Limited data is available regarding the hepatic safety of maraviroc in patients co-infected with HIV and HCV and/or HBV. Our objective was to compare the hepatic safety profile and fibrosis progression in HIV-mono-infected patients and co-infected with HCV and/or HBV treated with maraviroc.

MethodsRetrospective multicentre cohort study of HIV-infected patients receiving treatment with a maraviroc-containing regimen in 27 hospitals in Spain.

ResultsA total of 667 patients were analyzed, of whom 313 were co-infected with HCV (n=282), HBV (n=14), or both (n=17). Maraviroc main indications were salvage therapy (52%) and drug toxicity (20%). Grade 3•4 hypertransaminasaemia (AST/ALT >5 times ULN) per 100 patient-years of maraviroc exposure, was 5.84 (95% CI, 4.04•8.16) and 1.23 (95% CI, 0.56•2.33) in co-infected and HIV-mono-infected patients, respectively (incidence rate ratio, 4.77; 95% CI, 2.35•10.5). However, the degree of aminotransferase abnormalities remained stable throughout the study in both groups, and no significant between-group differences were seen in the cumulative proportion of patients showing an increase in AST/ALT levels greater than 3.5 times baseline levels. No between-group differences were seen in liver fibrosis over time. With a maraviroc median exposure of 20 months (IQR, 12•41), two patients (0.3%) discontinued maraviroc because of grade 4 hepatitis, and other 2 died due to complications associated to end-stage-liver disease.

ConclusionsMaraviroc-containing regimens showed a low incidence of hepatitis in a large Spanish cohort of HIV-infected patients, including more than 300 patients co-infected with HCV and/or HBV. Co-infection did not influence the maximum liver enzyme level or the fibrosis progression throughout the study.

La seguridad hepática del maraviroc en pacientes coinfectados por VIH y VHC y/o VHB es poco conocida. Nuestro objetivo es comparar el riesgo de hepatitis y la progresión de la fibrosis hepática en pacientes monoinfectados por VIH y coinfectados por VHC y/o VHB, tratados con maraviroc.

Mèc)todosEstudio de cohortes, retrospectivo, en pacientes infectados por VIH, tratados con maraviroc en 27 hospitales españoles.

ResultadosAnalizamos 667 pacientes, 313 coinfectados por VHC (n=282), VHB (n=14) o ambos (n=17). El rescate (52%), y la toxicidad farmacológica (20%) fueron las principales indicaciones de tratamiento con maraviroc. La incidencia de hipertransaminasemia de grado 3•4 (AST o ALT >5 veces el LSN), por 100 paciente-años de exposición a maraviroc, fue 5,84 (IC 95%, 4,04•8,16) y 1,23 (IC 95%, 0,56•2,33) en coinfectados y monoinfectados por VIH, respectivamente (razón de tasas, 4,77; IC95%, 2,35•10,5). No se observaron diferencias en la proporción acumulada de pacientes con elevación de AST o ALT mayor de 3,5 veces respecto al valor basal, ni en la progresión de la fibrosis hepática entre ambos grupos. Tras una mediana de tratamiento de 20 meses (AIC, 12•41), dos pacientes (0,3%) discontinuaron el maraviroc por hepatitis de grado 4, y dos pacientes fallecieron por enfermedad hepática.

ConclusionesEn una cohorte española de pacientes infectados por VIH que incluye más de 300 pacientes coinfectados por VHC y/o VHB, maraviroc mostró una baja incidencia de hepatitis. La coinfección no afectó al grado de elevación de las transaminasas ni a la progresión de la fibrosis hepática.

Approximately 1•8% of HIV-infected patients develop severe hepatitis, mostly grade 3 or 4 elevations in aminotransferases, during the first year of antiretroviral therapy (ART).1 Coinfection with either hepatitis B (HBV) or hepatitis C (HCV) has been frequently reported as a major risk factor for liver toxicity after initiation of ART.1

Although the incidence of severe liver toxicity is lower with currently recommended regimens, and the majority of cases involve asymptomatic liver enzyme elevations2•5 some cases of severe liver disease have been still reported3 and ART-related hepatotoxicity is a concern in the management of HIV-infected subjects, mainly in those coinfected with HCV and/or HBV.

