Early diagnosis of HIV is still a challenge. Emergency Departments (EDs) suppose ideal settings for the early detection of HIV, since patients with high prevalence of hidden HIV infection are frequently attending those services. In 2020, the Spanish Society of Emergency and Emergency Medicine (SEMES) published a series of recommendations for the early diagnosis of patients with suspected HIV infection and their referral and follow-up in the EDs as part of its "Deja tu huella" program. However, the application of these recommendations has been very heterogeneous in our country. Considering this, the working group of the HIV hospital network led by the SEMES has motivated the drafting of a decalogue, with the aim of promoting the implementation and improvement of protocols for the early diagnosis of HIV in Spanish EDs.

El diagnóstico precoz del VIH es todavía un reto que requiere enfoques innovadores. Los servicios de urgencias (SU) son un escenario idóneo para la detección temprana del VIH, ya que reciben pacientes con conductas de riesgo y patologías asociadas con una alta prevalencia de infección oculta. En 2020, la Sociedad Española de Medicina de Urgencias y Emergencias (SEMES) publicó unas recomendaciones para el diagnóstico precoz de pacientes con sospecha de infección por VIH y su derivación y seguimiento en los SU enmarcadas dentro de su programa “Deja tu huella”. Sin embargo, se ha constatado que su implementación es muy heterogénea en nuestro país. En base a esto, el grupo de trabajo de la red de hospitales VIH liderado por la SEMES ha motivado la redacción de un decálogo con el objetivo de promover la implementación de los protocolos para el diagnóstico temprano del VIH en los SU españoles.

Despite the multiple measures that have been implemented in recent decades in an attempt to control the epidemic caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and the significant therapeutic advances achieved in this time, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is still a public health challenge associated with high global mortality.1 Today, global efforts are focused on curbing its transmission.2 However, late presentation of HIV infection (CD4+ T-cell count ≤350 cells/mm3 at the time of diagnosis) is considered one of the main drivers of its transmission,3 and continues to pose a challenge.

Late diagnosis of HIV infection is a problem for both those affected, as their risk of death increases, and for society, as the opportunity to interrupt the spread of the disease is missed because infected individuals are not aware of their situation and do not receive care.4 In Spain, it is estimated that 13% of those living with the virus do not know that they are infected,5 and one in two is diagnosed at a late stage in the infectious process.6 Both national and international guidelines recommend improving HIV testing practices and linking a person with an HIV diagnosis to healthcare services.7,8 In its guidelines and following indications from the World Health Organization, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) proposes increasing the coverage and acceptance of HIV diagnostic tests to achieve the United Nations epidemic control targets by 2030.8,9 These objectives aim to diagnose 95% of all HIV-positive individuals, provide at least 95% of those diagnosed with antiretroviral treatment and achieve viral suppression for at least 95% of those treated.8,9 For its part, in Spain, it is recommended that serology for HIV be carried out at different levels of healthcare for all those individuals who present with one of the indicator conditions associated with an undiagnosed HIV prevalence higher than 0.1% or who have an exposure risk.7

Emergency departments (ED) are an ideal setting for detecting cases of HIV that may go unnoticed at other levels of healthcare10 as they are the main point of contact with the health system for people with risk behaviours11,12 and young people without chronic diseases.13,14 Given the importance of early diagnosis and the opportunity for diagnosis that presents itself in the ED, in 2020, the Sociedad Española de Medicina de Urgencias y Emergencias [Spanish Society of Emergency Medicine] (SEMES) published a series of recommendations aimed at ED physicians to promote HIV screening in this setting, with the ultimate goal of minimising missed opportunities to diagnose the disease.15 This document was endorsed by the AIDS study group (Grupo de Estudio del sida, GeSIDA) of the Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica [Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology] (SEIMC). Along with this document, an initiative was implemented to promote early detection in EDs, the "Deja tu huella [Leave your mark]" programme, with the objective of increasing awareness and promoting the recommendations proposed in clinical practice.16 This programme is aligned with the UNAIDS17 objectives, and in its first 24 months to 31 December 2022, the project has managed to involve 103 hospitals, has performed more than 100,000 serologies and has made 871 new HIV diagnoses.16

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections and C (HCV) spread via risk behaviours shared with HIV. However, in order to initially kick-start the programme, the real-life protocol was designed specifically for HIV identification. This has made it possible to speed up its implementation by focusing on solving the technical problems associated with this type of protocol. Subsequently, the incorporation of screening for other sexually transmitted infectious diseases, such as hepatitis C and B, will be developed from 2023. In fact, several hospitals have already incorporated these into their ED screening protocols.

