Rickettsia diseases are a group of tick-borne transmitted diseases, classified into 2 large groups: spotted fevers and typhus fevers. In addition, a new condition has been described recently, known as tick-borne lymphadenopathy.

A retrospective series is presented of paediatric cases of rickettsia diseases diagnosed in 2013 and 2014. A total of 8 patients were included, of which 2 of them were diagnosed as Mediterranean spotted fever, and 6 as tick-borne lymphadenopathy. Rickettsia slovaca, Rickettsia sibirica mongolitimonae, and Rickettsia massiliae were identified in 3 of them. Aetiology, clinical features and treatment carried out in each of them are described.

The interest of these cases is that, although most have a benign course, the high diagnostic suspicion and early treatment seem to be beneficial for its outcome.

Las rickettsiosis constituyen un grupo de enfermedades transmitidas por la picadura de garrapatas, clasificándose en 2 grandes grupos: fiebres manchadas y fiebres tifíticas. Además, recientemente se ha descrito una nueva entidad conocida como linfadenopatía por picadura de garrapata.

Presentamos una serie retrospectiva de casos pediátricos diagnosticados de rickettsiosis durante los años 2013–2014. Se incluyeron un total de 8 pacientes, 2 de ellos diagnosticados de fiebre botonosa mediterránea y 6 de linfadenopatía por picadura de garrapata, identificándose en 3 de ellos Rickettsia slovaca, Rickettsia sibirica mongolitimonae y Rickettsia massiliae. Se describen la etiología, las características clínicas y el tratamiento realizado en cada uno de ellos.

El interés de estos casos radica en que aunque mayoritariamente presentan un curso benigno, la elevada sospecha diagnóstica y el inicio precoz del tratamiento parecen ser beneficiosos en su evolución.

There are several zoonotic diseases that are primary transmitted by ticks, which act as vectors for different pathogens. Rickettsiosis are one of these diseases, with a heterogeneous geographic distribution, transmitted by these arthropods. They are classified into two groups: spotted fevers, mainly Mediterranean spotted fever (MSF) caused by Rickettsia conorii, and typhus fevers, mainly murine typhus caused by R. typhi. In addition, a new condition has been described recently, known as tick-borne lymphadenopathy or TIBOLA. Although it is grouped with the spotted fevers, it presents certain clinical and aetiological differences from these, which is why it is defined as an independent entity.1

In recent years, greater clinical suspicion and improved diagnostic techniques have led to an increase in reported paediatric cases.

Our hospital is the referral hospital for a large paediatric population coming from rural areas, and often the families come to our emergency department where the children can be diagnosed. The objective of our study is to describe the epidemiological change detected in rickettsiosis infections in recent years in our department.

MethodsRetrospective, descriptive study of paediatric patients (0–14 years) diagnosed with rickettsiosis in our department from January 2013 to December 2014.

The following data were collected: age, time of year, symptomatology, supplementary tests, treatment received and clinical course after outpatient follow-up. The diagnosis was made via compatible symptoms, serology testing (immunoglobulins IgM and IgG against R. conorii using enzyme immunoassay) and/or molecular biology techniques (PCR amplification of a fragment of the intergenic spacer 23S-5S rRNA and reverse phase hybridisation with species-specific waves).2

