Our aims were to investigate the adherence to national guidelines of initial antiretroviral therapy (ART) in the Spanish multicenter CoRIS cohort during the years 2010–2015, to identify the reasons for the prescription of nonrecommended treatments, and to explore the role of institutional constraints to guideline compliance.

MethodsART regimens were classified as recommended, alternative or nonrecommended according to the guidelines. Physicians were asked the reasons for prescribing nonrecommended regimens. Factors associated with the prescription of non recommended regimens were assessed using multivariable logistic regression.

ResultsDuring the study period, 586 (10.7%) of 5479 patients who started ART were given a regimen not recommended in the guidelines. The most frequent reasons for prescribing nonrecommended regimens were: enrolment in clinical trials (43.3%), comorbidities and/or interactions (10.2%), pregnancy (8.7%), and cost (7.7%). Among 37 participating centers, 16 (43%), treating 3561 patients, reported limitations related with the cost of ART, and 20 (54%), treating 1365 patients, reported restrictions for prescribing at least one recommended antiretroviral. In multivariable analysis, a higher risk of receiving nonrecommended regimens was associated with male gender, HIV acquisition by heterosexual transmission, low viral loads, initiation of treatment during the years 2011 to 2015, and initiation of treatment in a center with restricted access to at least one antiretroviral drug.

ConclusionsCompliance to clinical guidelines was high. A high proportion of centres reported cost limitations for ART or restricted access to at least one recommended antiretroviral drug, with a significant impact on the choice of initial regimens.

Nuestros objetivos fueron investigar la adecuación del tratamiento antirretroviral (TAR) inicial a las guías nacionales en la cohorte multicéntrica española CoRIS durante los años 2010-2015, identificar las razones para la prescripción de pautas no recomendadas y estudiar la influencia de limitaciones institucionales en el cumplimiento de las guías.

MétodosSe clasificaron las pautas de TAR en recomendadas, alternativas o no recomendadas según las guías de GeSIDA/Plan Nacional sobre el sida. Se preguntaron las razones para haber prescrito pautas no recomendadas a los médicos prescriptores. Se evaluaron los factores asociados a la prescripción de pautas no recomendadas mediante regresión logística multivariable.

ResultadosDurante el periodo de estudio 586 (10,7%) de 5.479 pacientes que iniciaron TAR recibieron una pauta no recomendada. Las razones más frecuentes para prescribir pautas no recomendadas fueron: participación en ensayo clínico (43,3%), comorbilidades y/o interacciones (10,2%), embarazo (8,7%) y coste (7,7%). Entre los 37 centros participantes 16 (43%), que incluían 3.561 pacientes, referían limitaciones en el coste del TAR y 20 (54%), que incluían 1.365 pacientes, referían restricciones para la prescripción de al menos un fármaco recomendado. En el análisis multivariable el riesgo de recibir una pauta no recomendada se asoció a ser varón, adquisición del VIH por vía heterosexual, carga viral baja, inicio del tratamiento durante los años 2011 a 2015 e inicio del tratamiento en un centro con acceso restringido al menos a un antirretroviral.

ConclusionesEl cumplimiento de las guías de TAR fue elevado. Una alta proporción de centros refirieron limitaciones de coste para el TAR o acceso restringido al menos a uno de los fármacos antirretrovirales recomendados; esto último influyó en la elección de pautas no recomendadas.

Clinical guidelines for the treatment of HIV-infected patients are developed by many scientific societies and institutional boards and are widely available.1–3 Despite this, there is little information on the compliance to HIV treatment guidelines and the factors that might influence it.

Studies in different populations have found variable adherence to ART guidelines, ranging from 53 to 83% in the United States4–6 to over 90% in several European countries.7–10 The reasons why physicians prescribe antiretroviral drug regimens that are not recommended by the guidelines are not well known. Some studies have tried to identify factors associated with the prescription of nonrecommended regimens.4,5,7,9–11 However, none of these studies, with the exception of one,9 specifically investigated the reasons for noncompliance to the guidelines among the prescribing physicians.

The Spanish national guidelines for HIV treatment are published jointly by the Spanish AIDS Study Group (GeSIDA) and the National Plan for AIDS (PNS); they are updated annually and are widely known in Spain.12 Only two studies have assessed the adherence to antiretroviral treatment (ART) guidelines in our country in earlier years10,11: both found a high percentage (over 90%) of compliance to the guidelines for initial ART. However, since both studies were published treatment guidelines have changed substantially, and during the later years cost-containment policies have been implemented in the Spanish healthcare system.13–15 Whether these changes could have influenced the adherence to the guidelines is not known.

The aims of this study were to investigate the adherence to national guidelines of initial ART in the Spanish CoRIS cohort during the years 2010–2015, to identify the reasons why physicians prescribe treatments that are not recommended by the guidelines, and to explore possible institutional constraints to guideline compliance.

Materials and methodsPatients and data collectionPatients were selected from the Cohort of the Spanish AIDS Research Network (CoRIS), which has been described in detail elsewhere.16,17 CoRIS is a prospective multicentre cohort of HIV-positive treatment-naïve patients aged >13 years, recruited from 42 centres from 13 Autonomous Regions in the Spanish public healthcare system. We included patients who started their first ART from January 2010 to November 2015. Five of the centres did not have any patients starting treatment during the study period and therefore were not included in the analysis.

