Sexually transmitted diseases such as cervicitis, proctitis and urethritis are associated with high rates of HIV infection. When these pathologies are suspected, HIV serology should be requested.

Material and methodsA retrospective study was performed during 2018 at the Hospital Costa del Sol (Marbella, Málaga, Spain). HIV serologies requested in patients who were asked for PCR for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae were reviewed.

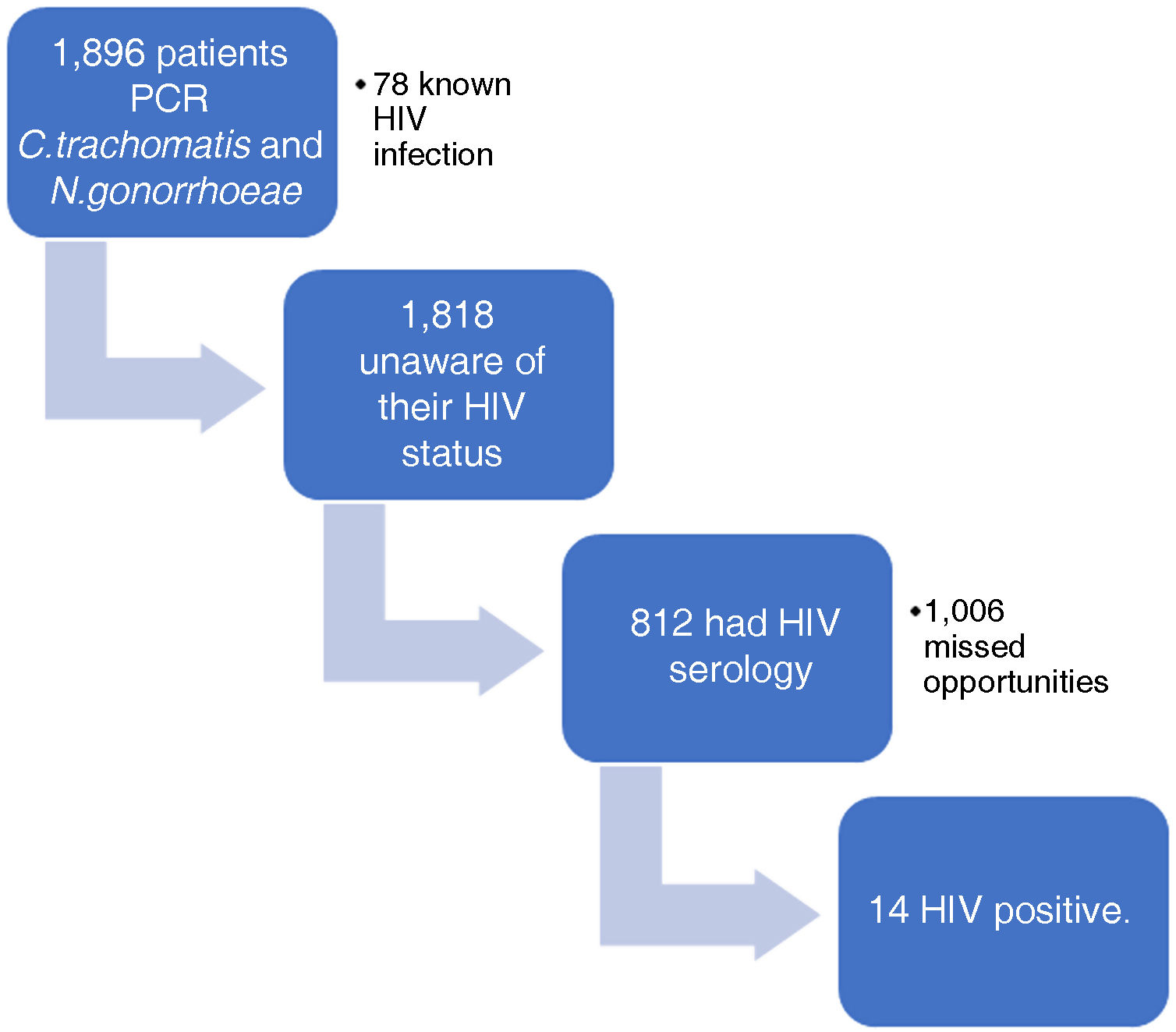

ResultsA total of 1818 patients were evaluated, in which HIV serology was performed in 44.7%, of which 14 (1.7%) were positive. The remaining 55.3% were missed diagnostic opportunities.

