The role of pre- and post-test counselling in new HIV testing strategies to reduce delayed diagnosis has been debated. Data on time devoted to counselling are scarce. One approach to this problem is to explore patients’ views on the time devoted to counselling by venue of their last HIV test.

MethodsWe analysed data from 1568 people with a previous HIV test who attended a mobile HIV testing program in Madrid between May and December 2008.

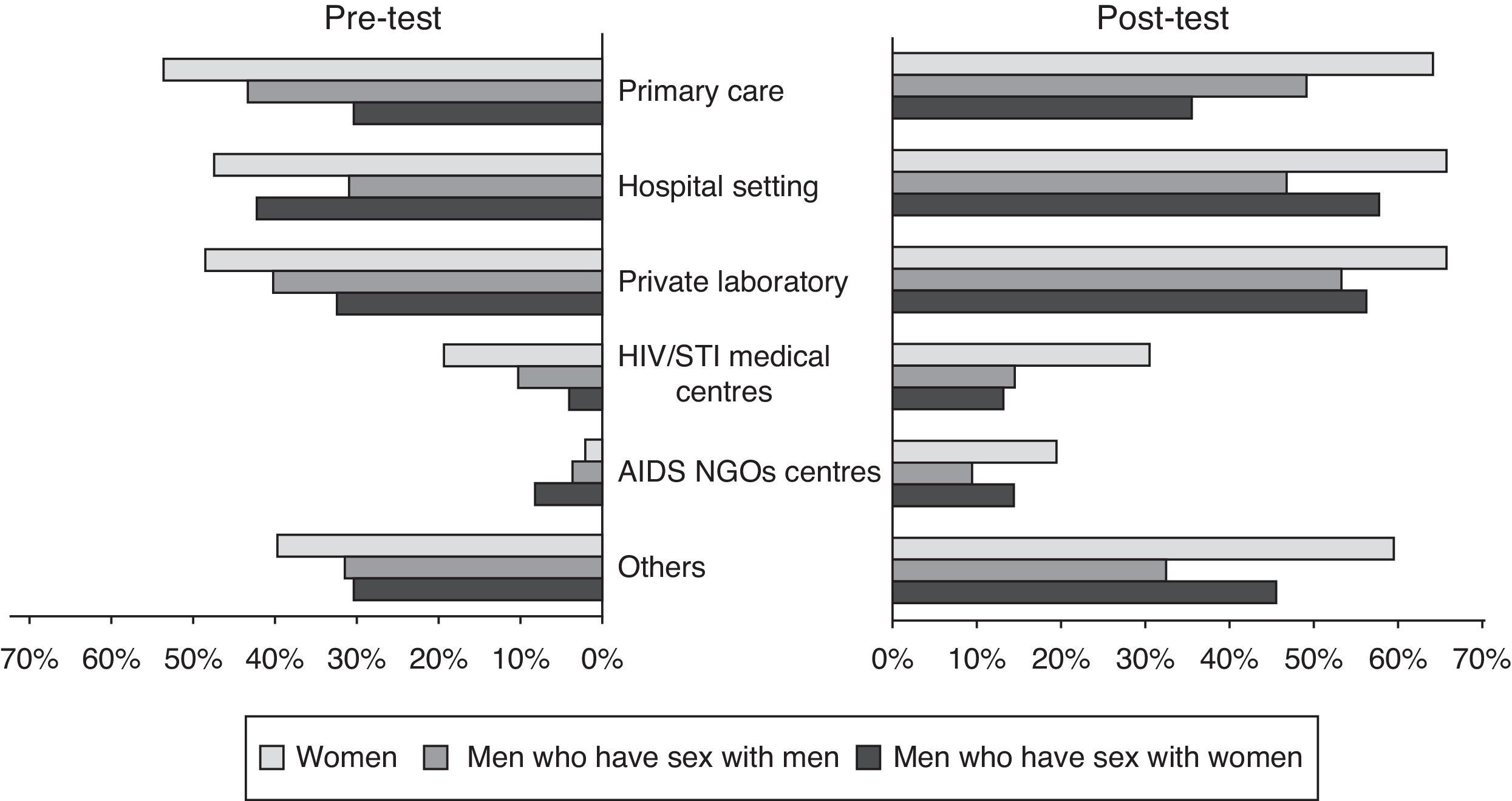

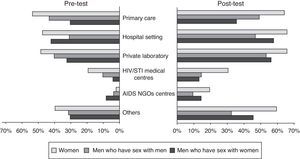

ResultsThe majority (71%) were men (48% had had sex with other men), 51% were <30 years, 40% were foreigners, 56% had a university degree, and 40% had the most recent HIV test within the last year. As regards pre-test counselling, 30% stated they were told only that they would receive the test; 26.3% reported <10min; 20.4% about 10min; and 24.2%, 15min or more. For post-test counselling: 40.2% stated they were told only that the test was negative; 24.9% reported 2–6min; 16.4% about 10min; and 18.5%, 15min or more. The percentage of participants who reported no counselling time was higher among those tested in general health services: primary care, hospital settings and private laboratories (over 40% in pre-test, over 50% in post-test counselling). Women received less counselling time than men in almost all settings.

ConclusionPolicies to expand HIV testing in general health services should take this current medical behaviour into account. Any mention of the need for counselling can be a barrier to expansion, because HIV is becoming less of a priority in developed countries. Oral consent should be the only requirement.

Las nuevas estrategias para reducir el diagnóstico tardío de VIH ponen en entredicho el papel del consejo pre-post test. Existe poca información sobre el tiempo dedicado al consejo. Un posible enfoque es explorar las opiniones de los pacientes sobre el tiempo dedicado al consejo según el lugar de la última prueba

MétodosSe analizan 1568 personas con prueba previa de VIH que acuden a un programa móvil en Madrid entre Mayo y Diciembre de 2008

Resultados71% eran hombres (48% hombres que tienen sexo con hombres), 51% < 30 años, 40% extranjeros, 56% universitarios y el 40% se hizo la última prueba en el ultimo año. Con respecto al consejo pre-test, el 30% refirió que únicamente se les comunicó que se les iba a realizar la prueba, el 26,3% reportó < 10 minutos, 20,4% alrededor de 10 y 24,2% 15 o más. Para el consejo post-test: el 40% refirió que únicamente se les comunicó el resultado negativo, 24,9% entre 2-6 minutos, 16,4% alrededor de 10 y 18,5% 15 o más. El porcentaje de participantes que dijo no recibir consejo fue mayor entre quienes se la habían hecho en servicios generales: atención primaria, hospitales y laboratorios privados (más del 40% en pre-test y más del 50% en post-test). En prácticamente todas las localizaciones, a las mujeres se les dedicó menos tiempo