Initial concerns were raised in regard with the hepatic safety of CCR5 antagonists, following the description of severe cases of hepatotoxicity with aplaviroc.6 Maraviroc (MRV), the first and only CCR5 antagonist approved so far for ART, has shown a favorable safety profile both in patients enrolled in clinical trials and in the expanded access program.7 However, very limited data is available regarding the hepatic safety of maraviroc in patients co-infected with HCV and/or HBV,8 and the package insert for maraviroc includes some specific warnings in regard with the potential risk of hepatotoxicity.9

On the other hand, development of progressive liver disease is one of the principal comorbidities in HIV infected patients coinfected with HCV and/or HBV, and complications associated to end-stage liver disease remain a major cause of morbidity and mortality among coinfected patients.10 In chronic hepatitis, the CCR5/RANTES pathway appears to be involved in the inflammatory response, a critical step in the promotion of hepatic fibrosis, metabolic liver disease and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma.11

Preclinical data, obtained from different animal models of liver injury, have shown that blocking the CCR5 activation pathway could play a protective role on liver fibrosis progression12,13 hepatocellular carcinoma development,14,15 and in protecting against the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).16

The primary outcome of this substudy was to compare the liver safety profile of maraviroc-containing ART in a large heterogeneous cohort of patients coinfected or not with HBV and/or HCV, in real-life conditions. As a secondary outcome we studied the impact of maraviroc treatment on liver fibrosis progression by analyzing changes in FIB-4 index over time.

MethodsStudy design and follow-upDemographic and clinical data from all maraviroc-treated subjects in 27 centers across Spain were retrospectively collected in an observational multicenter cohort study. Complete study design and data on efficacy and overall safety have been reported elsewhere.17 Briefly, all HIV-1 infected adults receiving a first dose of maraviroc and with at least one follow-up visit were recruited. Data obtained from every 3•6 months scheduled visits until the last follow-up control were entered into a web database, from October 2012 to May 2013 at each center, and transferred to a central database for data monitoring and analysis. Follow-up data included clinical adverse events, laboratory parameters, progression of HIV disease (occurrence of an AIDS-defining event or death), discontinuation of maraviroc and reasons for discontinuing maraviroc.

HBV infection was defined as testing positive for hepatitis B surface antigen and HCV infection as testing positive for HCV antibodies.

StatisticsAdverse events were graded in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Division of AIDS scale.18 Elevations in AST and ALT, were graded as grade 1 (AST or ALT 1.25•2.5í the upper limit of normality, ULN); grade 2 (AST or ALT 2.6•5í ULN); grade 3 (AST or ALT 5.1•10í ULN); grade 4 (AST or ALT >10í ULN). As almost half of patients were coinfected with HCV/HBV and amongst them, 50% had elevated AST/ALT levels at baseline, we performed a sensitivity analysis defining grade 3•4 hypertransaminasemia as the increase of liver enzymes more than 3.5 times over baseline values.

