Antimicrobial defined daily dose (DDD), a standardized metric to assess antimicrobial consumption in adult population, has limitations hampering its use in neonatal patients. This study proposes an alternative DDD design applicable for neonates.

MethodsNeonates (<1 month-old) from 6 Spanish hospitals during a 12-months period were included. Weight and weeks gestational age of each neonate were the variables collected. DDD (g) for each antimicrobial was calculated by multiplying the obtained weight times the recommended dose (mg/kg) of the antimicrobial for the most common infectious indication selected by the Delphi method.

ResultsA total of 4820 neonates were included. Mean age was 36.72 weeks of gestational age and Mean weight was 2.687kg. Standardized DDD (intravenous; oral route) for representative antimicrobials were: Amoxicillin (0.08; 0.08), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (0.27; 0.08), ampicillin (0.27; x), cloxacillin (0.13; 0.13), penicillin G sodium (0.12), cefazolin (0.13), cefuroxime (0.27; x), cefotaxime (0.27), ceftazidime (0.27), ceftriaxone (0.13), cefepime (0.27) piperacillin-tazobactam (0.54), aztreonam (0.24), azithromycin (0.03; 0.03), clindamycin (0.04; 0.04), amikacin (0.04), gentamicin (0.01), metronidazole (0.04; 0.08), ciprofloxacin (0.04; 0.05), levofloxacin (x;x), fluconazole (0.02; 0.02), itraconazole (0.01; 0.01), fosfomycin (0.27). Restricted antimicrobials: meropenem (0.11), teicoplanin (0.02), vancomycin (0.08; 0.11), linezolid (0.08; 0.08), daptomycin (x), amphotericin B liposomal (0.01).

ConclusionsA useful method for antimicrobial DDD measurement in neonatology has been designed to monitor antimicrobial consumption in hospital settings. It should be validated in further studies and thereby included in the design for neonatal antimicrobial stewardship programs in the future.

La dosis diaria definida de antimicrobianos (DDD), un método estandarizado para evaluar el consumo de antimicrobianos en la población adulta, tiene limitaciones que dificultan su uso en la población neonatal. Este estudio propone un diseño alternativo de la DDD aplicable a los recién nacidos.

MétodosSe incluyeron neonatos (<1 mes) de 6 hospitales españoles durante un período de 12 meses. El peso y las semanas de edad gestacional de cada recién nacido fueron las variables recogidas. Las DDD (g) de cada antimicrobiano se calcularon multiplicando el peso obtenido por la dosis recomendada (mg/kg) del antimicrobiano para la indicación infecciosa más común seleccionada por el método Delphi.

ResultadosSe incluyeron un total de 4.820 recién nacidos. La edad media fue de 36,72 semanas de edad gestacional y el peso medio fue de 2,687kg. La DDD estandarizado (intravenoso; oral) para antimicrobianos seleccionados fueron: amoxicilina (0,08; 0,08), amoxicilina-ácido clavulánico (0,27; 0,08), ampicilina (0,27; x), cloxacilina (0,13; 0,13), penicilina G sódica (0,12), cefazolina (0,13), cefuroxima (0,27; x), cefotaxima (0,27), ceftazidima (0,27), ceftriaxona (0,13), cefepima (0,27) piperacilina-tazobactam (0,54), aztreonam (0,24), azitromicina (0,03; 0,03) clindamicina (0,04; 0,04), amikacina (0,04), gentamicina (0,01), metronidazol (0,04; 0,08), ciprofloxacina (0,04; 0,05), levofloxacina (x; x), fluconazol (0,02; 0,02), itraconazol (0,01; 0,01), fosfomicina (0,27). Antimicrobianos restringidos: meropenem (0,11), teicoplanina (0,02), vancomicina (0,08; 0,11), linezolid (0,08; 0,08), daptomicina (x), anfotericina B liposomal (0, 01).

ConclusionesSe ha diseñado un método útil para la medición de las DDD de antimicrobianos en neonatología para controlar el consumo de antimicrobianos en entornos hospitalarios. Debería validarse en estudios posteriores para incluirse en el diseño de los programas de administración de antimicrobianos neonatales en el futuro.

