A 67-year-old male with previous medical history of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, ischemic myocardiopathy. The patient received a deceased-donor kidney transplant one month prior to admission for end stage kidney disease. He was borned and raised in Basque Country, Spain, and had worked as ship captain based in Guatemala, and travelling around the world. His immunosuppressant regimen consisted of prednisone 15mg od, mycophenolate 720mg bid and tacrolimus 1mg bid and was under prophylactic treatment with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and valganciclovir.

He was admitted to the emergency department presenting 10 days of dyspnoea, productive cough and fever. On arrival he had severe hypoxemic respiratory failure (arterial pressure of oxygen of 64mmHg with a fraction of inspired oxygen of 60%). The chest X-ray showed bilateral consolidations. Laboratory data revealed 16000 leucocytes (normal range 4000−11000), C reactive protein of 36mg/L (normal range<1), and procalcitonin of 1.88ng/mL (normal range<0.5). Empirical treatment with meropenem, linezolid, levofloxacin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and isavuconazole was started for resistant and atypical bacteria, Pneumocystis and Aspergillus coverage. As he continued to deteriorate with increasing oxygen requirements, he was started on invasive mechanical ventilation and transferred to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU).

Blood cultures, urine antigens for S. pneumoniae and Legionella, Cryptococcus serum antigen, Strongyloides serology, Aspergillus serum antigen and quantitative serum PCR for cytomegalovirus (CMV) were performed with negative results. The patients pre-transplant serology was positive for Epstein−Barr virus, CMV, herpes simplex virus, varicella zoster virus and toxoplasma. Screening for tuberculosis was not performed pre-transplant. The donor passed away due to a cerebrovascular accident. Receptors from the same donor had no infectious diseases complications to the date.

