Infectious mononucleosis (IM) is a common entity caused by different aetiological agents. The one that accounts for the most cases (90% of them) is Epstein–Barr virus (EBV). In children, primary infection usually goes unnoticed. In young adults, it is more symptomatic, featuring a typical triad of fever, cervical lymphadenopathy and odynophagia.1

Usually it is a self-limiting disease requiring treatment of symptoms. However, its duration and seriousness may vary considerably.1 Complications are rare in immunocompetent adults. An increased incidence of serious cases of IM has recently been reported.2

We present a case of IM due to EBV with acute mediastinitis as a rare complication.

A 22-year-old woman, an active smoker with a penicillin allergy and no other prior history of interest, was admitted to our hospital due to signs and symptoms consistent with IM (general malaise, fever, myalgia and odynophagia). A physical examination revealed cervical lymphadenopathy, jaundice, splenomegaly and tonsillar hypertrophy with necrosis.

Laboratory testing revealed abnormal liver function tests (bilirubin 4.10mg/dl; AST 458U/l; ALT 831U/l; AP 438U/l and GGT 384U/l), peripheral blood leukocytosis (14,990×109/l) at the expense of lymphocytes (29%) and high C-reactive protein (316mg/l). Blood cultures and serologies for cytomegalovirus; herpesvirus 6, parvovirus B19; toxoplasmosis; hepatitis A, B and C; and human immunodeficiency virus were negative. However, IgM antibodies for EBV were positive (IgG antibodies were negative) and a lymphogram showed an abnormal CD4/CD8 ratio (20%/57%). Quantification of immunoglobulins showed no deficit and an abdominal ultrasound confirmed splenomegaly measuring 15.8cm.