In clinical practice, antimicrobials are among the most commonly prescribed drugs in the hospital setting.1 In neonates, infectious pathology is frequent, especially in premature infants, immunologically vulnerable and exposed to risks.2 The diagnosis for suspected infection is difficult, however, in case of suspected sepsis, the early onset of antibiotic therapy leads to a better prognosis, thus favoring the use of antibiotic therapies empirically. Between 30–50% of infants admitted to Neonatology receive one or several antibiotic cycles, especially in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). The consequences of the use of antibiotics occur both individually and in the environment since exposure of the newborn to antibiotics after birth causes deviation from normal colonization patterns with impaired diversity and impoverishment of the intestinal microbiota.3–6 These differences may persist for up to one year.

Despite the development of new generations of antibiotics, adequate use of existing antibiotics is needed to ensure the long-term availability of effective treatment for bacterial infections.7,8 If antibiotics become ineffective, established and recently emerging infectious diseases are becoming a growing threat, they can lead to increased morbidity, use of medical care and premature mortality.8,9

Antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASP) have been successfully implemented to optimize antimicrobial use in hospitalized patients, to improve the clinical results of infected patients, to minimize the adverse effects associated with antimicrobial use and to ensure a cost-effective therapy.10 To date, development of ASP in neonatal patients have been limited, due in part to the lack of a standardized method for comparing antimicrobial.11 DDD is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the average standard daily dose of a drug used in a 70kg adult for the most common indication.12,13 However, the validity of the WHO definition of DDD is questionable in hospitalized newborns, in which dosing is adjusted for body weight.1,13 This study aims to establish a methodology for the measurement of antimicrobial DDD in the neonatal population.

MethodsSelection of antibiotic included and dose consensus usedIn the agreement process for the recommended antimicrobial doses for the most common indications for each antimicrobial, ten Spanish hospitals (9 third level and 1 second level) and twenty experts (one pharmacist and one pediatric infectious diseases specialist from each participating center) participated. The usual indication was considered to be one for which the antibiotic was routinely prescribed considering the clinical practice indications. The Delphi method was used to find a joint agreement. This method is a structured process that uses a series of questionnaires or “rounds” to collect information, which are retained until the consensus of the group is reached.14 In case of disagreement after a second round, the antimicrobial dose was established using the Database of Medicines Committee of the Spanish Association of Pediatrics (Pediamecum®).15

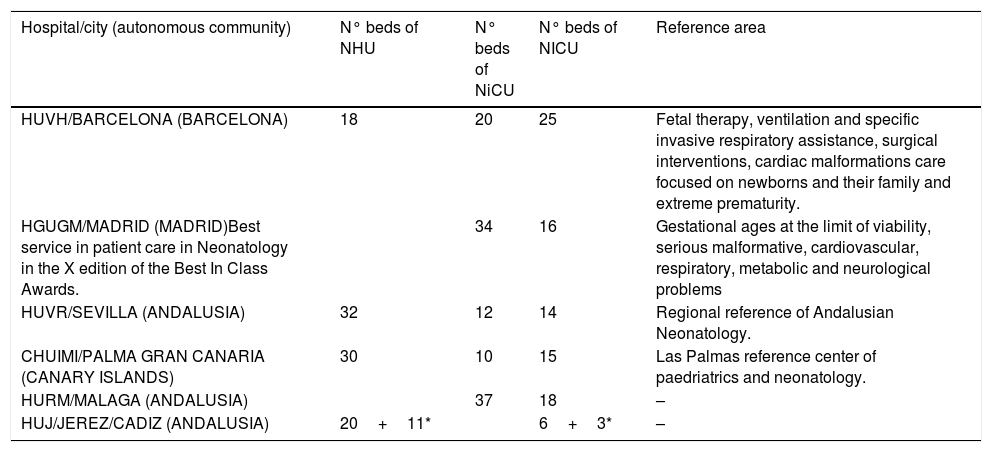

Study populationSubsequently, an observational retrospective multicentre study was performedNeonatal patients (<1 month old) from 6 tertiary Spanish hospitals, with at least one episode of hospital admission into a neonatal ward, during a 12-months period (January to December 2018) were included. The hospitals are distributed geographically all over Spain: three in Andalusia, one in Madrid, one in Barcelona and one hospital in the Canary Islands. All of them have a neonatology service whith NICU and in three of them this service is a reference of their autonomous community. The characteristics of the hospitalary centers are detailed in Table 1.