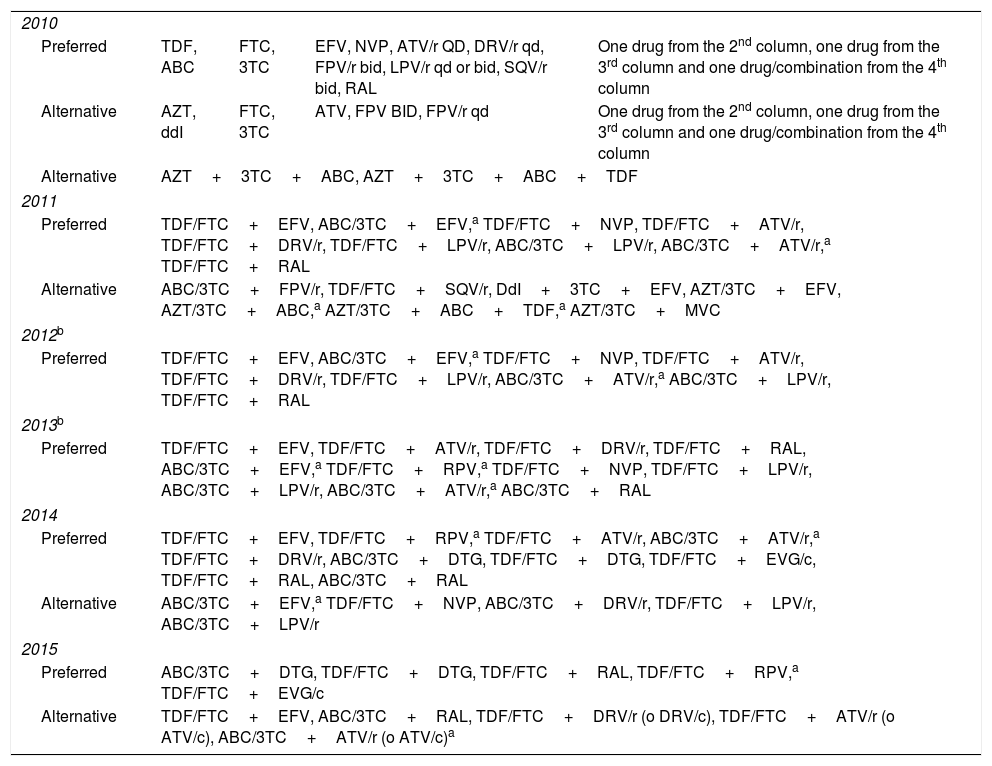

During the study period the guidelines were updated yearly, and changes introduced were taken into account from the date of publication of each update.18–23 Treatments were classified as preferred, alternative or not recommended, according to the guidelines’ recommendations for initial ART. The recommendations for treatment initiation in each period are shown in Table 1. Any treatment that was not classified as preferred or alternative by the guidelines was considered not recommended. We analyzed only the first treatment administered and any further treatment changes were ignored.

Preferred and alternative drug combinations for treatment initiation in HIV-infected patients according to national guidelines, updated during the study period.

| 2010 | ||||

| Preferred | TDF, ABC | FTC, 3TC | EFV, NVP, ATV/r QD, DRV/r qd, FPV/r bid, LPV/r qd or bid, SQV/r bid, RAL | One drug from the 2nd column, one drug from the 3rd column and one drug/combination from the 4th column |

| Alternative | AZT, ddI | FTC, 3TC | ATV, FPV BID, FPV/r qd | One drug from the 2nd column, one drug from the 3rd column and one drug/combination from the 4th column |

| Alternative | AZT+3TC+ABC, AZT+3TC+ABC+TDF | |||

| 2011 | ||||

| Preferred | TDF/FTC+EFV, ABC/3TC+EFV,a TDF/FTC+NVP, TDF/FTC+ATV/r, TDF/FTC+DRV/r, TDF/FTC+LPV/r, ABC/3TC+LPV/r, ABC/3TC+ATV/r,a TDF/FTC+RAL | |||

| Alternative | ABC/3TC+FPV/r, TDF/FTC+SQV/r, DdI+3TC+EFV, AZT/3TC+EFV, AZT/3TC+ABC,a AZT/3TC+ABC+TDF,a AZT/3TC+MVC | |||

| 2012b | ||||

| Preferred | TDF/FTC+EFV, ABC/3TC+EFV,a TDF/FTC+NVP, TDF/FTC+ATV/r, TDF/FTC+DRV/r, TDF/FTC+LPV/r, ABC/3TC+ATV/r,a ABC/3TC+LPV/r, TDF/FTC+RAL | |||

| 2013b | ||||

| Preferred | TDF/FTC+EFV, TDF/FTC+ATV/r, TDF/FTC+DRV/r, TDF/FTC+RAL, ABC/3TC+EFV,a TDF/FTC+RPV,a TDF/FTC+NVP, TDF/FTC+LPV/r, ABC/3TC+LPV/r, ABC/3TC+ATV/r,a ABC/3TC+RAL | |||

| 2014 | ||||

| Preferred | TDF/FTC+EFV, TDF/FTC+RPV,a TDF/FTC+ATV/r, ABC/3TC+ATV/r,a TDF/FTC+DRV/r, ABC/3TC+DTG, TDF/FTC+DTG, TDF/FTC+EVG/c, TDF/FTC+RAL, ABC/3TC+RAL | |||

| Alternative | ABC/3TC+EFV,a TDF/FTC+NVP, ABC/3TC+DRV/r, TDF/FTC+LPV/r, ABC/3TC+LPV/r | |||

| 2015 | ||||

| Preferred | ABC/3TC+DTG, TDF/FTC+DTG, TDF/FTC+RAL, TDF/FTC+RPV,a TDF/FTC+EVG/c | |||

| Alternative | TDF/FTC+EFV, ABC/3TC+RAL, TDF/FTC+DRV/r (o DRV/c), TDF/FTC+ATV/r (o ATV/c), ABC/3TC+ATV/r (o ATV/c)a | |||

3TC, lamivudine; ABC, abacavir; ATV, atazanavir; ATV/r, atazanavir/ritonavir; ATV/c, atazanavir/cobicistat; ddI, didanosine; DRV/r, darunavir/ritonavir; DRV/c, darunavir/cobicistat; DTG, dolutegravir; EFV, efavirenz; EVG/c, elvitegravir/cobicistat; FOS, fosamprenavir; FPV/r, fosamprenavir/ritonavir; FTC, emtricitabine; LPV/r, lopinavir/ritonavir; NVP, nevirapine; RAL, raltegravir; RPV, rilpivirine; SQV/r, saquinavir/ritonavir; TDF, tenofovir.

The reasons for prescribing nonrecommended treatments were obtained from all the participating centres. Each principal investigator was sent a list of all the patients from his/her centre who started treatment with a nonrecommended regimen during the study period, and was asked to provide the reason why a preferred or alternative regimen was not prescribed. Each principal investigator contacted the prescribing physician from his/her centre and the clinical records were reviewed for each patient. After reviewing the responses of all centres, reasons for prescribing nonrecommended regimens were classified as: enrolment in clinical trial, pregnancy, comorbidities/interactions, cost, primary resistance, high viral load, other, and unknown.

