An increase in recent years in the isolation of Vagococcus spp. is suggestive of emerging infection by this pathogen in our hospital.

MethodsProspective, descriptive study. Period: July 2014–January 2019. Phenotypic identification of 15 isolates of Vagococcus spp. was performed by conventional biochemical tests, automated methodology and mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). Molecular identification was achieved by sequencing the 16S rRNA gene. The Vitek™ 2C automated system was used to test antibiotic susceptibility.

ResultsThe molecular method identified 11 Vagococcus fluvialis, one Vagococcus lutrae and three Vagococcus spp. MALDI-TOF MS facilitated the rapid recognition of the genus. The most active antibiotics were ampicillin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, vancomycin, teicoplanin and linezolid. Most of the cases of isolation were associated with skin and soft tissue or osteoarticular infections in patients with diabetes.

ConclusionThis article is the most extensive review of cases of Vagococcus spp. infection reported in the literature and highlights the microbiological and clinical aspects of this pathogen.

En los últimos años un aumento en la frecuencia de aislamiento de Vagococcus spp. estaría indicando la urgencia de la infección por este patógeno en nuestra institución.

MétodosEstudio prospectivo y descriptivo que abarca el periodo de julio de 2014 a enero de 2019. La identificación fenotípica de 15 aislados de Vagococcus spp. se realizó por pruebas bioquímicas convencionales, por metodología automatizada y por espectrometría de masas (MALDI-TOF MS). La identificación molecular por secuenciación del gen ARNr 16S. La sensibilidad antibiótica fue realizada utilizando el sistema automatizado Vitek® 2C.

ResultadosSe identificaron 11 Vagococcus fluvialis, un Vagococcus lutrae y tres Vagococcus spp. por metodología molecular. MALDI-TOF MS permitió el rápido reconocimiento de este género. Los antibióticos más activos fueron ampicilina, <diff id="5" />trimetoprima/sulfametoxazol, vancomicina, teicoplanina y linezolid.

La mayoría mayoría de los aislamientos se asociaron con infecciones en la piel y partes blandas u osteoarticulares en pacientes diabéticos.

ConclusiónEsta comunicación representa la mayor revisión de casos de infecciones por Vagococcus spp. reportados en la literatura, en la que se destacan los aspectos microbiológicos y clínicos de este patógeno.

Vagococcus spp. is a genus of gram-positive, catalase-negative, facultative anaerobic cocci comprising 14 species,1 of which only Vagococcus salmoninarum and Vagococcus fluvialis have been associated with infectious disease in animals. V. fluvialis has been isolated in swine, cattle, cats and horses, and V. salmoninarum in salmonid fish suffering from peritonitis.2 However, their importance as human pathogens remains uncertain, as in most cases they have been isolated in polymicrobial cultures, which means establishing the true role this species plays in infection is difficult.3 In recent years, an increase in the frequency with which Vagococcus spp. have been isolated from clinical samples would seem to indicate the urgency of infection with this pathogen in our institution, a public hospital in the province of Buenos Aires, Argentina.

The objective of this work was to evaluate the microbiological and clinical aspects of Vagococcus spp. isolated from human clinical samples.

MethodsThis is a prospective observational study. Fifteen isolations from human clinical samples (July 2014–January 2019) were analysed at a health centre in the province of Buenos Aires.

Healthcare setting: our institution is a Hospital Interzonal de Agudos (interzonal acute care hospital) located in the north-east of the province of Buenos Aires (Argentina) and is the most advanced hospital in its healthcare region, which covers 14 towns. It has 230 beds and three intensive care units (adult, paediatric and neonatal). Some 20% of admissions to the Internal Medicine Department are due to diabetic foot infection.

Number of soft tissue and bone samples in patients with diabetic foot: our protocol includes taking between three and six samples, with a minimum of three. In most cases (11 out of 13), at least three samples (soft tissue and/or bone) were processed.

Sampling: tissue samples (soft tissues and bone) were taken in theatre by biopsy following surgical debridement and decontamination of the lesion or ulcer.