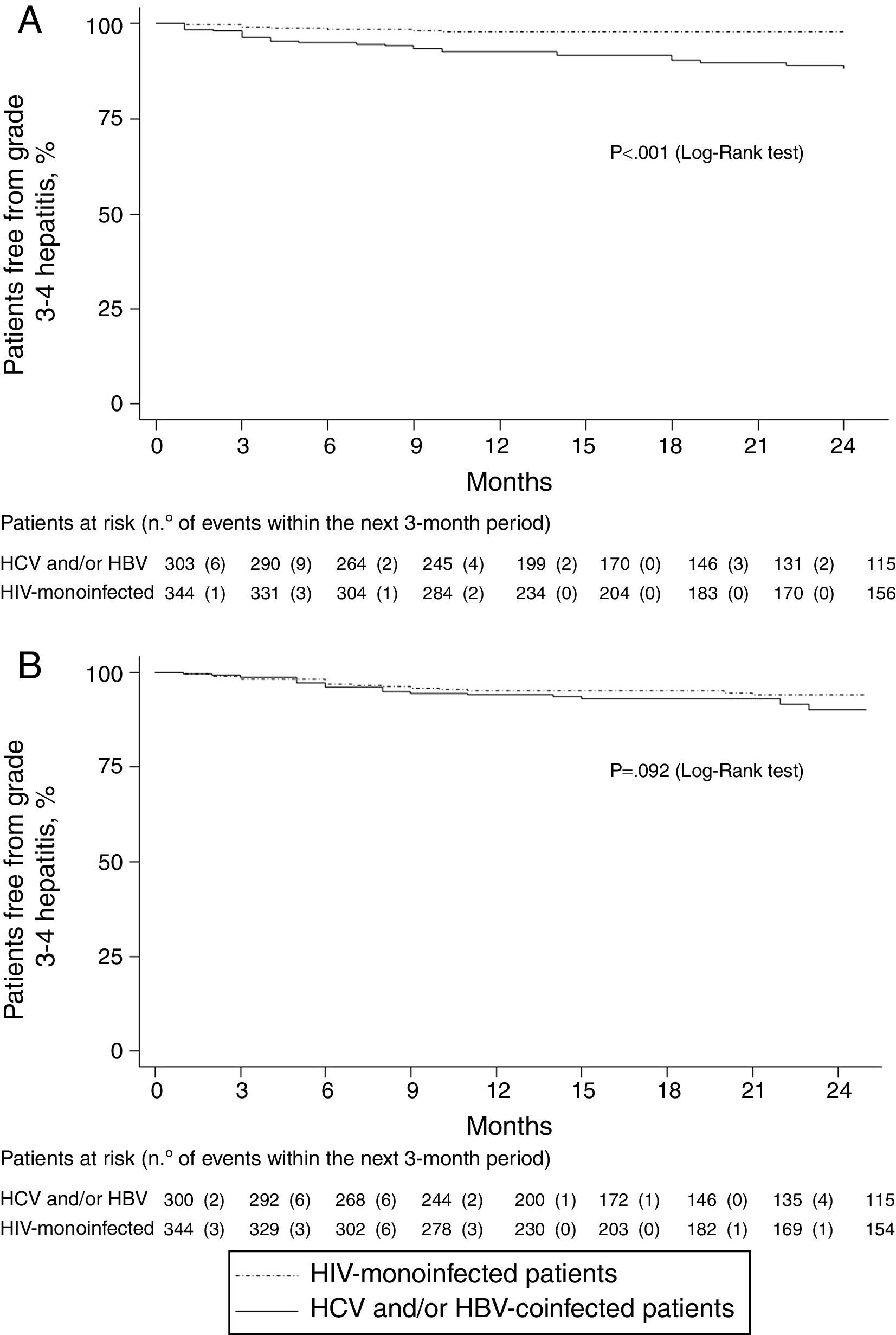

The proportion of patients with grade 3•4 hypertransaminasemia was calculated as the number of events divided by the number of patients exposed to MRV in each group, and the incidence rate as the number of events divided by years of exposure to maravirocí100. Incidence rates in HCV/HBV co-infected and HIV mono-infected patients were compared using the incidence rate ratio and its corresponding 95% CI. The survival probability of being free of grade ≥3 hypertransaminasemia was estimated by Kaplan•Meier method, and we used the log-rank test for comparison of hepatitis free survival curves of HIV-monoinfected and coinfected patients.

Cox proportional hazards models (univariate and multivariate) were fitted to investigate those factors associated with grade ≥3 hypertransaminasemia, including gender, age, HCV and/or HVB coinfection, CD4+ lymphocytes; detectable plasma HIV RNA; maraviroc dose, time of maraviroc exposure and liver fibrosis at baseline as covariates.

Both in HIV-monoinfected and coinfected patients included in the study, liver fibrosis was estimated by FIB-4 index, calculated as: ageíAST/platelet count (í109/L)í(ALT)1/2.19 FIB-4 index trend along the study period was evaluated using a generalized linear mixed effect model: FIB-4 index as the outcome variable (using data from baseline, months 6, 12, 16 and 24) and time of follow up in years as a main covariate.

All tests were two-sided and p values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Categorical variables are expressed as number (percentage) and continuous variables as median (interquantile range, IQR).

The Wilcoxon's rank-sum test was used for comparisons between two continuous variables, and Chi-squared tests to compare two categorical variables. For statistical analysis we used SPSS software package (version 20, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards and the Ethic Committees at all investigative centers. All data remained anonymous.