Additionally, the principal investigators from all participating centres were asked to respond to an electronic survey with the following open questions referred to the study period (years 2010–2015): 1. Has there been any limitation due to the cost of ART in your center or Autonomous Region?; and 2. Has there been any drug that you were not able to prescribe in your center after it was approved as a preferred treatment by the Spanish guidelines during the study period? What drug and during what period? The centres were then classified with two binary variables (yes or no): (1) limitation to the cost of ART in the centre, and (2) restricted access to at least one antiretroviral drug. This variable was considered “yes” if the centre had no access to at least one of the preferred antiretrovirals, or it had access only under restricted circumstances that required a clinical report for requesting the drug, for more than one year.

Statistical analysisDescriptive analysis of patients’ characteristics was carried out using frequency tables for categorical variables and median and interquartile range for continuous variables.

Patients who received nonrecommended treatments because they were pregnant or enrolled in a clinical trial were classified as receiving a recommended or alternative regimen.

We calculated the prevalence and its 95% confidence intervals of nonrecommended treatments, overall and according to selected covariates, either patient-related (i.e. gender, age at ART initiation, route of transmission, CD4 count and viral load at ART initiation, chronic hepatitis B and C, education, country of origin, AIDS diagnosis and year of initiation of ART) or center-related (i.e. number of beds, limitation to the cost of ART and restricted access to at least one antiretroviral drug). Multivariable logistic regression models were used to identify independent risk factors for prescribing nonrecommended treatments.

Wald tests were used to calculate p-values. All analyses were performed using a 95% confidence level. Statistical analyses were performed in Stata software (version 14.0; Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA).

EthicsAll patients signed informed consent forms. The participation in the cohort was approved by the Ethics Committees of all the participating centres. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Madrid).

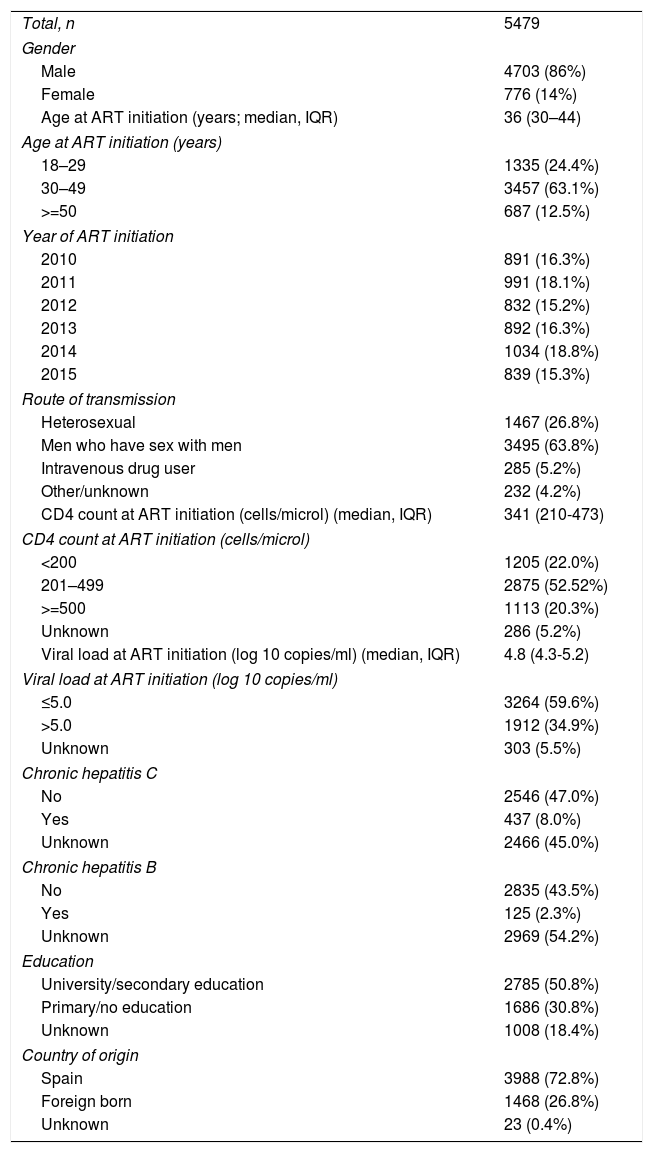

ResultsDuring the study period, 5479 patients initiated ART. The clinical and demographic characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 2. Of these patients, 586 (10.7%) received a nonrecommended treatment.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the study population.

| Total, n | 5479 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 4703 (86%) |

| Female | 776 (14%) |

| Age at ART initiation (years; median, IQR) | 36 (30–44) |

| Age at ART initiation (years) | |

| 18–29 | 1335 (24.4%) |

| 30–49 | 3457 (63.1%) |

| >=50 | 687 (12.5%) |

| Year of ART initiation | |

| 2010 | 891 (16.3%) |

| 2011 | 991 (18.1%) |

| 2012 | 832 (15.2%) |

| 2013 | 892 (16.3%) |

| 2014 | 1034 (18.8%) |

| 2015 | 839 (15.3%) |

| Route of transmission | |

| Heterosexual | 1467 (26.8%) |

| Men who have sex with men | 3495 (63.8%) |

| Intravenous drug user | 285 (5.2%) |

| Other/unknown | 232 (4.2%) |

| CD4 count at ART initiation (cells/microl) (median, IQR) | 341 (210-473) |

| CD4 count at ART initiation (cells/microl) | |

| <200 | 1205 (22.0%) |

| 201–499 | 2875 (52.52%) |

| >=500 | 1113 (20.3%) |

| Unknown | 286 (5.2%) |

| Viral load at ART initiation (log 10 copies/ml) (median, IQR) | 4.8 (4.3-5.2) |

| Viral load at ART initiation (log 10 copies/ml) | |

| ≤5.0 | 3264 (59.6%) |

| >5.0 | 1912 (34.9%) |

| Unknown | 303 (5.5%) |

| Chronic hepatitis C | |

| No | 2546 (47.0%) |

| Yes | 437 (8.0%) |

| Unknown | 2466 (45.0%) |

| Chronic hepatitis B | |

| No | 2835 (43.5%) |

| Yes | 125 (2.3%) |

| Unknown | 2969 (54.2%) |

| Education | |

| University/secondary education | 2785 (50.8%) |

| Primary/no education | 1686 (30.8%) |

| Unknown | 1008 (18.4%) |

| Country of origin | |

| Spain | 3988 (72.8%) |

| Foreign born | 1468 (26.8%) |

| Unknown | 23 (0.4%) |

Values are n (%), unless otherwise stated. IQR: interquartile range.

