Paediatric infective endocarditis (IE) is a serious condition associated with significant mortality. Information in Spain is limited and comes from case series from single centres. The aim was to describe the epidemiology, clinical features, microbiology and outcome of paediatric IE in Andalusia.

Patients and MethodsMulti-centre descriptive observational retrospective study of patients <18 years old with a diagnosis of IE who were admitted to six Andalusian hospitals during 2008−2020.

Results44 episodes of IE (41 patients) with a median age of 103 months (IQR 37−150 months) were identified. Congenital heart disease (CHD) was the main predisposing factor, identified in 34 cases (77%). A total of 21 (48%) episodes of IE occurred in patients with prosthetic material. These had higher rate of CHD (p = 0.002) and increased end organ dysfunction (p = 0.04) compared to those with native valve.

Fever was an almost universal symptom, associated in 23% of the episodes with heart failure. Staphylococcus aureus (25%) followed by coagulase-negative staphylococci (18%) and Streptococcus viridans (14%) were the most frequently isolated microorganisms, and three (7%) patients with central venous catheters had a fungal infection.

Thromboembolic events were observed in 30% of the episodes, surgical intervention was required in 48% of cases. Mortality rate was 9%. Prosthetic material and CRP > 140 mg/L were independent predictors of complicated IE.

ConclusionsOur findings emphasize the high morbidity of paediatric IE. The information provided could be useful for the identification of epidemiological and clinical profiles of children with IE and complicated forms.

La endocarditis infecciosa (EI) pediátrica es un cuadro grave con mortalidad significativa. La información en España es limitada y procede de series de casos de centros únicos. El objetivo fue describir la epidemiología, clínica, microbiología y resultados de la EI pediátrica en Andalucía.

Pacientes y métodosEstudio descriptivo observacional retrospectivo multicéntrico de pacientes < 18 años con diagnóstico de EI en 6 hospitales andaluces durante el periodo 2008−2020.

ResultadosSe identificaron 44 episodios de EI (41 pacientes) con mediana de edad de 103 meses (RIQ 37−150 meses). Las cardiopatías congénitas (CC) fueron el principal factor predisponente, presente en 34 casos (77%). Un total de 21 (48%) episodios de EI ocurrieron en pacientes con material protésico. Estos tuvieron una mayor tasa de CC (p = 0.002) y disfunción orgánica (p = 0.04) que aquellos con válvula nativa.

La fiebre fue un síntoma prácticamente universal asociada con insuficiencia cardíaca en un 23% de los episodios. Staphylococcus aureus (25%), estafilococos coagulasa negativos (18%) y Streptococcus viridans (14%) fueron los microorganismos aislados con mayor frecuencia y tres (7%) pacientes portadores de catéter venoso central tuvieron una infección fúngica.

Se observaron complicaciones tromboembólicas en un 30% de episodios, tuvieron requerimientos quirúrgicos un 48% de casos. La mortalidad fue de un 9%. El material protésico y la PCR > 140 mg/L fueron predictores independientes de EI complicada.

ConclusionesLos hallazgos del estudio subrayan la elevada morbilidad de la EI pediátrica. La información generada podría favorecer la identificación de los perfiles epidemiológicos y clínicos de los niños con EI y formas complicadas.

Infective endocarditis (IE) in the paediatric age group is a major clinical problem.1,2 Although the incidence of IE in children is low, the associated morbidity and mortality rates are significant.1–5 As IE is a complex and difficult condition to treat, management of IE in specialised centres by an experienced multidisciplinary IE team is recommended.6 It is therefore important for us to keep up-to-date with in-depth knowledge about the epidemiology, microbiology, clinical features, prognostic factors, prevention and treatment of IE, some of which may have changed in recent years.

The information published in the literature on paediatric IE is limited and of low methodological quality, coming almost exclusively from descriptive observational studies, most often carried out in single centres; it includes three series of cases previously reported here in Spain, two of which are from the same centre.1,5,7–11 The aim of this first multicentre study on IE in the paediatric age group conducted in Spain was to describe the epidemiology, clinical features, microbiology and outcomes in paediatric patients diagnosed with IE in six tertiary care hospitals in the region of Andalusia.

Patients and methodsCasesThe Red de Endocarditis Pediátrica Andaluza (REPA) [Andalusian Paediatric Endocarditis Network] is a multicentre collaborative group which retrospectively and prospectively collects data on episodes of IE in hospitals in Andalusia, Spain. We conducted a retrospective descriptive observational study of patients with paediatric IE treated at six tertiary care hospitals in Andalusia, Spain: Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío (HUVR), Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga (HURM), Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía (HURS), Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez (HJRJ), Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves (HVN) and Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar (HUPM). The study period was from January 2008 to December 2020.

Inclusion criteriaMedical records containing the term endocarditis in patients <18 years of age under the diagnostic impression were selected from the hospital care electronic database of the Andalusian Public Health Service. This strategy was complemented by a search for additional cases in the six participating hospitals' internal databases of the Paediatric Infectious Diseases and Cardiology sections. The selected medical records were reviewed by the study investigators. Finally, we selected all the cases that met the criteria for definite or possible IE according to the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)-modified Duke Criteria.6

Variables included in the study and definitionsDemographic variables, predisposing factors, clinical manifestations, microbiological and laboratory findings, treatment and clinical outcome, were described and analysed. The demographic variables and predisposing factors included were: age, gender; previous medical history, underlying heart disease; previous surgical intervention; devices at the time of diagnosis; and echocardiographic findings. Haemoglobin and CRP values and leucocyte, neutrophil and platelet counts were included as laboratory findings. Lastly, information was collected on the duration of empirical, directed and total antibiotic treatment, the need for and type of surgical treatment and the time from diagnosis to surgical intervention, and the final outcome.

An episode of IE was defined as associated with health care when the episode occurred ≥48 h after hospital admission or the patient had a central venous catheter (CVC) or a history of cardiac catheterisation or surgery in the 30 days before the diagnosis of IE.

Patients with cardiac prosthetic material, such as shunts or conduits, prosthetic valves and implantable cardiac devices (for example, defibrillators), were included in the prosthetic material group.

An organism was considered causal when it was identified in at least two blood cultures or a surgical sample culture.

An episode of IE was categorised as complicated when, during its course, it produced any of the following outcomes: death, need for surgery, evidence of thromboembolic manifestations, and organ dysfunction.

