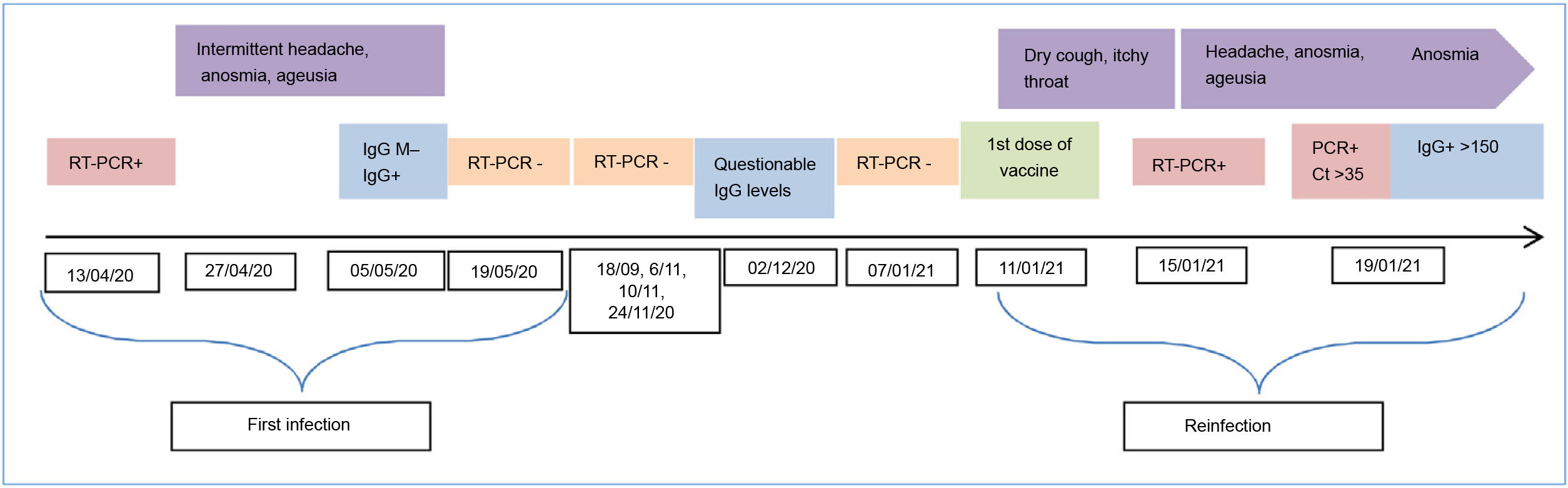

We present a case with solid evidence of SARS-COV-2 reinfection. The extensive monitoring of hospital workers during the SARS-COV-2 pandemic played a key role in identifying this suspicion of reinfection confirmed by sequencing. It should be noted that both infections were diagnosed from the contact study carried out among workers when cases of COVID-19 were identified in hospitalised patients without COVID-19. The first infection occurred during the first spike in the pandemic in April 2020. The worker was asymptomatic, and on 13/04/2020 she underwent a nasopharyngeal nucleic acid amplification test in the context of an occupational contact study regarding a positive patient. The RT-PCR result was positive with a Ct of 23.55 (<35). The positive test was followed by mild symptoms (headache, anosmia and ageusia). Thirty-seven (37) days after diagnosis, the RT-PCR was negative and an immune response was identified (IgG index value 3.98; positive >1.6; COVID-19 VIRCLIA® IgG monotest, VIRCELL).

In the following months, as mandated by the hospital-acquired infection control programme, several RT-PCR tests were performed with negative results (Fig. 1). Eight (8) months later, IgG levels had decreased significantly (IgG 1.55). Most people have an immune response after infection with antibodies,1 and although they tend to decrease during the following months, many studies indicate that the neutralising activity is maintained for up to six or eight months.2,3 This immune response is associated with protection against reinfection, at least in the short term.4

The second infection was also detected by contact study. It was diagnosed on 15/01/2021 by RT-PCR. The worker presented mild symptoms (cough and itchy throat) which she had not reported. We believe that although the early detection programme for SARS-COV-2 infection among workers was known and correctly implemented, since she had already had the infection and she was aware of her immune response, she did not suspect SARS-COV-2 infection and therefore did not notify the occupational health department. Moreover, a few days previously (11/01/21) she had received the first dose of the Pfizer vaccine. In this case, we know that the reinfection occurred after the 07/01/21, since an RT-PCR was obtained on that day with a negative result. We believe that the worker must have already been infected on the day of the vaccination, since on 15/01/21 she already had symptoms and the average incubation period is 5 to si6x days. In addition, 4 days after diagnosis, she underwent an RT-PCR and determination of IgG of the S1 subunit of SARS-CoV-2 (anti-S), in which low viral load (Ct >35) and very high immune response levels (>150) were detected. The dynamics of the immune response in humans has been described. It is possible to detect total antibodies, IgM and IgG, with increasing sensitivity over the course of the infection, which is greater than 90% in the second week after the onset of symptoms.5,6 In our case, the fact that such high anti-S IgG levels were detected a few days after the onset of symptoms leads us to consider a possible booster effect, mainly associated with the vaccine, although the anti-N IgG are not available. The inoculation of a single dose of the mRNA vaccines in an individual who has had the infection is known to give rise to an exponential increase in the immune response.7 Another publication8 describes that a single dose of mRNA vaccine produces an immediate immune response in seropositive people, with post-vaccination antibody titres similar to or higher than seronegative people with two doses of the vaccine.

Sequencing is required to confirm reinfection and differentiate it from persistent RT-PCR. There are sporadic cases of reinfection confirmed by sequencing around the world.9,10 In our case, the opportunity to sequence the two samples confirmed reinfection by showing different lineages. The sequencing technology used was Illumina (MiSeq platform) GISAID for the first infection EPI_ISL_1595836 and GISAID for the reinfection EPI_ISL_1595838. In the case of samples with low viral loads, the laboratory increases the amount of RNA extract to have sufficient material available for sequencing. The first infection corresponded to a member of Clade 20B (B.1.1 lineage) and the second corresponded to Clade 20E (B.1.177 lineage). The lineage of the second sample began to circulate in Spain as of the summer of 2020.

The implementation of the comprehensive diagnostic and monitoring programme for workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in our centre allowed us to detect this case. We believe that this is important for the good control of hospital-acquired infection.