The overall increase in the use of carbapenems could lead to the selection of carbapenem-resistant bacteria. The objectives of this study were to analyze carbapenem use from 2008 to 2015 and their prescription profile in 58 hospitals affiliated to the VINCat Programme (nosocomial infection vigilance system).

MethodsRetrospective, longitudinal and descriptive study of carbapenem use. Consecutive case-series study, looking for carbapenem prescription characteristics, conducted in January 2016. Use was calculated in defined daily doses (DDD)/100 patient-days (PD); prescription profiles were assessed using a standardized survey.

ResultsCarbapenem use increased 88.43%, from 3.37 DDD/100-PD to 6.35 DDD/100-PD (p<0.001). A total of 631 patients were included in the prescription analysis. Carbapenems were prescribed empirically in 76.2% of patients, mainly for urinary tract and intra-abdominal infections due to suspicion of polymicrobial mixed infection (27.4%) and severity (25.4%).

ConclusionA worrying increase in carbapenem use was found in Catalonia. Stewardship interventions are required to prevent carbapenem overuse.

El aumento global del consumo de carbapenemas podría seleccionar bacterias resistentes a los carbapenemas. Los objetivos del estudio fueron analizar el consumo de carbapenemas entre 2008-2015 y su perfil de prescripción en 58 hospitales afiliados al Programa VINCat.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo, longitudinal y descriptivo de consumo de carbapenemas. Estudio de series de casos consecutivos buscando características de la prescripción realizado en enero de 2016. Consumo calculado en dosis diarias definidas (DDD)/100 pacientes/días (PD); perfil de prescripción evaluado mediante una encuesta estandarizada.

ResultadosEl consumo de carbapenemas aumentó un 88,43%, de 3,37 DDD/100 PD a 6,35 DDD/100 PD (p<0,001). Se incluyeron 631 pacientes en el análisis de prescripción. Un 76,2% recibió carbapenemas empíricamente para infecciones del tracto urinario e intra-abdominales por sospecha de infección mixta polimicrobiana (27,4%) y gravedad (25,4%).

ConclusiónSe produjo un preocupante aumento del consumo de carbapenemas en Cataluña, por lo que son necesarias intervenciones específicas para evitar su uso excesivo.

In recent years, an increase in the use of carbapenems has been noticed.1 This trend is troublesome since carbapenem overuse may stimulate different resistance pathways, including outer membrane protein mutations and selection of β-lactamases capable of hydrolyzing carbapenems.2–4 Major consequences of this phenomenon are the increasing carbapenem resistance amongst Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacteriaceae.2,5,6 The rise in the incidence of infections due to extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL)-producing bacteria may partly explain this overuse.7 These bacteria may cause serious infections and can hydrolyze most broad spectrum β-lactam antibiotics, excepting carbapenems.8 The objective of this study was to analyze the trends in carbapenem use (from 2008 to 2015) and their current prescription profile, among acute care hospitals in Catalonia, an autonomous community of Spain with a population of 7.5 million.

MethodsSetting and study designAll acute care hospitals affiliated to the VINCat Program, which is the Health Care Associated Infection (HAI) Surveillance System in Catalonia,7 were invited to participate and were subsequently classified into three groups according to VINCat criteria7 depending on their size and complexity.

To analyze trends of carbapenem consumption we performed a retrospective, longitudinal and descriptive study of data collected from 2008 to 2015. To assess the carbapenem prescription profile a consecutive case-series study was conducted in January 2016 looking for reasons for carbapenem prescription. In both studies, results were compared between different hospital groups.

Data collectionCarbapenem consumption (Code J01DH in the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification) was recorded by each hospital and electronically transmitted to the VINCat Coordinating Centre (CC) once a year.9 The VINCat-CC established the criteria for the compilation of data in a standardized way available in VINCat Program website.7 Consumption data and patient-days (PD) of acute care hospitals were included excepting those from pediatrics, hospital wards with minimal consumption and units that do not produce PD such as emergency services. Consumption was calculated in defined daily doses (DDD)/100 PD.

To assess the prescription profile of these antimicrobials, a standardized survey was sent to all hospitals, asking for demographic data, type (community-acquired, nosocomial or HAI7) and focus of infection, length and type (empirical or directed) of treatment and reasons for its discontinuation (completion of treatment, de-escalation, failure, adverse reactions or death) and microbiological data. Multiple answers were allowed. The survey was completed by trained pharmacists who extracted the information from the clinical sheet and asked the prescribers for the reasons for the initial choice of carbapenem among the following options: suspicion of polymicrobial mixed infection, suspicion of ESBL-producing bacteria, suspicion of P. aeruginosa, adherence to ongoing local protocols, rescue therapy and patient initial severity.

