To describe the caring behavior of nurses at X Hospital in Indonesia as associated with their workload and the commitment of the nurses in providing nursing care. To be done by analyzing their workload over 24h.

MethodThe research design was observational analysis using a cross-sectional approach and conducted with 47 nurses who served in outpatient and inpatient units and were selected by a consecutive sampling technique. Each nurse was observed by using work sampling at 10-min intervals for 24h over 5 working days. The occupational commitment and nurses’ caring behavior were assessed with CNPI-23. This assessed the frequency with which nurses conducted nursing treatments that reflected caring behaviors.

ResultsObservational results indicated that nurses’ workloads have not yet reached heavy workload value (72.72% less than 80%) because nurses do more non-productive activities. This reduces the frequency with which the nurses conduct nursing treatments that reflect caring behavior, with a CNPI score of 54.62 (range score 23–115). The results showed that there is a relationship between workload and caring behavior through comfort care (p=0.03), and a correlation between occupational commitment and caring behavior through clinical care (p=0.01).

ConclusionCaring behavior is not fully reflected in the care given by nurses. The increased workloads and decreased commitment of nurses in achieving organizational goals can affect the caring behavior of nurses. This, in turn, will affect the patients’ satisfaction with the health service.

Caring behavior by nurses will not only focus on the physical needs but also on the mental, social, and spiritual needs of patients. Caring behavior in nursing is a therapeutic interaction between the patient and the nurse, which relates to the presence, affectionate touch, and the approach taken by the nurse in every nursing care situation. This involves evaluating the patient's emotions, providing information, and so fulfilling their needs that the healing process in the patient is facilitated.1–3 According to Gunther and Alligood, the attributes of the nurse should include empathy, commitment, and sincerity.2 According to Simon Roach, caring by nurses involves the “6Cs”, namely, compassion, competence, conscience, confidence, commitment, comportment, and creativity, all applied in each nursing care situation to all patients.4

Nurses who have a high level of commitment support the organizational goals. A high occupational commitment by nurses inspires them to work harder, and their productive, occupational commitment to the organization increases when their work expectations are met by the organization.5,6 Research resulting from several hospitals in Iran show a significant relationship between the commitment of nurses and their caring behavior (p=0.001).7 This is because occupational commitment influences the nurse's satisfaction and therefore the nurse's work. In an Indonesia hospital, nurses’ commitment was shown to have only a moderate relationship with their caring behavior (r=0.431; p=0.081).8

A lack of occupational commitment by nurses can ultimately harm an organization due to decreased performance and increased treatment costs resulting from patient dissatisfaction. Nurse dissatisfaction can also lead to increased turnover rates.9,10 In Spain, nurses’ job satisfaction has been related to time regulation and the workload of nurses.11 Nurse workload refers to the number of patient days worked, and the number of jobs or nursing time that burden nurse, both physically and non-physically, when providing nursing services to patients in hospital care.12 Nurse workload is also associated with the quality of the nursing service and with patient satisfaction.13 In 2017, patient satisfaction at X Hospital showed that approximately 20% of patients (545 out of 2717 inpatients) assessed nurses to be lacking in responsiveness when meeting the patients’ personal needs and lacking in empathy when providing nursing care.14 The purpose of this study is to describe the caring behavior that is associated with the occupational commitment of nurses in providing nursing care by analyzing the workload of nurses at hospital X over 24h. It is anticipated that the results obtained will be used to make recommendations to other hospitals in Indonesia, especially in relation to improving the quality of nursing services by implementing caring behavior in all nursing care.