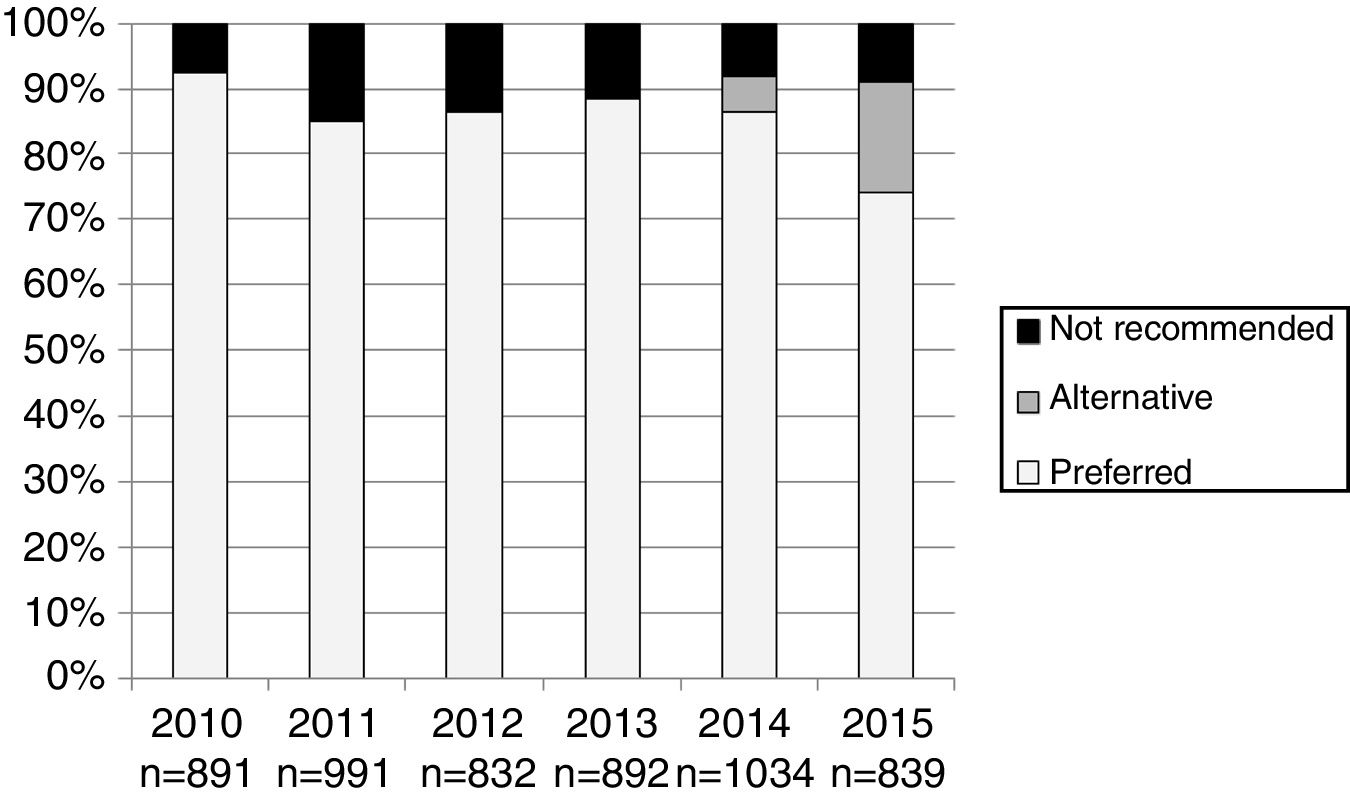

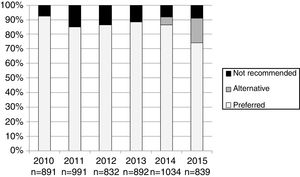

The number and proportion of patients starting ART with a preferred, alternative, and nonrecommended treatment by year of treatment initiation are shown in Fig. 1. The category “alternative treatments” was only used in the guidelines during the years 2010, 2011, 2014 and 2015. Compared to the year 2014, in 2015 there was a significant increase of alternative treatments (from 5.3% of all ART prescribed in 2014 to 17.0% in 2015) and a parallel decrease in preferred treatments (from 86.5% in 2014 to 74% in 2015: p<0.001), with a similar proportion of nonrecommended treatments (8.2% and 8.9% in 2014 and 2015, respectively). The proportion of patients receiving nonrecommended treatments showed large differences among the 13 Autonomous Regions, ranging from 1% to 20.1% of all the initial regimens (p<0.001).

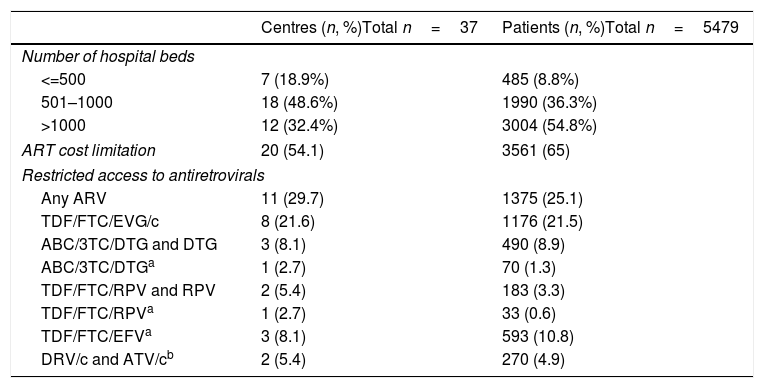

The characteristics of the participating centres are shown in Table 3. A total of 16 centres from three Autonomous Regions reported a limitation to the cost of the prescribed ART during the study period in all the centres from each of the three regions. Four additional centres from four Autonomous Regions reported cost limitations for the prescription of ART in their centre (but not in their Autonomous Region). In both cases, the cost limitation was established as a recommendation for the maximum average cost of ART per patient per year. The 20 centres with cost limitations to ART were treating 65% of the study population (Table 3). Eleven centres treating 25% of the patients reported restricted access to at least one of the recommended antiretroviral drugs during all or part of the study period; the details about the specific restrictions, and the number of centres and patients involved, are shown in Table 3.