Measurement of drug consumptionDDD/100 PD was used to calculate the average consumption rate according to ATC/DDD system methodology. Days of admission and discharge were counted as one day. A weighted mean of the carbapenem use from each of the participating hospitals was used to calculate the consumption of these antibiotics for each hospital group, expressed in DDD and divided by the sum of their PD. The 2016 update of DDD was applied to calculate the consumptions expressed in DDD/100 PD during the study period.

Statistical analysisA global pooled mean was calculated for each year and/or group of hospitals aggregating data on carbapenem use from hospitals in each group. Trends were determined with Spearman's rho correlation coefficient. p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 18.0 (IBM Corp.). Continuous variables were expressed as mean (±SD).

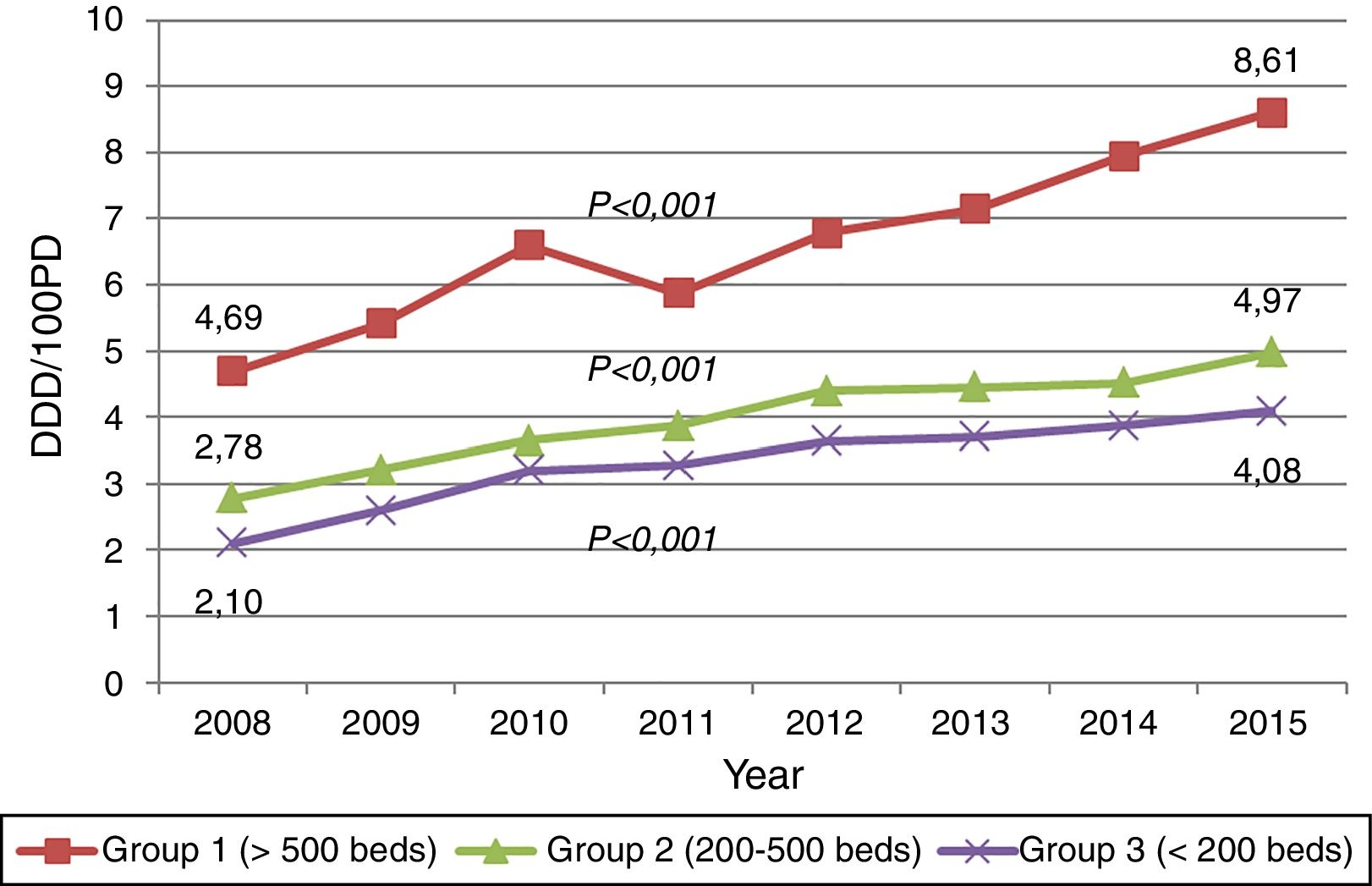