Pathogens identified in IE cases other than coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS), Streptococcus viridans, Corynebacterium pseudodiphtericum and Kingella kingae were included in the group of pathogens with greater virulence.

Statistical analysisStatistical processing was performed using the SSPS 26.0 package. Descriptive statistics were performed using absolute and relative frequencies and univariate analysis of the association between the characteristics of the cases and whether or not they had any implanted prosthetic material. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 and Fisher's exact tests, as appropriate. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables, and a multivariate analysis was performed of independent predictors associated with the development of complicated IE. Initially, a bivariate analysis was performed of potential predictors of complicated IE: age <3 years; duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis <9 days; prosthetic material; CRP > 140 mg/l; and infections by germs with increased virulence. Variables with a p-value <0.10 in this bivariate analysis were subsequently entered into a binary logistic regression model. In all models, a significant test was considered when the p-value was <0.05.

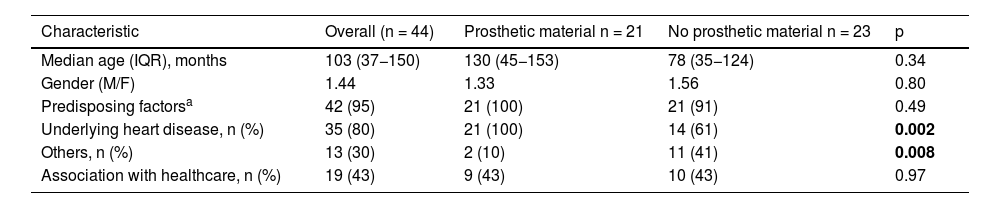

ResultsDemographic characteristicsDuring the study period, 44 episodes of IE were identified in 41 paediatric patients. One female patient with prosthetic material had three episodes of IE reinfection with a time interval of >6 months after a previous episode and different aetiologies. The 41 patients were treated at the following hospitals: HUVR (n = 18), HURM (n = 10), HURS (n = 5), HUPM (n = 3), HVN (n = 3) and HJRJ (n = 2). The median age was 103 months (IQR 37−150 months), and the disease was more common in males (M/F: 1.44) (Table 1).

Demographic characteristics of the 44 episodes of infective endocarditis (IE) in six Andalusian tertiary hospitals in the period 2008-2020.

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 44) | Prosthetic material n = 21 | No prosthetic material n = 23 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (IQR), months | 103 (37−150) | 130 (45−153) | 78 (35−124) | 0.34 |

| Gender (M/F) | 1.44 | 1.33 | 1.56 | 0.80 |

| Predisposing factorsa | 42 (95) | 21 (100) | 21 (91) | 0.49 |

| Underlying heart disease, n (%) | 35 (80) | 21 (100) | 14 (61) | 0.002 |

| Others, n (%) | 13 (30) | 2 (10) | 11 (41) | 0.008 |

| Association with healthcare, n (%) | 19 (43) | 9 (43) | 10 (43) | 0.97 |

Significant p-values are shown in bold.

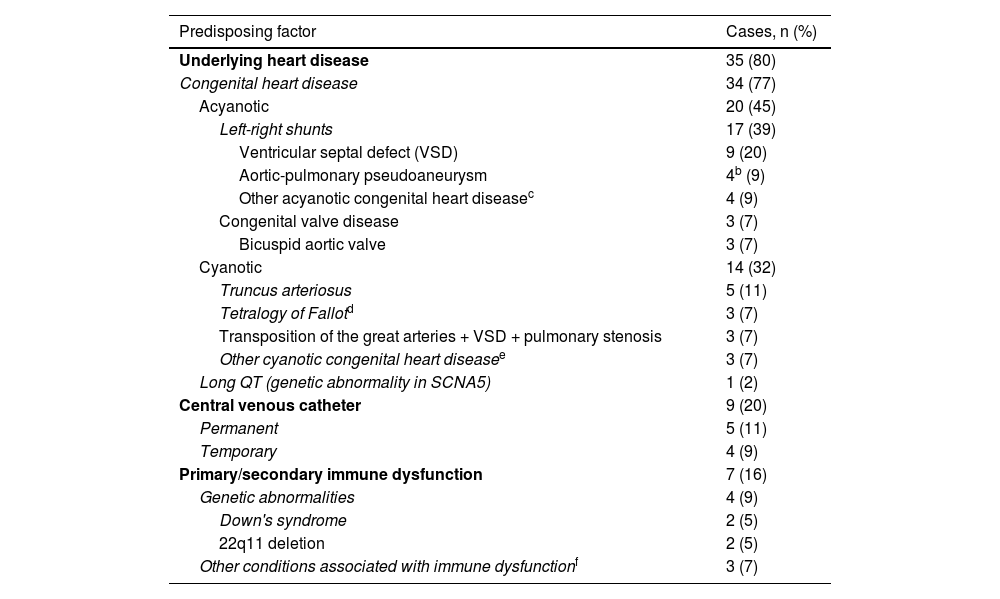

A total of 42 (95%) episodes had associated predisposing factors; in 35 (80%), there was a history of underlying heart disease, and in 13 (30%), other predisposing factors (some episodes were associated with more than one predisposing factor) (Table 2). At a more specific level, the following predisposing factors were identified: 34 (77%) episodes with CHD; nine (20%) episodes in patients with a central venous catheter (CVC); seven (15%) episodes with immune dysfunction; and one (2%) episode associated with long QT in a patient with a dual-chamber implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD). Of the 34 episodes with CHD, 20 (45%) of the cases had acyanotic heart disease and 14 (32%) cyanotic (Table 2). The most prevalent acyanotic CHD were (n, %): ventricular septal defect (VSD) (9; 20%); aortic-pulmonary pseudoaneurysms (4; 9%) (described in a single patient); and bicuspid aortic valve (3; 7%). The most commonly identified cyanotic heart diseases were (n; %): truncus arteriosus (TA) (5; 11%); and tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) (3; 7%). The disorders associated with immune dysfunction were two (5%) cases of Down's syndrome and DiGeorge syndrome (22q11 deletion syndrome) and a single case (2%) of Wilms tumour, kidney transplant and extreme prematurity.

