Cervical lymphadenitis is the most common nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) infection in immunocompetent children, mainly in those under 5 years. For many years Mycobacterium lentiflavum (M. lentiflavum) has been considered a rare NTM causing lymphadenitis.

MethodsA restrospective study was performed in pediatric patients with microbiologically confirmed NTM cervical lymphadenitis at the Niño Jesús Hospital in Madrid during 2009–2016.

ResultsDuring the period studied, 28 cases of cervical lymphadenitis were recorded. In 23 (82.14%) and in 5 (17.85%) cases, M. lentiflavum and Mycobacterium avium were isolated, respectively. In those patients infected with M. lentiflavum, the most frequent location was sub-maxilar (43.47%); 15 (65.21%) were boys, global median age was 30.8 months and all cases showed a satisfactory evolution.

ConclusionWe propose that M. lentiflavum should be considered an important emergent pathogen cause of cervical lymphadenitis in the pediatric population.

La linfadenitis cervical es la infección más frecuente por micobacterias no tuberculosas (MNT) en niños inmunocompetentes, principalmente menores de 5 años. Durante años se ha considerado a Mycobacterium lentiflavum (M. lentiflavum) una inusual MNT causante de esta patología.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio retrospectivo, observacional desde 2009 a 2016, que incluyó a pacientes pediátricos del Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús de Madrid, diagnosticados clínicamente y microbiológicamente de linfadenitis cervical por MNT.

ResultadosEn el periodo estudiado se registraron 28 casos de linfadenitis cervical. En 23 (82,14%) pacientes se aisló M. lentiflavum y en 5 (17,85%), Mycobacterium avium. De los 23 pacientes con infección por M. lentiflavum, la localización más frecuente fue la submandibular (43,47%), 15 (65,21%) fueron niños, la media de edad global fue de 30,8 meses y todos los casos evolucionaron satisfactoriamente.

ConclusiónM. lentiflavum debe ser considerado como un importante patógeno emergente causante de linfadenitis cervical en población pediátrica.

Cervical lymphadenitis is the most common manifestation of infection with non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) in immunocompetent children, mainly under 5 years of age.1–3 NTM are ubiquitous bacteria with a global distribution that are isolated from large numbers of sources such as soil, natural water and the water supply, milk, dust, and birds and other animals.3,4 Cervical lymphadenitis, or inflammation of the lymph nodes, due to NTM occurs following ingestion or inhalation of contaminated products. NTM account for 10–20% of all cases of cervical lymphadenitis in preschool children.5 The most common clinical finding is the appearance of a painless mass (in most cases there is only one) in the submandibular, anterior cervical or preauricular region.

In developed countries such as the United States and much of Europe, Mycobacterium avium (M. avium) complex (MAC) is the most common responsible agent (70–80%).6 The second most common responsible agent depends on the country. It is Mycobacterium malmoense in Sweden and the United Kingdom and Mycobacterium haemophilum in the Netherlands and Israel.7 The first 2 case reports of lymphadenitis caused by Mycobacterium lentiflavum (M. lentiflavum) were reported in 1997.8 For many years, M. lentiflavum was considered unusual as a pathogen causing cervical lymphadenitis. However, a sharp increase in the number of cases caused by this NTM detected in Spain and Australia in recent years has made it the second most common cause of lymphadenitis in children, just behind MAC.9,10 Based on these data, M. lentiflavum can be considered an emerging pathogen, responsible for cervical lymphadenitis.

The objective of this study was to report the cases of cervical lymphadenitis due to NTM in recent years in the paediatric population of our Health Area, with a focus on the epidemiology, clinical characteristics and treatment of cases caused by M. lentiflavum.

MethodsAn observational, retrospective study conducted from 2009 to 2016 enrolled paediatric patients from Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús in Madrid who had been clinically diagnosed with lymphadenitis and from whom an NTM isolate had been obtained. Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús is a public institution of the Madrid Health Service that provides specialised healthcare services to paediatric patients (0–18 years of age) from the Autonomous Community of Madrid and all autonomous communities in accordance with current regulations and legislation. The Servolab Laboratory Information System (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA, United States) was used as a database.

The patients’ medical records were reviewed to collect their demographic and clinical data as well as information on their treatment and clinical course. The conduct of the study was approved by the Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús Independent Ethics Committee (internal code R-0053/16). Mycobacterial diagnosis was performed in the Microbiology Department at Hospital Universitario de la Princesa in Madrid.

