The deletion in the CCR5 gene (CCR5-Δ32), the HLA-B*27:05, and polymorphisms rs2395029 and rs9264942 have been associated with slower progression of HIV-1.

MethodsAn analysis was performed on 408 patients on follow-up. The analysis of viral load, CD4+ T lymphocytes and other clinical variables since the diagnosis of the infection were collected.

ResultsThe prevalence of the genetic markers rs9264942, CCR5wt/Δ32, rs2395029, HLA-B*27:05 was 17.9%, 11.5%, 7.6%, and 6.4%, respectively. Of all the patients, 354 were classified as progressors and 46 as long-term non-progressors (LTNPs). Except for the HLA-B*27:05 allele, other genetic markers were associated with slower progression: CCR5wt/Δ32 (p=0.011) and SNPs rs2395029 and rs9264942 (p<0.0001), as well as their association (p<0.0001).

ConclusionThe prevalence of the HLA-B*57:01 allele was higher than described nationally. No association could be found between the HLA-B*27:05 allele and the presence of slower disease progression.

La deleción en el gen CCR5 (CCR5-Δ32), el haplotipo HLA-B*27:05 y los polimorfismos rs2395029 y rs9264942 han sido relacionados con la lenta progresión de la infección por VIH-1.

MétodosAnalizamos a 408 pacientes en seguimiento. El análisis de la carga viral, linfocitos T CD4+ y demás variables clínicas fueron recogidas desde el diagnóstico.

ResultadosLa prevalencia de los marcadores genéticos rs9264942, CCR5wt/Δ32, rs2395029 y alelo HLA-B*27:05 fue del 17,9, del 11,5, del 7,6 y del 6,4%, respectivamente. Del total de los pacientes, 354 fueron clasificados como progresores y 46 como no progresores a largo plazo (LTNP). Exceptuando el alelo HLA-B*27:05, los demás marcadores genéticos se relacionaron con la lenta progresión: CCR5wt/Δ32 (p=0,011) y los SNP rs2395029 y rs9264942 (p<0,0001), así como su asociación (p<0,0001).

ConclusiónLa frecuencia hallada del alelo HLA-B*57:01 fue mayor a lo publicado a nivel nacional. Con respecto al alelo HLA-B*27:05, no hemos podido relacionar su presencia con la lenta progresión.

Most patients infected with HIV-1 (80–85%) progress to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in the absence of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) within a period of between 8 and 10 years (chronic progressors), due to a progressive drop in the number of T CD4+ lymphocytes.1,2

Based on the rate of disease progression, a subgroup of patients (5–15%) known as long-term non-progressors (LTNP) has been identified, whose progression occurs more slowly, characterised by remaining clinically asymptomatic and/or immunologically stable, with a normal T CD4+ lymphocyte count for at least 8 years.3,4

Thanks to viral load determinations, it has been proven that LTNPs possess phenotypic characteristics that can be divided into three subgroups: “viraemic non-controllers” (LTNP-NC), “viraemic controllers” (LTNP-VC), and “elite controllers” (LTNP-EC). The latter account for a percentage (<1%) of all patients and are characterised by maintaining an undetectable plasma viral load without HAART.4

This slow progression of HIV-1 infection depends on the interactions between the virus, the host and the environment.5 The host's genetic factors include genetic polymorphisms affecting the virus’ ability to penetrate the cell, as occurs when 32pb is deleted in the gene coding for the CCRW co-receptor (CCR5-Δ32), and the haplotypes associated with the human leucocyte antigen (HLA) presentation region, such as the HLA-B*57:01 allele (rs2395029 SNP), the HLA-B*27:05 allele, and homozygosis C/C of the rs9264942 SNP of HLA-C, which regulate the specific immune response to infection in the host.6–9

The study objective was to analyse the epidemiological, clinical and analytical characteristics of the patients infected with HIV-1 monitored at our medical centre, to estimate the prevalence of these genetic markers and to determine their relation with infection progression.

Materials and methodsThe patients enrolled belong to the HIV+outpatient clinic of the Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo [Vigo University Medical Complex] (CHUVI). The study was conducted under the approval of the CHUVI Independent Ethics Committee and in adherence to the Declaration of Helsinki.10

Out of all the patients being monitored in January 2007 (n=917), 408 patients were included who attended an appointment during the enrolment period (January 2007–January 2009) and who attended at least 2–4 visits per year since their diagnosis until the end of the study (January 2013).