Characteristics of hospitals.

| Hospital/city (autonomous community) | N° beds of NHU | N° beds of NiCU | N° beds of NICU | Reference area |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HUVH/BARCELONA (BARCELONA) | 18 | 20 | 25 | Fetal therapy, ventilation and specific invasive respiratory assistance, surgical interventions, cardiac malformations care focused on newborns and their family and extreme prematurity. |

| HGUGM/MADRID (MADRID)Best service in patient care in Neonatology in the X edition of the Best In Class Awards. | 34 | 16 | Gestational ages at the limit of viability, serious malformative, cardiovascular, respiratory, metabolic and neurological problems | |

| HUVR/SEVILLA (ANDALUSIA) | 32 | 12 | 14 | Regional reference of Andalusian Neonatology. |

| CHUIMI/PALMA GRAN CANARIA (CANARY ISLANDS) | 30 | 10 | 15 | Las Palmas reference center of paedriatrics and neonatology. |

| HURM/MALAGA (ANDALUSIA) | 37 | 18 | – | |

| HUJ/JEREZ/CADIZ (ANDALUSIA) | 20+11* | 6+3* | – |

NHU: Neonatal Hospitalized Unit, NiCU: Neonatal intermediate Care Unit, NICU: Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. HUVH: Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron, HGUGM: Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón, HUVR: Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, HURM: Hospital Universitario Regional de Malaga, CHUIMI: Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Insular Materno-Infantil. HUJ: Hospital universitario Jerez de la Frontera.

Each patient hospital admission was considered an “episode”(independently whether or not antibiotic therapy was initiated). For the study purposes, different hospital admissions through the study period and/or change of in-hospital ward during the same hospital admission period were considered as different episodes. Studied variables were weight and weeks of gestational age. These demographic characteristics were obtained through the hospitals’ admission or clinical history register of each hospital.

Data analysisRegarding the agreed doses of antibiotic, the percentage of concordance was calculated using the number of hospitals that selected the agreed dose as numerator and the number of hospitals that proposed a dose as denominator. The mean, median, standard deviation, maximum and minimum of demographic characteristics were calculated. In addition for the weight variable, the global coefficient of variation and the coefficient of variation of each centers was calculated.

The neonatal DDD (g) for each antimicrobial was calculated, by multiplying the total average weight of the cohort (kg) and the recommended dose for the most common indication of each antimicrobial (mg per kg) previously agreed.

Data analysis was performed using the SPSS statistical software, version 19 (IBM SPSS, Armonk, New York).

EthicsThe study was approved by the Spanish Agency for Medicines and Sanitary Products. It was classified as “Post-authorization study with other designs different from prospective design” on May 11th, 2015 (ID number: GAT-TEI-2015-01). Subsequently, it was approved by the Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío and Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena Ethics Committee on October 24th, 2016, (ID number: 0620-N-15).

