We have read with a great interest the valuable editorial by Dr Ballesté-Delapierre and Dr Vila-Estapé1 in which they ask about the detection of Salmonella foodborne outbreaks (FO) in Spain.

In Spain for the period 2012–2014, el Centro Nacional de Epidemiologia2 reports that 702 FO of Salmonella were notified and S. Typhimurium (ST) was the etiologic agents in less than 20% of these outbreaks. By microbiologic culture, there were 4329 reported cases of ST and 135 cases of Monophasic S. Typhimurium (MST). However, the most frequent agent (over 50%) of FO was S. Enteritidis (SE), and a total of 3656 reported cases of SE. In addition, very few studies of FO caused by ST or MST have been published in Spain in the last 10 years,3–5 despite the fact that the first description of epidemic MST associated with pork products was made in Spain by Echeita and co-authors in 1997.6

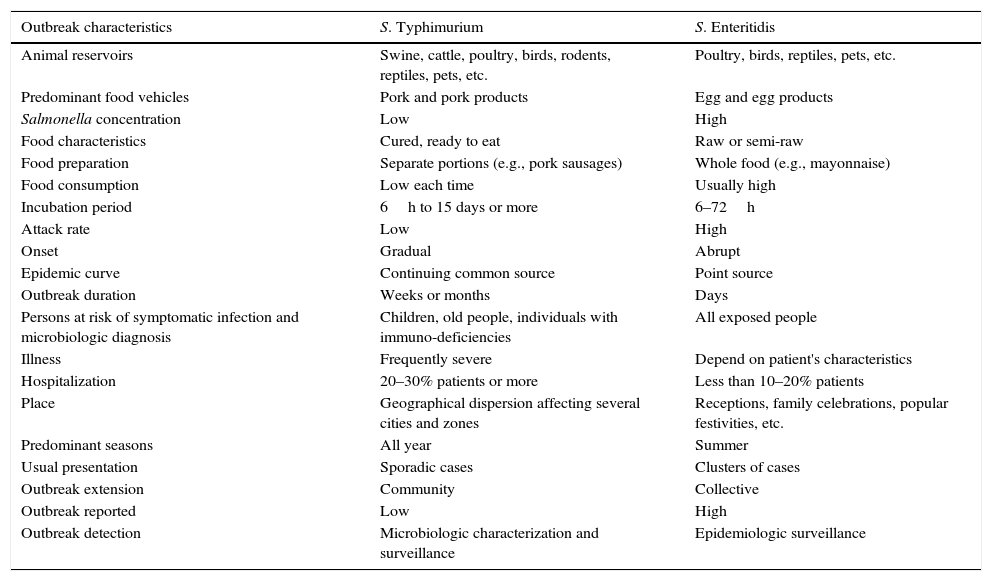

However, FO caused by ST in Spain probably are more frequent than the official figures reflect. We put forward some epidemiologic arguments that could explain why these outbreaks are more difficult to detect than FO caused by SE (Table 1):

- -

The food vehicle for FO caused by SE, the principal reservoir being poultry, is frequently eggs and egg products, which are consumed raw or semi-raw in high quantities and which could have high concentrations of Salmonella. The ST food vehicle is more variated in its animal reservoirs, which include cattle, chicken, rodents, and swine; the high prevalence of ST and MST in the Spanish pig farms has been highlighted.7 Concentrations of ST depend on how the food vehicle has been processed. In the case of pork derivatives, some products are cured and ready to eat, consumption may be low each occasion and ST concentrations are like to be small. In addition, dried pork sausage and chorizo were the food vehicle in the two mentioned FO.4,5

- -

Dependent on exposure, the FO caused by SE may affect a high number of people, and may have a point source epidemic curve. Exposed people of all ages can be infected with symptoms and the severity depends on patient's characteristics. The attack rate is high although the hospitalization rate is usually low. Receptions, family celebrations, and popular festivities are places where these FO originate; they have a short duration and an incubation period of 6–72h. Presentation, frequently takes the form of clusters of cases. These FO could detect by the epidemiologic surveillance before Salmonella microbiological characterization.

- -

In general, FO caused by ST may be of prolonged duration and the epidemic curve could be a continuing common source. The attack rate may be low and the people affected are children, old people, and adults with immuno-deficiencies; the illness is frequently severe with a high hospitalization rate. Because of the low concentrations of ST in the products, infection in healthy adults could be asymptomatic or involve only mild symptoms. The incubation period is longer and can be up 16 days or more. Presentation usually takes form of sporadic cases.8 However, ST or MST can produce point source FO when the agent's concentration in the food vehicle is high and more than one Salmonella serotype may be associated with the same FO. Detecting these FO requires the microbiological characterization of the Salmonella strains, including serotypes, phage types, and more advanced molecular methods such as pulsed field electrophoresis, multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis, and whole-genome sequencing.

Some differential characteristics of foodborne outbreaks of S. Typhimurium and S. Enteritidis.

| Outbreak characteristics | S. Typhimurium | S. Enteritidis |

|---|---|---|

| Animal reservoirs | Swine, cattle, poultry, birds, rodents, reptiles, pets, etc. | Poultry, birds, reptiles, pets, etc. |

| Predominant food vehicles | Pork and pork products | Egg and egg products |

| Salmonella concentration | Low | High |

| Food characteristics | Cured, ready to eat | Raw or semi-raw |

| Food preparation | Separate portions (e.g., pork sausages) | Whole food (e.g., mayonnaise) |

| Food consumption | Low each time | Usually high |

| Incubation period | 6h to 15 days or more | 6–72h |

| Attack rate | Low | High |

| Onset | Gradual | Abrupt |

| Epidemic curve | Continuing common source | Point source |

| Outbreak duration | Weeks or months | Days |

| Persons at risk of symptomatic infection and microbiologic diagnosis | Children, old people, individuals with immuno-deficiencies | All exposed people |

| Illness | Frequently severe | Depend on patient's characteristics |

| Hospitalization | 20–30% patients or more | Less than 10–20% patients |

| Place | Geographical dispersion affecting several cities and zones | Receptions, family celebrations, popular festivities, etc. |

| Predominant seasons | All year | Summer |

| Usual presentation | Sporadic cases | Clusters of cases |

| Outbreak extension | Community | Collective |

| Outbreak reported | Low | High |

| Outbreak detection | Microbiologic characterization and surveillance | Epidemiologic surveillance |

Following studies in the United States (U.S.), one Salmonella isolate case in a culture may represent 38.6 cases in the community.9 In the period 2012–2014, Spain reported an annual mean of 5600 cases of Salmonella2 and following this estimation more than 200,000 cases could have occurred; indeed Spain is already the European country with the second highest rates of Salmonella infections.10 When we consider that most Salmonella infections are transmitted by foods, the implementation of a specific surveillance by a foodborne diseases network such as those in the U.S. and other countries could usefully to increase detection, control, and prevention of Salmonella and other etiologic agents of FO.9