Characteristics of the participating centres, including limitations to cost of antiretroviral therapy (ART) and restrictions of access to antiretrovirals that were recommended by the national Spanish guidelines, 2010–2015.

| Centres (n, %)Total n=37 | Patients (n, %)Total n=5479 | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of hospital beds | ||

| <=500 | 7 (18.9%) | 485 (8.8%) |

| 501–1000 | 18 (48.6%) | 1990 (36.3%) |

| >1000 | 12 (32.4%) | 3004 (54.8%) |

| ART cost limitation | 20 (54.1) | 3561 (65) |

| Restricted access to antiretrovirals | ||

| Any ARV | 11 (29.7) | 1375 (25.1) |

| TDF/FTC/EVG/c | 8 (21.6) | 1176 (21.5) |

| ABC/3TC/DTG and DTG | 3 (8.1) | 490 (8.9) |

| ABC/3TC/DTGa | 1 (2.7) | 70 (1.3) |

| TDF/FTC/RPV and RPV | 2 (5.4) | 183 (3.3) |

| TDF/FTC/RPVa | 1 (2.7) | 33 (0.6) |

| TDF/FTC/EFVa | 3 (8.1) | 593 (10.8) |

| DRV/c and ATV/cb | 2 (5.4) | 270 (4.9) |

3TC, lamivudine; ABC, abacavir; ATV/c, atazanavir/cobicistat; DRV/c, darunavir/cobicistat; DTG, dolutegravir; EFV, efavirenz; EVG/c, elvitegravir/cobicistat; FTC, emtricitabine; RPV, rilpivirine; TDF, tenofovir.

Reasons for prescribing nonrecommended treatments included enrolment in clinical trials (254 patients, 43.3%), comorbidities and/or interactions (60 patients, 10.2%), pregnancy (51 patients, 8.7%), cost (45 patients, 7.7%), high viral load (14 patients, 2.4%), primary resistance (12 patients, 2%), other (16 patients, 2.7%) and unknown (134 patients, 22.9%). “Other” reasons included unavailability of resistance test results at ART initiation in 6 patients, availability of ART regimen in an immigrant patient's country of origin in 6 patients, and patient's request in 4 patients. Most pregnant women (44 patients, 86.3%) were receiving regimens that were recommended/alternative in the guidelines for pregnant women but not recommended in the general guidelines; the majority of these women (41 patients) were receiving regimens that included zidovudine.

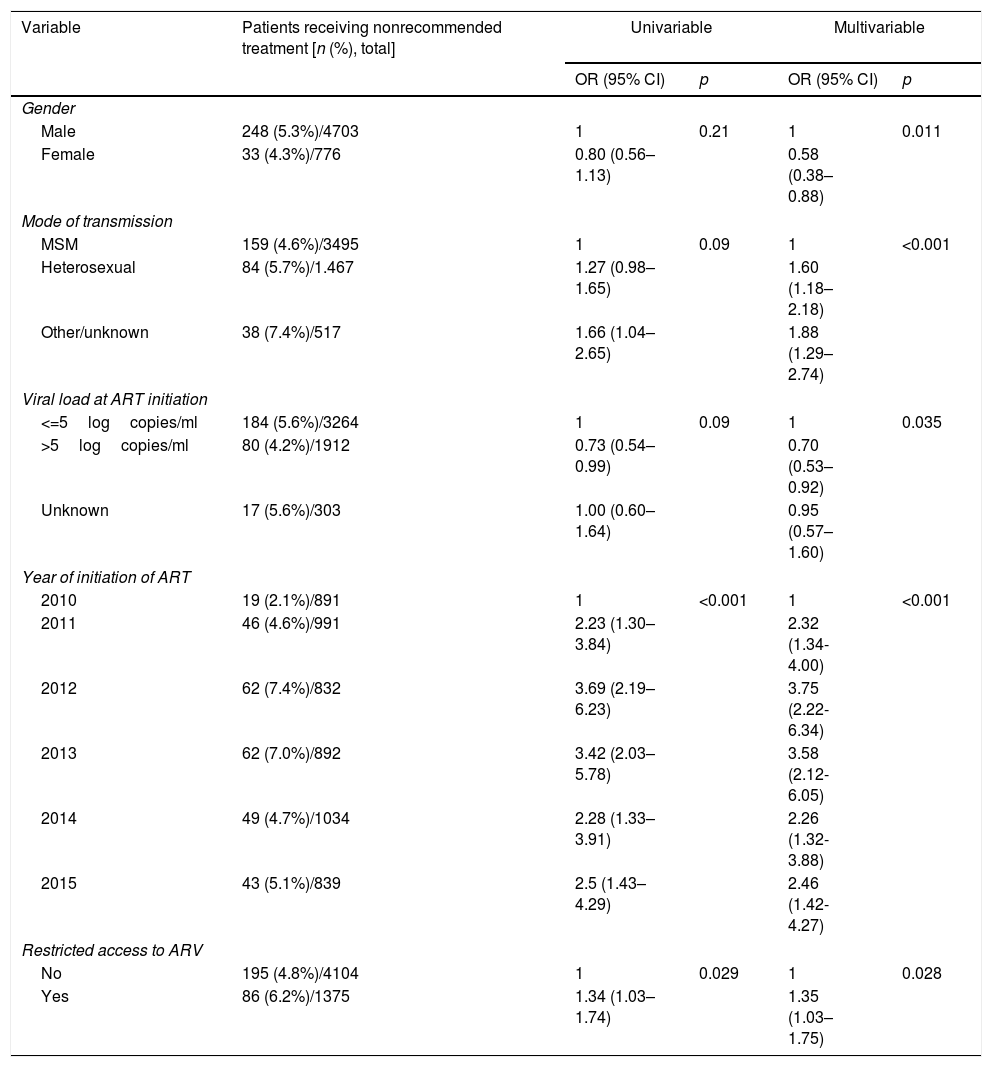

After considering patients enrolled in clinical trials and pregnant women as receiving preferred/alternative treatments, only 281 (5.1%) patients would have received a nonrecommended treatment. The factors associated with receiving a nonrecommended treatment in multivariable analysis are shown in Table 4. Male patients, those who acquired HIV by heterosexual transmission (compared to MSM), those with viral loads <=5logcopies/ml, those who started treatment during the years 2011–2015 (compared to 2010), and those who started treatment in a center with restricted access to at least one antiretroviral drug had a significantly higher risk of receiving a nonrecommended treatment (Table 4). We found no significant association of the prescription of a nonrecommended treatment with age at treatment initiation, geographic origin, level of education, CD4 cell count at treatment initiation, number of hospital beds, or cost limitation for ART after adjusting for other risk factors.