Samples for microbiology were obtained by means of fine needle aspiration biopsy or lesion biopsy. Direct bacilloscopy was done through auramine staining of samples, and mycobacterial culture was done though incubation of samples in MGIT liquid medium (Becton-Dickinson Diagnostic Systems, Sparks, MD, United States) for up to 8 weeks in the automated BACTEC MGIT 960 system (Becton-Dickinson Diagnostic Systems, Sparks, MD, United States). Once the system detected a positive sample, that sample underwent Ziehl–Neelsen staining and culture in Coletsos solid medium (bioMérieux, Lyon, France). Isolates were identified using the GenoType CM/AS technique (HAIN Lifescience, Nehren, Germany) and, as of 2015, the MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry technique (Bruker-Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). Identification was deemed acceptable when a score was greater than or equal to 1.8. Isolates that could not be identified at our laboratory were sent to the Mycobacteriology Department of the Spanish National Microbiology Centre (Instituto de Salud Carlos III) and identified using polymerase chain reaction followed by enzymatic restriction of the gene that encodes for heat shock protein 65 (hsp65).

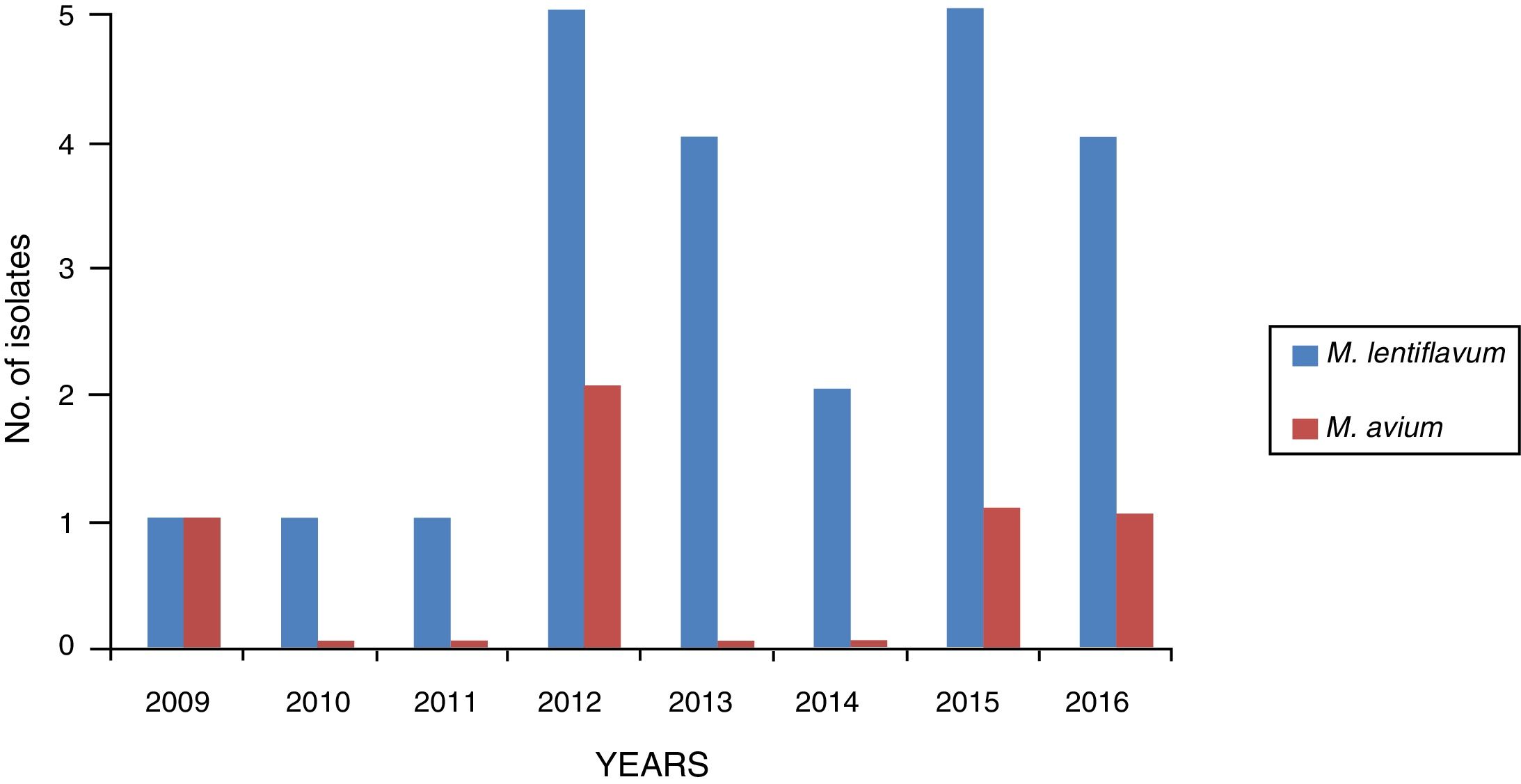

ResultsA total of 28 cases of NTM were recorded from samples from patients with lymphadenitis: 23 caused by M. lentiflavum (82.14%) and 5 caused by M. avium (17.85%). Of the 28 strains, 2 were sent for identification to the Spanish National Microbiology Centre (CNM) and ultimately identified as M. lentiflavum. Fig. 1 shows the distribution of the isolates in the 8 years studied.

Among the 23 paediatric patients with lymphadenitis due to M. lentiflavum, 8 were girls and 15 were boys, and their mean age was 30.8 months (range: 14–61 months). Just 3 of the patients had a significant medical history or disease: Duchenne muscular dystrophy, neonatal meningitis and mild microcephaly. None of the patients had any immunodeficiencies and all normally resided in the Autonomous Community of Madrid.