Phenotype identification: conventional biochemical testing was performed according to the scheme proposed by Christensen and Ruoff,4 based on the following tests: catalase, bile esculin, motility, PYR, leucine aminopeptidase, growth in 6.5% NaCl, at 45 °C and 10 °C, and sensitivity to vancomycin, and the proposal by Texeira et al. to identify species of Enterococcus spp.5 based on arginine hydrolysis, pyruvate use and acid production from mannitol, sorbitol, raffinose, arabinose, alpha-methylglucoside and sucrose.

Identification was also performed on the Vitek® 2C automated system (BioMérieux®) and by mass-spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS, Bruker®, Becton Dickinson®) using a Bruker Daltonics MicroFlex LT® instrument with Biotyper 3.1® (Bruker Daltonics®, Bremen, Germany) software. Based on previous reports6–8 and our own results,9 lower cut-off points than those proposed by the manufacturer for genus- and species-level identification were used: genus- and species-level identification was considered correct with a score ≥1.5 and ≥1.7, respectively, while a score <1.5 was not considered reliable. A validity criterion for interpretation between the first and the next distinct species of the first 10 results with a divergence of 10% was used.8 If this condition was not met, the identification was only considered correct at the genus level.8 Identification by MALDI-TOF MS was considered correct when the result obtained matched the identification results obtained through sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene.

Molecular identification was considered the gold standard and was performed by PCR of 16S rRNA, using Taq DNA polymerase (Promega®) using the primers described by Weisburg et al.10 to obtain the product. Sequencing of the products of both chains was performed using an ABIPrism® 3100 BioAnalyzer at the facilities of Macrogen Inc® (South Korea). The sequences were analysed using BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) and compared with the sequences available in the GenBank database.

Antibiotic sensitivity: this was carried out using the Vitek® 2C automated system (BioMérieux®) with the AST 577 card. The antibiotics assayed were ampicillin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMS), erythromycin, ciprofloxacin, vancomycin, teicoplanin, minocycline, tetracycline and linezolid. For the interpretation of the results, the cut-off points established by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) were used for Enterococcus spp. except in the case of erythromycin, in which those set for the viridans group of Streptococci were used.11

Clinical characteristics: information was collected on age, gender, comorbidities, infection type (mono- or poly-microbial), antibiotic treatment initiated and clinical course, in order to evaluate the role of Vagococcus spp. in human infection. The classification of the Vagococcus spp. isolation in each case was evaluated jointly between the microbiologist and infectious diseases specialist. In general, Vagococcus spp. was classified from a clinical perspective when it was observed in the direct examination and isolated as the sole microorganism in the sample. When it was isolated as part of a polymicrobial microbiota, it was considered an opportunistic pathogen, with the same classification as coagulase-negative staphylococcus, viridans group Streptococcus, Corynebacterium spp. and Enterococcus spp when isolated in a polymicrobial microbiota.12