Predisposing factors in the 42 episodes of infective endocarditis (IE) in the period 2008–2020.a

| Predisposing factor | Cases, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Underlying heart disease | 35 (80) |

| Congenital heart disease | 34 (77) |

| Acyanotic | 20 (45) |

| Left-right shunts | 17 (39) |

| Ventricular septal defect (VSD) | 9 (20) |

| Aortic-pulmonary pseudoaneurysm | 4b (9) |

| Other acyanotic congenital heart diseasec | 4 (9) |

| Congenital valve disease | 3 (7) |

| Bicuspid aortic valve | 3 (7) |

| Cyanotic | 14 (32) |

| Truncus arteriosus | 5 (11) |

| Tetralogy of Fallotd | 3 (7) |

| Transposition of the great arteries + VSD + pulmonary stenosis | 3 (7) |

| Other cyanotic congenital heart diseasee | 3 (7) |

| Long QT (genetic abnormality in SCNA5) | 1 (2) |

| Central venous catheter | 9 (20) |

| Permanent | 5 (11) |

| Temporary | 4 (9) |

| Primary/secondary immune dysfunction | 7 (16) |

| Genetic abnormalities | 4 (9) |

| Down's syndrome | 2 (5) |

| 22q11 deletion | 2 (5) |

| Other conditions associated with immune dysfunctionf | 3 (7) |

A history of prior cardiac surgery was documented in 22 (63%) of the 35 episodes with heart disease, and surgery was performed a median of 84 days (IQR 21−1,368 days) before the onset of the IE. Fewer than half (43%) of the IE episodes were associated with health care.

According to the clinical characteristics and echocardiographic findings, 21 (48%) of the 44 episodes of IE occurred in patients with cardiac prosthetic material: biological prosthetic valve (n = 11); transannular patch (n = 6); metallic prosthetic valve (n = 3); and dual-chamber ICD (n = 1). Comparison of IE episodes between these patients and those without prosthetic material showed a higher proportion of underlying heart disease in the first group (p = 0.002) and other predisposing factors in the second group (p = 0.008). No significant differences were found between the two groups for the other demographic variables analysed.

Clinical manifestationsThe 44 episodes of IE were classified as 40 (91%) episodes of definite endocarditis and four (9%) episodes of possible endocarditis. The location of the lesions in IE affected the right chambers in 24 (55%) episodes, the left chambers in 16 (36%) episodes, and in four (9%) cases, the involvement was bilateral.

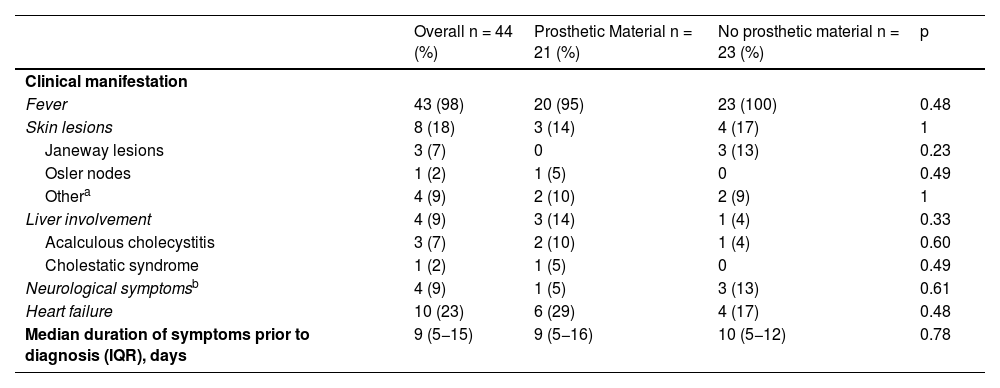

Fever was an almost universal symptom documented in 43 (98%) of the 44 sets of medical records (Table 3). Other symptoms described in the clinical presentation were, in order of prevalence: heart failure in 10 (23%) episodes; skin lesions in eight (18%) episodes (Janeway lesions in three [7%] and one [2%] episode with Osler nodes, septal panniculitis, petechial rash, maculopapular rash and urticarial rash); and liver involvement and neurological symptoms in four (9%) episodes, with the liver involvement in three (7%) of these cases being the result of acalculous cholecystitis.

Clinical manifestations of the 44 episodes of infective endocarditis (IE).

| Overall n = 44 (%) | Prosthetic Material n = 21 (%) | No prosthetic material n = 23 (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical manifestation | ||||

| Fever | 43 (98) | 20 (95) | 23 (100) | 0.48 |

| Skin lesions | 8 (18) | 3 (14) | 4 (17) | 1 |

| Janeway lesions | 3 (7) | 0 | 3 (13) | 0.23 |

| Osler nodes | 1 (2) | 1 (5) | 0 | 0.49 |

| Othera | 4 (9) | 2 (10) | 2 (9) | 1 |

| Liver involvement | 4 (9) | 3 (14) | 1 (4) | 0.33 |

| Acalculous cholecystitis | 3 (7) | 2 (10) | 1 (4) | 0.60 |

| Cholestatic syndrome | 1 (2) | 1 (5) | 0 | 0.49 |

| Neurological symptomsb | 4 (9) | 1 (5) | 3 (13) | 0.61 |

| Heart failure | 10 (23) | 6 (29) | 4 (17) | 0.48 |

| Median duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis (IQR), days | 9 (5−15) | 9 (5−16) | 10 (5−12) | 0.78 |

The median duration of symptoms before diagnosis was nine days (IQR 5−15 days). The episode with the longest delay in diagnosis (108 days) occurred in a patient with VSD with very mild and nonspecific symptoms of low-grade fever and arthralgia and a history of several cycles of oral antibiotic therapy. The clinical symptoms and duration before diagnosis were similar in the groups with and without prosthetic material (Table 3).