ConclusiónLas políticas para expandir la prueba de VIH en servicios generales deben considerar el comportamiento médico actual. Cualquier mención a la necesidad de consejo puede resultar una barrera a la expansión puesto que el VIH ya no es prioridad en los países desarrollados. El consentimiento verbal debiera ser el único requisito

A recent report from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control states: “Surveillance data from a number of European countries reveal high and increasing numbers of undiagnosed infections and a high proportion of late presenters among those diagnosed. These findings indicate that current efforts to diagnose HIV early are failing and there is an urgent need to review current HIV testing strategies across Europe”.1 Those who are diagnosed late have greater risk of HIV-related morbidity and mortality, leading to higher costs to the health system; they also have more risk behaviours and higher viral load, leading to more HIV transmission.2–4 A recent systematic review on barriers to HIV testing in Europe concludes that the body of literature addressing this subject is relatively sparse and further exploration is needed. Moreover, almost all the studies focus on men who have sex with men (MSM) and immigrants, and most were conducted in the UK or the Netherlands.5

Since 2006, the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended that diagnostic HIV testing and opt-out HIV screening be a part of routine clinical care,6 resulting in substantial cost reduction and increased feasibility of HIV testing in some settings.7 There is little compelling evidence that counselling results in behaviour change for seronegative individuals.8–10 Furthermore, doctors perceive lack of time and training for counselling as an important barrier to performing more HIV tests.11–13 That being said, most current international and national guidelines continue to emphasize the importance of pre- and post-test counselling as an essential part of the HIV testing process.1 In some cases, the term “brief pre-test information” (about 7–10min) is used instead of “counselling”, but the amount of information recommended to be provided is still considerable.14 In practice, HIV exceptionalism is maintained as compared to the diagnosis of other diseases of similar potential severity.