The T CD4+ count was done using flow cytometry (FACScalibur, Becton Dickinson, USA). The plasma viral load (copies of HIV-1/ml) was quantified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR), COBAS® AmpliPrep/COBAS® TaqMan® HIV-1 Test, version 2.0 48 test IVD (Roche, Switzerland). The DNA was extracted from peripheral blood using the FlexiGene DNA kit (QIAGEN, Germany).

Deletions (CCR5-Δ32) were detected using the protocol described by Huang et al.11 The primers described by Sayer et al. were used for PCR amplification of the HLA-B*27:05 allele.12 The technique described and validated by Martin et al. was used to determine the HLA-B*57:01 allele.13 The primers described by Van Manen et al. were used to amplify the rs9264942 SNP.9

Given the absence of a standard definition to classify patients based on HIV-1 infection progression, we have adopted the definitions described by Casado et al.14 using the progression criteria described by Fellay et al.8

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

ResultsIn our cohort, the most prevalent genetic marker was the homozygous rs9264942 SNP, with 17.9%, followed by deletion (CCR5-Δ32), with a prevalence of 11.5%, heterozygous in all cases, while the prevalence for the HLA-B*57:01 allele (rs2395029 SNP) was 7.6%, and 6.4% for the HLA-B*27:05 allele.

Of all the patients included in this study (n=408), 4 were lost to follow-up and a further 4 did not meet the criteria “follow-up time necessary to be able to classify the patients based on HIV-1 infection progression”, which needed to be ≥8 years. Of these 400 patients, 46 (11.5%) were categorised as LTNP, while the rest (n=354; 88.5%) were categorised as progressors.

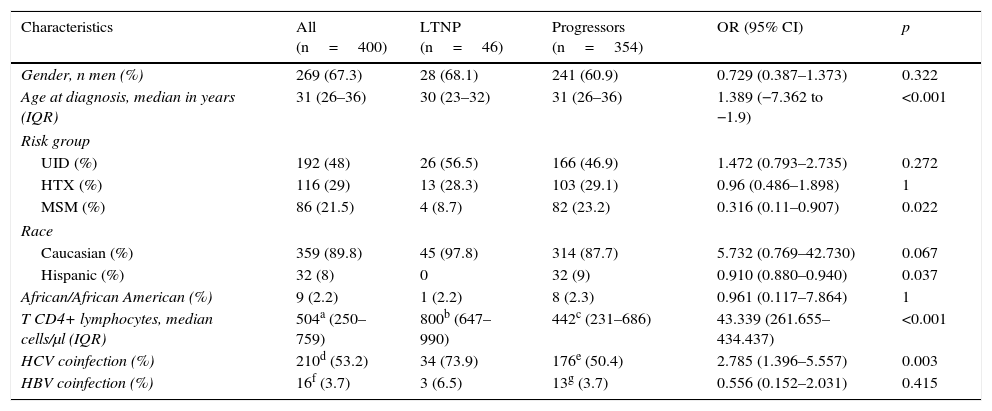

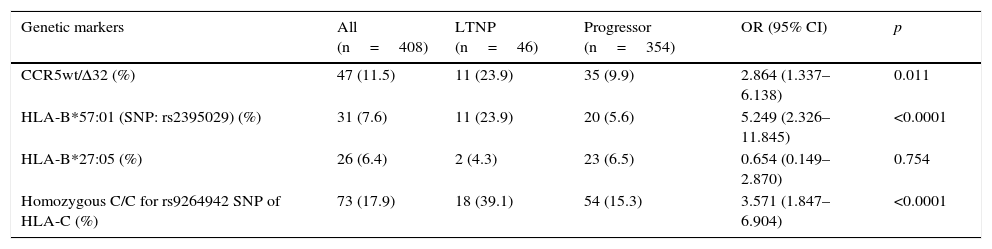

The most relevant epidemiological, clinical and analytical characteristics of the 2 patient subgroups are summarised in Table 1. The prevalence and distribution of the genetic markers based on infection progression are collected in Table 2, where it can be observed that all the markers studied, except the HLA-B*27:05 allele, presented statistically significant differences.