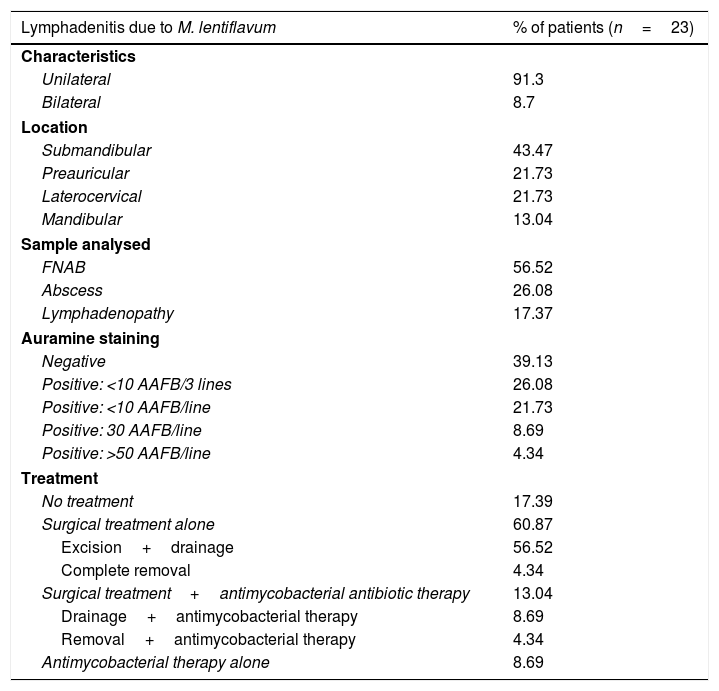

Table 1 indicates the clinical characteristics and treatment of the patients studied. Regarding treatment, 5 (21.74%) of the patients received antimycobacterial therapy, and 3 of them also required surgical treatment: 2 needed drainage and excision and 1 needed complete removal of their lymphadenopathy. The antimycobacterial therapy for the latter consisted of clarithromycin, rifabutin and ethambutol. One of the 2 patients who required drainage received clarithromycin and rifampicin. The other received azithromycin and ethambutol. The 2 patients whose treatment was antimycobacterial alone received clarithromycin.

Clinical characteristics and treatment of the 23 patients who presented lymphadenitis due to M. lentiflavum in our cohort (2009–2016).

| Lymphadenitis due to M. lentiflavum | % of patients (n=23) |

|---|---|

| Characteristics | |

| Unilateral | 91.3 |

| Bilateral | 8.7 |

| Location | |

| Submandibular | 43.47 |

| Preauricular | 21.73 |

| Laterocervical | 21.73 |

| Mandibular | 13.04 |

| Sample analysed | |

| FNAB | 56.52 |

| Abscess | 26.08 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 17.37 |

| Auramine staining | |

| Negative | 39.13 |

| Positive: <10 AAFB/3 lines | 26.08 |

| Positive: <10 AAFB/line | 21.73 |

| Positive: 30 AAFB/line | 8.69 |

| Positive: >50 AAFB/line | 4.34 |

| Treatment | |

| No treatment | 17.39 |

| Surgical treatment alone | 60.87 |

| Excision+drainage | 56.52 |

| Complete removal | 4.34 |

| Surgical treatment+antimycobacterial antibiotic therapy | 13.04 |

| Drainage+antimycobacterial therapy | 8.69 |

| Removal+antimycobacterial therapy | 4.34 |

| Antimycobacterial therapy alone | 8.69 |

AAFB: acid alcohol fast bacilli; FNAB: fine needle aspiration biopsy.