Factors associated with receiving a nonrecommended treatment.a

| Variable | Patients receiving nonrecommended treatment [n (%), total] | Univariable | Multivariable | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 248 (5.3%)/4703 | 1 | 0.21 | 1 | 0.011 |

| Female | 33 (4.3%)/776 | 0.80 (0.56–1.13) | 0.58 (0.38–0.88) | ||

| Mode of transmission | |||||

| MSM | 159 (4.6%)/3495 | 1 | 0.09 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Heterosexual | 84 (5.7%)/1.467 | 1.27 (0.98–1.65) | 1.60 (1.18–2.18) | ||

| Other/unknown | 38 (7.4%)/517 | 1.66 (1.04–2.65) | 1.88 (1.29–2.74) | ||

| Viral load at ART initiation | |||||

| <=5logcopies/ml | 184 (5.6%)/3264 | 1 | 0.09 | 1 | 0.035 |

| >5logcopies/ml | 80 (4.2%)/1912 | 0.73 (0.54–0.99) | 0.70 (0.53–0.92) | ||

| Unknown | 17 (5.6%)/303 | 1.00 (0.60–1.64) | 0.95 (0.57–1.60) | ||

| Year of initiation of ART | |||||

| 2010 | 19 (2.1%)/891 | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 |

| 2011 | 46 (4.6%)/991 | 2.23 (1.30–3.84) | 2.32 (1.34-4.00) | ||

| 2012 | 62 (7.4%)/832 | 3.69 (2.19–6.23) | 3.75 (2.22-6.34) | ||

| 2013 | 62 (7.0%)/892 | 3.42 (2.03–5.78) | 3.58 (2.12-6.05) | ||

| 2014 | 49 (4.7%)/1034 | 2.28 (1.33–3.91) | 2.26 (1.32-3.88) | ||

| 2015 | 43 (5.1%)/839 | 2.5 (1.43–4.29) | 2.46 (1.42-4.27) | ||

| Restricted access to ARV | |||||

| No | 195 (4.8%)/4104 | 1 | 0.029 | 1 | 0.028 |

| Yes | 86 (6.2%)/1375 | 1.34 (1.03–1.74) | 1.35 (1.03–1.75) | ||

The most frequently prescribed nonrecommended treatments were ABC+3TC+DRV/r (55 patients, 19.6% of all those receiving nonrecommended regimens), ABC+3TC+RPV (53 patients, 18.9%), and ABC+3TC+NVP (37 patients, 13.2%). The most frequent reasons for prescribing these regimens were cost (in 18.1%, 26.4%, and 51.3% of patients, respectively) and unknown (in 52.7%, 52.6%, and 35.1% of patients, respectively).

DiscussionIn this multicenter Spanish cohort, we have investigated the compliance to the national guidelines for the initial ART during the years 2010 and 2015, and we have explored factors associated with the prescription of nonrecommended treatments. As found in two previous studies in Spain in earlier periods,10,11 the compliance to the guidelines continues to be high in our cohort, and even higher (over 95%) if we consider patients enrolled in a clinical trial and pregnant women as receiving recommended or alternative treatments. This is a much higher proportion than the one found by a recent study in the United States, which described 16-21% of patients receiving nonrecommended treatments.24

Interestingly, there was a significant decrease in the prescription of preferred regimens in 2015, and a parallel increase in the alternative regimens, compared to the previous year. This was probably due to the more restrictive recommendations in 2015, when only integrase inhibitors and rilpivirine were considered preferred treatments and other regimens that had been recommended as preferred in 2014 (such as those including efavirenz or protease inhibitors) were classified as alternative. Clinicians were probably willing to continue prescribing regimens that were considered preferred until the year 2014 and with which they had extensive experience; also, regimens including efavirenz were considerably cheaper than those including integrase inhibitors or rilpivirine.25

The reasons provided by the prescribing physicians showed that almost half of the patients receiving nonrecommended treatments had been enrolled in clinical trials. After considering patients enrolled in clinical trials and pregnant women as receiving preferred or alternative treatments, the main reasons for prescribing nonrecommended treatments were comorbidities or interactions, as well as cost. We cannot exclude that a proportion of the nonrecommended treatments for which the reason for prescription was unknown could be really due to cost issues, as clinicians could be less willing to report that they made prescription decisions based on costs. More than half of the patients with nonrecommended treatments were receiving one of three regimens: ABC/3TC+DRV/r, ABC/3TC+RPV, and ABC/3TC+NVP. These regimens are cheaper than most of the preferred regimens25 and were not included in the guidelines due to insufficient evidence to support their efficacy as initial ART.3 According to the prescribing physicians, these regimens were frequently prescribed to lower the cost of ART.

It is worth noting that physicians reported prescribing nonrecommended regimens in a small subset of patients because of a “high viral load”. These patients received intensified regimens with four or five drugs between the years 2013–2015 in different centres and most were likely to have primary HIV infection. This has also been found in another French study,26 and it suggests that some clinicians still feel that high viral loads in primary infection need the prescription of additional drugs associated to the recommended regimens, despite the guideline recommendations and the evidence showing that these regimens are not more effective than three-drug treatments for primary infection.27

In multivariable analysis, prescription of nonrecommended treatments was significantly associated with male sex, heterosexual mode of transmission (compared to MSM), low viral loads and more recent years (compared to 2010). Prescription of recommended regimens has been found to be more frequent in patients with high viral loads in other studies,5,10 as clinicians are probably more likely to prescribe treatments which have demonstrated high efficacy to this group of patients. MSM were more likely to receive recommended treatments than heterosexual patients; this could be partly explained because MSM frequently have more access to information about HIV and could have more knowledge about new treatments than other patients.28