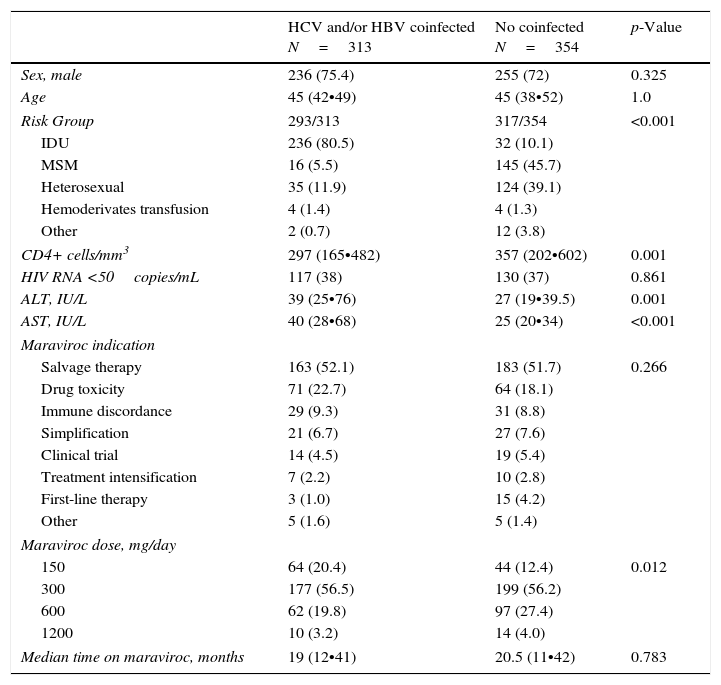

ResultsPatient characteristicsBaseline characteristics of 667 patients analyzed are summarized in Table 1. Of them, 313 (46.9%) were co-infected either with HCV (n=282; 42.2%) or HBV (n=14; 2.1%) or both HBV and HCV (n=17; 2.5%). Median age was 45 years; 74% were men; main route of infection was IDU (80.5%) in coinfected and sexual intercourse (84.8%) in HIV-monoinfected patients. Salvage therapy was the indication for the maraviroc-containing regimen in more than half of patients in both groups. Maraviroc dose ranged from 150mg once daily to 600mg/twice daily, without differences between groups (Table 1).

Demographic and clinical baseline characteristics.

| HCV and/or HBV coinfected N=313 | No coinfected N=354 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, male | 236 (75.4) | 255 (72) | 0.325 |

| Age | 45 (42•49) | 45 (38•52) | 1.0 |

| Risk Group | 293/313 | 317/354 | <0.001 |

| IDU | 236 (80.5) | 32 (10.1) | |

| MSM | 16 (5.5) | 145 (45.7) | |

| Heterosexual | 35 (11.9) | 124 (39.1) | |

| Hemoderivates transfusion | 4 (1.4) | 4 (1.3) | |

| Other | 2 (0.7) | 12 (3.8) | |

| CD4+ cells/mm3 | 297 (165•482) | 357 (202•602) | 0.001 |

| HIV RNA <50copies/mL | 117 (38) | 130 (37) | 0.861 |

| ALT, IU/L | 39 (25•76) | 27 (19•39.5) | 0.001 |

| AST, IU/L | 40 (28•68) | 25 (20•34) | <0.001 |

| Maraviroc indication | |||

| Salvage therapy | 163 (52.1) | 183 (51.7) | 0.266 |

| Drug toxicity | 71 (22.7) | 64 (18.1) | |

| Immune discordance | 29 (9.3) | 31 (8.8) | |

| Simplification | 21 (6.7) | 27 (7.6) | |

| Clinical trial | 14 (4.5) | 19 (5.4) | |

| Treatment intensification | 7 (2.2) | 10 (2.8) | |

| First-line therapy | 3 (1.0) | 15 (4.2) | |

| Other | 5 (1.6) | 5 (1.4) | |

| Maraviroc dose, mg/day | |||

| 150 | 64 (20.4) | 44 (12.4) | 0.012 |

| 300 | 177 (56.5) | 199 (56.2) | |

| 600 | 62 (19.8) | 97 (27.4) | |

| 1200 | 10 (3.2) | 14 (4.0) | |

| Median time on maraviroc, months | 19 (12•41) | 20.5 (11•42) | 0.783 |

Results are expressed as number (%) or median (interquantile range). IDU, injection drug users; MSM, men who have sex with men.

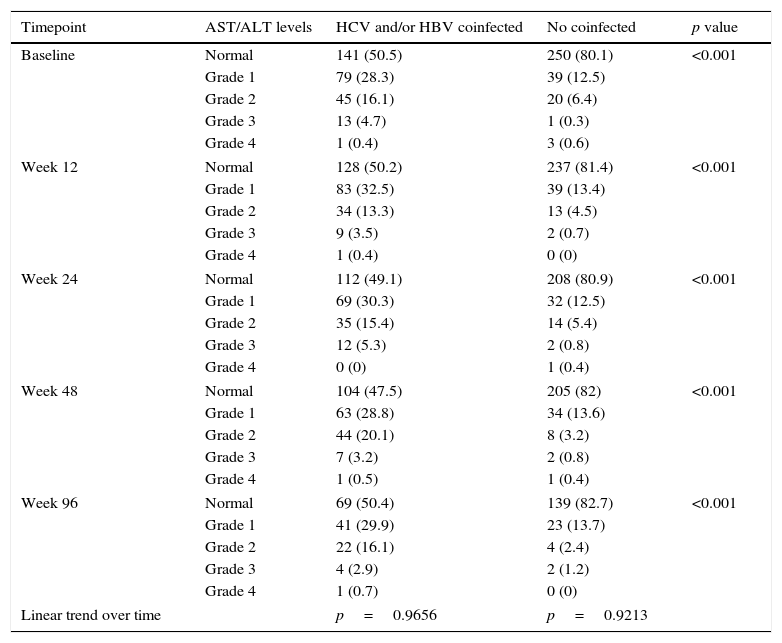

At baseline, aminotransferase levels were higher in coinfected vs. monoinfected patients, and 50% of coinfected vs. 20% of HIV-monoinfected patients had abnormal ASL/ALT levels (Table 2). The proportion of patients showing aminotransferase elevations and the degree of aminotransferase abnormalities remained stable throughout the study in both coinfected and monoinfected patients (Table 2).