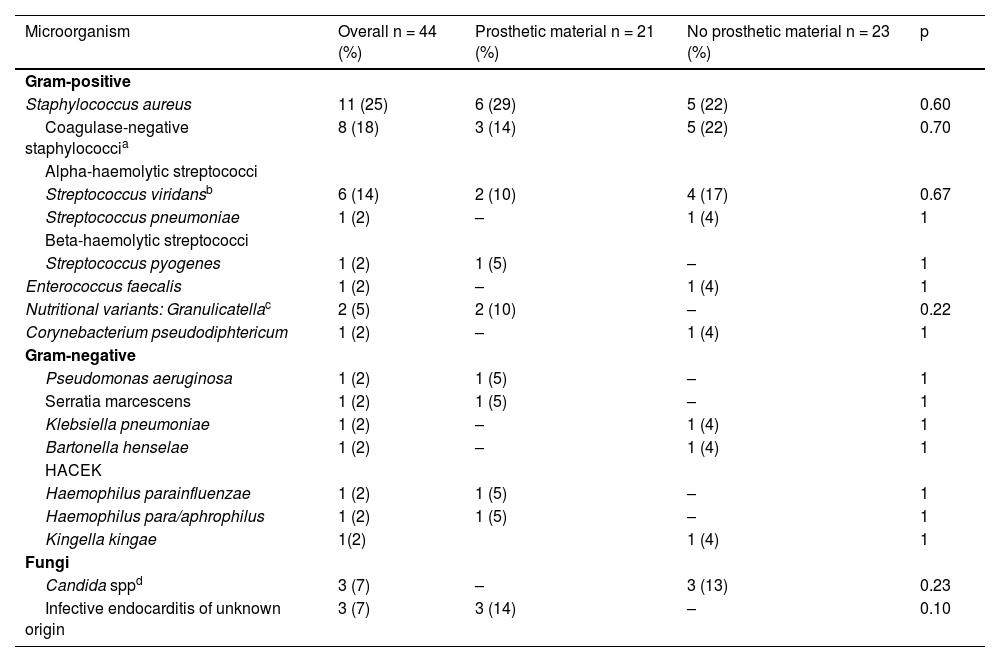

Microbiological findingsDuring the study period, the pathogens causing IE were identified in 41 (93%) of the 44 episodes. The most prevalent microorganisms in order of frequency (n; %) were: Staphylococcus aureus (11; 24%), Staphylococcus epidermidis (8; 18%), Streptococcus viridans (6; 14%), Candida spp. (3; 7%) and Granulicatella spp. (2; 5%). The rest of the identified microorganisms were isolated in one single episode (Table 4). Methicillin resistance rates in staphylococcal infections were 9% for S. aureus and 50% for S. epidemidis.

Microbiological findings of the 44 episodes of infective endocarditis (IE).

| Microorganism | Overall n = 44 (%) | Prosthetic material n = 21 (%) | No prosthetic material n = 23 (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-positive | ||||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 11 (25) | 6 (29) | 5 (22) | 0.60 |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococcia | 8 (18) | 3 (14) | 5 (22) | 0.70 |

| Alpha-haemolytic streptococci | ||||

| Streptococcus viridansb | 6 (14) | 2 (10) | 4 (17) | 0.67 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 1 (2) | – | 1 (4) | 1 |

| Beta-haemolytic streptococci | ||||

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 1 (2) | 1 (5) | – | 1 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 1 (2) | – | 1 (4) | 1 |

| Nutritional variants: Granulicatellac | 2 (5) | 2 (10) | – | 0.22 |

| Corynebacterium pseudodiphtericum | 1 (2) | – | 1 (4) | 1 |

| Gram-negative | ||||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1 (2) | 1 (5) | – | 1 |

| Serratia marcescens | 1 (2) | 1 (5) | – | 1 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 1 (2) | – | 1 (4) | 1 |

| Bartonella henselae | 1 (2) | – | 1 (4) | 1 |

| HACEK | ||||

| Haemophilus parainfluenzae | 1 (2) | 1 (5) | – | 1 |

| Haemophilus para/aphrophilus | 1 (2) | 1 (5) | – | 1 |

| Kingella kingae | 1(2) | 1 (4) | 1 | |

| Fungi | ||||

| Candida sppd | 3 (7) | – | 3 (13) | 0.23 |

| Infective endocarditis of unknown origin | 3 (7) | 3 (14) | – | 0.10 |

The aetiological agents responsible for the infections were similar in the groups with and without prosthetic material. It should be noted, however, that the three cases of fungal infection occurred in patients without prosthetic material but with CVC.

Laboratory findingsThe mean (± SD) haemoglobin and CRP levels were 10.8 (± 4.4) and 140 (± 106) mg/l, respectively, and leucocyte and neutrophil counts were 12,270 (± 6,156) and 8,546 (± 5,855) cells/μl respectively. Prosthetic material infections had higher leucocyte counts, neutrophil counts and mean CRP values and lower platelet counts than cases of infection without prosthetic material, but without reaching statistical significance.

Imaging testsTransthoracic ultrasound was performed in all episodes, and 18F-FDG-PET/CT was also performed in nine (20%) episodes; seven (16%) of these episodes occurred in patients with prosthetic material, and with transoesophageal ultrasound in three (7%) episodes.

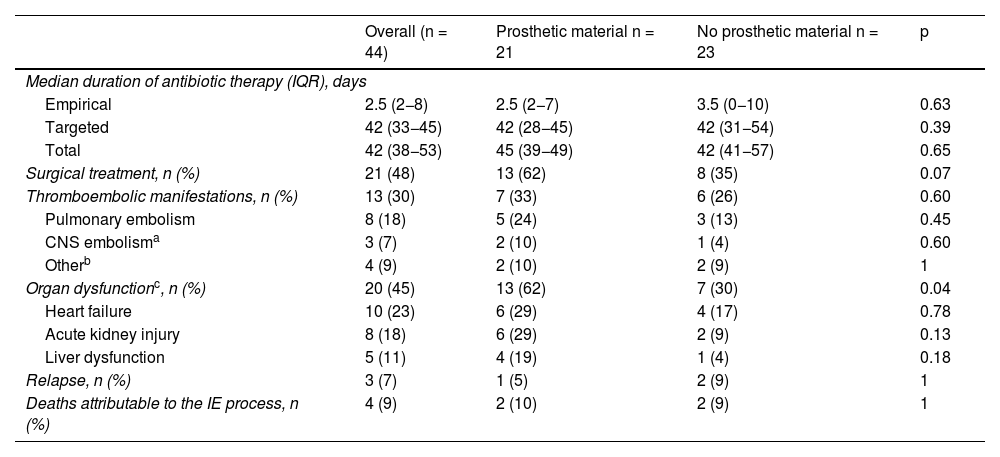

Treatment and clinical outcomeEmpirical antimicrobial treatment was varied according to individual circumstances. In the episode of methicillin-resistant S. aureus infection, empirical treatment was inconsistent because it was based on beta-lactams and was subsequently optimised after the blood culture and antimicrobial susceptibility results. Targeted antimicrobial treatment was usually carried out by the guidelines recommended in the clinical reference guidelines for managing IE. Most of the episodes in more recent years were included in programmes for optimising the use of antimicrobials. In the 44 episodes of IE, the median durations of total, empirical and targeted antibiotic therapy were, respectively, 42 days (IQR: 38–52 days), two days (IQR: 2−8 days) and days (IQR: 33−45 days), while the mean values (± SD) corresponding to these same variables were 47.5 (± 29) days, 5.9 (± 9.2) days and 45.4 (± 27.6) days (Table 5). The median duration of total antibiotic therapy was similar in the IE of the right and left chambers (42 vs 45 days, p = 0.94) and in the complicated and uncomplicated IE (50 vs 38 days; p = 0.38).