Due to restrictions in healthcare resources, the cost of ART has been limited in Spain by different means such as establishing a limit for the average annual cost for ART or restricting the prescription of certain antiretroviral drugs. To our knowledge, these constraints have not been studied previously. The limitations for the cost of ART, and restrictions for the prescription of certain antiretrovirals, affect a high proportion of patients (65% and 25%, respectively) and are unequally distributed across different centres and Autonomous Regions. This raises concern about inequalities in the access to ART, which may be dependent on the patient's place of residence and reference centre in a public healthcare system that is supposed to give equal access to treatment irrespective of the patient's place of residence.29

Our results suggest that the limitations for the prescription of antiretrovirals could influence the compliance to clinical guidelines, as the prescription of nonrecommended regimens was significantly higher in hospitals with restricted access to at least one antiretroviral drug. These hospitals were a heterogeneous group with restricted access to different recommended antiretrovirals, and most frequently newer integrase inhibitors which were preferred regimens during the later years of the study. However, prescription of nonrecommended regimens did not differ significantly between hospitals with and without cost limitations to ART.

The strengths of our study include a reasonably large number of patients from a multicenter, well established cohort; the recent time period that allows us to study the newer recommended regimens; the investigation of the reasons for noncompliance among the prescribing physicians (which has been previously assessed in only one study9); and the description of cost limitations for ART and their association with guideline compliance, which, to our knowledge, has not been previously described in Spain. The clinical and demographic characteristics of our patients are very similar to the ones of all new HIV diagnoses reported by the National HIV Surveillance System.30 Our limitations include a high proportion of unknown reasons for noncompliance, and lack on information on some potential factors influencing these reasons such as physicians’ experience.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, our results show a high proportion of initial antiretroviral treatments that comply with national guidelines in recent years in Spain. However, some groups of patients were more likely to receive treatments that were not recommended by the guidelines, such as male patients, those who acquired HIV by heterosexual transmission, those who had low viral loads and those who were treated in hospitals with restricted access to some antiretrovirals. Although we found a high proportion of centres with limitation of the cost of ART, guideline compliance seemed to have no significant association with these cost limitations.

FundingThe RIS cohort (CoRIS) is supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III through the Red Temática de Investigación Cooperativa en Sida (RD06/006, RD12/0017/0018 and RD16/0002/0006) as part of the Plan Nacional I+D+i and cofinanced by ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación and the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER)”.

AuthorshipAll authors were involved in the setting up of the cohort and contributed to its design. All authors were involved in data collection. ISG and IJ asked the research question presented in this paper and designed the study. IJ performed the statistical analyses. ISG wrote the first draft of the paper, which was supervised by IJ and SM. All authors were involved in interpretation of the data and commented on interim drafts. All authors have read and approved the final draft.

Conflict of interestAll authors declare that they have no conflict of interest related to this work.

This study would not have been possible without the collaboration of all patients, medical and nursery staff and data mangers who have taken part in the Project.

Executive committee: Santiago Moreno, Julia del Amo, David Dalmau, Maria Luisa Navarro, Maria Isabel González, Jose Luis Blanco, Federico Garcia, Rafael Rubio, Jose Antonio Iribarren, Félix Gutiérrez, Francesc Vidal, Juan Berenguer, Juan González.

Fieldwork, data management and analysis: Paz Sobrino, Victoria Hernando, Belén Alejos, Débora Álvarez, Inma Jarrín, Nieves Sanz, Cristina Moreno.

BioBanK HIV: M Ángeles Muñoz-Fernández, Isabel García-Merino, Coral Gómez Rico, Jorge Gallego de la Fuente y Almudena García Torre.

Participating centres:

Hospital General Universitario de Alicante (Alicante): Joaquín Portilla, Esperanza Merino, Sergio Reus, Vicente Boix, Livia Giner, Carmen Gadea, Irene Portilla, Maria Pampliega, Marcos Díez, Juan Carlos Rodríguez, Jose Sánchez-Payá.

Hospital Universitario de Canarias (San Cristobal de la Laguna): Juan Luis Gómez, Jehovana Hernández, María Remedios Alemán, María del Mar Alonso, María Inmaculada Hernández, Felicitas Díaz-Flores, Dácil García, Ricardo Pelazas., Ana López Lirola.

Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias (Oviedo): Victor Asensi, Eulalia Valle, José Antonio Cartón, Maria Eugenia Rivas Carmenado.

Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre (Madrid): Rafael Rubio, Federico Pulido, Otilia Bisbal, Asunción Hernando, Maria Lagarde, Mariano Matarranz, Lourdes Dominguez, Laura Bermejo, Mireia Santacreu.

Hospital Universitario de Donostia (Donostia-San Sebastián): José Antonio Iribarren, Julio Arrizabalaga, María José Aramburu, Xabier Camino, Francisco Rodríguez-Arrondo, Miguel Ángel von Wichmann, Lidia Pascual Tomé, Miguel Ángel Goenaga, Mª Jesús Bustinduy, Harkaitz Azkune Galparsoro, Maialen Ibarguren, Maitane Umerez.

Hospital General Universitario De Elche (Elche): Félix Gutiérrez, Mar Masiá, Sergio Padilla, Andrés Navarro, Fernando Montolio, Catalina Robledano, Joan Gregori Colomé, Araceli Adsuar, Rafael Pascual, Marta Fernández, Elena García., Jose Alberto García, Xavier Barber.

Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol (Can Ruti) (Badalona): Roberto Muga, Jordi Tor, Arantza Sanvisens.

Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón (Madrid): Juan Berenguer, Juan Carlos López Bernaldo de Quirós, Pilar Miralles, Isabel Gutiérrez, Margarita Ramírez, Belén Padilla, Paloma Gijón, Ana Carrero, Teresa Aldamiz-Echevarría, Francisco Tejerina, Francisco Jose Parras, Pascual Balsalobre, Cristina Diez.

Hospital Universitari de Tarragona Joan XXIII (Tarragona): Francesc Vidal, Joaquín Peraire, Consuelo Viladés, Sergio Veloso, Montserrat Vargas, Miguel López-Dupla, Montserrat Olona, Anna Rull, Esther Rodriguez-Gallego, Verónica Alba.