Although the HIV screening strategy in EDs has been shown to be efficient,18 a recent survey carried out on all Spanish public EDs that provide care for adults 24 h a day reveals that the monitoring and implementation of these recommendations is very heterogeneous across the country.19 Overall, only half of the Spanish centres that returned the questionnaire could request serology during urgent care, and only 18% got the results back the same day.19 This makes it difficult for healthcare personnel to find the motivation to carry out screening, increasing the risk of missed diagnostic opportunities.19 In addition, two-thirds of health professionals did not request serology in patients with signs and symptoms suggestive of infection, and approximately half did not think that EDs were the ideal place to perform diagnostic tests.19

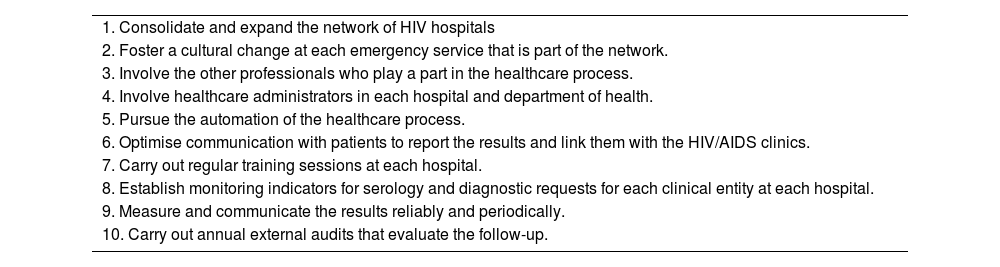

Given this situation, the HIV Hospital Network and its working group supported by SEMES have prompted the drafting of a decalogue (Table 1) to improve the implementation of recommendations for early diagnosis of HIV in Spanish EDs. This decalogue seeks to provide tools to educate the healthcare personnel involved and suggest resources to facilitate the diagnosis of HIV in all centres.

Decalogue to improve the implementation of the recommendations for early diagnosis of HIV in Spanish EDs.

| 1. Consolidate and expand the network of HIV hospitals |

| 2. Foster a cultural change at each emergency service that is part of the network. |

| 3. Involve the other professionals who play a part in the healthcare process. |

| 4. Involve healthcare administrators in each hospital and department of health. |

| 5. Pursue the automation of the healthcare process. |

| 6. Optimise communication with patients to report the results and link them with the HIV/AIDS clinics. |

| 7. Carry out regular training sessions at each hospital. |

| 8. Establish monitoring indicators for serology and diagnostic requests for each clinical entity at each hospital. |

| 9. Measure and communicate the results reliably and periodically. |

| 10. Carry out annual external audits that evaluate the follow-up. |

ED, emergency departments; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

The SEMES HIV Hospital Network has an organisation structured according to autonomous communities (AC) with a coordinator for each community. Each AC has at least three annual meetings. In addition, each of the coordinators represents their AC in the national group, which meets twice a year. The drafting process of the decalogue comprised three phases. In the first phase, the HIV network coordinators from each Spanish AC were asked via e-mail for a document outlining the 10 points they considered most important to motivate the implementation of the recommendations for the early diagnosis of HIV in EDs. These 10 points were to be drawn up at the local meetings held in each AC. In the second phase, a face-to-face meeting was held during which the representatives from the different ACs discussed the various decalogue suggestions and finally reached a consensus on the points to be included in the final decalogue. External advisors from the network of representatives of the SEISMIC and the GeSIDA group also participated proactively in this discussion. The third phase involved the drafting of the document with the result of this consensus. All authors reviewed the final document and approved its content.