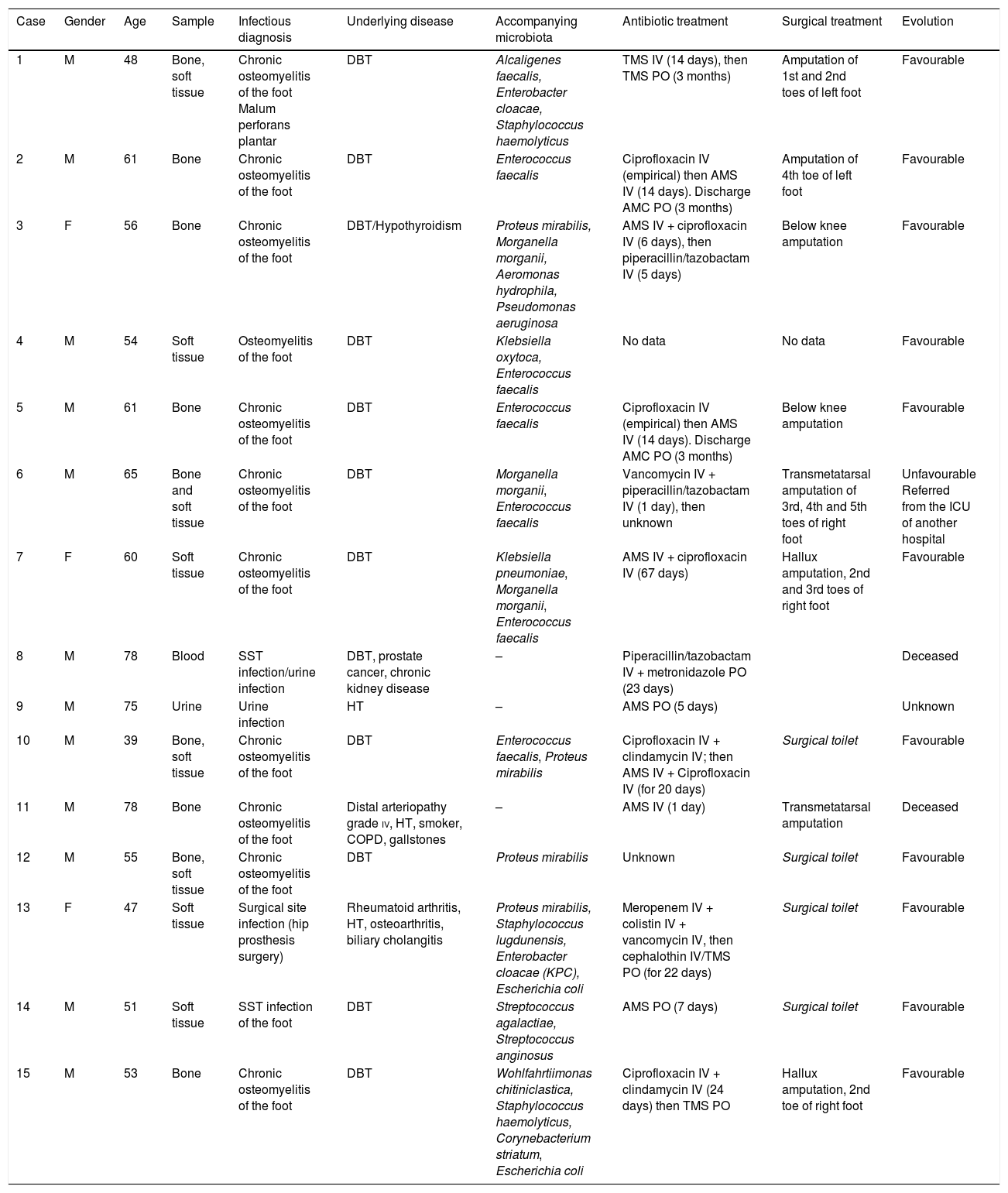

TreatmentThe antibiotics administered and route of administration, as well as the duration of each treatment, varied based on the severity of the infection and are shown in Table 1.

Microbiological and clinical characteristics of the cases with isolation of Vagococcus spp.

| Case | Gender | Age | Sample | Infectious diagnosis | Underlying disease | Accompanying microbiota | Antibiotic treatment | Surgical treatment | Evolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 48 | Bone, soft tissue | Chronic osteomyelitis of the foot Malum perforans plantar | DBT | Alcaligenes faecalis, Enterobacter cloacae, Staphylococcus haemolyticus | TMS IV (14 days), then TMS PO (3 months) | Amputation of 1st and 2nd toes of left foot | Favourable |

| 2 | M | 61 | Bone | Chronic osteomyelitis of the foot | DBT | Enterococcus faecalis | Ciprofloxacin IV (empirical) then AMS IV (14 days). Discharge AMC PO (3 months) | Amputation of 4th toe of left foot | Favourable |

| 3 | F | 56 | Bone | Chronic osteomyelitis of the foot | DBT/Hypothyroidism | Proteus mirabilis, Morganella morganii, Aeromonas hydrophila, Pseudomonas aeruginosa | AMS IV + ciprofloxacin IV (6 days), then piperacillin/tazobactam IV (5 days) | Below knee amputation | Favourable |

| 4 | M | 54 | Soft tissue | Osteomyelitis of the foot | DBT | Klebsiella oxytoca, Enterococcus faecalis | No data | No data | Favourable |