Treatment and clinical outcome of the 44 episodes of infective endocarditis (IE).

| Overall (n = 44) | Prosthetic material n = 21 | No prosthetic material n = 23 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median duration of antibiotic therapy (IQR), days | ||||

| Empirical | 2.5 (2−8) | 2.5 (2−7) | 3.5 (0−10) | 0.63 |

| Targeted | 42 (33−45) | 42 (28−45) | 42 (31−54) | 0.39 |

| Total | 42 (38−53) | 45 (39−49) | 42 (41−57) | 0.65 |

| Surgical treatment, n (%) | 21 (48) | 13 (62) | 8 (35) | 0.07 |

| Thromboembolic manifestations, n (%) | 13 (30) | 7 (33) | 6 (26) | 0.60 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 8 (18) | 5 (24) | 3 (13) | 0.45 |

| CNS embolisma | 3 (7) | 2 (10) | 1 (4) | 0.60 |

| Otherb | 4 (9) | 2 (10) | 2 (9) | 1 |

| Organ dysfunctionc, n (%) | 20 (45) | 13 (62) | 7 (30) | 0.04 |

| Heart failure | 10 (23) | 6 (29) | 4 (17) | 0.78 |

| Acute kidney injury | 8 (18) | 6 (29) | 2 (9) | 0.13 |

| Liver dysfunction | 5 (11) | 4 (19) | 1 (4) | 0.18 |

| Relapse, n (%) | 3 (7) | 1 (5) | 2 (9) | 1 |

| Deaths attributable to the IE process, n (%) | 4 (9) | 2 (10) | 2 (9) | 1 |

In addition to antibiotic therapy, a total of 21 (48%) episodes required surgical treatment (performed a mean of 38 [± 39] days after IE diagnosis). The most common indications for surgical treatment were uncontrolled infection (48%) and valvular dysfunction with heart failure (38%).

Thromboembolic manifestations were identified in 13 (30%) episodes, of which eight (17%) cases were pulmonary embolisms, three (7%) were central nervous system (CNS) embolisms, and four (9%) were in other locations, including two episodes associated with pulmonary and CNS involvement. The rate of thromboembolic complications was higher in IE episodes caused by S. aureus than other infectious causes, but without reaching statistical significance (45% vs 24%, p = 0.16). Five thromboembolic manifestations were diagnosed by 18F-FDG-PET/TC, performed in only nine cases of IE. Fewer than half (45%) of the IE cases were associated with organ dysfunction, the most common being heart failure (n = 10; 23%), followed by acute kidney injury (AKI)(n = 8; 18%) and liver dysfunction (LD) (n = 5; 11%).

The episodes with poor outcomes included four (9%) deaths attributable to IE, three (7%) relapses with subsequent favourable responses to treatment and four (9%) cases of cure with sequelae.

The group of episodes associated with prosthetic material had a higher rate of organ dysfunction (62% vs 30%; p = 0.04) than that found in the episodes without prosthetic material, with the proportion of episodes with AKI and LD being three and four times higher, respectively. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in the proportions of thromboembolic manifestations and surgical requirements.

Multivariate analysis: variables predictive of complicated IETwenty-eight (64%) episodes were categorised as complicated IE. A significant association was found by bivariate analysis between complicated IE and the presence of prosthetic material (p = 0.005), with no statistically significant differences found for the rest of the predictor variables analysed: age <3 years; duration of symptoms before diagnosis <9 days; CRP > 140 mg/l (p = 0.05); and infections by germs with increased virulence (as specified in the patients and methods section) (Appendix B Supplementary material Table). Independent predictors of complicated IE by multivariate analysis using a binary logistic regression model were prosthetic material (OR: 6.2; 95% CI: 1.2–31.8; p = 0.03) and CRP > 140 mg/l (OR: 7.3; 95% CI: 1.4–40; p = 0.02).