Distribution of transaminase levels throughout the study.a

| Timepoint | AST/ALT levels | HCV and/or HBV coinfected | No coinfected | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Normal | 141 (50.5) | 250 (80.1) | <0.001 |

| Grade 1 | 79 (28.3) | 39 (12.5) | ||

| Grade 2 | 45 (16.1) | 20 (6.4) | ||

| Grade 3 | 13 (4.7) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| Grade 4 | 1 (0.4) | 3 (0.6) | ||

| Week 12 | Normal | 128 (50.2) | 237 (81.4) | <0.001 |

| Grade 1 | 83 (32.5) | 39 (13.4) | ||

| Grade 2 | 34 (13.3) | 13 (4.5) | ||

| Grade 3 | 9 (3.5) | 2 (0.7) | ||

| Grade 4 | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | ||

| Week 24 | Normal | 112 (49.1) | 208 (80.9) | <0.001 |

| Grade 1 | 69 (30.3) | 32 (12.5) | ||

| Grade 2 | 35 (15.4) | 14 (5.4) | ||

| Grade 3 | 12 (5.3) | 2 (0.8) | ||

| Grade 4 | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Week 48 | Normal | 104 (47.5) | 205 (82) | <0.001 |

| Grade 1 | 63 (28.8) | 34 (13.6) | ||

| Grade 2 | 44 (20.1) | 8 (3.2) | ||

| Grade 3 | 7 (3.2) | 2 (0.8) | ||

| Grade 4 | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Week 96 | Normal | 69 (50.4) | 139 (82.7) | <0.001 |

| Grade 1 | 41 (29.9) | 23 (13.7) | ||

| Grade 2 | 22 (16.1) | 4 (2.4) | ||

| Grade 3 | 4 (2.9) | 2 (1.2) | ||

| Grade 4 | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | ||

| Linear trend over time | p=0.9656 | p=0.9213 | ||

Grade 1 (AST or ALT 1.25•2.5í ULN); grade 2 (AST or ALT 2.6•5í ULN); grade 3 (AST or ALT 5.1•10í ULN); grade 4 (AST or ALT >10í ULN).

ALT values were missing at different time points: baseline n=95, 14.2%; week 12, n=141, 21.1%; week 24, n=205, 30.7%; week 48, n=226, 33.9%; week 96, n=375, 56.2%. Corresponding figures for AST values were: baseline n=88, 13.2%; week 12, n=137, 20.5%; week 24, n=197, 29.5%; week 48, n=221, 33.1%; week 96, n=371, 55.6%.

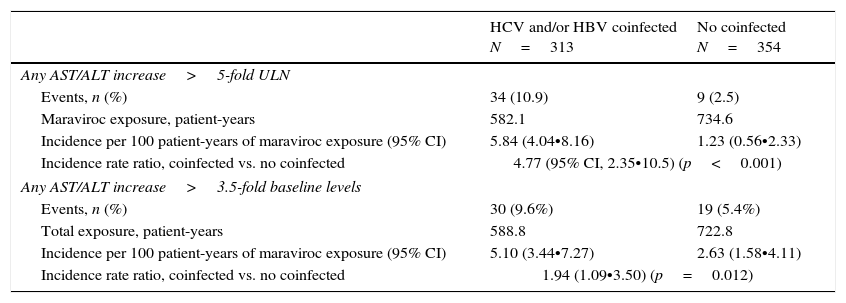

After a median exposure to maraviroc of 20 months (IQR, 12•41), 10.9% of coinfected (n=39) and 2.5% (n=9) HIV-monoinfected patients showed grade ≥3 hypertransaminasemia (p<0.001). Corresponding figures for AST/ALT increase over 3.5-times baseline levels were 9.6% (n=30) and 5.4 (n=19), respectively (p=0.012) (Table 3).