| 5 | M | 61 | Bone | Chronic osteomyelitis of the foot | DBT | Enterococcus faecalis | Ciprofloxacin IV (empirical) then AMS IV (14 days). Discharge AMC PO (3 months) | Below knee amputation | Favourable |

| 6 | M | 65 | Bone and soft tissue | Chronic osteomyelitis of the foot | DBT | Morganella morganii, Enterococcus faecalis | Vancomycin IV + piperacillin/tazobactam IV (1 day), then unknown | Transmetatarsal amputation of 3rd, 4th and 5th toes of right foot | Unfavourable Referred from the ICU of another hospital |

| 7 | F | 60 | Soft tissue | Chronic osteomyelitis of the foot | DBT | Klebsiella pneumoniae, Morganella morganii, Enterococcus faecalis | AMS IV + ciprofloxacin IV (67 days) | Hallux amputation, 2nd and 3rd toes of right foot | Favourable |

| 8 | M | 78 | Blood | SST infection/urine infection | DBT, prostate cancer, chronic kidney disease | – | Piperacillin/tazobactam IV + metronidazole PO (23 days) | Deceased | |

| 9 | M | 75 | Urine | Urine infection | HT | – | AMS PO (5 days) | Unknown | |

| 10 | M | 39 | Bone, soft tissue | Chronic osteomyelitis of the foot | DBT | Enterococcus faecalis, Proteus mirabilis | Ciprofloxacin IV + clindamycin IV; then AMS IV + Ciprofloxacin IV (for 20 days) | Surgical toilet | Favourable |

| 11 | M | 78 | Bone | Chronic osteomyelitis of the foot | Distal arteriopathy grade iv, HT, smoker, COPD, gallstones | – | AMS IV (1 day) | Transmetatarsal amputation | Deceased |

| 12 | M | 55 | Bone, soft tissue | Chronic osteomyelitis of the foot | DBT | Proteus mirabilis | Unknown | Surgical toilet | Favourable |

| 13 | F | 47 | Soft tissue | Surgical site infection (hip prosthesis surgery) | Rheumatoid arthritis, HT, osteoarthritis, biliary cholangitis | Proteus mirabilis, Staphylococcus lugdunensis, Enterobacter cloacae (KPC), Escherichia coli | Meropenem IV + colistin IV + vancomycin IV, then cephalothin IV/TMS PO (for 22 days) | Surgical toilet | Favourable |

| 14 | M | 51 | Soft tissue | SST infection of the foot | DBT | Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus anginosus | AMS PO (7 days) | Surgical toilet | Favourable |

| 15 | M | 53 | Bone | Chronic osteomyelitis of the foot | DBT | Wohlfahrtiimonas chitiniclastica, Staphylococcus haemolyticus, Corynebacterium striatum, Escherichia coli | Ciprofloxacin IV + clindamycin IV (24 days) then TMS PO | Hallux amputation, 2nd toe of right foot | Favourable |

AMC: amoxicillin-clavulanic acid; AMS: ampicillin-sulbactam; DBT: diabetes mellitus; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HT: hypertension; IV: intravenous administration; SST: skin and soft tissue; TMS: trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; ICU: intensive care unit; PO: per os (oral) administration.

The amplification and subsequent sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene identified 11 isolations as V. fluvialis, one as V. lutrae, and in three cases molecular identification could only be achieved at the genus level since this methodology did not discriminate between V. fluvialis and V. carnophilus.

Given the phenotypical similarity between the various species, identification with conventional biochemical testing was only possible at the genus level.

Although mass spectrometry was able to provide molecular identification in 11 V. fluvialis isolates, the three isolates identified only at genus level by the reference method were identified as V. fluvialis with scores >2.0 by mass spectrometry. In spite of having obtained a reliable score at species level, identification using this methodology was only considered correct at genus level, as V. carnophilus is not found in the equipment's database. The only isolate identified as V. lutrae by the molecular method was identified at species level by MALDI-TOF MS.