In this debate, the time currently devoted in practice to pre- and post-test counselling remains unknown. This study aims to estimate the time actually devoted to counselling in different venues (with special focus on those services targeting the general population), by asking patients who attended a rapid HIV testing program about the time devoted to counselling during their last HIV test. Services targeting the general or non-specific population account for most HIV tests in Spain and many other countries.15,16

MethodsBetween May and December 2008, a mobile unit (a van) offered free, rapid HIV testing in some busy streets of Madrid. Those interested in taking the test, were given information about rapid testing, gave their signed, informed consent and received a brief pre-counselling session. A blood-based test (Determine HIV-1/2) was performed by finger prick inside the van by a trained nurse/doctor. While waiting for the test results, participants completed an anonymous and brief self-administered paper questionnaire that recorded sociodemographic information, sexual and injecting risks behaviours, and different aspects related with HIV testing experience. This questionnaire was collected in a sealed envelope at the delivering of the test results.

Those with a previous positive test were not included in the analysis. From the 3120 people who underwent testing, in this sub-study we analysed the 1568 participants who had at least one previous test (excluding 1466 individuals who had never been tested in the past, and 86 who had been previously tested but had missing values in the question referred to the venue in which the last testing episode took place or in the ones referring to time they thought had been devoted to pre- and post-test counselling).

The venue of the last testing episode was explored through a multiple-choice question with 12 closed possible answers and one open-ended. It included services targeting the general or non-specific population (primary care, hospital settings, private laboratories, etc.), and services targeting high-risk population (HIV/STI centres, AIDS NGOs, etc.). Pre-test counselling, was defined as the explanation of the importance of testing, mechanism of transmission of HIV, the implications of the test, etc. Post-test counselling, since all of them were negative on that previous test, was defined as the information on risk behaviours, harm reduction and prevention, window period, etc. Time devoted to counselling was explored through a multiple-choice question with 4 time intervals (“15min or more”, “about 10min”, “about 5min”, “2 or 3min” – the last two were combined as “less than 10min” in the analysis) and “None, I was only told it was going to be performed” for the pre-test, and “None, I was told it was negative and little more” for the post-test.

The characteristics of the participants are analysed stratifying intro three categories of gender/sexual behaviour: women, men who have sex exclusively with women (MSW), and men who have sex with other men (MSM).

Then, we calculated the percentage of respondents in each time category of pre- and post-test counselling, stratified by venue of the last HIV test. At first, the analysis was performed separately according to the time elapsed since the last test (less than 12 months vs. more than 12 months) but, since the results were similar the analysis was performed on whole. The proportion of participants who reported that no time was devoted to counselling was calculated by gender/sexual behaviour and venue of the test. Statistical significance was analysed using the χ2-test.

The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III.