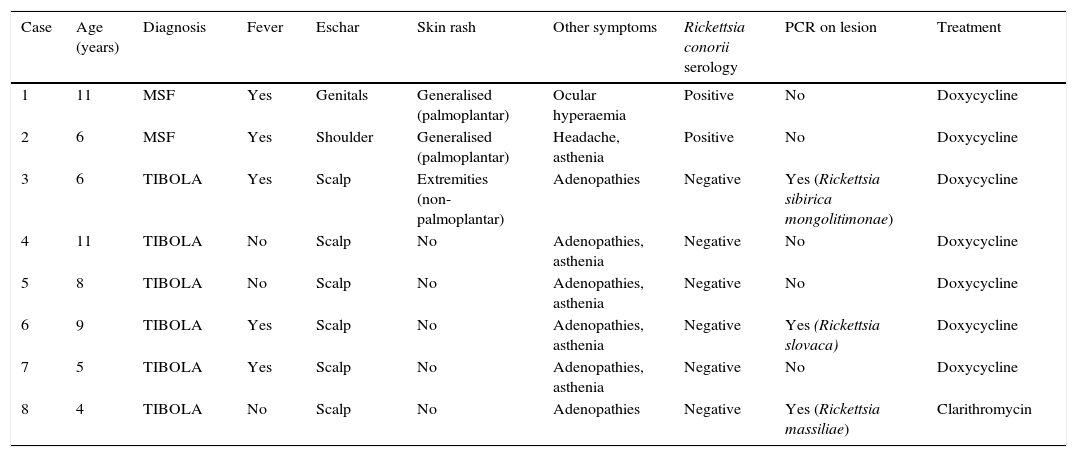

ResultsEight patients were diagnosed, from the ages of 4–11 years (median 7). Table 1 summarises the aetiology, clinical characteristics and treatment given to each of them.

Patient descriptions.

| Case | Age (years) | Diagnosis | Fever | Eschar | Skin rash | Other symptoms | Rickettsia conorii serology | PCR on lesion | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11 | MSF | Yes | Genitals | Generalised (palmoplantar) | Ocular hyperaemia | Positive | No | Doxycycline |

| 2 | 6 | MSF | Yes | Shoulder | Generalised (palmoplantar) | Headache, asthenia | Positive | No | Doxycycline |

| 3 | 6 | TIBOLA | Yes | Scalp | Extremities (non-palmoplantar) | Adenopathies | Negative | Yes (Rickettsia sibirica mongolitimonae) | Doxycycline |

| 4 | 11 | TIBOLA | No | Scalp | No | Adenopathies, asthenia | Negative | No | Doxycycline |

| 5 | 8 | TIBOLA | No | Scalp | No | Adenopathies, asthenia | Negative | No | Doxycycline |

| 6 | 9 | TIBOLA | Yes | Scalp | No | Adenopathies, asthenia | Negative | Yes (Rickettsia slovaca) | Doxycycline |

| 7 | 5 | TIBOLA | Yes | Scalp | No | Adenopathies, asthenia | Negative | No | Doxycycline |

| 8 | 4 | TIBOLA | No | Scalp | No | Adenopathies | Negative | Yes (Rickettsia massiliae) | Clarithromycin |

MSF: Mediterranean spotted fever; PCR: polymerase chain reaction.

Two patients were diagnosed with MSF, seen during July and August. Both presented necrotic eschar, high fever and maculopapular rash, with palmoplantar involvement. Neither remembered a history of tick bite, although both reported having close contact with animals. Case 1 also presented unilateral conjunctival hyperaemia, indicative of oculoglandular rickettsiosis.

A total of 6 patients were diagnosed with TIBOLA, all presenting necrotic eschar and tender, regional lymphadenopathies. Unlike the MSF cases, these did not occur during the summer months, and only two remembered a recent tick bite.

Serology testing for R. conorii was ordered for all of them, with positive results only in the two diagnosed with MSF. In three of the six remaining patients, testing was expanded with molecular biology techniques (PCR) in a cutaneous biopsy sample of the eschar, which gave rise to the aetiological diagnosis of the infection.

All were treated with doxycycline for 7–10 days, except for one patient who received clarithromycin. Clinical progress was excellent, except for the presence of a small area of alopecia on the scalp in patients who had a necrotic eschar in that area.

DiscussionRickettsiosis are a group of zoonotic diseases that usually have a benign and self-limited progression, although they can follow a severe course in patients with risk factors such as diabetes mellitus, heart failure or the elderly. They are caused by gram-negative bacteria, transmitted by haematophagic arthropods (mainly ticks and fleas) and are primarily distributed in Hungary, France and Spain, specifically in Ceuta and La Rioja, followed by Melilla, Navarra and Murcia.1,3,4