Epidemiological, clinical and analytical characteristics of the study population at HIV-1 infection diagnosis, classified in accordance with progression.

| Characteristics | All (n=400) | LTNP (n=46) | Progressors (n=354) | OR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n men (%) | 269 (67.3) | 28 (68.1) | 241 (60.9) | 0.729 (0.387–1.373) | 0.322 |

| Age at diagnosis, median in years (IQR) | 31 (26–36) | 30 (23–32) | 31 (26–36) | 1.389 (−7.362 to −1.9) | <0.001 |

| Risk group | |||||

| UID (%) | 192 (48) | 26 (56.5) | 166 (46.9) | 1.472 (0.793–2.735) | 0.272 |

| HTX (%) | 116 (29) | 13 (28.3) | 103 (29.1) | 0.96 (0.486–1.898) | 1 |

| MSM (%) | 86 (21.5) | 4 (8.7) | 82 (23.2) | 0.316 (0.11–0.907) | 0.022 |

| Race | |||||

| Caucasian (%) | 359 (89.8) | 45 (97.8) | 314 (87.7) | 5.732 (0.769–42.730) | 0.067 |

| Hispanic (%) | 32 (8) | 0 | 32 (9) | 0.910 (0.880–0.940) | 0.037 |

| African/African American (%) | 9 (2.2) | 1 (2.2) | 8 (2.3) | 0.961 (0.117–7.864) | 1 |

| T CD4+ lymphocytes, median cells/μl (IQR) | 504a (250–759) | 800b (647–990) | 442c (231–686) | 43.339 (261.655–434.437) | <0.001 |

| HCV coinfection (%) | 210d (53.2) | 34 (73.9) | 176e (50.4) | 2.785 (1.396–5.557) | 0.003 |

| HBV coinfection (%) | 16f (3.7) | 3 (6.5) | 13g (3.7) | 0.556 (0.152–2.031) | 0.415 |

HTX, heterosexual; IQR, interquartile range; LTNP, long-term non-progressors; MSM, men who have sex with men; UID, users of injected drugs.

Data obtained from:

Prevalence of the genetic markers in the study population, distributed based on infection progression.

| Genetic markers | All (n=408) | LTNP (n=46) | Progressor (n=354) | OR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCR5wt/Δ32 (%) | 47 (11.5) | 11 (23.9) | 35 (9.9) | 2.864 (1.337–6.138) | 0.011 |

| HLA-B*57:01 (SNP: rs2395029) (%) | 31 (7.6) | 11 (23.9) | 20 (5.6) | 5.249 (2.326–11.845) | <0.0001 |

| HLA-B*27:05 (%) | 26 (6.4) | 2 (4.3) | 23 (6.5) | 0.654 (0.149–2.870) | 0.754 |

| Homozygous C/C for rs9264942 SNP of HLA-C (%) | 73 (17.9) | 18 (39.1) | 54 (15.3) | 3.571 (1.847–6.904) | <0.0001 |

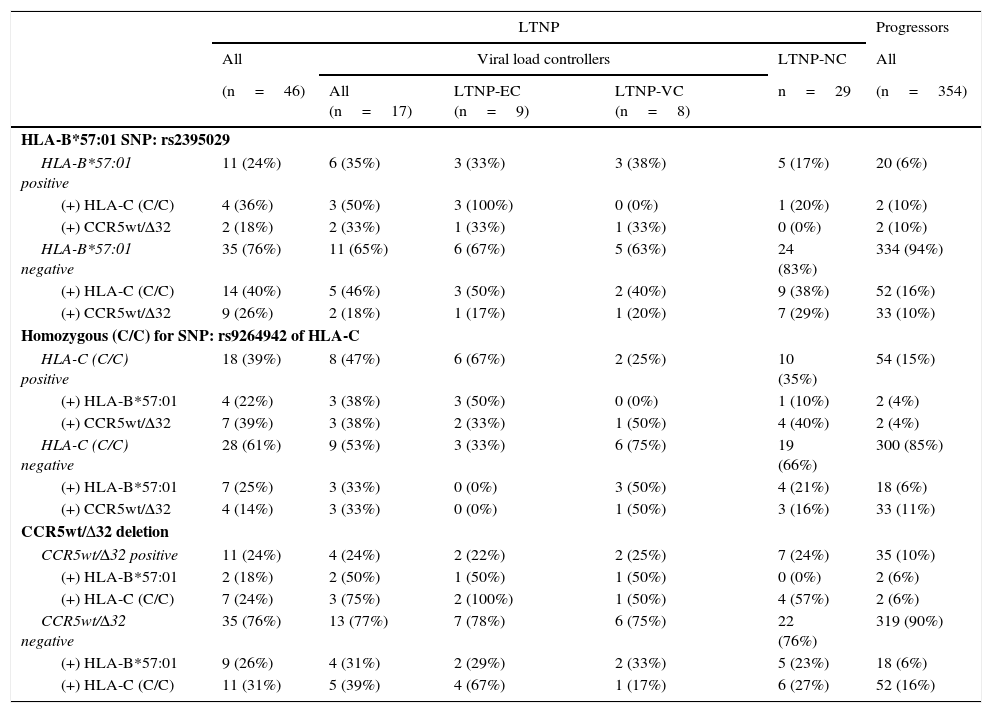

In the association study between the different genetic variants and their correlation with slow progression (Table 3), it was observed that 24% of the patients classified as LTNP (n=11) presented some type of association, versus 1.7% of the patients classified as progressors (n=6), obtaining significant differences (p<0.0001; OR=18.229; 95% CI: 6.335–52.283).