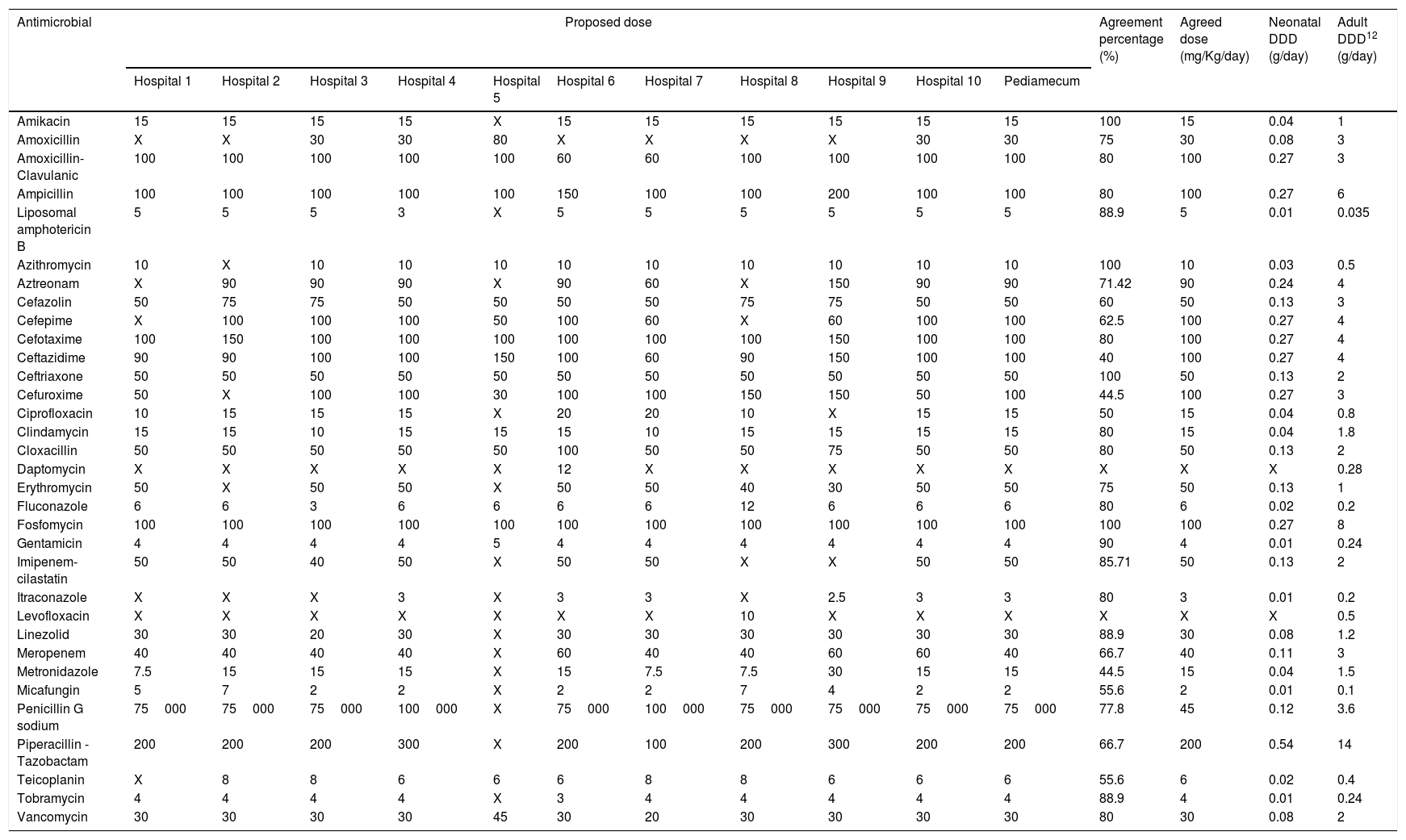

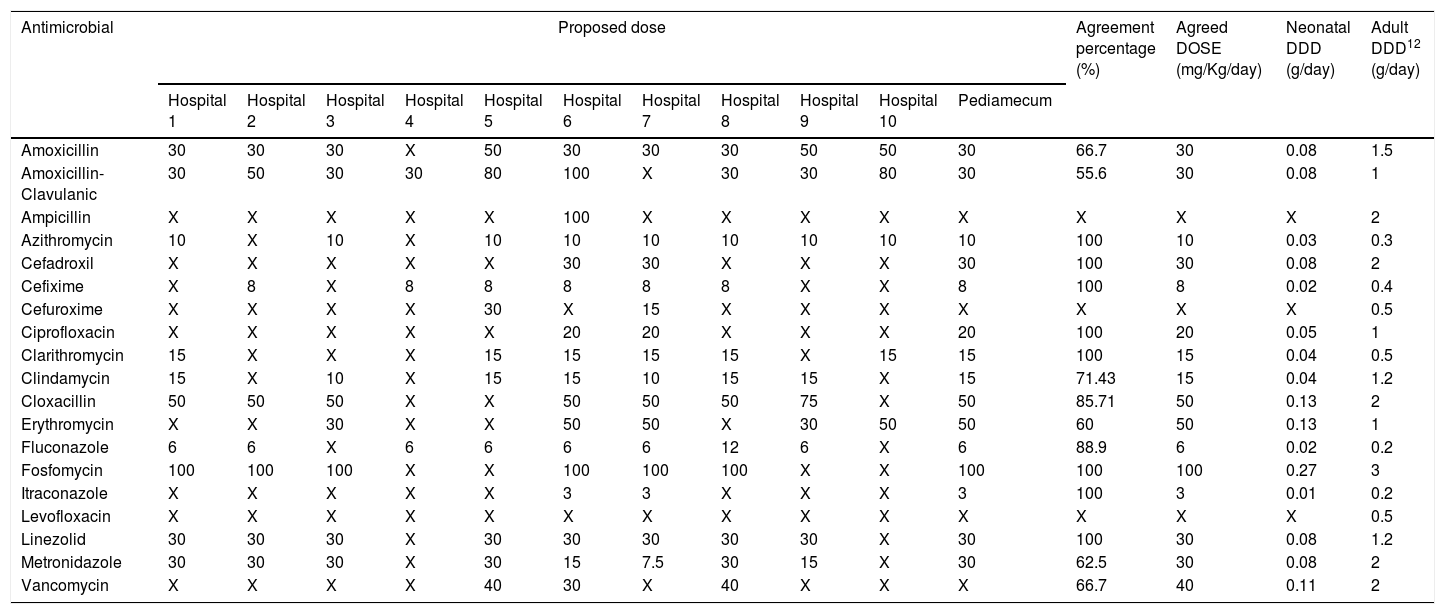

ResultsThe selected antimicrobials with their respective calculated DDDs and agreement percentages are shown in Table 2 (intravenous route) and Table 3 (oral route). In 11 out of 52 evaluated antimicrobials, a second round was necessary for dose agreement, achieving it in 4 of them. In the other, 2 doses were agreed using data from Pediamecum and the remaining 5 were discarded because they were not used in neonatology in the usual clinical practice. Total agreement percentage was 77.09% (286/371): 75.27% (207/275) and 82.29% (79/96) for intravenous and oral antimicrobials, respectively. The corresponding DDD of adult patients are included in both tables.

Neonatology defined daily dose of intravenously administered antimicrobials according to the results of Delphi method.

| Antimicrobial | Proposed dose | Agreement percentage (%) | Agreed dose (mg/Kg/day) | Neonatal DDD (g/day) | Adult DDD12 (g/day) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital 1 | Hospital 2 | Hospital 3 | Hospital 4 | Hospital 5 | Hospital 6 | Hospital 7 | Hospital 8 | Hospital 9 | Hospital 10 | Pediamecum | |||||

| Amikacin | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | X | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 100 | 15 | 0.04 | 1 |

| Amoxicillin | X | X | 30 | 30 | 80 | X | X | X | X | 30 | 30 | 75 | 30 | 0.08 | 3 |

| Amoxicillin-Clavulanic | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 60 | 60 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 80 | 100 | 0.27 | 3 |

| Ampicillin | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 150 | 100 | 100 | 200 | 100 | 100 | 80 | 100 | 0.27 | 6 |