MSF is the most common rash-causing rickettsiosis in the Mediterranean countries, first described in Tunisia in 1910. The incidence rate in Spain is 0.36 cases per 100,000 people, with a mortality rate under 1%, according to recent publications.3 Although other ticks can transmit it, the main vector is the dog tick (Rhipicephalus sanguineus). The usual hosts are small rodents and dogs, with humans being an accidental host.1–4 As we observed in our patients, unlike other rickettsiosis, MSF primarily occurs in the summer, with an incubation period between 4 and 20 days. Clinically, the presence of a necrotic eschar with an erythematous halo, called a tache noire (Fig. 1), along with fever and generalised maculopapular rash with palmoplantar involvement, is characteristic of almost all of the reported cases. Curiously, and unlike what occurs in most cases, neither of our two patients presented a necrotic lesion on the scalp, the most common location in paediatric patients.1 The definitive diagnosis is made using serology testing against R. conorii, since this is the main implicated species and is also the only one for which commercial assays exist. Even so, the initial clinical suspicion will be of great importance in those patients with compatible symptomatology, even in the absence of a clear history of tick bite, since the serological determination can be negative in the early stages of the infection, with the seroconversion often observed during the convalescent phase. The current treatment is based on the use of oral doxycycline. Studies conducted with short doxycycline regimens in a single day (200mg/12h or 5mg/kg/12h) have been shown to be as effective as classical, longer regimens of up to 10 days. Regarding the use of macrolides, they can be an alternative treatment in select cases. Even so, it seems that the in vitro antibiotic sensitivity is somewhat heterogeneous. Erythromycin treatment is ineffective, but the alternative with josamycin (50mg/kg/12h 5 days) or clarithromycin (15mg/kg/12h 5 days)5–7 is likely to be appropriate.

In recent years, a new entity known as tick-borne lymphadenopathy, first observed in Hungary in 1997, has been reported. It has received different names since it was identified: TIBOLA for “tick-borne lymphadenopathy” in its initial description; DEBONEL for “dermacentor-borne necrosis erythema lymphadenopathy”, defined by Oteo et al., due to the greater implication of the vector Dermacentor marginatus; and the latest descriptions, SENLAT, for “scalp eschar and neck lymphadenopathy after tick bite”.4,8–11 Although the main causative agent is R. slovaca, in recent years other agents have been described, such as R. rioja, R. sibirica mongolotimonae and R. massiliae, in addition to other bacteria not in the Rickettsia spp. genus, such as Bartonella henselae and Francisella tularensis.2,11–13 As observed in our patients, and unlike MSF, it primarily occurs during the spring, and practically all cases present a necrotic eschar on the scalp and regional tender adenopathies (often occipital and cervical), giving rise to its name. It can be associated with varied symptomatology, such as fever, asthenia, joint and muscle pain or headache, as well as the onset of a maculopapular rash that can be confused with MSF, but with a distribution primarily on the trunk and not on the extremities, as we could observe in one of our patients.1,4,10 It is usually an entity with a benign progression, especially in paediatric patients, whose most common sequela is residual alopecia in the eschar area.

It is known that the serological techniques against R. conorii can yield positive results due to cross-reactivity with other Ricketsia spp. species, up to 45% in the case of R. slovaca.14 Even so, none of our patients was positive. This may be due to the fact that they were not determined in very early stages of the infection and serology was not performed in the convalescent phase. Currently, PCR techniques are used to give a definitive diagnosis. They may be performed in blood (EDTA or citrate tube) or CSF, or on a skin biopsy from the necrotic eschar, a site that will give a higher diagnostic performance due to the lower percentage of haematogenous spread.

Treatment with short regimens of doxycycline or with macrolides such as josamycin may be effective, although there are few publications which corroborate this, probably because little is known about this new entity. To date, the most established recommendation is a 7–14 day regimen with doxycycline (100mg/12h or 5mg/kg/12h). An alternative in those under 8 years old or in pregnant women are macrolides, primarily clarithromycin (15mg/kg/day every 12h) for 7–10 days.4,15

Regarding previous series where most of the described cases of rickettsia infections corresponded to MSF, in our study the high proportion of TIBOLA cases stands out, surely due to our improved knowledge of the disease in recent years and to the increased degree of suspicion when assessing children with a tache noire or tick bite.

Although they are mostly diseases with a benign course, the higher diagnostic suspicion and the early start of treatment appear to have beneficial effects on the clinical course of the disease. More studies are needed in the paediatric population to give reliable recommendations about the treatment and its duration in these diseases.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The Carlos III Institute of Health National Microbiology Centre, Majadahonda (Madrid), for having identified the Rickettsia species.

Please cite this article as: Monterde-Álvarez ML, Calbet-Ferré C, Rius-Gordillo N, Pujol-Bajador I, Ballester-Bastardie F, Escribano-Subías J. Rickettsiosis tras la picadura de una garrapata: una clínica sutil en muchas ocasiones, debemos estar atentos. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2017;35:100–103.