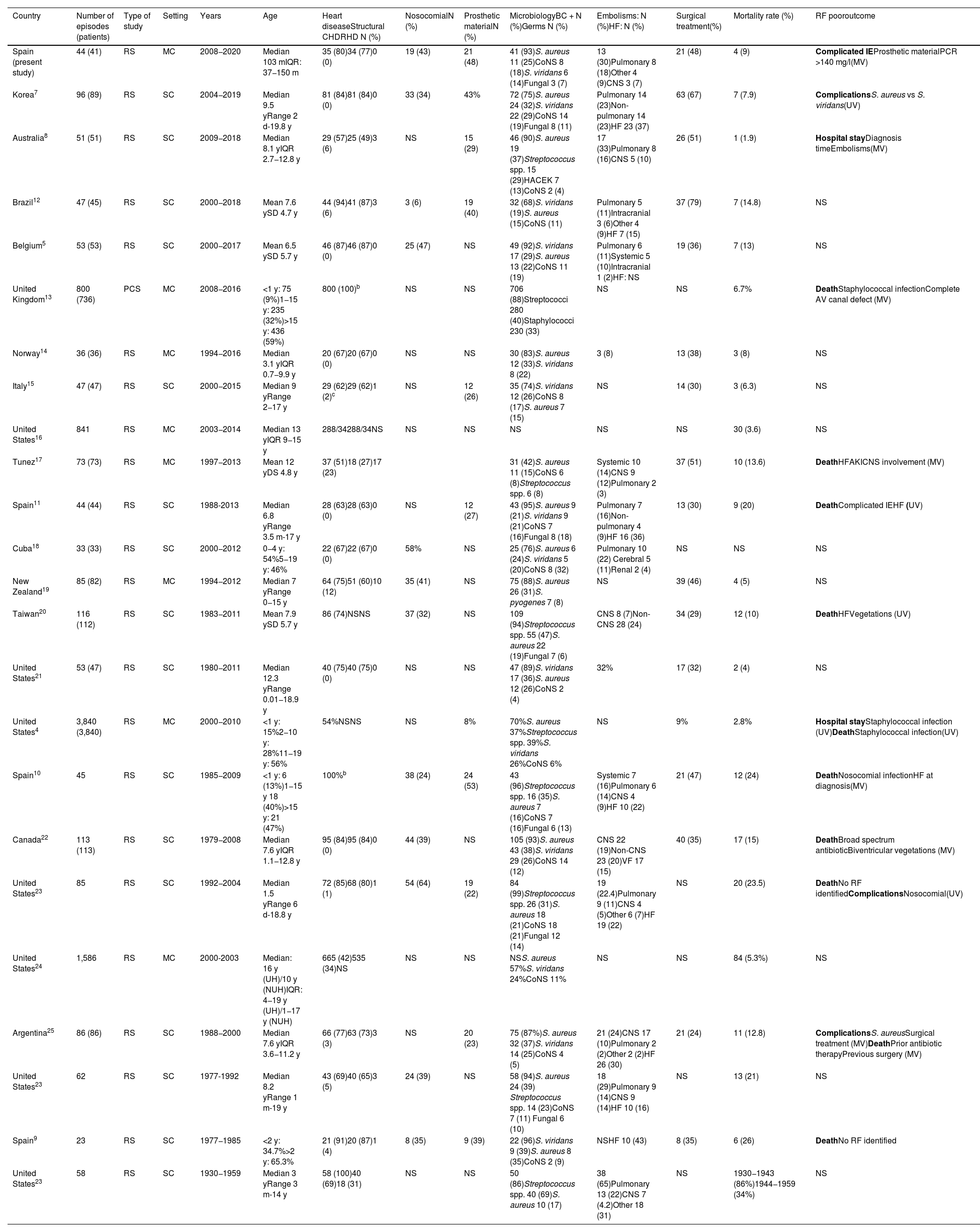

DiscussionThis study illustrates the epidemiology, microbiological aetiology, clinical features and outcome of a series of cases of IE in paediatric patients admitted to six of the main tertiary hospitals in Andalusia, Spain. The most significant findings are summarised in Table 6, and the studies published on paediatric IE since 2000 and an additional previous study from here in Spain are included for comparison.4,5,7–25

Summary of epidemiological characteristics, microbiology and outcome in paediatric infective endocarditis (IE) studies published since 2000.a

| Country | Number of episodes (patients) | Type of study | Setting | Years | Age | Heart diseaseStructural CHDRHD N (%) | NosocomialN (%) | Prosthetic materialN (%) | MicrobiologyBC + N (%)Germs N (%) | Embolisms: N (%)HF: N (%) | Surgical treatment(%) | Mortality rate (%) | RF pooroutcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain (present study) | 44 (41) | RS | MC | 2008−2020 | Median 103 mIQR: 37−150 m | 35 (80)34 (77)0 (0) | 19 (43) | 21 (48) | 41 (93)S. aureus 11 (25)CoNS 8 (18)S. viridans 6 (14)Fungal 3 (7) | 13 (30)Pulmonary 8 (18)Other 4 (9)CNS 3 (7) | 21 (48) | 4 (9) | Complicated IEProsthetic materialPCR >140 mg/l(MV) |

| Korea7 | 96 (89) | RS | SC | 2004−2019 | Median 9.5 yRange 2 d-19.8 y | 81 (84)81 (84)0 (0) | 33 (34) | 43% | 72 (75)S. aureus 24 (32)S. viridans 22 (29)CoNS 14 (19)Fungal 8 (11) | Pulmonary 14 (23)Non-pulmonary 14 (23)HF 23 (37) | 63 (67) | 7 (7.9) | ComplicationsS. aureus vs S. viridans(UV) |

| Australia8 | 51 (51) | RS | SC | 2009−2018 | Median 8.1 yIQR 2.7−12.8 y | 29 (57)25 (49)3 (6) | NS | 15 (29) | 46 (90)S. aureus 19 (37)Streptococcus spp. 15 (29)HACEK 7 (13)CoNS 2 (4) | 17 (33)Pulmonary 8 (16)CNS 5 (10) | 26 (51) | 1 (1.9) | Hospital stayDiagnosis timeEmbolisms(MV) |

| Brazil12 | 47 (45) | RS | SC | 2000−2018 | Mean 7.6 ySD 4.7 y | 44 (94)41 (87)3 (6) | 3 (6) | 19 (40) | 32 (68)S. viridans (19)S. aureus (15)CoNS (11) | Pulmonary 5 (11)Intracranial 3 (6)Other 4 (9)HF 7 (15) | 37 (79) | 7 (14.8) | NS |

| Belgium5 | 53 (53) | RS | SC | 2000−2017 | Mean 6.5 ySD 5.7 y | 46 (87)46 (87)0 (0) | 25 (47) | NS | 49 (92)S. viridans 17 (29)S. aureus 13 (22)CoNS 11 (19) | Pulmonary 6 (11)Systemic 5 (10)Intracranial 1 (2)HF: NS | 19 (36) | 7 (13) | NS |

| United Kingdom13 | 800 (736) | PCS | MC | 2008−2016 | <1 y: 75 (9%)1−15 y: 235 (32%)>15 y: 436 (59%) | 800 (100)b | NS | NS | 706 (88)Streptococci 280 (40)Staphylococci 230 (33) | NS | NS | 6.7% | DeathStaphylococcal infectionComplete AV canal defect (MV) |

| Norway14 | 36 (36) | RS | MC | 1994−2016 | Median 3.1 yIQR 0.7−9.9 y | 20 (67)20 (67)0 (0) | NS | NS | 30 (83)S. aureus 12 (33)S. viridans 8 (22) | 3 (8) | 13 (38) | 3 (8) | NS |

| Italy15 | 47 (47) | RS | SC | 2000−2015 | Median 9 yRange 2−17 y | 29 (62)29 (62)1 (2)c | NS | 12 (26) | 35 (74)S. viridans 12 (26)CoNS 8 (17)S. aureus 7 (15) | NS | 14 (30) | 3 (6.3) | NS |

| United States16 | 841 | RS | MC | 2003−2014 | Median 13 yIQR 9−15 y | 288/34288/34NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | 30 (3.6) | NS |