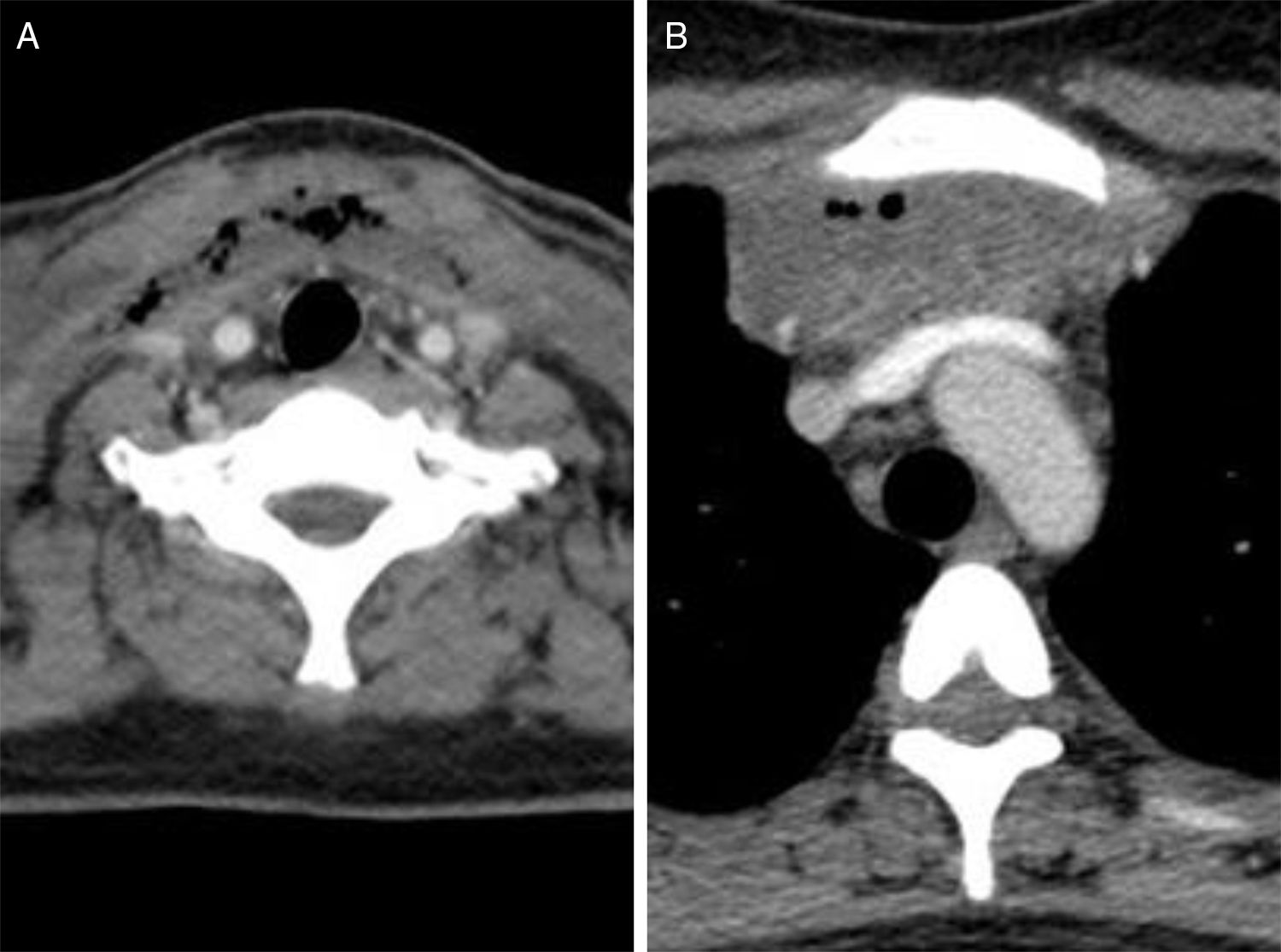

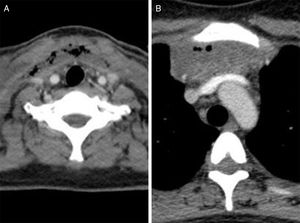

After 7 days had elapsed since the patient's admission, due to persistent fever and progressive dysphagia as well as onset of oedema in the submandibular and anterior cervical area, the patient underwent a cervical ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) scan (Fig. 1). This showed hypertrophic tonsils as well as collections of air and fluid in the anterior laterocervical and supraclavicular area having spread to subcutaneous fat tissue and deep spaces. Given the patient's penicillin allergy and a suspicion of serious infection, broad-spectrum empirical antibiotic therapy (imipenem) and intravenous corticosteroid therapy were started.

Due to a suspicion of spread to the mediastinum, a chest CT scan was performed (Fig. 1). This confirmed an anterior mediastinal collection measuring 70mm×70mm with images of air and septa inside requiring subdrainage through 2 cervicotomies. Both were done under orotracheal intubation. This intubation had to be prolonged due to oedema of the airway, and the patient had to be admitted to the intensive care unit.

Varied flora with a predominance of Streptococcus anginosus and Bacillus spp. were isolated from the cultures of the surgical samples. Following her second surgery, the patient followed a good clinical course with good laboratory values. She completed 4 weeks of antibiotic therapy and had outpatient check-ups with no signs of complications or sequelae.

The seroprevalence of EBV may vary by geographic area, and primary infection appears at younger ages in developing areas.3 The virus is transmitted through saliva. Transmission through blood or through transplantation of a solid organ or hematopoietic stem cells is less common.3 The risk of developing IM in primary EBV infection is linked to age, and is higher in adolescents and young adults. Primary infection in patients over 40 years of age carries a higher risk of complications.3

Septic complications due to bacterial superinfection are rare (<1%) and may present in the form of pharyngeal abscess, pneumonia (often related to Mycoplasma), septic thrombophlebitis or empyema.4

Cases of AM have been reported in the literature.4–7 The patients at highest risk of developing this complication are believed to be those who present a retropharyngeal abscess due to invasion of the mediastinum and pleural space through the prevertebral fascia as well as those who present septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein (Lemierre's syndrome) with secondary septic embolisms.4

Unlike in reported cases, our patient developed an anterior cervical abscess with direct spread to the mediastinum. Her CT scan showed neither a peritonsillar nor a retropharyngeal abscess. It also did not show venous thrombophlebitis to be the origin of her signs and symptoms. In addition, she did not exhibit any immunosuppression.

In conclusion, we report a case of IM with a very rare but serious and potentially life-threatening complication. Given the clinical suspicion, a targeted imaging test was required, as making an early diagnosis is essential for starting suitable treatment.8

Please cite this article as: Clotet S, Matas L, Pomar V, Casademont J. Mediastinitis aguda como complicación atípica de una mononucleosis infecciosa. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2018;36:602–603.