| Liposomal amphotericin B | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | X | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 88.9 | 5 | 0.01 | 0.035 |

| Azithromycin | 10 | X | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 100 | 10 | 0.03 | 0.5 |

| Aztreonam | X | 90 | 90 | 90 | X | 90 | 60 | X | 150 | 90 | 90 | 71.42 | 90 | 0.24 | 4 |

| Cefazolin | 50 | 75 | 75 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 75 | 75 | 50 | 50 | 60 | 50 | 0.13 | 3 |

| Cefepime | X | 100 | 100 | 100 | 50 | 100 | 60 | X | 60 | 100 | 100 | 62.5 | 100 | 0.27 | 4 |

| Cefotaxime | 100 | 150 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 150 | 100 | 100 | 80 | 100 | 0.27 | 4 |

| Ceftazidime | 90 | 90 | 100 | 100 | 150 | 100 | 60 | 90 | 150 | 100 | 100 | 40 | 100 | 0.27 | 4 |

| Ceftriaxone | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 100 | 50 | 0.13 | 2 |

| Cefuroxime | 50 | X | 100 | 100 | 30 | 100 | 100 | 150 | 150 | 50 | 100 | 44.5 | 100 | 0.27 | 3 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 10 | 15 | 15 | 15 | X | 20 | 20 | 10 | X | 15 | 15 | 50 | 15 | 0.04 | 0.8 |

| Clindamycin | 15 | 15 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 80 | 15 | 0.04 | 1.8 |

| Cloxacillin | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 75 | 50 | 50 | 80 | 50 | 0.13 | 2 |

| Daptomycin | X | X | X | X | X | 12 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.28 |

| Erythromycin | 50 | X | 50 | 50 | X | 50 | 50 | 40 | 30 | 50 | 50 | 75 | 50 | 0.13 | 1 |

| Fluconazole | 6 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 12 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 80 | 6 | 0.02 | 0.2 |

| Fosfomycin | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0.27 | 8 |

| Gentamicin | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 90 | 4 | 0.01 | 0.24 |