| Tunez17 | 73 (73) | RS | MC | 1997−2013 | Mean 12 yDS 4.8 y | 37 (51)18 (27)17 (23) | 31 (42)S. aureus 11 (15)CoNS 6 (8)Streptococcus spp. 6 (8) | Systemic 10 (14)CNS 9 (12)Pulmonary 2 (3) | 37 (51) | 10 (13.6) | DeathHFAKICNS involvement (MV) | ||

| Spain11 | 44 (44) | RS | SC | 1988-2013 | Median 6.8 yRange 3.5 m-17 y | 28 (63)28 (63)0 (0) | NS | 12 (27) | 43 (95)S. aureus 9 (21)S. viridans 9 (21)CoNS 7 (16)Fungal 8 (18) | Pulmonary 7 (16)Non-pulmonary 4 (9)HF 16 (36) | 13 (30) | 9 (20) | DeathComplicated IEHF (UV) |

| Cuba18 | 33 (33) | RS | SC | 2000−2012 | 0−4 y: 54%5−19 y: 46% | 22 (67)22 (67)0 (0) | 58% | NS | 25 (76)S. aureus 6 (24)S. viridans 5 (20)CoNS 8 (32) | Pulmonary 10 (22) Cerebral 5 (11)Renal 2 (4) | NS | NS | NS |

| New Zealand19 | 85 (82) | RS | MC | 1994−2012 | Median 7 yRange 0−15 y | 64 (75)51 (60)10 (12) | 35 (41) | NS | 75 (88)S. aureus 26 (31)S. pyogenes 7 (8) | NS | 39 (46) | 4 (5) | NS |

| Taiwan20 | 116 (112) | RS | SC | 1983−2011 | Mean 7.9 ySD 5.7 y | 86 (74)NSNS | 37 (32) | NS | 109 (94)Streptococcus spp. 55 (47)S. aureus 22 (19)Fungal 7 (6) | CNS 8 (7)Non-CNS 28 (24) | 34 (29) | 12 (10) | DeathHFVegetations (UV) |

| United States21 | 53 (47) | RS | SC | 1980−2011 | Median 12.3 yRange 0.01−18.9 y | 40 (75)40 (75)0 (0) | NS | NS | 47 (89)S. viridans 17 (36)S. aureus 12 (26)CoNS 2 (4) | 32% | 17 (32) | 2 (4) | NS |

| United States4 | 3,840 (3,840) | RS | MC | 2000−2010 | <1 y: 15%2−10 y: 28%11−19 y: 56% | 54%NSNS | NS | 8% | 70%S. aureus 37%Streptococcus spp. 39%S. viridans 26%CoNS 6% | NS | 9% | 2.8% | Hospital stayStaphylococcal infection (UV)DeathStaphylococcal infection(UV) |

| Spain10 | 45 | RS | SC | 1985−2009 | <1 y: 6 (13%)1−15 y 18 (40%)>15 y: 21 (47%) | 100%b | 38 (24) | 24 (53) | 43 (96)Streptococcus spp. 16 (35)S. aureus 7 (16)CoNS 7 (16)Fungal 6 (13) | Systemic 7 (16)Pulmonary 6 (14)CNS 4 (9)HF 10 (22) | 21 (47) | 12 (24) | DeathNosocomial infectionHF at diagnosis(MV) |

| Canada22 | 113 (113) | RS | SC | 1979−2008 | Median 7.6 yIQR 1.1−12.8 y | 95 (84)95 (84)0 (0) | 44 (39) | NS | 105 (93)S. aureus 43 (38)S. viridans 29 (26)CoNS 14 (12) | CNS 22 (19)Non-CNS 23 (20)VF 17 (15) | 40 (35) | 17 (15) | DeathBroad spectrum antibioticBiventricular vegetations (MV) |

| United States23 | 85 | RS | SC | 1992−2004 | Median 1.5 yRange 6 d-18.8 y | 72 (85)68 (80)1 (1) | 54 (64) | 19 (22) | 84 (99)Streptococcus spp. 26 (31)S. aureus 18 (21)CoNS 18 (21)Fungal 12 (14) | 19 (22.4)Pulmonary 9 (11)CNS 4 (5)Other 6 (7)HF 19 (22) | NS | 20 (23.5) | DeathNo RF identifiedComplicationsNosocomial(UV) |

| United States24 | 1,586 | RS | MC | 2000-2003 | Median: 16 y (UH)/10 y (NUH)IQR: 4−19 y (UH)/1−17 y (NUH) | 665 (42)535 (34)NS | NS | NS | NSS. aureus 57%S. viridans 24%CoNS 11% | NS | NS | 84 (5.3%) | NS |

| Argentina25 | 86 (86) | RS | SC | 1988−2000 | Median 7.6 yIQR 3.6−11.2 y | 66 (77)63 (73)3 (3) | NS | 20 (23) | 75 (87%)S. aureus 32 (37)S. viridans 14 (25)CoNS 4 (5) | 21 (24)CNS 17 (10)Pulmonary 2 (2)Other 2 (2)HF 26 (30) | 21 (24) | 11 (12.8) | ComplicationsS. aureusSurgical treatment (MV)DeathPrior antibiotic therapyPrevious surgery (MV) |

| United States23 | 62 | RS | SC | 1977-1992 | Median 8.2 yRange 1 m-19 y | 43 (69)40 (65)3 (5) | 24 (39) | NS | 58 (94)S. aureus 24 (39) Streptococcus spp. 14 (23)CoNS 7 (11) Fungal 6 (10) | 18 (29)Pulmonary 9 (14)CNS 9 (14)HF 10 (16) | NS | 13 (21) | NS |

| Spain9 | 23 | RS | SC | 1977−1985 | <2 y: 34.7%>2 y: 65.3% | 21 (91)20 (87)1 (4) | 8 (35) | 9 (39) | 22 (96)S. viridans 9 (39)S. aureus 8 (35)CoNS 2 (9) | NSHF 10 (43) | 8 (35) | 6 (26) | DeathNo RF identified |

| United States23 | 58 | RS | SC | 1930−1959 | Median 3 yRange 3 m-14 y | 58 (100)40 (69)18 (31) | NS | NS | 50 (86)Streptococcus spp. 40 (69)S. aureus 10 (17) | 38 (65)Pulmonary 13 (22)CNS 7 (4.2)Other 18 (31) | NS | 1930−1943 (86%)1944−1959 (34%) | NS |

CHD: congenital heart disease; AV canal: atrioventricular canal; RHD: rheumatic heart disease; SC: single centre; SD: standard deviation; CoNS: coagulase-negative staphylococci; PCS: prospective cohort study; RS: retrospective study; RF: risk factors; BC: blood culture; NUH: non-university hospital; UH: university hospital; HF: heart failure; AKI: acute kidney injury; MC: multicentre; MV: multivariate; NS: not specified; IQR: interquartile range; CNS: central nervous system; UV: univariate; VF: ventricular failure.