ResultsTrends of carbapenem useCarbapenem consumption among 58 hospitals increased 88.43% (p<0.001) from 3.37 DDD/100 PD in 2008 to 6.35 DDD/100 PD in 2015, largely because of meropenem (245.38%) and ertapenem (148.72%). The DDD/100 PD of carbapenem accounted for 4.51% and 7.73% of the total antibacterial consumption in 2008 and 2015, respectively.

The consumption of imipenem-cilastatin decreased 29.05% during this study period. The upward trends of carbapenem consumption were observed in all three hospital groups (Fig. 1). Data concerning the trends in consumption by hospital groups and the inclusions by type of hospital-year are available in the website.7

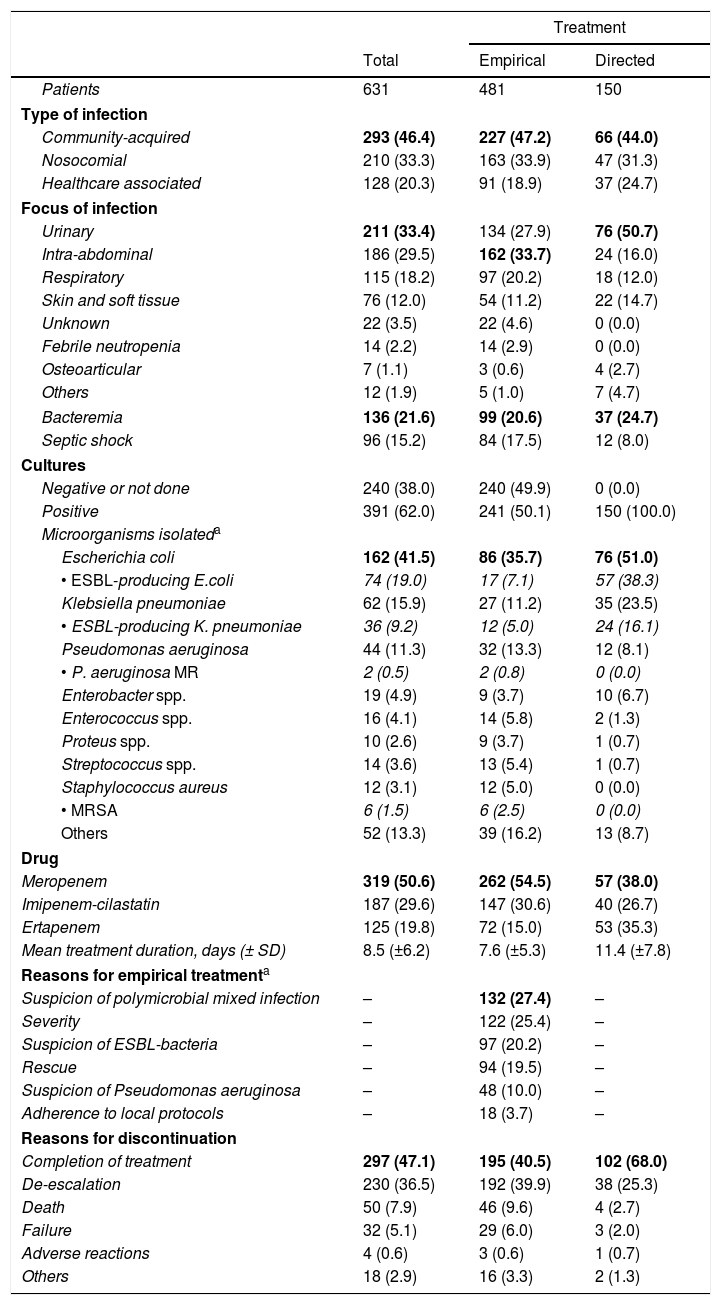

Carbapenem prescription profileA total of 47 hospitals participated in the study. Of these, 9 (19.2%) belonged to group I, 17 (36.2%) to group II and 21 (44.7%) to group III. Each center had to record data from those patients initiating carbapenem therapy for any reason, in a consecutive way. A total of 631 patients were included in the study, 401 (63.5%) men, with a mean age of 77 (±16.8) years. Detailed etiology of infections and characteristics of carbapenem therapy are described in Table 1 and 2E (as supplementary data).