| Imipenem-cilastatin | 50 | 50 | 40 | 50 | X | 50 | 50 | X | X | 50 | 50 | 85.71 | 50 | 0.13 | 2 |

| Itraconazole | X | X | X | 3 | X | 3 | 3 | X | 2.5 | 3 | 3 | 80 | 3 | 0.01 | 0.2 |

| Levofloxacin | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 10 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.5 |

| Linezolid | 30 | 30 | 20 | 30 | X | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 88.9 | 30 | 0.08 | 1.2 |

| Meropenem | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | X | 60 | 40 | 40 | 60 | 60 | 40 | 66.7 | 40 | 0.11 | 3 |

| Metronidazole | 7.5 | 15 | 15 | 15 | X | 15 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 30 | 15 | 15 | 44.5 | 15 | 0.04 | 1.5 |

| Micafungin | 5 | 7 | 2 | 2 | X | 2 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 55.6 | 2 | 0.01 | 0.1 |

| Penicillin G sodium | 75000 | 75000 | 75000 | 100000 | X | 75000 | 100000 | 75000 | 75000 | 75000 | 75000 | 77.8 | 45 | 0.12 | 3.6 |

| Piperacillin - Tazobactam | 200 | 200 | 200 | 300 | X | 200 | 100 | 200 | 300 | 200 | 200 | 66.7 | 200 | 0.54 | 14 |

| Teicoplanin | X | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 55.6 | 6 | 0.02 | 0.4 |

| Tobramycin | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | X | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 88.9 | 4 | 0.01 | 0.24 |

| Vancomycin | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 45 | 30 | 20 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 80 | 30 | 0.08 | 2 |

Abbreviations: DDD: Defined daily dose; X: not used.

Hospital 1: Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla; Hospital 2: Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga; Hospital 3: Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de A Coruña; Hospital 4: Hospital Universitario Cruces, Baracaldo; Hospital 5: Hospital Universitario Infanta Sofía, Madrid; Hospital 6: Complejo Hospitalaria Universitario Insular Materno-Infantil, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria; Hospital 7: Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía, Córdoba; Hospital 8: Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid; Hospital 9: Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebrón, Barcelona; Hospital 10: Hospital Universitario de Jerez, Cádiz.

Neonatology defined daily dose of orally administered antimicrobials according to the results of Delphi method.

| Antimicrobial | Proposed dose | Agreement percentage (%) | Agreed DOSE (mg/Kg/day) | Neonatal DDD (g/day) | Adult DDD12 (g/day) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital 1 | Hospital 2 | Hospital 3 | Hospital 4 | Hospital 5 | Hospital 6 | Hospital 7 | Hospital 8 | Hospital 9 | Hospital 10 | Pediamecum | |||||

| Amoxicillin | 30 | 30 | 30 | X | 50 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 50 | 50 | 30 | 66.7 | 30 | 0.08 | 1.5 |

| Amoxicillin-Clavulanic | 30 | 50 | 30 | 30 | 80 | 100 | X | 30 | 30 | 80 | 30 | 55.6 | 30 | 0.08 | 1 |

| Ampicillin | X | X | X | X | X | 100 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 2 |

| Azithromycin | 10 | X | 10 | X | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 100 | 10 | 0.03 | 0.3 |

| Cefadroxil | X | X | X | X | X | 30 | 30 | X | X | X | 30 | 100 | 30 | 0.08 | 2 |

| Cefixime | X | 8 | X | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | X | X | 8 | 100 | 8 | 0.02 | 0.4 |

| Cefuroxime | X | X | X | X | 30 | X | 15 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.5 |

| Ciprofloxacin | X | X | X | X | X | 20 | 20 | X | X | X | 20 | 100 | 20 | 0.05 | 1 |

| Clarithromycin | 15 | X | X | X | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | X | 15 | 15 | 100 | 15 | 0.04 | 0.5 |

| Clindamycin | 15 | X | 10 | X | 15 | 15 | 10 | 15 | 15 | X | 15 | 71.43 | 15 | 0.04 | 1.2 |

| Cloxacillin | 50 | 50 | 50 | X | X | 50 | 50 | 50 | 75 | X | 50 | 85.71 | 50 | 0.13 | 2 |

| Erythromycin | X | X | 30 | X | X | 50 | 50 | X | 30 | 50 | 50 | 60 | 50 | 0.13 | 1 |