ConclusionsC. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae infections are associated with a high rate of occult HIV infection. The degree of suspicion of HIV in this population remains low and it is essential that it be reinforced in the presence of the possibility of infection by these pathologies.

Las enfermedades de transmisión sexual, como la cervicitis, la proctitis y la uretritis, se asocian a altas tasas de infección por VIH. Ante la sospecha de estas patologías, se debería solicitar una serología del VIH.

Material y métodosEstudio retrospectivo realizado durante 2018 en el Hospital Costa del Sol (Marbella, Málaga). Se revisaron las serologías para el VIH solicitadas en pacientes a los que se les pidió una PCR para Chlamydia trachomatis y Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

ResultadosSe valoraron 1.818 pacientes, en los que se realizó serología para el VIH al 44,7%, de las cuales 14 (1,7%) resultaron positivas. El 55,3% restante fueron oportunidades perdidas de diagnóstico.

ConclusionesLas infecciones por C. trachomatis y N. gonorrhoeae están asociadas a una elevada tasa de infección oculta por el VIH. El grado de sospecha de VIH en esta población sigue siendo bajo, y resulta esencial que se refuerce ante la posibilidad de infección por estas patologías.

Reducing late diagnosis of HIV infection is one of the main challenges to ending acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).1 The established definition of diagnostic delay refers to people with a CD4 cell count below 350 cells/μl at diagnosis, or who have an AIDS-defining event, regardless of CD4 cell count.2 Early diagnosis of HIV infection has clear benefits for the individual and the community by reducing both morbidity and mortality rates among those affected, as well as by changing behaviours that promote transmission.3

In Spain there are an estimated 150,000 people living with HIV infection, an overall prevalence in the Spanish adult population of four per 1000.4,5 The available data suggest that 7.5% of them are unaware of their status.5 Moreover, 45.9% of people diagnosed for the first time in 2019 showed signs of late diagnosis.6 Early detection is possible, partly because HIV testing here in Spain is free and confidential for all.

As a result of the European HIDES-27 project, a guide for HIV testing based on HIV-indicative conditions was developed in Spain in 2013, and in 2014 the Spanish National AIDS Plan published the Recommendation Guidelines for the early diagnosis of HIV in the healthcare setting.8 It lists a number of HIV indicator diseases associated with an undiagnosed HIV prevalence >0.1% and other diseases possibly associated with an undiagnosed HIV prevalence >0.1%. The guidelines recommend HIV testing for these patients, in addition to those with AIDS-defining illnesses.8

November 2012 saw publication of the Spanish National AIDS Plan Secretariat/SEMES [Spanish Society of Emergency Medicine]/GESIDA [AIDS Study Group] Consensus Document on Emergencies and HIV,9 which lists a number of situations in which the prevalence of HIV infection may be higher than 1% and a diagnostic test for HIV-1 infection may be advisable, unless there are other reasons to explain the diagnosis (apart from those defining AIDS). Both documents include some sexually transmitted infections (STI), such as syphilis, urethritis and infection with viruses such as herpes simplex, as indicators of HIV infection.8,9

If any of these conditions are suspected clinically, HIV testing should be requested. This study evaluates the degree of clinical compliance with these recommendations in real-life situations in a second-level hospital over the period of a year. The main objective was to analyse requests for HIV serology in patients with suspected STI and estimate the number of missed opportunities for diagnosis (MOD) for early diagnosis of HIV.

Material and methodsRetrospective cross-sectional descriptive study under real-life conditions. We analysed all patients treated in the health area of the Costa del Sol hospital in Marbella in 2018 whose doctor requested a PCR for Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Trichomonas vaginalis. Patients with known HIV infection were excluded. Of the remaining patients, we studied how many had been tested for HIV serology at the same time. Of the serologies performed (Atellica® IM EHIV reagent Kit, Siemens), we analysed the number of positive results and whether or not they were subsequently confirmed by Line Immunoassay (LIA) (INNO-LIA HIV I/II Score, Fujirebio) (Fig. 1).

