g/day; OS2=O. Sanctum 0.5mg/g/day; ART=artemisinin 0.036mg/g/day; ART+OS1=artemisinin 0.036mg/g/day+O. Sanctum 0.25mg/g/day; ART+OS2=artemisinin 0.036mg/g/day+O. Sanctum 0.5mg/g/day; NC=negative control; PC, positive control.

In line with previous findings, this study showed that the upregulation of TGF-β levels was observed in P. berghei infected mice. Furthermore, the upregulation of TGF-β is known to be associated with the risk of complicated malaria.11 These results imply that TGF-β is linked to the disease severity of malaria. Therefore, a treatment that modulates the suppression of TGF-β would be beneficial to minimize malaria progression. In summary, the combination of ART and the ethanolic extract of O. Sanctum displays synergistic anti-plasmodial activity in vivo. Further studies are warranted to investigate the potential of O. Sanctum as an alternative ACT regimen in clinical settings.

Authors’ contributionZ.S.U. conceived, performed, analyzed, and wrote the article.

FundingN/A.

Conflict of interestNone to declare.