To assess the characteristics of suspected coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) and the rate of confirmed COVID-19 in a pediatric population at the beginning of the pandemic in Portugal.

Study designSuspected COVID-19 pediatric cases that were tested in a Portuguese hospital between March 17 and April 2 2020 were included in this descriptive retrospective study. The analyzed data included socio-demographic parameters, characteristics of the household, underlying medical conditions and symptoms.

ResultsNinety-four patients were included and all of them were symptomatic and treated without hospitalization. The most common symptoms were cough (80%;n=75), rhinorrhea (72%;n=68) and fever (60%;n=56). There was only one positive for SARS-CoV-2 in a five-year-old child with mild illness without epidemiologic linkage.

ConclusionThis study showed a low rate of confirmed COVID-19 in children. The causes for this low rate can be multifactorial and illustrates how differently this virus spreads in the pediatric population.

Evaluar las características en casos sospechosos y la tasa de casos confirmados de enfermedad por coronavirus 19 (COVID-19) en una población pediátrica al inicio de la pandemia en Portugal.

MétodosEn este estudio descriptivo-retrospectivo se incluyeron casos pediátricos sospechosos de COVID-19 que se testearon en un hospital portugués entre el 17 de marzo y el 2 de abril de 2020. Los datos fueron analizados bajo parámetros sociodemográficos, características del hogar, condiciones médicas subyacentes y síntomas.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 94 pacientes, todos sintomáticos y tratados sin hospitalización. Los síntomas más frecuentes fueron tos (80%; n=75), rinorrea (72%; n=68) y fiebre (60%; n=56). Solo hubo un caso positivo para SARS-CoV-2, un niño de 5 años con una enfermedad leve, sin vínculo epidemiológico.

ConclusiónEste estudio mostró una baja tasa de casos confirmados de COVID-19 en niños. Las causas de esta baja tasa pueden ser multifactoriales e ilustran cuán diferente se propaga este virus en la población pediátrica.

In December 2019, Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was described in China and quickly spread across the world. On 11 March a pandemic was declared by World Health Organization. The first case in Portugal was confirmed on March 2 and 16 days later a state of emergency was declared that allowed establishing exceptional measures to prevent the transmission of the virus.

As of April 2, the SARS-CoV-2 had been responsible for more than 896450 infections and 45525 deaths worldwide.1 On that day, in Portugal, there were 9034 cases, 334 up to 19 years old (3.7%), with no deaths recorded in this age group.2

In a report by United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, among 149082 COVID-19 cases reported as of April 2, only 1.7% occurred in patients aged<18 years. In addition, 73% of pediatric patients had symptoms of fever, cough or shortness of breath. This report also found a much higher percentage of adults hospitalized and admitted to the Intensive care units compared with children.3

In another study, 18 individuals (9 students and 9 staff) from fifteen New South Wales schools were diagnosed with COVID-19. Of the 863 close contacts of these positive cases, only two students may have contracted COVID-19 from the initial COVID-19 cases at their schools.4 This supports previous research from different countries showing that children have probably a lower susceptibility to infection and have a less severe disease and suggested a limited spread among children and from children to adults.5,6

Our study aim is to understand the rate and spread of SARS-CoV-2 in a pediatric population in the beginning of the pandemic in Portugal.

Study designHospital Prof. Doutor Fernando Fonseca is a district Hospital in the region of Amadora and Sintra, corresponding to a total population of 568069 people with 90761 children under 15 years old,7 with a pediatric emergency department that receives a mean 160 children per day (under 18 years old).

In the period considered, COVID-19 tests were performed in children that attended our emergency department according to the criteria of the Portuguese health ministry.8 Children who were symptomatic (cough, fever, myalgias or shortness of breath) and had been in regions classified as high-risk transmission by the health authorities, or who had been in contact with infected people were included. Children were defined as being<18 years old.

This descriptive retrospective cross-sectional study was carried out between March 17 and April 2, 2020 by consulting computerized clinical files and performing follow-up questionnaires that were allowed by verbal consent of the legal guardians. At the beginning of the pandemic, a follow-up protocol was established in the Pediatrics Department of our hospital for children with suspected COVID-19 who attended our emergency department. This follow-up was performed by a pediatrician, who performed phone calls to give the result of the COVID-19 test (between 12 and 24h after admission) and to monitor the clinical evolution of the disease.