DecalogueConsolidate and expand the network of HIV hospitalsThe HIV Hospital Network is currently made up of 103 Spanish centres that participate in the project for early detection of HIV in EDs as part of the SEMES "Deja tu huella" initiative.16 The existence of this expansive network of centres should be a resource for promoting the project generally, taking as an example hospitals that have overcome barriers that currently exist in other centres and learning from them.

In the future, we should also seek to expand this network to cover all Spanish hospital EDs, including private hospitals and primary care (PC). Specifically, implementing the screening programme in PC would be an opportunity to diagnose early-stage HIV infection. The extension of the programme to PC should start with training healthcare personnel, which specialists could carry out from centres where the programme has been successfully implemented. Likewise, computer system alerts or preconfigured reports should be considered, as has been proposed in the EDs, and whose implementation would be easier once their use has been established in the EDs.

Foster a cultural change at each emergency service that is part of the networkPlacing value on the role of the ED as a key setting for the diagnosis of HIV and to identify uninfected people at risk is a priority. EDs are one of the pillars in the fight against pandemics, since patients are attended to who would have missed diagnostic opportunities had they not been seen there. Detecting these cases and linking them to healthcare means patients have a better clinical prognosis. A cultural change in EDs, which involves a change in professional attitude and practice, aims to establish good adherence to the screening protocol, the healthcare process and the recommendations for EDs regarding the early diagnosis of patients with suspected infection by HIV and their referral for study and follow-up. Individuals at high risk of acquiring HIV infection, such as men who have sex with men and transgender women who are seen for the use of post-exposure prophylaxis or STIs, should be advised about evaluation at PreP dispensing units and referred to those centres known as the AIDS and STIs information and prevention centres. Led by emergency medicine professionals, everyone involved in the process, including nursing professionals, must participate in this change in mentality. Emergency medicine specialty approval would foster the implementation of this and other programmes by standardising the training of emergency medicine physicians and ensuring homogeneity in care.

Involve the other professionals who play a part in the healthcare processThe proper functioning of any healthcare process depends on the multidisciplinary collaboration of all potentially involved, both from the emergency department (nursing) and other specialties (infectious diseases or clinical microbiology). Mutual coordination and shared leadership are fundamental for the success of the established protocol. At least one annual meeting with microbiology and HIV specialists should be held to evaluate the process. These multidisciplinary meetings could be scheduled within the framework offered by the conferences of each specialty involved.

Involve healthcare administrators in each hospital and department of healthA healthcare improvement programme that requires a change in a professional culture, ongoing training and changes in technological resources, among other processes, needs to involve all system agents. The involvement of healthcare administrators is essential to support the implementation of the process and its continuous improvement since initiating the programme requires institutional approval by hospital management or medical directorates. Additionally, it would be highly recommended to integrate the programme into each hospital's objectives or quality indicators to encourage adherence. Protocols must be generated to improve the healthcare process for the diagnosis of HIV. To gain support for them, it will be necessary to measure the impact of the actions of emergency medicine professionals about HIV screening, both financially and in terms of public health.

Pursue the automation of the healthcare processThe high demand for healthcare and the high staff turnover in EDs makes it necessary to establish mechanisms that guarantee adherence to the protocol and the sustainability of the HIV screening project in the different EDs. Automating requests for serology through alerts or preconfigured reports in the computer system is one of the keys to success in this effort for the early detection of HIV. Establishing a plan and implementing decision-support processes in each hospital is considered an essential requirement. This point implies the collaboration of the local and regional administration. This automation does not mean an automatic request for serology without the physician's intervention, but instead, a computer aid that identifies certain patients and alerts them to this possibility, facilitating a request by the attending physician, who should ultimately verify the need for the test. These decision-making algorithms must be designed considering the patients' demographic data, their personal history, the reason for the consultation, the complementary tests or treatments prescribed by the doctor or the diagnosis established during the care in the ED. Establishing collaboration with IT departments and strengthening these institutionally and with policies is essential.