Characteristics and etiology of infections among 631 patients receiving empirical or directed carbapenem therapy.

| Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Empirical | Directed | |

| Patients | 631 | 481 | 150 |

| Type of infection | |||

| Community-acquired | 293 (46.4) | 227 (47.2) | 66 (44.0) |

| Nosocomial | 210 (33.3) | 163 (33.9) | 47 (31.3) |

| Healthcare associated | 128 (20.3) | 91 (18.9) | 37 (24.7) |

| Focus of infection | |||

| Urinary | 211 (33.4) | 134 (27.9) | 76 (50.7) |

| Intra-abdominal | 186 (29.5) | 162 (33.7) | 24 (16.0) |

| Respiratory | 115 (18.2) | 97 (20.2) | 18 (12.0) |

| Skin and soft tissue | 76 (12.0) | 54 (11.2) | 22 (14.7) |

| Unknown | 22 (3.5) | 22 (4.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 14 (2.2) | 14 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Osteoarticular | 7 (1.1) | 3 (0.6) | 4 (2.7) |

| Others | 12 (1.9) | 5 (1.0) | 7 (4.7) |

| Bacteremia | 136 (21.6) | 99 (20.6) | 37 (24.7) |

| Septic shock | 96 (15.2) | 84 (17.5) | 12 (8.0) |

| Cultures | |||

| Negative or not done | 240 (38.0) | 240 (49.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Positive | 391 (62.0) | 241 (50.1) | 150 (100.0) |

| Microorganisms isolateda | |||

| Escherichia coli | 162 (41.5) | 86 (35.7) | 76 (51.0) |

| • ESBL-producing E.coli | 74 (19.0) | 17 (7.1) | 57 (38.3) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 62 (15.9) | 27 (11.2) | 35 (23.5) |

| • ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae | 36 (9.2) | 12 (5.0) | 24 (16.1) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 44 (11.3) | 32 (13.3) | 12 (8.1) |

| • P. aeruginosa MR | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Enterobacter spp. | 19 (4.9) | 9 (3.7) | 10 (6.7) |

| Enterococcus spp. | 16 (4.1) | 14 (5.8) | 2 (1.3) |

| Proteus spp. | 10 (2.6) | 9 (3.7) | 1 (0.7) |

| Streptococcus spp. | 14 (3.6) | 13 (5.4) | 1 (0.7) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 12 (3.1) | 12 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| • MRSA | 6 (1.5) | 6 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Others | 52 (13.3) | 39 (16.2) | 13 (8.7) |

| Drug | |||

| Meropenem | 319 (50.6) | 262 (54.5) | 57 (38.0) |

| Imipenem-cilastatin | 187 (29.6) | 147 (30.6) | 40 (26.7) |

| Ertapenem | 125 (19.8) | 72 (15.0) | 53 (35.3) |

| Mean treatment duration, days (± SD) | 8.5 (±6.2) | 7.6 (±5.3) | 11.4 (±7.8) |

| Reasons for empirical treatmenta | |||

| Suspicion of polymicrobial mixed infection | – | 132 (27.4) | – |

| Severity | – | 122 (25.4) | – |

| Suspicion of ESBL-bacteria | – | 97 (20.2) | – |

| Rescue | – | 94 (19.5) | – |

| Suspicion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa | – | 48 (10.0) | – |

| Adherence to local protocols | – | 18 (3.7) | – |

| Reasons for discontinuation | |||

| Completion of treatment | 297 (47.1) | 195 (40.5) | 102 (68.0) |

| De-escalation | 230 (36.5) | 192 (39.9) | 38 (25.3) |

| Death | 50 (7.9) | 46 (9.6) | 4 (2.7) |

| Failure | 32 (5.1) | 29 (6.0) | 3 (2.0) |

| Adverse reactions | 4 (0.6) | 3 (0.6) | 1 (0.7) |

| Others | 18 (2.9) | 16 (3.3) | 2 (1.3) |

MR: multiresistant.Data are given in n (%).

Text in bold in order to show that these data are the more prevalent; text in italics reflects data of multidrug resistant microorganisms (ESBL, Pseudomonas MR and MRSA).