Prevalence and association of the genetic markers correlated with slow progression, distributed in the different patient subgroups categorised in accordance with HIV-1 infection progression.

| LTNP | Progressors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Viral load controllers | LTNP-NC | All | |||

| (n=46) | All (n=17) | LTNP-EC (n=9) | LTNP-VC (n=8) | n=29 | (n=354) | |

| HLA-B*57:01 SNP: rs2395029 | ||||||

| HLA-B*57:01 positive | 11 (24%) | 6 (35%) | 3 (33%) | 3 (38%) | 5 (17%) | 20 (6%) |

| (+) HLA-C (C/C) | 4 (36%) | 3 (50%) | 3 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (20%) | 2 (10%) |

| (+) CCR5wt/Δ32 | 2 (18%) | 2 (33%) | 1 (33%) | 1 (33%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (10%) |

| HLA-B*57:01 negative | 35 (76%) | 11 (65%) | 6 (67%) | 5 (63%) | 24 (83%) | 334 (94%) |

| (+) HLA-C (C/C) | 14 (40%) | 5 (46%) | 3 (50%) | 2 (40%) | 9 (38%) | 52 (16%) |

| (+) CCR5wt/Δ32 | 9 (26%) | 2 (18%) | 1 (17%) | 1 (20%) | 7 (29%) | 33 (10%) |

| Homozygous (C/C) for SNP: rs9264942 of HLA-C | ||||||

| HLA-C (C/C) positive | 18 (39%) | 8 (47%) | 6 (67%) | 2 (25%) | 10 (35%) | 54 (15%) |

| (+) HLA-B*57:01 | 4 (22%) | 3 (38%) | 3 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (10%) | 2 (4%) |

| (+) CCR5wt/Δ32 | 7 (39%) | 3 (38%) | 2 (33%) | 1 (50%) | 4 (40%) | 2 (4%) |

| HLA-C (C/C) negative | 28 (61%) | 9 (53%) | 3 (33%) | 6 (75%) | 19 (66%) | 300 (85%) |

| (+) HLA-B*57:01 | 7 (25%) | 3 (33%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (50%) | 4 (21%) | 18 (6%) |

| (+) CCR5wt/Δ32 | 4 (14%) | 3 (33%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (50%) | 3 (16%) | 33 (11%) |

| CCR5wt/Δ32 deletion | ||||||

| CCR5wt/Δ32 positive | 11 (24%) | 4 (24%) | 2 (22%) | 2 (25%) | 7 (24%) | 35 (10%) |

| (+) HLA-B*57:01 | 2 (18%) | 2 (50%) | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (6%) |

| (+) HLA-C (C/C) | 7 (24%) | 3 (75%) | 2 (100%) | 1 (50%) | 4 (57%) | 2 (6%) |

| CCR5wt/Δ32 negative | 35 (76%) | 13 (77%) | 7 (78%) | 6 (75%) | 22 (76%) | 319 (90%) |

| (+) HLA-B*57:01 | 9 (26%) | 4 (31%) | 2 (29%) | 2 (33%) | 5 (23%) | 18 (6%) |

| (+) HLA-C (C/C) | 11 (31%) | 5 (39%) | 4 (67%) | 1 (17%) | 6 (27%) | 52 (16%) |

LTNP, long-term non-progressors; LTNP-VC, viraemic controllers; LTNP-EC, elite controllers; LTNP-NC, viraemic non-controllers.

In the LTNP subgroup, and specifically in the LTNP-EC subgroup (n=9), we observed that in 44.4% of the cases more than one genetic marker was simultaneous present (n=4). Both the 33.3% of patients who presented the rs2395029 SNP (HLA-B*57:01) as well as the 22.2% of those who presented CCR5wt/Δ32 also had the homozygous rs9264942 SNP. Only one patient belonging to this subgroup had all three genetic markers.