With regard to the VITEK® C2 automated system, unlike in the molecular identification, all isolates were identified as V. fluvialis, therefore identification by this method was only considered correct at genus level.

The majority of the Vagococcus spp. findings (13/15) corresponded to infections located in the skin and soft tissues/bone; the two remaining isolates came from urine and blood cultures.

The single Vagococcus lutrae in blood was in a 77-year-old diabetic patient with a history of prostate cancer in chemotherapy treatment, who was admitted due to poor clinical progression. The patient presented two probable foci of infection as the source of the bacteraemia – urine and skin/soft tissue. Extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing K. pneumoniae only sensitive to amikacin and carbapenems was isolated from the urine, but the soft tissue sample (cellulitis of the instep) was unfortunately not sent for culture. The patient's condition worsened and he died.

With regard to clinical characteristics, the age range was from 39 to 78 years, with 12 male and 3 female patients.

In 12 cases, Vagococcus spp. was isolated with accompanying microbiota (Table 1).

Twelve of the 15 patients presented diabetes mellitus as the underlying illness (Table 1). Two patients died.

The most active antibiotics were ampicillin, TMS, vancomycin, teicoplanin and linezolid, with an MIC50 (μg/mL) of <2.0, <2.0, 2, 0.5 and 1.0, respectively. Resistance to fluoroquinolones was observed in six isolates, with an MIC50 of 1.0 μg/mL and MIC90 of 8.0 μg/mL. Twelve of the 15 isolates were resistant to tetracyclines, with an MIC50 of 16 μg/mL. Macrolides presented low activity (only four of the 15 isolates were sensitive) (MIC50 and MIC90 of 1.0 μg/mL).

DiscussionThe first evidence of a connection between V. fluvialis and possible human infections was communicated by Teixeira et al. in 1997.13 They reported the isolation of this species in the peritoneal fluid of a patient with kidney disease, from an infected wound in a patient bitten by a lamb, and in blood cultures from two patients for whom no additional information is available regarding their clinical status or associated disease.13 Two decades later, in 2008, Al-Ahmad et al. reported the isolation of V. fluvialis as part of a mixed endodontic infection in a patient with an infected root canal.14 More recently, Jadhav et al. described a case of endocarditis due to this species in a 70-year-old patient with severe aortic regurgitation who required valve replacement.15

With regard to other species, in 2016. García et al. communicated the first clinical isolation of Vagococcus lutrae (a species isolated in otters), from macerated lesions in the skin of a morbidly obese patient in France.16 The second isolation of this species from a human infection and the first in blood, from an elderly patient with skin lesions as a probable focus of infection, was reported recently by Altintas et al.17

In August 2019, Shewmaker et al. described the isolation of a new species: Vagococcus vulneris in a wound on the foot.18

The isolation of Vagococcus lutrae from blood in this study is only the second report of isolation of this species in blood and the third from a human infection in the literature. Unfortunately, it was not possible to establish whether the skin and soft tissue infection was the focus of the bacteraemia, or whether this was a contaminant, as the microorganism was isolated in one of the two blood culture bottles.

The presence of diabetes as the underlying illness in 12 of the 15 patients in whom Vagococcus spp. were isolated is notable. This association has not previously been mentioned in the literature and opens a new door for research.

We are of the view that the reported cases of Vagococcus may be underestimated as the microorganism is often incorrectly identified as Enterococcus spp. by conventional biochemical tests due to the similarity of their biological profiles.5,13 The advent of MALDI-TOF MS mass spectrometry and its growing global use will enable this genus to be quickly identified and its true role in human infection established.

Our work included the study of 15 isolates of Vagococcus spp., making it the work with the highest number of cases described in the literature Its isolation primarily from skin, soft tissue and bone infections in diabetic patients opens a door for research into a possible association between Vagococcus spp. infections and patients with metabolic diseases.

FundingThis study was financed with funds from the UBACYT 2018 Project Model i: Code 20020170100109BA.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Racero L, Barberis C, Traglia G, Loza MS, Vay C, Almuzara M. Infecciones por Vagococcus spp. Aspectos microbiológicos y clínicos y revisión de la literatura. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2021;39:335–339.