Hospital Universitario y Politécnico de La Fe (Valencia): Marta Montero Alonso, José López Aldeguer, Marino Blanes Juliá, Maria Tasias Pitarch, Iván Castro Hernández, Eva Calabuig Muñoz, Sandra Cuéllar Tovar, Miguel Salavert Lletí, Juan Fernández Navarro.

Hospital Universitario La Paz-Carlos III-Cantoblanco: Juan González-García, F Arnalich, José Ramón Arribas, José Ignacio Bernardino, Juan Miguel Castro, Luis Escosa, Pedro Herranz, Víctor Hontañón, Silvia García-Bujalance, Milagros García López-Hortelano, Alicia González-Baeza, María Luz Martín-Carbonero, Mario Mayoral, María José Mellado, Rafael Micán, Rocío Montejano, María Luisa Montes, Victoria Moreno, Ignacio Pérez-Valero, Berta Rodés, Talia Sainz, Elena Sendagorta, Natalia C Stella, Eulalia Valencia.

Hospital San Pedro Centro de Investigación Biomédica de La Rioja (CIBIR) (Logroño): José Ramón Blanco, José Antonio Oteo, Valvanera Ibarra, Luis Metola, Mercedes Sanz, Laura Pérez-Martínez.

Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet (Zaragoza): Ascensión Pascual, Carlos Ramos, Piedad Arazo, Desiré Gil.

Hospital Universitari MutuaTerrassa (Terrasa): David Dalmau, Angels Jaén, Montse Sanmartí, Mireia Cairó, Javier Martinez-Lacasa, Pablo Velli, Roser Font, Mariona Xercavins, Noemí Alonso.

Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra (Pamplona): María Rivero, Jesús Repáraz, María Gracia Ruiz de Alda, Carmen Irigoyen, María Jesús Arraiza.

Corporació Sanitària Parc Taulí (Sabadell): Ferrán Segura, María José Amengual, Gemma Navarro, Montserrat Sala, Manuel Cervantes, Valentín Pineda, Victor Segura, Marta Navarro, Esperanza Antón, Mª Merce Nogueras.

Hospital Universitario de La Princesa (Madrid): Ignacio de los Santos, Jesús Sanz Sanz, Ana Salas Aparicio, Cristina Sarriá Cepeda, Lucio Garcia-Fraile Fraile.

Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal (Madrid): Santiago Moreno, José Luis Casado, Fernando Dronda, Ana Moreno, María Jesús Pérez Elías, Cristina Gómez Ayerbe, Carolina Gutiérrez, Nadia Madrid, Santos del Campo Terrón, Paloma Martí, Uxua Ansa, Sergio Serrano, Maria Jesús Vivancos.

Hospital General Universitario Reina Sofía (Murcia): Alfredo Cano, Enrique Bernal, Ángeles Muñoz

Hospital Nuevo San Cecilio (Granada): Federico García, José Hernández, Alejandro Peña, Leopoldo Muñoz, Ana Belén Pérez, Marta Alvarez, Natalia Chueca, David Vinuesa, Jose Angel Fernández.

Centro Sanitario Sandoval (Madrid): Jorge Del Romero, Carmen Rodríguez, Teresa Puerta, Juan Carlos Carrió, Mar Vera, Juan Ballesteros.

Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago (Santiago de Compostela): Antonio Antela, Elena Losada.

Hospital Universitario Son Espases (Palma de Mallorca): Melchor Riera, Maria Peñaranda, Maria Leyes, Mª Angels Ribas, Antoni A Campins, Carmen Vidal, Francisco Fanjul, Javier Murillas, Francisco Homar.

Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria (Málaga): Jesús Santos, Manuel Márquez, Isabel Viciana, Rosario Palacios, Isabel Pérez, Carmen Maria González.

Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío (Sevilla): Pompeyo Viciana, Nuria Espinosa, Luis Fernando López-Cortés.

Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge (Hospitalet de Llobregat): Daniel Podzamczer, Elena Ferrer, Arkaitz Imaz, Juan Tiraboschi, Ana Silva, Maria Saumoy.

Hospital Universitario Valle de Hebrón (Barcelona): Esteban Ribera.

Hospital Costa del Sol (Marbella): Julián Olalla, Alfonso del Arco, Javier de la torre, José Luis Prada, José María García de Lomas Guerrero.

Hospital General Universitario Santa Lucía (Cartagena): Onofre Juan Martínez, Francisco Jesús Vera, Lorena Martínez, Josefina García, Begoña Alcaraz, Amaya Jimeno.

Complejo Hospitalario Universitario a Coruña (Chuac) (A Coruña): Eva Poveda, Berta Pernas, Álvaro Mena, Marta Grandal, Ángeles Castro, José D. Pedreira.

Hospital Universitario Basurto (Bilbao): Josefa Muñoz, Miren Zuriñe Zubero, Josu Mirena Baraia-Etxaburu, Sofía Ibarra, Oscar Ferrero, Josefina López de Munain, Mª Mar Cámara. Iñigo López, Mireia de la Peña.

Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca (El Palmar): Carlos Galera, Helena Albendin, Aurora Pérez, Asunción Iborra, Antonio Moreno, Maria Ángeles Campillo, Asunción Vidal.

Hospital de la Marina Baixa (La Vila Joiosa): Concha Amador, Francisco Pasquau, Javier Ena, Concha Benito, Vicenta Fenoll.

Hospital Universitario Infanta Sofia (San Sebastian de los Reyes): Inés Suárez-García, Eduardo Malmierca, Patricia González-Ruano, Dolores Martín Rodrigo.

Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén (Jaen): Mohamed Omar Mohamed-Balghata, Maria Amparo Gómez Vidal.

Hospital San Agustín (Avilés): Miguel Alberto de Zarraga.

Hospital Clínico San Carlos (Madrid): Vicente Estrada Pérez, Maria Jesus Téllez Molina, Jorge Vergas García, Elisa Pérez-Cecila Carrera.

Hospital Universitario Fundación Jiménez Díaz (Madrid): Miguel Górgolas, Alfonso Cabello, Beatriz Álvarez., Laura Prieto.

Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias (Alcalá de Henares): Jose Sanz Moreno, Alberto Arranz Caso, Julio de Miguel Prieto, Esperanza Casas García.

Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia (València): Maria Jose Galindo Puerto, Ramón Fernando Vilalta, Ana Ferrer Ribera.