Malignant or invasive external otitis (MEO) is a rare disease. It is mainly caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and typically affects elderly patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) or other immunocompromised individuals.1

Aspergillus MEO frequently involves necrosis of the epithelium and subepithelial tissue of the external auditory canal, bone erosion, and perforation of the tympanic membrane.2

An 80-year-old patient with a history of high blood pressure and DM was referred to the ENT department for persistent pain in his left ear for 4 months. At the initial evaluation, only medial otorrhea was found and antibiotic drops were prescribed. The ear pain persisted and extended to the left side of the patient's face and left buccal mucosa. He was treated with carbamazepine and tramadol, with no response. At the next visit, he presented with edema of the external auditory canal, left hearing loss, and a tumefaction at the left temporomandibular joint with normal cranial nerve examination results.

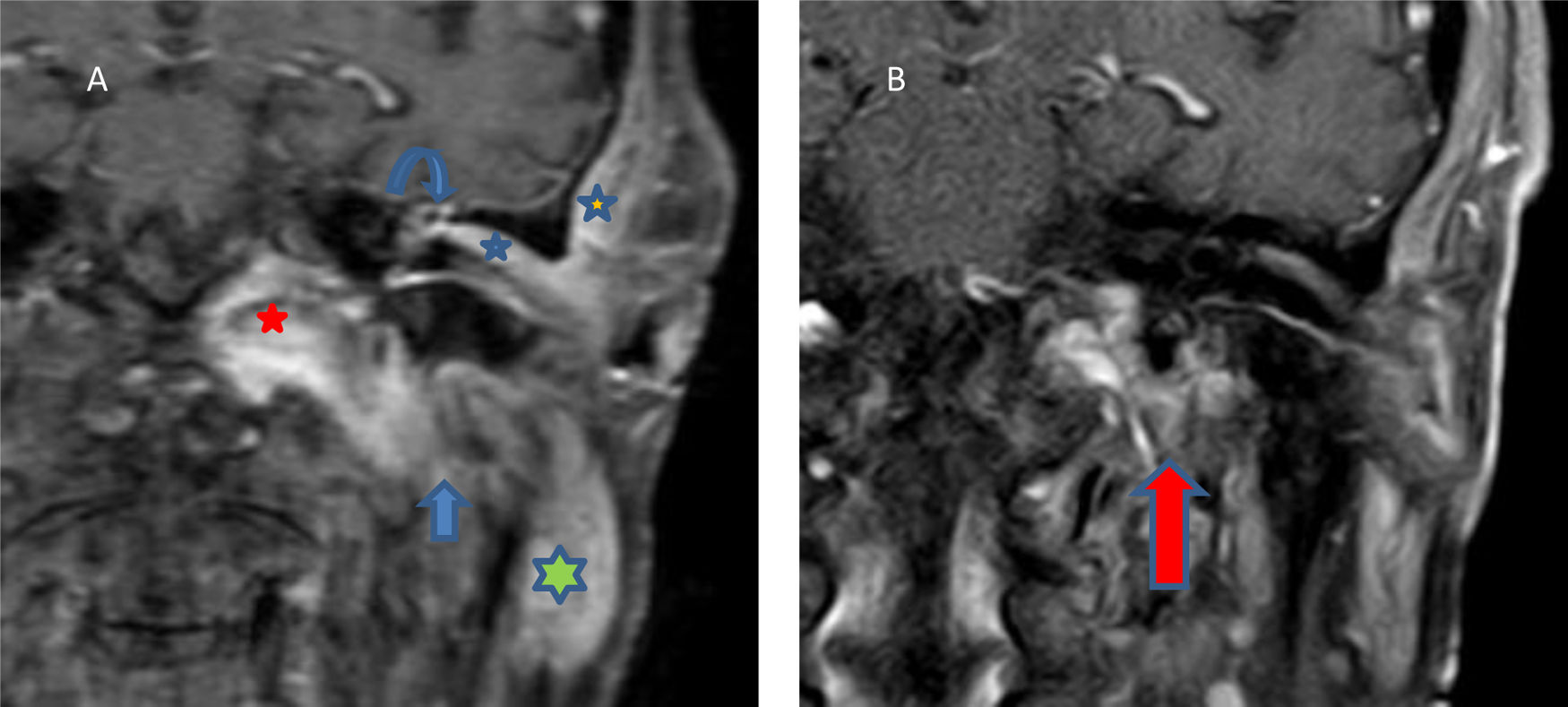

A cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed, with images suggestive of left MEO, inflammatory changes in the middle ear and deep cervical spaces, and a small abscess in the chewing space, osteomyelitis in the left clivus and left occipital condyle (Fig. 1A).