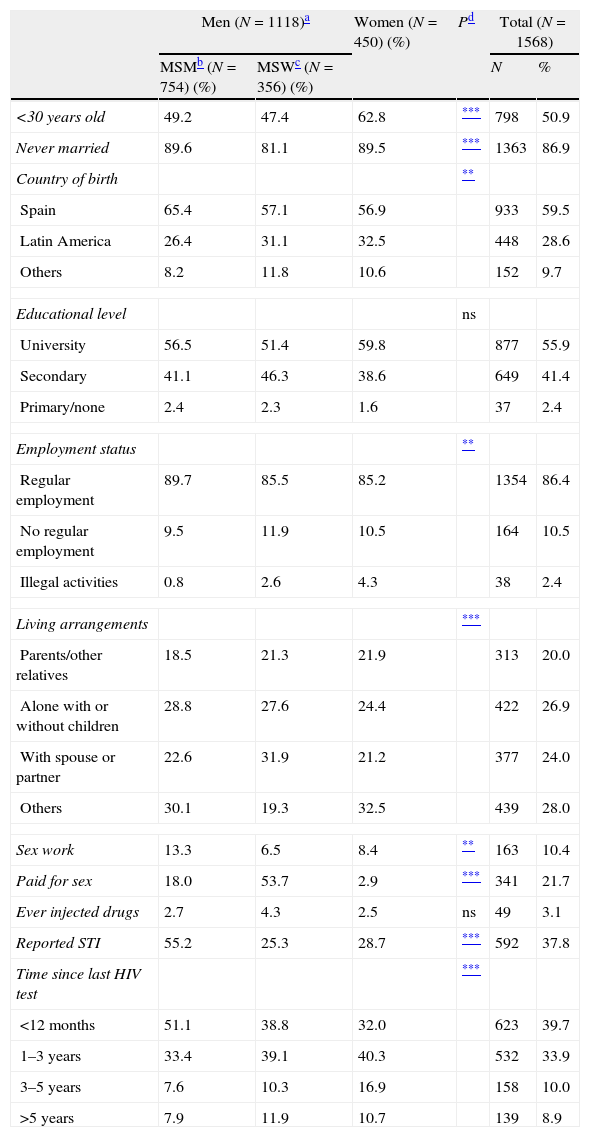

ResultsOf the 1568 participants analysed, 48% of respondents were MSM, 23% were heterosexual men (MSW), and 29% were women. Half (51%) were younger than 30, and women were generally younger than men (p<0.05). Forty percent were born outside of Spain, mostly in Latin America (75%), and 56% had university education. Among MSW, 6.5% had ever engaged in sex work versus 13% of MSM and 8% of women (p<0.05), however, the proportion who had paid for sex was twice as high in MSW (54%) as in MSM (18%), versus only 3% of women (p<0.05). Over half (55%) of MSM had been diagnosed with an STI vs. 25% of MSW and 29% of women (p<0.05). Only 3% had ever injected drugs (Table 1).

Sociodemographic and behavioural risk factors in people with a previous HIV test who received rapid HIV testing in a mobile program, Madrid, 2008.

| Men (N=1118)a | Women (N=450) (%) | Pd | Total (N=1568) | |||

| MSMb (N=754) (%) | MSWc (N=356) (%) | N | % | |||

| <30 years old | 49.2 | 47.4 | 62.8 | *** | 798 | 50.9 |

| Never married | 89.6 | 81.1 | 89.5 | *** | 1363 | 86.9 |

| Country of birth | ** | |||||

| Spain | 65.4 | 57.1 | 56.9 | 933 | 59.5 | |

| Latin America | 26.4 | 31.1 | 32.5 | 448 | 28.6 | |

| Others | 8.2 | 11.8 | 10.6 | 152 | 9.7 | |

| Educational level | ns | |||||

| University | 56.5 | 51.4 | 59.8 | 877 | 55.9 | |

| Secondary | 41.1 | 46.3 | 38.6 | 649 | 41.4 | |

| Primary/none | 2.4 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 37 | 2.4 | |