| Fluconazole | 6 | 6 | X | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 12 | 6 | X | 6 | 88.9 | 6 | 0.02 | 0.2 |

| Fosfomycin | 100 | 100 | 100 | X | X | 100 | 100 | 100 | X | X | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0.27 | 3 |

| Itraconazole | X | X | X | X | X | 3 | 3 | X | X | X | 3 | 100 | 3 | 0.01 | 0.2 |

| Levofloxacin | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.5 |

| Linezolid | 30 | 30 | 30 | X | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | X | 30 | 100 | 30 | 0.08 | 1.2 |

| Metronidazole | 30 | 30 | 30 | X | 30 | 15 | 7.5 | 30 | 15 | X | 30 | 62.5 | 30 | 0.08 | 2 |

| Vancomycin | X | X | X | X | 40 | 30 | X | 40 | X | X | X | 66.7 | 40 | 0.11 | 2 |

Abbreviations: DDD: Defined daily dose; X: not used.

Hospital 1: Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla; Hospital 2: Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga; Hospital 3: Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de A Coruña; Hospital 4: Hospital Universitario Cruces, Baracaldo; Hospital 5: Hospital Universitario Infanta Sofía, Madrid; Hospital 6: Complejo Hospitalaria Universitario Insular Materno-Infantil, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria; Hospital 7: Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía, Córdoba; Hospital 8: Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid; Hospital 9: Hospital Universitario Vall D’Hebrón, Barcelona; Hospital 10: Hospital Universitario de Jerez, Cádiz.

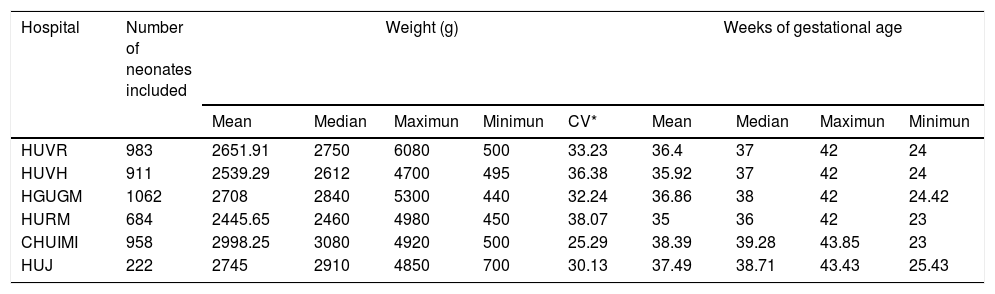

In the observational study, a total of 4820 neonatal patients were included. The mean gestational age calculated was 36.72 weeks (SD±3.96; Max=43.85; Min=23) and median was 37.71 weeks; the mean weight was 2.687kg. (SD±0.887; Max=6.080; Min=0.440; CV=33.01) and median was 2.810 Kg. The demographic characteristics of neonates included are detailed in Table 4.

Demographics characteristics of neonates included.

| Hospital | Number of neonates included | Weight (g) | Weeks of gestational age | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Maximun | Minimun | CV* | Mean | Median | Maximun | Minimun | ||

| HUVR | 983 | 2651.91 | 2750 | 6080 | 500 | 33.23 | 36.4 | 37 | 42 | 24 |

| HUVH | 911 | 2539.29 | 2612 | 4700 | 495 | 36.38 | 35.92 | 37 | 42 | 24 |

| HGUGM | 1062 | 2708 | 2840 | 5300 | 440 | 32.24 | 36.86 | 38 | 42 | 24.42 |

| HURM | 684 | 2445.65 | 2460 | 4980 | 450 | 38.07 | 35 | 36 | 42 | 23 |

| CHUIMI | 958 | 2998.25 | 3080 | 4920 | 500 | 25.29 | 38.39 | 39.28 | 43.85 | 23 |

| HUJ | 222 | 2745 | 2910 | 4850 | 700 | 30.13 | 37.49 | 38.71 | 43.43 | 25.43 |

HUVH: Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebrón, HGUGM: Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón, HUVR: Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, HURM: Hospital Universitario Regional de Malaga, CHUIMI: Complejo Hospitalaria Universitario Insular Materno-Infantil. HUJ: Hospital Universitario de Jerez de la Frontera.

The analysis of the data shows consensus and relationship between the variables, weight and gestational age of neonates admitted in the six hospitals included. The data of median and average weight of the hospitals match, which shows the homogeneous characteristics of the sample of neonates studied.