Incidence of grade 3•4 hepatitis along maraviroc treatment.

| HCV and/or HBV coinfected N=313 | No coinfected N=354 | |

|---|---|---|

| Any AST/ALT increase>5-fold ULN | ||

| Events, n (%) | 34 (10.9) | 9 (2.5) |

| Maraviroc exposure, patient-years | 582.1 | 734.6 |

| Incidence per 100 patient-years of maraviroc exposure (95% CI) | 5.84 (4.04•8.16) | 1.23 (0.56•2.33) |

| Incidence rate ratio, coinfected vs. no coinfected | 4.77 (95% CI, 2.35•10.5) (p<0.001) | |

| Any AST/ALT increase>3.5-fold baseline levels | ||

| Events, n (%) | 30 (9.6%) | 19 (5.4%) |

| Total exposure, patient-years | 588.8 | 722.8 |

| Incidence per 100 patient-years of maraviroc exposure (95% CI) | 5.10 (3.44•7.27) | 2.63 (1.58•4.11) |

| Incidence rate ratio, coinfected vs. no coinfected | 1.94 (1.09•3.50) (p=0.012) | |

ULN, upper limit of normality.

Grade 3•4 hepatitis free survival during the first 24 months of follow-up, was significantly higher in HIV mono-infected patients, using the former definition (Fig. 1a), whereas no significant differences were seen in hepatitis free survival using the increase in AST/ALT levels greater than 3.5 times over baseline levels (Fig. 1b) as grade 3•4 hypertransaminasemia definition.

In an analysis adjusted by maraviroc exposure, the risk of AST/ALT increase over 5 times the ULN, per 100 patient-years, was 5.84 (95% CI, 4.04•8.16) and 1.23 (95% CI, 1.23 (0.56•2.33)) in coinfected and HIV-moninfected patients, respectively (incidence rate ratio, 4.77; 95% CI, 2.35•10.05; p<0.001) (Table 3). On the other hand, the risk of AST/ALT increase greater than 3.5-times baseline levels was slightly higher in coinfected patients (incidence rate ratio: 1.94; 95% CI, 1.09•3.50; p=0.012) (Table 3).

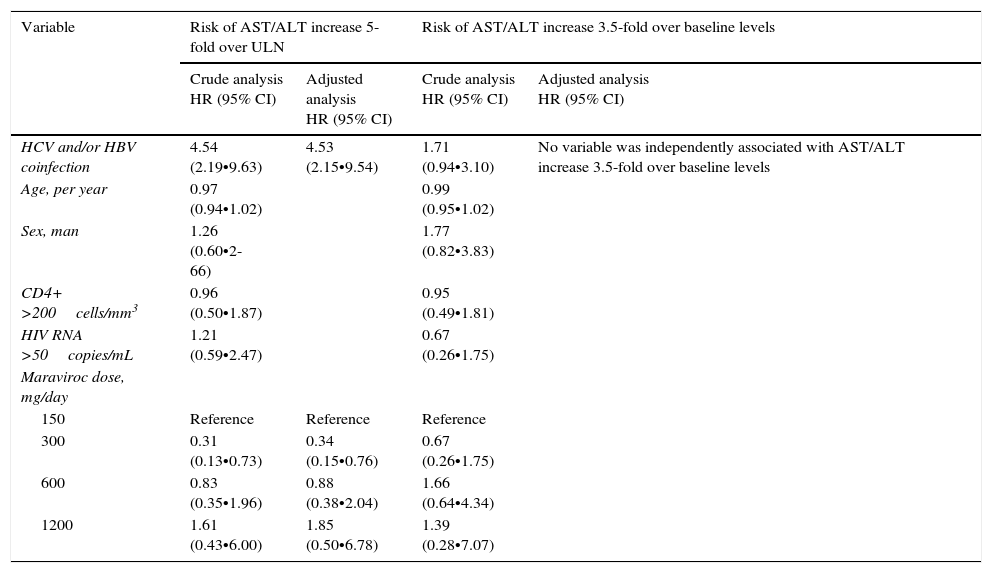

Using a Cox-regression analysis, the adjusted risk of severe hypertransaminasemia (defined as AST/ALT increase over 5-fold the ULN) was 4.53-fold higher among coinfected patients (Table 4). No dose-effect was observed between maraviroc exposure and the risk of grade 3•4 hepatitis. In other model, considering grade 3•4 hepatitis as AST/ALT increase higher than 3.5-times baseline values, no variable, neither HCV and/or HBV-coinfection, was associated with severe hypertransaminasemia (Table 4).