The clinical courses of the patients were studied at their surgery visits. The review of the medical records did not contribute any case of sequelae or relapse.

DiscussionTo our knowledge, this study represents the most extensive case series of lymphadenitis caused by M. lentiflavum in children, with a total of 23 cases. For years, as reflected in the published literature, MAC was the main NTM responsible for this disease in developed countries and isolation of M. lentiflavum was very unusual. However, 2 studies with case series in which this NTM was the second most frequently isolated NTM have recently been published. One of them was a national multi-centre study in Australia. In this study, M. lentiflavum was the second most common NTM behind MAC.10 The other was a retrospective multi-centre study conducted in Spain and involving 6 hospitals in Madrid from 2000 to 2010. In this study, M. lentiflavum was the most frequently isolated NTM (37.7%) after MAC (48.8%).9

Regarding the clinical characteristics of lymphadenopathy in our series, in the vast majority of cases this was unilateral (91.3%) with a submandibular location (43.47%). Both characteristics corresponded to those found in other similar studies with respect to lymphadenopathy caused by M. lentiflavum as well as lymphadenopathy caused by MAC.3,9,11 Our study found a higher rate of samples with positive staining (60.87% versus <35%). One possible reason for this was the amount of sample processed, since in our case a swab of sample was also received, prepared at the time of sampling and later stained in our laboratory. Another possible reason was the type of staining used (auramine versus Ziehl–Neelsen as in other studies).3,9 Regarding treatment, 17.39% of our patients experienced spontaneous resolution of lymphadenopathy. Most (60.87%) received surgical treatment alone with no need for antibiotics. The most common option was partial excision and drainage. This was another way in which our series differed from one of the other published series. In that series, 64.7% of patients received a combined treatment of surgery and antimicrobials and the most common option was complete removal.9 This difference might have been due to the criteria set out in the different medical/surgical guidelines at each hospital.

The increase in the number of M. lentiflavum isolates in recent years may be attributed to different factors. On the one hand, ever-increasing numbers of laboratories are using automated liquid media to isolate mycobacteria, resulting in increased detection of these microorganisms. Various studies have attested to this.12,13 The increase in the disease examined in this study could have been due to the BCG vaccine's lack of a possible cross-protection effect, as mentioned above.13 Finally, the increase in this species in particular could be explained from the point of view of the use of new molecular diagnostic techniques in clinical laboratories. M. lentiflavum is difficult to distinguish from other NTM using phenotypic and biochemical methods; therefore, in the past, it could have been erroneously identified as MAC or another NTM.9,14 Molecular techniques and, more recently, mass spectrometry are vital tools for properly identifying NTM on a species level and may play an essential role in this regard.15

This study did have some limitations. One was that the series referred only to cases with a positive culture. It would be very useful to collect cases with a strong suspicion of NTM with no evidence of mycobacteria and to compare changes over time in those cases (molecular biology techniques might play a significant role in such an endeavour). In addition, the group of patients studied did not present any sort of immunodeficiency. Comparing our results to results for immunosuppressed patients would contribute to the knowledge of the epidemiology of M. lentiflavum.

In order for these findings to be firmly grounded, we believe that more extensive international studies must be conducted to determine whether the increase in the number of cases in countries such as Spain and Australia was due to local ecological factors, since some publications have pointed to drinking water as the source of infection with this mycobacterium.16–18

In summary, based on other published studies and on our series, we believe that M. lentiflavum should be considered an important NTM causing lymphadenitis in children.

AuthorshipAll the authors declare that they have read and approved the manuscript and that the requirements for authorship have been met.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have not received any sort of funding to prepare this document and that they have no conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank Dr María Soledad Jiménez from the Mycobacteriology Department at the Spanish National Microbiology Centre (Instituto de Salud Carlos III) for her assistance.

Please cite this article as: Miqueleiz-Zapatero A, Olalla-Peralta CS, Guerrero-Torres MD, Cardeñoso-Domingo L, Hernández-Milán B, Domingo-García D. Mycobacterium lentiflavum como causa principal de linfadenitis en población pediátrica. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2018;36:640–643.