(A) Coronal T1 sequence, gadolinium. Thickening of the left external auditory canal (blue star) and soft tissues (orange star), parotid gland (green star), temporomandibular joint (straight arrow), occipital condyle (red star) and middle ear (curved arrow)]. (B) Similar section after 18m. Clear improvement, with disappearance of the occupation of the middle ear and decrease in the volume of the tissues originally affected. Unspecific enhancement at the jugular foramen (red arrow).

Treatment with intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam and vancomycin was prescribed. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the skull base showed that soft tissue occupied the external auditory canal and middle ear, and it also showed erosion and dehiscence of the tegmen timpani, mastoid sclerosis, and bone erosion in the left jugular foramen, front and lateral wall of occipital condyle, and carotid duct.

A biopsy of the external auditory canal was conducted. Histologically, granulation tissue by non-specific inflammation was observed. A. flavus were found in culture, with no malignancy findings. A. flavus CMI to voriconazole was 0.25μg/mL. Antibiotic treatment was simplified to ciprofloxacin and voriconazole, which was well tolerated. After 2 weeks of hospitalization the patient was discharged with oral voriconazole. At the follow-up visits, he remained afebrile, with complete resolution of the ear pain, but with a mild temporal headache. Treatment with voricozale monotherapy was continued.

A myringotomy and transtympanic drainage in left ear were performed, obtaining retrotympanic mucus. After the procedure, the patient's hearing loss was reversed, and there was complete resolution of the temporal headache. The patient recovered after 6 months of treatment with voriconazole and without the need for surgical debridement. The study was completed 18 months after diagnosis using MRI (Fig. 1B), which showed that the middle ear was no longer occupied and that there was no enhancement of the originally affected tissues.

The usual clinical course of fungal MEO includes painful inflammation of the external ear canal, associated with purulent otorrhea and granulation polyps. Otalgia is the presenting symptom in 75% of cases and purulent otorrhea in 50–80%.3 Cranial nerve neuropathies are also seen, with particular involvement of the facial nerve.

Histologically, granulation tissue is characterized by non-specific inflammation with inflammatory cell infiltration and hyperplasia of squamous epithelium.3

It can be confused with bacterial MEO that is caused by P. aeruginosa, and as a result, the diagnosis of fungal disease is often delayed. Suspicion of fungal MEO should be raised if recurrence or no response to appropriate antimicrobial therapy.3

However, Aspergillus is also frequently isolated from external auditory canal smears and diagnosis of fungal MEO should be based on culture biopsy or histopathologic confirmation.2,3

Aspergillus MEO requires long-term antifungal therapy in association with appropriate management of the underlying condition, which is usually DM. In addition, prompt surgical debridement consisting of radical mastoidectomy is required in many cases.1–3

Prolonged voriconazole use is an effective treatment for Aspergillus MEO. However, surgical debridement is still necessary for refractory and invasive Aspergillus MEO.4

In another series of 14 patients with MEO that was caused by Aspergillus spp, only two patients relapsed after 4 and 8-week treatments with voriconazole.2

There is no consensus on the antifungal treatment duration; patients usually receive 6–8 weeks of antifungal therapy or more if clinical examination or imaging follow-up supports extending the treatment.4,5

![(A) Coronal T1 sequence, gadolinium. Thickening of the left external auditory canal (blue star) and soft tissues (orange star), parotid gland (green star), temporomandibular joint (straight arrow), occipital condyle (red star) and middle ear (curved arrow)]. (B) Similar section after 18m. Clear improvement, with disappearance of the occupation of the middle ear and decrease in the volume of the tissues originally affected. Unspecific enhancement at the jugular foramen (red arrow). (A) Coronal T1 sequence, gadolinium. Thickening of the left external auditory canal (blue star) and soft tissues (orange star), parotid gland (green star), temporomandibular joint (straight arrow), occipital condyle (red star) and middle ear (curved arrow)]. (B) Similar section after 18m. Clear improvement, with disappearance of the occupation of the middle ear and decrease in the volume of the tissues originally affected. Unspecific enhancement at the jugular foramen (red arrow).](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/2529993X/0000003900000007/v1_202108030541/S2529993X21001350/v1_202108030541/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)