Descriptive analysis was performed by presenting frequencies and percentages of qualitative study variables (sample origin, pathogen identification, HIV serology yes/no, HIV positive/negative serology) using SPSS 23.0.

ResultsA total of 2258 requests for PCR tests for C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae had been made for 1896 patients. Of these samples, 139 (6.16%) were from anal swabs, 1327 (58.77%) cervical, 16 (0.71%) ear/nose/throat and 776 (34.36%) urethral;

5.27% of the samples did not arrive properly at the laboratory, due to problems with the sampling conditions, the medium or loss in transit. Of the 2141 samples processed, 85.84% were pathogen-free, 12.2% were pathogenic, and 42 (1.96%) undetermined. In 169 (7.89%) samples C. trachomatis was detected, 68 (3.18%) samples were positive for N. gonorrhoeae and in 22 cases (1.03%) T. vaginalis was detected.

Of the 1896 patients, 78 had known HIV infection. Of the remaining 1818, HIV serology was performed on 44.66%, while the rest were MOD. Among the 812 serologies performed, 1.48% were positive for HIV, all of which were confirmed by Line Immunoassay (LIA). Of the positive serologies, the mean CD4 level was 566.76 cells per microlitre, with only two patients in the late diagnosis range (<350 CD4 cells per microlitre): 257.41 and 235.33 cells per microlitre respectively.

DiscussionAt our centre, 12.1% of the samples tested for suspected C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoeae disease were positive. The prevalence of hidden HIV infection in these patients was 1.72%. However, only 44.66% of patients were tested for HIV serology, with 55.33% of cases being MOD.

The high rate of hidden HIV infection in patients with suspected STI is well known. Studies show the prevalence to be between 0.8% and 3%.10 The high rate of association has several possible explanations. One of the most common symptoms shared by C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae infection and other STI (syphilis, human papillomavirus infection, Trichomonas or herpes) is the development of ulcers or skin lesions which can cause inflammation of the affected area, whether rectal, vaginal or oral.11 This mechanism has an influence in two ways. On the one hand, it increases the risk of HIV infection in people who are not infected with HIV, but who have mucosal inflammation, due to the increase in lymphocytes (including CD4) in the affected area.12 While, on the other, people living with HIV who also have an STI are at increased risk of transmitting HIV through the sexual route, as increased lymphocytes in the genital tract are also associated with increased viral shedding by these routes.13 In fact, some studies estimate that 10% of new diagnoses of HIV infection among men who have sex with men are caused by an existing gonorrhoea or Chlamydia infection.14 In studies in epidemiological areas close to ours, 27.5% of their new HIV diagnoses had an STI at the time of diagnosis.15

In our study, in line with other observational studies, the number of MOD is high. Gargallo-Bernad et al.4 found that 16% of the new HIV diagnoses studied had previously consulted for an STI and these were on the list of indicator conditions which generated the most MOD in the late diagnosis population; 44% of their late diagnoses had previously consulted for an STI.

This study has a series of limitations. Due to a lack of availability of data, we did not analyse the risk factors associated with a greater suspicion of hidden HIV infection by the clinician which led them to order testing or not. As this is a single-centre study, the results cannot be directly extrapolated to other centres or regions. Moreover, all the samples taken were exploited with a high statistical power, thanks to the exhaustiveness of the recording carried out.

The high prevalence of hidden HIV infection in people with these conditions, and the high degree of suspicion, will enable us to set a target for reinforcing early diagnosis strategies which will help us reduce the number of people with hidden infection. In our opinion, measures are needed to increase the level of suspicion of hidden HIV infection in people with these conditions. These measures should start with teaching and training in early detection of HIV infection, through missed opportunity markers and alert criteria, training courses, awareness campaigns and interdisciplinary clinical sessions.

FundingGilead Sciences, S.L.U. contributed to the funding of this publication. This company had no involvement in the contents of this publication or the selection of authors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.