| Employment status | ** | |||||

| Regular employment | 89.7 | 85.5 | 85.2 | 1354 | 86.4 | |

| No regular employment | 9.5 | 11.9 | 10.5 | 164 | 10.5 | |

| Illegal activities | 0.8 | 2.6 | 4.3 | 38 | 2.4 | |

| Living arrangements | *** | |||||

| Parents/other relatives | 18.5 | 21.3 | 21.9 | 313 | 20.0 | |

| Alone with or without children | 28.8 | 27.6 | 24.4 | 422 | 26.9 | |

| With spouse or partner | 22.6 | 31.9 | 21.2 | 377 | 24.0 | |

| Others | 30.1 | 19.3 | 32.5 | 439 | 28.0 | |

| Sex work | 13.3 | 6.5 | 8.4 | ** | 163 | 10.4 |

| Paid for sex | 18.0 | 53.7 | 2.9 | *** | 341 | 21.7 |

| Ever injected drugs | 2.7 | 4.3 | 2.5 | ns | 49 | 3.1 |

| Reported STI | 55.2 | 25.3 | 28.7 | *** | 592 | 37.8 |

| Time since last HIV test | *** | |||||

| <12 months | 51.1 | 38.8 | 32.0 | 623 | 39.7 | |

| 1–3 years | 33.4 | 39.1 | 40.3 | 532 | 33.9 | |

| 3–5 years | 7.6 | 10.3 | 16.9 | 158 | 10.0 | |

| >5 years | 7.9 | 11.9 | 10.7 | 139 | 8.9 | |

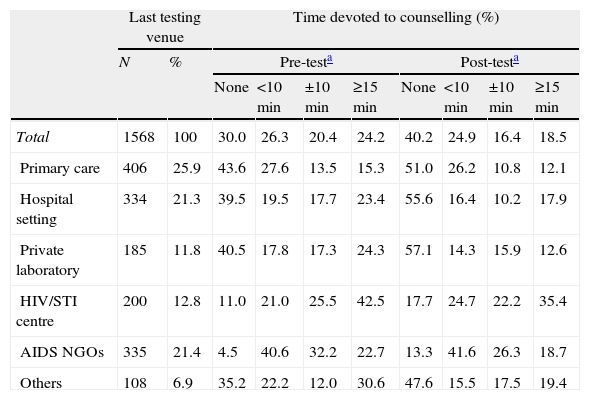

Forty percent had received their last HIV test within the last year (51% of MSM, 39% of MSW and 32% of women, p<0.05) (Table 1). In nearly 60% of cases, the test was performed in general health services (primary care, hospital settings) or services targeting a non-specific population (private laboratories) (Table 2).

Venue of last HIV test and time devoted to counselling, Spain.

| Last testing venue | Time devoted to counselling (%) | |||||||||

| N | % | Pre-testa | Post-testa | |||||||

| None | <10min | ±10min | ≥15min | None | <10min | ±10min | ≥15min | |||

| Total | 1568 | 100 | 30.0 | 26.3 | 20.4 | 24.2 | 40.2 | 24.9 | 16.4 | 18.5 |

| Primary care | 406 | 25.9 | 43.6 | 27.6 | 13.5 | 15.3 | 51.0 | 26.2 | 10.8 | 12.1 |

| Hospital setting | 334 | 21.3 | 39.5 | 19.5 | 17.7 | 23.4 | 55.6 | 16.4 | 10.2 | 17.9 |

| Private laboratory | 185 | 11.8 | 40.5 | 17.8 | 17.3 | 24.3 | 57.1 | 14.3 | 15.9 | 12.6 |

| HIV/STI centre | 200 | 12.8 | 11.0 | 21.0 | 25.5 | 42.5 | 17.7 | 24.7 | 22.2 | 35.4 |

| AIDS NGOs | 335 | 21.4 | 4.5 | 40.6 | 32.2 | 22.7 | 13.3 | 41.6 | 26.3 | 18.7 |

| Others | 108 | 6.9 | 35.2 | 22.2 | 12.0 | 30.6 | 47.6 | 15.5 | 17.5 | 19.4 |

With respect to time devoted to pre-test counselling, 30% of respondents stated they were told only that the test was going to be performed, and 26.3% stated they received less than 10min of counselling. For post-test counselling, the proportion of respondents who were told little more than that the test was negative was 40.2%, while 24.9% stated they had received less than 10min of counselling. Of those who were tested in health services targeting the general population, 40% indicated they received no pre-test counselling and 50% received no post-test counselling. These proportions were substantially lower, however, in specific services for HIV diagnosis. This was a constant regardless of the time elapsed since the last test The analysis by gender/sexual behaviour found that 37.5% of women versus 26.7% of MSW and 25.4% of MSM received no pre-test counselling (p<0.001); and 53.1% of women versus 38.5% of MSW and 33.6% of MSM had no post-test counselling (p<0.001). The proportion of women who reported no counselling time was higher in all settings, except for pre-test counselling in AIDS NGOs (Fig. 1).

DiscussionThis study shows that no pre-test or post-test counselling whatsoever was received in half of the HIV tests performed in non-specialised services, according to the patient's perspective. An additional 25% of respondents received only brief information of less than 6min.