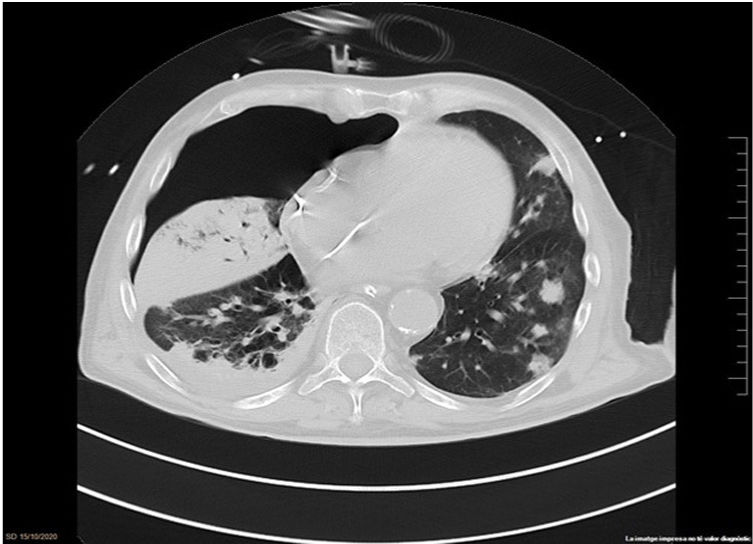

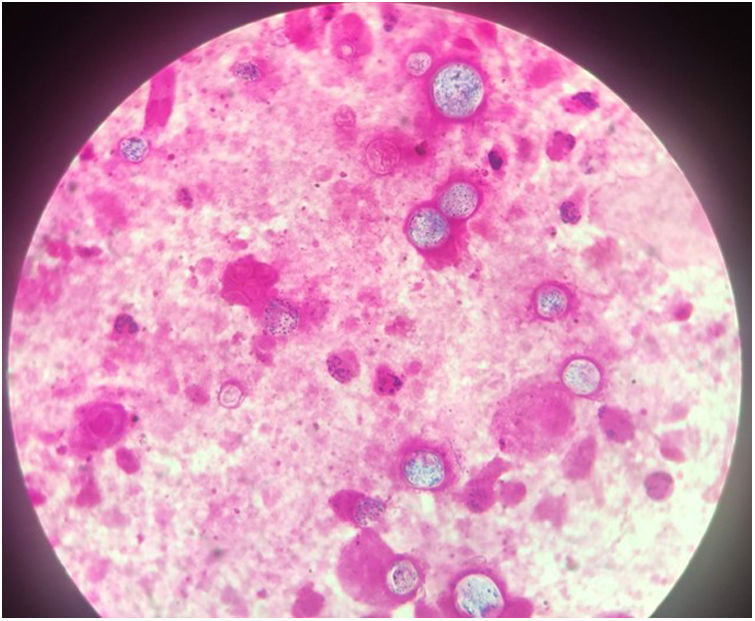

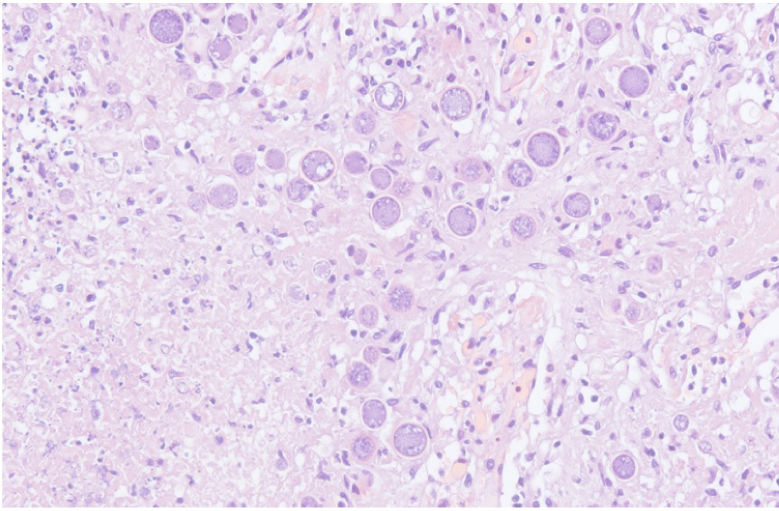

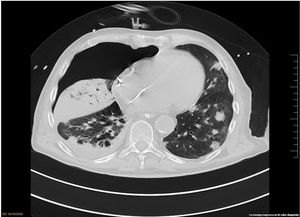

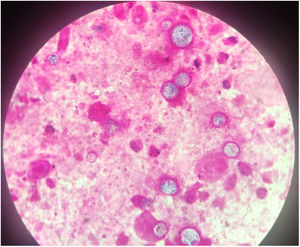

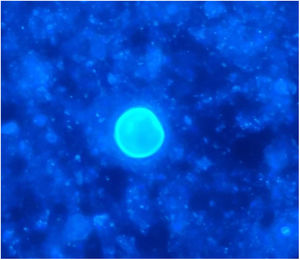

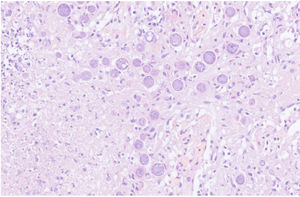

The chest-CT scan showed an extensive right lung consolidation and bilateral nodular consolidative foci (Fig. 1). Empiric liposomal amphotericin B was added to improve fungal coverage. A bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed. Multiplex PCR for respiratory viruses and bacteria (influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, CMV, adenovirus, coronavirus, rhinovirus, Legionella, Mycoplasma, Chlamydia, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Moraxella, Serratia, S. aureus, S. pneumoniae) were negative. No acid-fast bacilli were observed in the auramine stain. On direct examination with Gram and Calcofluor stain of the BAL a microorganism compatible with C. posadasii was found, and later confirmed on cultures (Figs. 2 and 3). The patient continued to require high oxygen requirements and eventually developed multiorgan failure. Nine days after admission the patient died. On the necropsy, spherules full of endospores were found within the pulmonary parenchyma, confirming an invasive fungal infection (Fig. 4).

Pneumonia in immunocompromised patients like solid organ receptors can be challenging. The differential diagnosis should always include opportunistic infections, elapsed time since the transplantation, donor and receptor infectious screening, immunosuppressive regimen and epidemiological factors of the patient.1 The diagnostic process should include microbiological tests (blood and sputum cultures, tuberculosis and Legionella screening, fungal biomarkers, PCR for CMV and other respiratory viruses), radiological imaging (chest-CT scan) and invasive procedures (bronchoscopy for bronchoalveolar lavage or tissue biopsy)2 as we did in our patient.

Coccidioidomycosis is a fungal disease caused by Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii. These dimorphic fungi are endemic in the southwestern of the United States of America, Mexico and some areas of Central and South America.3 It is a common cause of community adquired pneumonia in endemic areas and the disease can be very aggressive in immunosuppressed hosts in which extrapulmonary infection is more prevalent.4

We should consider coccidioidomycosis in patients with compatible clinical symptoms, radiological findings, epidemiology and positive serology. The diagnosis is definitive with a positive culture or a biopsy specimen demonstrating spherules.5 Guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases recommend screening for Coccidioides in transplant donor and recipients with clinical history, chest X-ray and serology when they have travelled or lived in areas with a high prevalence.2 Before screening and prophylaxis were routinely performed, the incidence of coccidioidomycosis in this population was around 7-8%, whereas now it has decreased to less than 2%.6

Treatment of Coccidioidomycosis is based on azoles. Treatment of pulmonary coccidioidomycosis in immunosuppressed patients can be done with fluconazole or posaconazole/isavuconazol; however, in severe forms of the disease, amphotericin is recommended. The duration of the treatment should be over one year. Prophylaxis in solid organ transplant recipients with positive serology is made with low dose of fluconazole during a year.7

Following this case, a new protocol has been updated in our center, screening of endemic infectious diseases in recipients of solid transplant that have travelled or lived in areas with endemic infectious diseases.

ConclusionIn this globalized world, clinicians should be alert and updated for endemic infectious diseases, specially in immunosuppressed patients. Travel history is key in identifying patients that might be at risk of having endemic infections. Coccidioidomycosis is rare but potentially severe disease in transplant recipients.