Tularemia is a zoonotic disease caused by Francisella tularensis, a Gram-negative facultative intracellular coccobacillus1 with four recognized subspecies2: tularensis (type A), holarctica (type B), mediasiatica and novicida. Type A is found in North America, while type B is located, but not exclusively, in the northern hemisphere.3 In Spain, it was an uncommon disease until 1997, when the first tularemia outbreak occurred in Castilla y León.4 Until now, all cases reported in Spain were caused by F. tularensis subsp. holarctica. Clinical manifestations of tularemia fall into two main forms: ulceroglandular (>90% of cases in Europe)2 and typhoidal. However, there are three more clinical forms: oculoglandular, oropharyngeal/gastrointestinal and pneumonic.

We have previously published the first case of ulceroglandular tularemia in a non-endemic area (Asturias, Spain).5 Here, we present the first reported case of oculoglandular tularemia occurred in the same region which worried us.

An 88-year-old male presented to the emergency department of our hospital in April 2017 for diagnosis and management of pain in his right eye and the presence of conjunctival discharge. He did not have other symptoms, history of trauma, drug intake, or any recently local or systemic infection. His laboratory workup only showed a high value of C-reactive protein (5.5mg/dL) and his medical and surgical histories were noncontributory. A diagnostic of viral conjunctivitis was done and he was treated with lubricant and anti-inflammatory drops.

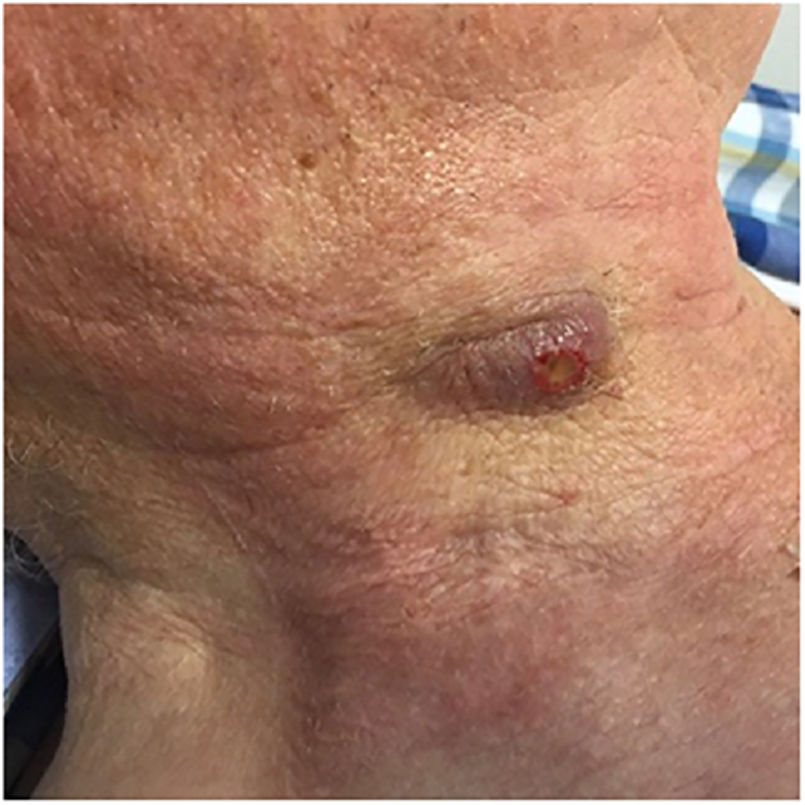

Two months later, he was brought to the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery with a painful cervical mass (Fig. 1), weight loss and discomfort. He did not declared a recent travel, contact to ill people or animals although he lives in a rural area. Clinical examination revealed the presence of a right neck mass measuring 30mm×20mm, with gummy consistency, painful on palpation and without other appreciable alterations.

A CT scan was performed and three neck lymph nodes together with an intraparotid lymph node were seen as pathological, showing necrotic areas.

A universal PCR was performed in fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB), based on amplification of the gene coding for 16S rRNA and subsequent sequencing (Bigdye® Terminator, Thermo Fisher Scientific). This evidenced the presence of F. tularensis subsp. holarctica. A second sample of FNAB was sent 10 days later resulting also positive.

In addition, serum samples were sent to the Spanish National Center for Microbiology (Madrid, Spain) in order to study the presence of antibodies against F. tularensis by microagglutination resulting positive with a titer of 1/1024.

Ziehl-Neelsen stain, culture and PCR for mycobacteria were negative. Lymphadenopathy-causing viruses (CMV, EB, HHV-6, HHV-7, HHV-8, Adenovirus, Picornavirus, Enterovirus, Mumps, LCMV) and Toxoplasma gondii were undetectable by PCR. Serological tests (ELISA) against Coxiella burnetii (IgG), Rickettsia conorii (IgG) and Borrelia burgdorferi (IgG/IgM) were negative.

Once the diagnosis was confirmed, the patient was treated with a 14-day course of intravenous streptomycin at a dose of 10mg/kg/12h, with favorable evolution. No surgical excision of the neck mass was needed.

Oculoglandular form of tularemia is very infrequent in our environment. In Spain some studies show an incidence of this form around 4%4 but this microorganism should be considered in a patient with Parinaud's syndrome even in non-endemic areas.

The gold standard for the diagnosis of tularemia is the isolation of the causative agent by culture, however, this is difficult (it requires a medium with cysteine) and hazardous for the laboratory staff (Biosafety Level 2 precautions). Therefore diagnosis is based mainly on serology and results became positive between 10 and 14 days after onset of the disease.6,7

Genome amplification by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is more sensitive than culture and provides rapid, sensitive and specific diagnosis of tularemia.8–10 There are specific targets of F. tularensis genes (e.g. fopA, tul4, ISFtu2 or RD1 protein-encoding gen) but when there is no suspicion of a specific etiological agent, it is useful to perform a universal PCR. In this case, if we had not performed the 16S rRNA PCR, the patient wouldn’t have been correctly diagnosed.

The present case shows the importance of molecular techniques that amplify panbacterial genes, especially useful for diagnosis of rare infections with great difficulty of isolation of the etiological agent like Bartonella henselae (also causing Parinaud's syndrome), Tropheryma whipplei, Borrelia spp. or Ehrlichia spp. Also in those cases without bacterial growth due to antibiotic treatment.

Financial disclosure and conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have not received funding to carry out this study and have no conflict of interests.