Nasopharyngeal and throat swabs were obtained for detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA using VIASURE SARS-CoV-2S gene Real Time PCR Detection Kit (Quilaban®) that has a detection limit of ≥24 cDNA copies per reaction with a positive rate of ≥95% using real time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay.

The analyzed data included socio-demographic parameters, characteristics of the household (professions, development of COVID-19 symptoms, performance of COVID-19 test and compliance to social isolation), underlying medical conditions and symptom characterization (presence of fever, cough, rhinorrhea, shortness of breath, among others).

This study was approved by the hospital's ethics committee. Data were deidentified for the researchers.

Statistical analysis was performed in Excel Microsoft 365, 2020 Microsoft Corporation©.

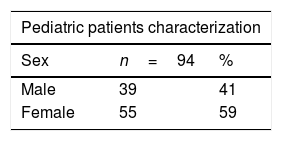

ResultsIn the study period, 94 patients were tested for COVID-19 and all of them were symptomatic. No patient needed to be hospitalized. Fifty-five children were female (59%). The median age was 11 years old (IQR: 1–13). Twenty children (21%) had at least one underlying disease (Table 1).

Pediatric patients screened in the community of Amadora-Sintra, Portugal.

| Pediatric patients characterization | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sex | n=94 | % |

| Male | 39 | 41 |

| Female | 55 | 59 |

| Underlying conditions | n=21 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Asthma | 10 | 47.6 |

| Recurrent wheezing | 3 | 14.3 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 2 | 9.5 |

| Arrythmia | 1 | 4.8 |

| Cardiopathy | 1 | 4.8 |

| Biliary atresia | 1 | 4.8 |

| Epilepsy | 1 | 4.8 |

| Primary ciliary dyskinesia | 1 | 4.8 |

| Immune thrombocytopenia purpura | 1 | 4.8 |

| Indication to perform the test | n=94 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | 69 | 73.4 |

| Symptoms and underlying disease | 20 | 21.3 |

| Symptoms and risk contact with a COVID-19 confirmed person | 5 | 5.3 |

| Symptoms | n=94 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Cough | 75 | 80 |

| Rhinorrhea | 68 | 72 |

| Fever | 56 | 60 |

| Sore throat/oropharynx hyperemia | 36 | 38 |

| Shortness of breath | 35 | 37 |

| Headache | 22 | 23 |

| Chest pain | 15 | 16 |

| Diarrhea | 18 | 19 |

| Myalgia | 14 | 15 |

| Vomits/nausea | 14 | 15 |

| Pneumonia | 9 | 10 |

Seven of the patients underwent a respiratory virus panel test (namely Adenovirus, Influenza A and B and Respiratory Syncytial Virus) whose results were all negative.

The median length of symptomatic disease was 7 days, with a minimum of 2 and a maximum of 30 days. The median time between the onset of symptoms and performing SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR test was 3 days (IQR: 2–5.25).

The most common symptoms were cough (80%), rhinorrhea (72%) and fever (60%) (Table 1). An X-ray was performed in 35 patients, of which 23% (n=8) revealed a perihilar pattern, 31% (n=11) an interstitial pattern and 9% (n=3) a condensation pattern.

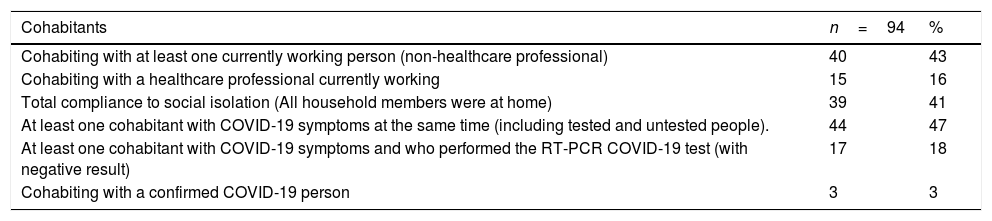

Of the 94 patients, 5 (5.3%) had history of a confirmed COVID-19 contact, being a cohabitant in three cases. A travel history to high-risk areas was absent in all patients.