The study shows a sustained and widespread increase in carbapenem use in Catalonia (Spain) during this eight-year period. This trend is consistent with tendencies observed in other European countries,1,8 with the peculiarity that we documented significant increases in all three hospital groups. In addition, our consumption level is amongst the highest reported to date, reaching a figure of 6.35 DDD/100 PD in 2015 (8.61 DDD in large university hospitals and 4.08 DDD in small hospitals). Meropenem has been largely the most prescribed carbapenem, while consumption of imipenem-cilastatin has shown a downward trend. This finding is different from other countries, as France, where imipenem-cilastatin remains the most prescribed carbapenem.10 These features emphasize the need of performing stewardship activities according to regional data, including small hospitals.8

Regarding the characteristics of infections of patients initiating carbapenem therapy, it has to be underlined the coincidence in most features of our series (etiology, type and origin of infection, severity and outcomes) with other unselected series of patients.10 The most striking finding was the high proportion of patients (76.2%) receiving carbapenems on empirical basis superior to the 52.6% found in a French study.10 Most patients in this group had intra-abdominal or urinary tract infections, which coincides respectively with the suspicion of a polymicrobial mixed infection or multidrug-resistant bacteria as the main reasons for choosing a carbapenem.

In an effort to use carbapenems judiciously, clinicians should balance the risk of ineffective therapy against unnecessary broad antibiotic treatment. According to current available knowledge, a high number of patients in this series could have been treated with non-carbapenem β-lactam antibiotics. A recent review of non-carbapenem β-lactams for treatment of ESBL-infections concluded that β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations may be a reasonable choice to treat low-moderate severity infections, from urinary or biliary sources and with piperacillin minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC)<4μg/ml.11 However, until more data is available, for severe cases, high inoculum infections and elevated piperacillin MICs, carbapenems would remain the drug of choice.11 In addition to β-lactamase inhibitors, cephamycins and cefepime may also be used, although with a lower level of evidence.11,12

Furthermore, a major strategy to decrease the use of carbapenems, especially in empiric decisions, may consist in promoting the use of good clinical decision trees to predict resistance.2 Other valuable strategies may include stimulating de-escalation and shortening the length of therapy. Our proportion of de-escalation agrees with other studies available in the literature, which ranged from 10.0% to 60.0%.13 These figures should improve in the next future by considering de-escalation an essential part of antimicrobial stewardship programs.14 Our data also shows a relatively longer duration of treatment (7.6 days in empirical and 11.4 days in directed treatment groups) in comparison with other studies, ranging from 6 to 9 days.10,14 Shortening days of therapy (without losing efficacy) appears as the most effective way to reduce drug consumption and antibiotic pressure, both at individual and global levels. Although the optimal duration of antibiotic therapy for different infections is still unclear, recent studies show that it could be shortened in most of them.15

Our study has certain limitations; although our data reflects accurately the trends of carbapenem consumption in our community, they cannot be extrapolated to other areas or countries. In addition, our survey is useful to illustrate the clinical practice of prescribers, but it is not a controlled study.

In conclusion, over the recent years a sustained and widespread increase in the carbapenem use has been noticed in acute care hospitals of different size and complexity in Catalonia. Stewardship interventions giving support to the use of alternative non-carbapenem antibiotics in these settings and promoting de-escalation and shortened therapy are required to avoid carbapenem overuse.

FundingThe VINCat Program is supported by public funding from the Catalan Health Service, Department of Health, Generalitat de Catalunya.

Conflict of interestsNone.

The authors thank Jaume Clapés and Jaume Casas (Information Systems of Catalan Health Service) for the program for data collection.

Members of VINCat Program Group: P. Alemany, P. Arcenillas, T. Arranz, A. Ayestarán, A. Balet, M.T. Barrera, N. Benages, R. Borràs, N. Bosacoma, D. Brandariz, M. Calafell, J.M. Calbet, M. Calonge, D. Campany, L. Campins, L. Canadell, S.M. Cano, P. Capdevila, A. Capellà, N. Carrasco, M. Carrascosa, J. Cuquet, O. Curiel, G. Enrique-Tarancon, M. Espona, J. Fernández, E. Fernández de Gamarra, J. Fierro, E. Flotats, M.J. Fraile, I. Frigola, M. Fuster, G. Gayolà, R. Gil, V. Gol, A. Gómez, L. Gratacós, M. Grañó, L. Ibañez, E. Julian, E. López-Suñé, U. Manso, P. Marcos, I. Martínez, N. Miserachs, M. Montserrat, A. Morón, L. Munell, E. Ódena, N. Ortí, A. Padullés, F. Páez, B. Pascual, M. Pineda, M. Pons, F. Pujol, N. Quer, L. Salse, J. Serrais, S. Terré, C. Valls, E. Vicente, M.A. Vidal.