Most of the neonatal studies found in the literature are focused on determining the effectiveness of the implementation of antibiotic policies, descriptive studies on the qualitative use of antimicrobials as well as multi-resistance studies, however we lack validated methods of antimicrobial consumption.16–18 Few studies have used the DDD methodology in neonates.19 Portas et al. develop a new standardized way of comparing rates of antimicrobial prescribing between four European children's hospitals (The United Kingdom, Greece and Italy) whose complexity and number of beds resembles the centers of our National study. The median age was 24.4 days (IQR 1–205 days) for neonates (In our case we study gestational age not postnatal age). The methodology uses three phases; 1st comparison of the proportion of hospitalized children on antibiotics by weight bands (<10kg, 10–25kg, >25kg) and the number of antimicrobials that account for 90% of total DDD drug usage (DU90%). 2nd comparison of the dosing used (mg/kg/day) and 3rd compare overall drug exposure using DDD/100 bed days for standardized weight bands between centers. However, this method requires validation in a large prospective study of punctual prevalence that has not been published.

A systematic review20 found up to 26 distinct measures across 79 studies (DDD or similar metrics in 38 studies). Of all of them, only 47 on the pediatric and neonatal population and 5 studies21–26 comparing different measures of antimicrobial use. Limitations were found for all metrics and authors conclude that the best metric remains to be identified.

Regarding references on demografic characteristics of the neonatal, the study conducted by Suryawanshi et al.27 on antibiotic prescribing pattern in a tertiary level neonatal Intensive Care Unit in Western Maharashtra, showed data of 528 neonates included in the study whose mean gestational age was 35 weeks (SD±3.2, minimum=23, maximum=42) and the mean birth weight was 2.0kg. (SD±0.7, minimum 0.5kg, maximum 4.0kg). Distrasakou et al.28 in a NICU in a Maternity hospital in Athen, which included 252 hospitalized infants recived antibiotics whose mean birth weight was 2.7kg. All of them show values close to ours of 36.68 weeks of gestational age and mean weight was 2.685kg.

Regarding references on design of a more specific consumption measure Liem et al.29 proposed a set of neonatal DDD for ten antibiotics commonly used in neonates based on a standardized neonatal weight. The standard dose for each antibiotic was selected after comparison of 8 different sources of information both Netherlands and American reference for pediatrics and consult two external experts. A mean weight of 2.1±1kg was established according to the data of the researchers and calculates the DDD of 10 antibiotics Ampicillin (0.2), Amoxicillin (0.2), Amoxicillin plus Acid Clavulanic (0.2), Ceftazidime (0.3), Cefotaxime (0.3), Meropenem (0.12), Erythromycin (0.06), Gentamicin (0.08) and Vancomycin (0.06) according to that weight obtaining. DDD values close to those proposed in our study in case of vancomycin (0.08), Gentamicin (0.01), Meropenem (0.11), Cefotaxime (0.27), Ceftazidime (0.27), Ampicilin (0.27) and Amoxicilin clavulanic (0.27). However, there are differences with DDD for Erythromycin (0.13), where the consensual dose considered is 50mg instead of 30mg of Liem and for Amoxicilln (0.08) with consensus doses are lower than those of Netherlands study (30mg vs. 75mg).

Main limitations of our study include the lack of validation of this strategy and low external validity of the method. To overcome this, a new multicentre study has been projected to validate this tool in real-life patients who receives antimicrobial prescriptions under usual clinical practice. Currently, the project is looking for internal validity in our country. If good results are obtained, further international multi-center studies will be proposed in order to study variables such as race, weight ranges, gestational age … in order to be able to standardize this metric internationally.13

This study is the only one that has established a consensus on the doses used in each of the selected antibiotics through a group of multidisciplinary experts from different hospitals. This aspect is of great relevance due to the wide variability of doses used in clinical practice in neonatology. In addition, this study provides one of the largest sample size to define specific DDD for neonatal in a multicentre setting: more than 4500 infants with real data of weight and gestational age of several hospitals in Spain whose distribution includes a representation of the Spanish territory.

This study has designed a neonatal DDD for antimicrobial consumption assessment. Further validation of this tool is required in future studies as this metric could help to design neonatal ASP strategies to prevent the emergence and dissemination of antimicrobial resistance in children.

FundingNo specific funding was received for this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.