Variables associated with severe hepatitis using Cox proportional hazards models.

| Variable | Risk of AST/ALT increase 5-fold over ULN | Risk of AST/ALT increase 3.5-fold over baseline levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude analysis HR (95% CI) | Adjusted analysis HR (95% CI) | Crude analysis HR (95% CI) | Adjusted analysis HR (95% CI) | |

| HCV and/or HBV coinfection | 4.54 (2.19•9.63) | 4.53 (2.15•9.54) | 1.71 (0.94•3.10) | No variable was independently associated with AST/ALT increase 3.5-fold over baseline levels |

| Age, per year | 0.97 (0.94•1.02) | 0.99 (0.95•1.02) | ||

| Sex, man | 1.26 (0.60•2-66) | 1.77 (0.82•3.83) | ||

| CD4+ >200cells/mm3 | 0.96 (0.50•1.87) | 0.95 (0.49•1.81) | ||

| HIV RNA >50copies/mL | 1.21 (0.59•2.47) | 0.67 (0.26•1.75) | ||

| Maraviroc dose, mg/day | ||||

| 150 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| 300 | 0.31 (0.13•0.73) | 0.34 (0.15•0.76) | 0.67 (0.26•1.75) | |

| 600 | 0.83 (0.35•1.96) | 0.88 (0.38•2.04) | 1.66 (0.64•4.34) | |

| 1200 | 1.61 (0.43•6.00) | 1.85 (0.50•6.78) | 1.39 (0.28•7.07) | |

MRV, maraviroc; ULN, upper limit of normality.

During follow-up, 2 patients (0.3%) discontinued maraviroc because of grade 4 hepatitis and other 2 died due to complications associated to end-stage-liver disease (hepatocarcinoma and hepatic failure, each one).

Outcome of liver fibrosisAmong coinfected patients, 71 (26.3%) out of 270 patients with available data at baseline, had an advanced liver fibrosis (FIB-4 >3.25).

Using a linear mixed effect model, a non statistically significant decrease was seen in the FIB-4 index: ∧0.011 every 12 weeks of treatment with maraviroc (95% CI, ∧0.034 to 0.012; p=0.341). No interaction was detected between FIB-4 index trend and HCV-coinfection. This data suggests no between-group (HIV-monoinfected vs. HCV and/or HBV-coinfected) differences in liver fibrosis over time.

DiscussionIn the present study, including more than 300 patients coinfected with HCV and/or HBV, only 2 patients (0.3%) discontinued maraviroc because of severe hepatitis. In regard with the impact of HCV or HBV coinfection on the risk of hepatitis, the incidence of grade 3•4 hypertransaminasemia, was 5-fold higher in coinfected patients. Notwithstanding, the relative risk in coinfected patients was inferior to 2-fold in the analysis adjusted by baseline levels, when defining grade 3•4 as ASLT/ALT elevation over 3.5-times baseline levels, and no between-group differences were seen in the cumulative proportion of patients showing ASLT/ALT elevation over 3.5-times baseline levels up to 48 weeks of treatment with maraviroc. Indeed, in our study, coinfection with HCV and/or HBV did not influence the overall grade 3•4 liver enzyme levels during the study and was not independently associated with an increased risk of AST/ALT elevation, in the analysis adjusted by baseline levels.

Despite initial concerns regarding the potential hepatic safety of CCR5 antagonists6 analysis of the data up to 48 weeks of treatment with maraviroc in 938 treatment-experienced patients with R5 virus in the MOTIVATE studies did not show a significant difference in grade 3•4 hepatitis between maraviroc and placebo.20 Indeed, in a pooled safety analysis up to 96 weeks of treatment, the exposure-adjusted incidence for grade 3•4 ALT abnormalities, a reliable marker of drug-indeed hepatic injury, was lower in the patients treated with maraviroc once daily, 3.9 per 100 patient-years, or maraviroc twice daily, 2.6 per 100 patient-years, than among patients in the placebo group, 6.5 per 100 patient-years.21 In addition, no significant safety concerns were seen in an extended follow-up analysis of patients enrolled the MOTIVATE trials, over more than 5 years,22 or in the expanded access program.8

However, scarce information was available regarding the hepatic safety of maraviroc in HCV and/or HBV coinfected patients, considered to be at higher risk for ART-associated hepatotoxicity.

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre study, 137 HIV-1-infected subjects, co-infected with HCV and/or HBV, were randomized to maraviroc twice daily (n=70) or placebo (n=67) in combination with a suppressive regimen. In this study, the risk of maraviroc-associated hepatotoxicity was similar to placebo: one subject in each group was reported to have grade 3•4 hepatotoxicity through 48 weeks, the primary safety end-point.23

Liver biopsies were not performed in our study to confirm liver toxicity. Consequently, if elevations in liver enzymes can be attributed to a drug-induced liver damage or a fluctuation of transaminases levels observed during the natural course of chronic HCV infection24 cannot be elucidated.