Regarding household members, 55 children (59%) had at least one cohabitant currently working at the time, 15 (16%) of them were healthcare professionals (Table 2).

Household characterization of pediatric patients screened in the community of Amadora-Sintra, Portugal.

| Cohabitants | n=94 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Cohabiting with at least one currently working person (non-healthcare professional) | 40 | 43 |

| Cohabiting with a healthcare professional currently working | 15 | 16 |

| Total compliance to social isolation (All household members were at home) | 39 | 41 |

| At least one cohabitant with COVID-19 symptoms at the same time (including tested and untested people). | 44 | 47 |

| At least one cohabitant with COVID-19 symptoms and who performed the RT-PCR COVID-19 test (with negative result) | 17 | 18 |

| Cohabiting with a confirmed COVID-19 person | 3 | 3 |

There was only one positive test for SARS-CoV-2 in a five-year-old child, without epidemiologic linkage, with mild illness characterized by fever, odynophagia, myalgia and vomiting.

DiscussionAmong the 94 children tested in our emergency care between March 17 and April 2, only one was positive to SARS-CoV-2 (1%). In the same period, in our hospital 1668 adults were tested according to the same criteria and 145 (8.7%) had a positive test result. This means that, in the whole positive sample, children represented less than 0.7% of total COVID-19 cases attended in our emergency care.

In a study performed in the beginning of the pandemic in Spain, 63 children were tested for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR, 20% had history of contact with a confirmed COVID-19 case and the presence of the virus was confirmed in 5 patients (8%).9 Compared to the Spanish study, our study results revealed a lower percentage of direct contacts with infected people (5.3%) and only one positive case.

Our study data suggests a low incidence of the disease in the pediatric population. This can be explained by the containment efforts ordered by the Portuguese health care authorities, such as the closing of schools and kindergartens since March 15, which forced the confinement of at least one member of the family responsible for the minor. Despite this, in this study only 39 children (41%) had their entire family in social isolation.

Other explanation for the low proportion of children diagnosed with COVID-19 can be the sensitivity of the RT-PCR tests. There is no consensus as to the actual sensitivity, but many studies report that pharyngeal and nasal swabs sensitivity is around 63-71%.10,11 Therefore, there is a high number of false-negative results and the actual number of children with infection may be higher as many may go unnoticed due to a mild clinical presentation. Another factor that might have contributed to false negative results was the incorrect collection of specimens in children by health professionals without practice and the fact that children stay less quiet than adults during procedures. In adults, health professionals with expertise in otorhinolaryngology have been responsible for the performance of the tests but the same didn’t happen in the pediatrics department. There is a need for development of highly sensitive and specific tests and simultaneously to train health professionals how to correctly collect the swabs in order to minimize the false-negative results and ongoing transmission based on a false sense of security.

We can also hypothesize that the difference in the distribution, maturation and functioning of viral receptors is a possible reason of the age-related difference in incidence. The SARS-CoV-2 uses the angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) as the cell receptor in humans. By a buffering effect, and much like neutralizing antibodies, soluble ACE2 may help children to better counteract virus spreading to a cell target.12,13

The growing evidence, all over the world, is showing that children are less infected and have milder disease than adults.14 This difference seems to be related to the age as it is shown in a serological survey in which, according to the point-of-care test, seroprevalence was 1.1% in infants younger than 1 year, increasing with age until plateauing around 6% in people aged 45 years or older.15

We consider that the strict and restrictive indications to perform the RT-PCR-tests during the time of our study constitute a limitation because it may have led to many unidentified cases. Because this study took place at the beginning of the pandemic, we consider as another limitation the low number of infected people in Portugal at the time of our study.

In conclusion, as the pandemic progresses and more studies are published, there's evidence that the disease has a lower incidence in children compared to adults. Although the reasons for this are still unknown, children probably are less infected than adults. More studies are needed to improve knowledge about characteristics of COVID-19 in order to better understand the differences between children and adults and identify possible preventive strategies.

Conflict of interestNone.