CHD are the main predisposing factor for IE in children, and it is estimated that children with CHD have a risk of developing IE 15–170 times higher than the general population.14 The prevalence of CHD in paediatric IE case series ranges from 27% to 100%; the wide discrepancy may be explained by differences in data collection protocols, periods, reference populations, and types of hospitals.4,5,7–25 In this case series, CHD were a pre-existing risk factor in 77% of the IE cases, with VSD being the most commonly identified acyanotic and TA and TOF the most common cyanotic CHD, all consistent with the findings reported in contemporary IE series.5,7,8 TOF (22.8%), VSD (19.6%) and bicuspid aortic valve (10.7%) were the most prevalent CHD in a recent prospective study conducted in the United Kingdom, which included 800 episodes of IE in 736 patients with a history of CHD, 300 of whom were <16 years old.13 None of the patients had rheumatic valve involvement; this was an issue in historical studies of IE and, more recently, in the aboriginal population and less developed countries.8,9,12,17,19,23,25

In this study, CVC and immune system dysfunction, predisposing factors commonly described in paediatric IE series, occurred in 20% and 16% of IE cases, respectively.7,8,23,24 Episodes of IE with the presence of CVC as a predisposing factor occurred in 89% with involvement of the right chambers and were responsible for the three episodes of fungal infection, findings consistent with the characteristics described for IE in patients with CVC.26

Slightly less than half (48%) of the IE episodes in this patient cohort were related to the presence of prosthetic material, a higher rate than in most reports of paediatric IE, where the range is from 8% to 53%. In the cases described, eight patients had a Contegra bovine jugular vein valve conduit, with higher incidence rates of IE than cryopreserved homografts.27

IE episodes in the prosthetic material group were associated with higher rates of CHD and organ dysfunction. They were also associated with three and four times higher rates, respectively, of AKI and LD than in the group without prosthetic material. Although the difference was not statistically significant, possibly due to the low frequency of these complications, it was considered relevant from the clinical point of view. These findings could be related to the prosthetic material and the fact that they generally occur in more complex heart diseases. Moreover, multivariate analysis showed the presence of prosthetic material to be an independent predictor of complicated IE. This finding was not unexpected, as prosthetic material is considered a predisposing factor in children with IE for serious complications which can require early surgery.2

In this series, the median duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis was nine days, but there were cases where diagnosis was significantly delayed due to relatively benign and nonspecific initial presentation, and in other episodes early diagnosis was hampered by atypical symptoms, which can obscure the diagnosis, as in the three children with acalculous cholecystitis. This is a complication only very rarely reported in IE, generally in the context of S. aureus infection, although it is probably underdiagnosed.28 Early diagnosis of paediatric IE can also be complicated by the differences in presentation depending on the child's age and by the lower sensitivity of echocardiography in the group of patients with prosthetic material.1,2,29

Fever was the most common symptom. This can initially be very variable, from seeming relatively benign with non-specific symptoms to severe symptoms of sepsis and heart failure, observed in 23% of the episodes.2 Skin lesions characteristic of IE were detected in five (11%) episodes, the proportion being similar to that reported in other paediatric IE series and lower than that reported in adult patients.2,8,11,15,19

S. aureus, followed by CoNS and S. viridans were the most commonly isolated microorganisms in the patients in our study. These are the most important microorganisms in the aetiology of IE in children, with differences in their relative frequencies (Table 6).4,7–25 In a systematic literature review, S. aureus was the most prevalent microorganism, as it was in our study and other more recent series.7,8,14,19,30 However, in other recent series from developed countries, S. viridans plays a major role as a causal agent of paediatric IE.5,15 The high rates of S. aureus can be a cause for concern. It was associated with a higher risk of complications and death in IE studies with more cases and adult patients.6,13,25We did not find this in our case series, but the discrepancy could be related to our study's lack of statistical power.

The rate of thromboembolic complications was 30%, comparable to that of most paediatric IE studies, with a range of 8%–46% (Table 6).4,7–25 It is possible that greater use of advanced multimodal imaging techniques could have increased the detection of relatively silent complications from a clinical point of view. In the series described, 18F-FDG-PET/CT was used in nine episodes. This imaging technique is a potentially useful and reliable tool in the IE diagnostic algorithm for the identification of septic embolisms and evaluation of prosthetic material infections when echocardiography is inconclusive.29 However, information on the role of this and other advanced imaging techniques in IE is insufficient to make general recommendations.

The rate of those requiring surgery reached 48%, and the mortality rate was 9%, similar to those described in the paediatric IE series.4,5,7–25 CRP values >140 mg/l and prosthetic material were independent predictors of complicated IE, which may help in the early identification of patients who possibly need surgery. In this regard, it was interesting that early or late diagnosis was not associated with the development of complicated IE. Other variables independently associated with complications and the possible need for surgery and with death in the different paediatric IE studies are shown in Table 6.4,7–25

This study has limitations inherent to retrospective studies, with potential selection and information biases. Moreover, the limited number of patients may have affected the statistical power and the likelihood of making type II errors.

In summary, our findings underline the high levels of morbidity and the complexity of managing paediatric IE. The information generated by this study could help better identify the epidemiological and clinical profiles of paediatric patients with IE and its complicated forms. Lastly, to help resolve the areas of uncertainty, prospective multicentre studies should be carried out with larger samples of patients to optimise the diagnostic and therapeutic management of this serious condition.

Conflicts of interestNone of the authors have any conflicts of interest.

We would like to acknowledge the members of the Red de Endocarditis Pediátrica Andaluza (REPA) [Andalusian Paediatric Endocarditis Network] Dolores Falcón Neyra, Olaf Werner Neth, Juan Luis Santos Pérez and Laura Martín Pedraz.