To our knowledge, there are no studies evaluating the duration of pre- and post-test counselling from the clients’ perspective and covering people who have been tested in different HIV testing venues. Therefore, it's very difficult to compare our outcomes. In a 2005 study in British Columbia17 primary care physicians indicated that counselling was not being carried out in about 30% of cases. And the time spent on counselling was a median of 6min for pre-test and 4min for post-test on negatives. Our findings are consistent with those found in that study, and the fact that the time elapsed since the last test had no impact on them, make them trustworthy. Moreover, several studies, have examined physicians’ perceived barriers to HIV testing;11–13,18 these have found that two of the most common reasons given for not expanding HIV testing in general health services (primary care, hospital emergencies, etc.) are: first, lack of time, and second, perceiving themselves as not having the appropriate skills to address sexual behaviour and feeling discomfort in discussing HIV. It is true that physicians might mention similar reasons when asked about expanding screening for other health problems;19 however there are good reasons for time constraints and discomfort to be real barriers due to HIV exceptionalism, with the commitment to provide pre- and post-test counselling and the need for prior training and time to provide these services.20 Our results are consistent with this all, showing that counselling is not taking place in a not negligible proportion, especially in health services targeting the general population where it reaches 40% for pre-test and 50% for post-test. As expected, the proportion of no-counselling was lower in services for HIV diagnosis, since they are specifically designed for it, the staff are trained to do so and is usually an essential part of their program. Notwithstanding, there is clear evidence that the general health services, especially primary care, account for most of the HIV tests in many countries including Spain (15;16), and these are the services that are most likely to provide early diagnosis of infection in asymptomatic people who do not perceive themselves to be at risk for HIV, such as older heterosexual men.

We also must bear in mind that, as a result of the changing epidemiological situation,21 the loss of novelty and the availability of treatments, HIV has become less of a priority for European societies and health personnel. Therefore, resources for prevention and control are also decreasing.22–26 This is particularly evident in countries such as Spain, where the AIDS epidemic reached extremely high levels in recent decades.27 Under these conditions, and if current international guidelines1,14 must be followed, it is unlikely that these countries can achieve universal or broad range HIV testing in general health services leading to a significant reduction in the percentage of late diagnosis and of the population known to be infected. Accordingly, the central message of the guidelines should not be geared to the special requirements of the HIV test. On the contrary, only guidelines emphasizing that primary care doctors need neither more time nor more preparation to recommend HIV testing than what is required for screening tests for other vital health problems (i.e. cancer) have the potential to reverse this situation. In fact, all the requirements that are repeatedly mentioned and emphasized in the guidelines (information, confidentiality, referral to treatment, etc.) are the same as for other health problems. Doctors from general health services should focus their scarce time on what they can do well and efficiently: recommending the test to all their patients when it is indicated and conveying the result. They should also be clear that they will very rarely have to communicate a positive result as the prevalence in their population will be very low. Therefore, the time invested in post-test counselling to convey the result, give advice on changing risk behaviours, and ensure follow-up care will be necessary only in the few individuals who are HIV positive, similar to what is done when they diagnose cancer or other potentially serious diseases.

Also worth mentioning is that we have no information to discriminate whether the fact that a significantly higher percentage of women than men reported no counselling time is a reality or simply a differential perception by gender. This finding was not related to pregnancy tests because these represented a very small percentage of HIV tests in women.

The generalization of the results of this study is subject to several limitations. First, it only describes the patient's perception of counselling time with reference to the last HIV test. Second, the last test was performed in different types of services, although participants were recruited from a single service. Therefore we do not know whether the results would differ if we had included participants recruited in other services: it is possible that the “no time” may be underestimated for NGOs or overestimated for general health services. The high proportion of graduates in the sample must be also taken into account. Despite this, and given the consistency with other studies, we would not expect to find very different outcomes in other populations.

Pre- and post-HIV test counselling is not taking place in a high proportion of the test performed, especially in health services targeting the general population. Counselling was not always fulfilled even when HIV was a priority, it would not be unwise to assume that nowadays it would be harder to achieve. Policies to expand HIV testing in general health services should take this current medical behaviour into account.

FundingThe study was funded by FIS: PI09/1706 and FIPSE: 36634/07.

Conflict of interestAuthors have no conflict of interest to declare

Madrid Rapid HIV Testing Group: Jorge Álvarez Rodriguez, Jorge Gutiérrez Perera, Mónica Ruiz García, M. Elena Rosales-Statkus, Rebeca Sánchez Pérez.