Furthermore, in keeping with previous data the risk of hepatitis was not associated with the dosing of maraviroc.7

In patients with chronic hepatitis, signaling through CCR5 pathway appears to be an important step in the inflammatory response and in the progression of liver fibrosis.11 Preclinical data suggests that maraviroc, by blocking the CCR5 co-receptor could play a protective role in preventing the progression of liver fibrosis and cancer development.12•15 In our study, liver fibrosis, as evaluated by the FIB-4, a non invasive test that accurately predicts hepatic fibrosis, remained stable over a median follow-time of 20 months, and no differences were seen between monoinfected and coinfected patients. However, we do not have a comparator arm not treated with maraviroc, which could have shown a progression along these 20 months, therefore establishing a difference. Nevertheless, in a study comparing the liver safety of maraviroc with placebo in patients coinfected with placebo, no significant difference in liver fibrosis progression was observed at treatment week 48 in patients receiving maraviroc as compared to those receiving placebo,23 although final 148-week data have not been reported yet.

In addition, preclinical data suggest that maraviroc might protect against the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, a condition relatively common in HCV/HIV coinfected patients, associated with an increased risk of having advanced fibrosis25 However, the impact of maraviroc on hepatic steatosis was not evaluated in our study.

Our study has the limitations of its retrospective design. No biochemical data was available up to the third month of treatment and ALT values were missing in 14•56% of patients throughout the study, which could underestimate the incidence of severe hypertransaminasemia. Also, HCV infection was defined as HCV antibody positivity without assessment of HCV RNA. As 20•30% of patients classified as coinfected with HCV could have spontaneously cleared HCV RNA, this approach could potentially underestimate the risk of hepatitis among HCV-coinfected patients. Moreover, anti-HCV treatment was not recorded but treatment uptake was inferior to 30% in the period when the study was conducted. Finally, consumption of alcohol or other potentially hepatotoxic drugs was not registered during the study. Conversely, the main strength being that is the largest multicenter cohort reported so far evaluating the safety of maraviroc in routine clinical practice in 27 independent centers, including more than 300 patients coinfected with HCV and/or HBV.

In summary, this study demonstrates the long-term safety and tolerability of maraviroc in a large Spanish cohort of patients, with a high prevalence of HCV and/or HBV coinfection. Coinfection with HCV and/or HBV did not influence the maximum liver enzyme level throughout the study, and was not associated with AST/ALT increase over 3.5-times baseline levels. Liver fibrosis, as evaluated by FIB-4 remained stable after a median time treatment with maraviroc of 20 months.

Members of the MVCohort Spain: Jhon Fredy Rojas, Iñaki Pèc)rez, Josep M. Gatell (Hospital Clínic, Barcelona); Isabel Bravo, Jordi Puig, Cristina Herrero, Josep M Llibre (Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona, Barcelona); Loreto Martínez-Dueñas López-Marín, Antonio Rivero (Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía, Córdoba); María Jesús Perez-Elías, Alberto Díaz, David Arroyo, Javier Zamora, Santiago Moreno (Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal, Madrid); Miguel García del Toro, Puri Rubio (Consorcio Hospital General Universitario, Valencia); Juan A. Pineda; Eva Recio (Hospital Universitario Ntra Sra de Valme, Sevilla); Juan Pasquau, Coral García-Valdecillos (Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves); Mar Masià, Catalina Robledano, Fèc)lix Gutièc)rrez (Hospital General Universitario, Elche, Alicante); Manel Crespo, Jordi Navarro, Ariadna Torella (Hospital Universitari Vall d tm)Hebrón, Barcelona); Josèc) Hernández-Quero, Valme Sánchez-Cabrera (Hospital Universitario San Cecilio, Granada); Jesús Sanz (Hospital Universitario La Princesa, Madrid); Manuel Márquez (Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Victoria, Málaga); Antonio Ocampo, Fernando Warncke (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo, Vigo); Josean Iribarren, Miriam Aguado-Atorrasagasti (Hospital Universitario Donostia, San Sebastián); Maria Josèc) Galindo, Ramón Ferrando (Hospital Clínico Universitario, Valencia); Carlos Minguez (Hospital General de Castellón); Daniel Podzamczer, Maria Saumoy (Hospital de Bellvitge, L tm)Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona); Alberto Terrón (Hospital del SAS de Jerez de la Frontera, Cádiz); Josèc) Ramón Arribas, María Yllescas (Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid); Hernando Knobel, Judith Villar (Hospital del Mar, Barcelona); Manuel Fernández-Guerrero (Fundación Jimèc)nez Díaz, Madrid); Pere Domingo, Jessica Muñoz (Hospital Sant Pau, Barcelona); Teodoro Martín (Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro, Majadahonda, Madrid); Juan Miguel Santamaría, Oscar Luis Ferrero (Hospital de Basurto, Bilbao); Mª Rosario Pèc)rez-Simón (Complejo Asistencial Universitario, León); Rafael Torres (Hospital Universitario Severo Ochoa, Leganèc)s, Madrid); Rafael Rubio, Angel Portillo (Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ViiV Healthcare supported the study with an unrestricted grant.