Optimise communication with patients to report the results and link them with the HIV/AIDS clinicsIt is important to establish a clear circuit for communicating the results of the test to patients, in addition to facilitating rapid access to HIV infection monographic consultations. In this way, antiretroviral treatment can be started early, avoiding the spread of the virus and secondary infections. This circuit must be, for each participating centre, clear, specific and agreed upon by all the professionals who may be involved in the process, adapting to capacity and available resources. This is also crucial to avoid possible legal issues for the health professionals involved. Efforts should be made to ensure a period of fewer than seven days between a positive serology result and the assessment of the patient at the HIV outpatient clinic. In the event of a negative result, it would be advisable to implement follow-up strategies to perform control serologies in window periods (at 30–45 days, and subsequently when necessary) in cases where the risk exposure was very close to the time of screening.

Carry out regular training sessions at each hospitalAll personnel involved in the processes of detection of HIV infection, referral and follow-up of patients must receive continuous training. This includes emergency medicine physicians, specialists, residents, nursing staff, microbiologists, biochemists, hospital pharmacists, infectious diseases specialists and internists and, in general, all personnel who may be involved. The training sessions should make clear the motivation for the “Deja tu huella” project and the protocol for early detection of HIV to raise awareness among staff and motivate the participation of those who have not yet joined the initiative. The training should be carried out both at the local level (hospital and AC) and at the national level through the SEMES. Likewise, taking into account the high staff turnover of EDs, training sessions should be periodic. Finally, a training schedule should be implemented based on the characteristics of the centre and, especially, the turnover rate of physicians in the ED.

Establish monitoring indicators for serology and diagnostic requests for each clinical entity at each hospitalIt is important to establish monitoring indicators, which enable monitoring of the healthcare process and progressively improve it. The definition of these indicators will mean all the centres involved advance in a standardised way. The established indicators are the following: (1) Rate of adherence to the SEMES recommendations; that is, the percentage in which serology is requested due to the reasons for consultation established in the recommendations; (2) Monitoring of the results; that is, the time elapsed from when the serology is performed to the communication of the result to the patient and the appointment in specialised HIV/AIDS clinics, and (3) Existence of monthly monitoring meetings with microbiologists and HIV specialists.

In addition, establishing strategies that facilitate compliance with the recommendations should be promoted, such as specific microbiological profiles that include HIV serology in certain clinical cases or the development of automated alerts that facilitate the work of the attending doctor. These alerts should be shared with the PC physicians assigned to these patients to avoid the risk of loss of information when making joint decisions.

Measure and communicate the results reliably and periodicallyThe evaluation and analysis of the results obtained are linked to a periodic review of the process and a continuous effort to improve. The protocol is a dynamic entity that must be adapted based on evidence obtained over time.

Giving feedback to the team participating in the project on the results boosts motivation and improves adherence to the protocol. Reporting the results is an incentive for the continuity and improvement of the process. It is, therefore essential that the results of the process (number of patients recruited, positive results obtained…) are measured systematically at the participating centres. Including this in the healthcare, objectives can support the implementation of these protocols.

The results should be disseminated at the local level and other centres to recruit new clinicians to adhere to the protocol and at the societal level to publicise the project's scope and raise awareness in the population about requesting serology in case of suspected HIV. In this sense, it is crucial to involve patient associations, collectives and citizen movements, so they are properly informed about the programme and can participate in its dissemination.

Carry out annual external audits that evaluate the follow-upExternal evaluations and audits in terms of quality will make it possible for the proper functioning of the screening process and the follow-up of people with HIV in the centres involved to be recognised, serving as an example for others. In addition, it will be a great motivation for accredited EDs. Public funds and the involvement of scientific societies, such as SEMES or SEIMC, will be necessary for these audits. For those centres that also incorporate HBV, HCV or syphilis screening, the audits could cover the evaluation of these programmes as a whole.

FundingThe SEMES HIV Hospital Network receives unearmarked funding from Laboratorios Gilead Science SLU.

Conflicts of interestJGC has received funding for educational or research activities from Gilead, GSK, MSD, Pfizer, Angellini and Thermofisher. MJPE has received funding for conference attendance, educational or advisory activities, and grants from pharmaceutical companies Gilead, Janssen, Abbvie, MSD and ViiV. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

To Vanessa Marfil, from Medical Statistics Consulting (MSC), for her help drafting this manuscript.