In the LTNP-VC subgroup (n=8), at least 2 patients (25%) presented 2 protective genetic markers at the same time: CCR5wt/Δ32 deletion, combined simultaneously with the rs2395029 SNP (HLA-B*57:01) in one of the cases and the homozygous rs9264942 SNP in the other case. In the LTNP-NC subgroup (n=29), 5 patients presented a combination of two of these markers, of which 4 of them simultaneously presented CCR5wt/Δ32 and the homozygous rs9264942 SNP, and one patient jointly presented the rs2395029 SNP (HLA-B*57:01) and the homozygous rs9264942 SNP.

In the group of progressors (n=354), 6 patients presented a combination of two of these genetic markers (1.7%), of which 2 patients (0.6%) presented the homozygous rs9264942 SNP and the rs2395029 SNP (HLA-B*57:01), another 2 patients (0.6%) presented CCR5wt/Δ32 deletion and the homozygous rs9264942 SNP, and a further 2 patients (0.6%) presented CCR5wt/Δ32 deletion and the rs2395029 SNP (HLA-B*57:01).

DiscussionThis is the first national study analysing the main genetic markers associated with slow HIV-1 progression, and more specifically in the Galician population.

According to the literature, the prevalence of the polymorphism (CCR5-Δ32) varies among the different ethnic groups; in the populations of northern Europe, it is present in 10–20%.6,7 In the case of the HLA-B*57:01 allele, its prevalence is around 1–10% in Caucasians, Africans and Asians,7 although a recent epidemiological study (EPI 109839) found that the prevalence of this allele in Spain is above 6%, peaking at 6.5% in Caucasians.15 Furthermore, the prevalence of the HLA-B*27:05 allele is present in 1.4–8% of people on the main continents.7 This percentage is higher among Caucasians (8–20%), with a higher prevalence in the Scandinavian countries.16

These prevalence data are consistent with what we found in our patient series, although in the case of the HLA-B*57:01 allele, it is surprising that the frequency of this allele is higher (8.2%) than that published at the national level (6.5%).

In our study, the presence of the HLA-B*57:01 allele, the homozygous rs9264942 SNP and CCR5wt/Δ32 deletion were correlated with a better prognosis for HIV-1 infection progression. However, in our patient series no evidence was found of a protective effect from the HLA-B*27:05 allele in HIV-1 infection progression. A Spanish study of seroprevalent patients found a HLA-B*27 allele frequency of 23% in 30 LTNP viral replication controllers (LTNP-EC and LTNP-VC),17 while in our study it was only detected in 2 LTNP-NC patients. This inconsistency could be due to the fact that the presence of this allele varies by the latitude of the patient's country of origin, and its prevalence is practically zero in regions near the equator (0%) and extremely high in countries close to the Arctic (40%).18 Another reason that could explain this discrepancy could be the presence of “frailty bias” which tends to happen in studies on fatal diseases, such as HIV-1 infection.19 This type of bias usually occurs in studies that present a small number of individuals in which a certain population is enhanced, as happens in cohort studies that exclusively include LTNP, in which some of the study variables are correlated with a specific event, such as slow progression. But when these variables are analysed in a much larger patient cohort, and when, as in our study, progressor patients are also included, this correlation is minimised or disappears.7 Furthermore, other authors have stressed the existing relationship between different genes, with a synergistic effect, whose association could possibly be more important than that of HLA-B*27:05 itself in terms of mediating and modulating disease progression.8,18,20–22

Regarding the LTNP patient subgroup, one or more of these genetic markers was found to be present, which makes us think about the existence of synergies between these combinations, but due to the small number of viraemic controller patients (n=17) we can only speak of trends. The most salient piece of data was that 67% of the patients who simultaneously presented the rs2395029 SNP (HLA-B*57:01) and the homozygous rs9264942 SNP behaved as LTNPs (n=4), and of these, 75% belonged to the LTNP-EC subgroup, which coincides with that previously reported.8,14,23 Therefore this result reinforces the theory that cellular immunity plays an important role in delaying disease development.

ConclusionsThe prevalence of the genetic markers studied in the Galician population is consistent with that published in the literature. It should be noted that the frequency found for the HLA-B*57:01 allele was higher than that published at the national level. The genetic markers studied were correlated with a better HIV-1 infection progression prognosis, except for the HLA-B*27:05 allele. Due to its low frequency in our population, its presence could not be correlated with a protective effect against infection progression.

FundingINBIOMED 2009-063 Xunta de Galicia.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Biomedical Capacities Support Programme (BIOCAPS). FP7-REGPOT316265.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez-Da Silva A, Miralles C, Ocampo A, Valverde D. Estudio de la prevalencia de marcadores genéticos asociados a la lenta progresión del virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana tipo 1 en la población gallega. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2017;35:104–107.