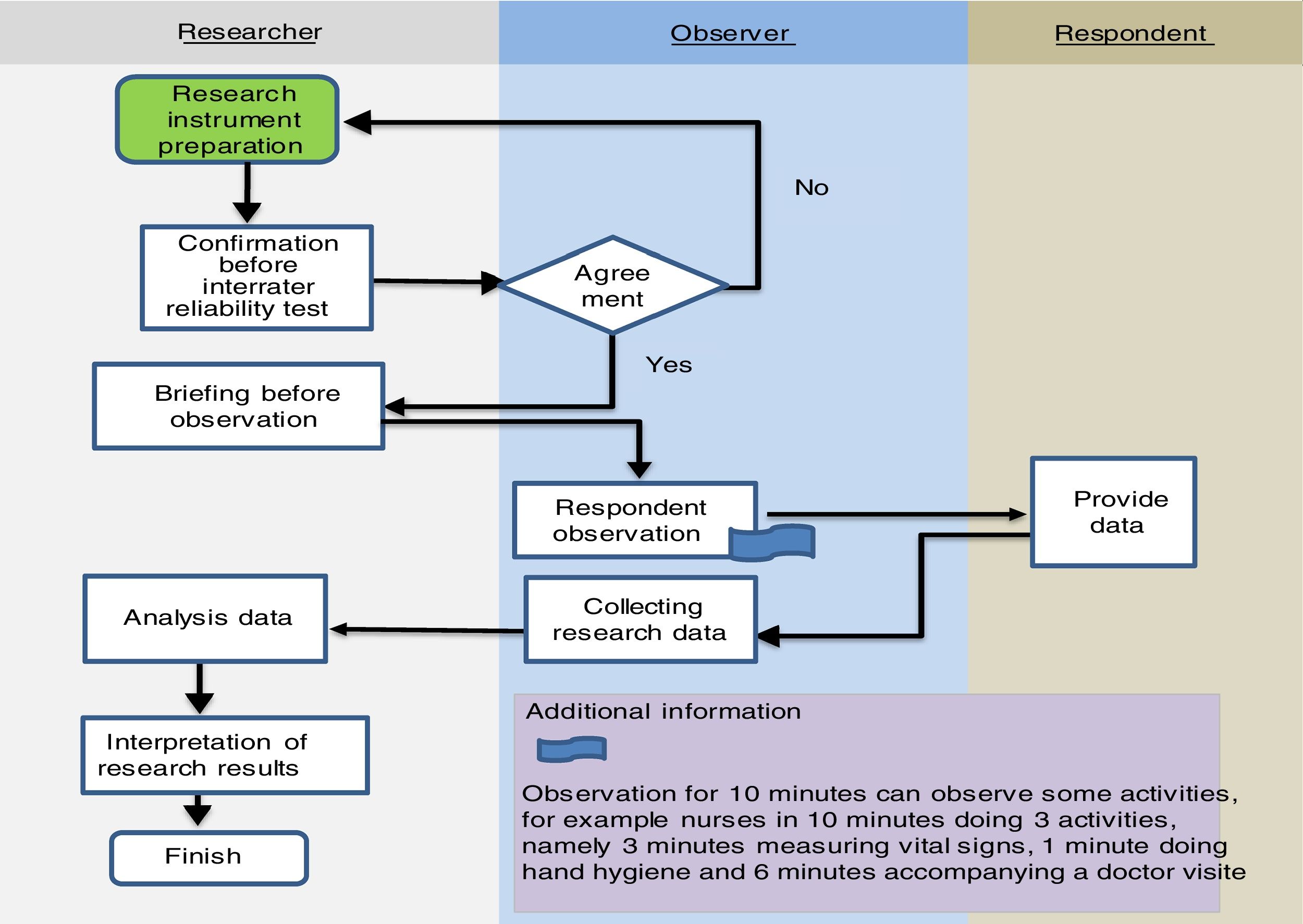

MethodsDesign, population, setting and sampleQuantitative research was conducted with an observational analytic design, using a cross-sectional approach. Forty-seven nurses from one hospital in Jakarta, Indonesia were selected by consecutive sampling and observed for 24h. The research flow is shown in Fig. 1. Inclusion criteria were nurses who served in either the inpatient or outpatient unit and were willing for their activities to be observed while they provided their regular nursing services.

Data collectionData were collected by using observation and through a questionnaire distributed to the nurses. Work sampling (WS) was used to get workload data, this involved observing the nurse every 5–10min during one shift and observing the time spent performing nursing activities, both productive and non-productive. WS was conducted for 24h for 7 working days with a time interval every 10min. To reduce the occurrence of observation bias, research data were taken on the third day of observation (observation for 5 working days), from 47 participants the observations were carried out for 5 working days with 10min of observation so that the results were 60 (min)/10 (min)×24 (h)×5 (working days)=720 observation samples. WS was conducted by research assistants who had passed the interrater reliability Cohen's Kappa test (K=0.73–1.00).

A benefit of WS observation is that it can assess the performance of a unit and determine the standard time for treatment.15,16 Nurse workload is calculated from the time used to perform activities in comparison with the total productive time on the total of nursing activities. The calculation results are in the form of percentages after multiplying by 100. The workload variable is presented with its mean value, standard deviation and confidence interval (CI) because the data is normally distributed (Table 1).

The nurses in the sample also filled in a questionnaire to provide the data on the respondents’ characteristics, occupational commitment, and their caring behaviors. The occupational commitment was measured by using the three components of the organizational commitment (TCM) questionnaire developed by Allen and Meyer. This was modified by adding two questions about the component of normative commitment. This instrument was validated and shown to be reliable with a Cronbach's Alpha of 0.821. The total number of questions was 18 and the total score was summed, and the results were then categorized as either high or low commitment.

Caring behavior was measured by using the Caring Nurse-Patient Interaction (CNPI), version 23, developed by Cossette et al., which had been translated into Indonesian.17 The CNPI was developed from the basic concept of transpersonal caring that assesses the behavior and attitudes of nurses based on the following aspects: frequency, competency, and feasibility.17 This study used the CNPI-23 to assess the caring behavior of the nurses based on the frequency of their providing nursing care and whether it was clinical, relational, humanistic or comfort care. The assessment of caring behavior was based on the frequency value in relation to the nurses’ workload analysis, which was based on the number of activities performed by the nurse during the observation period. Other aspects of caring behavior included in the CNPI-23 were not examined in this study. This questionnaire is valid and reliable with a Cronbach's Alpha value of 0.904. Caring behavior was assessed based on the CNPI's version 23 total score (score range 23–115), where the higher the CNPI score, the better the caring behavior.

Data analysisThe data were processed in two stages: descriptive statistics and bivariate analysis. The descriptive analysis included respondent characteristics, commitment, workload, and caring behavior. Bivariate analysis between the workload, age, and caring behavior was conducted using the Pearson correlation test. Bivariate analysis between occupational commitment, gender, level of education, period and work experience of was conducted using the independent t-test.

Ethical aspectsThis research was passed by the Faculty of Nursing Ethics Committee of Universitas Indonesia. This study applied the ethical principles of respect for human dignity, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice.

ResultsAn overview of the nurses’ workload in both the inpatient and outpatient units was obtained after 47 participants were observed in 3 shifts for 24h at 10-min intervals over five working days. Nurses in the outpatient units carried out the most activities with 15–18 activities in the 10min (for example: measuring blood pressure, with each activity taking 30–35s). In the inpatient unit, the nurses carried out, at the most, 3–4 activities in 10min. From 47 participants the observations were carried out for 5 working days with 10min of observation so that the results observation samples were carried out 1140 times, and 2010 activities were observed (1–18types of activities/10min). The differences between the results of each participant affect only the individual workload but do not affect the results of the overall workload analysis, because the WS method involved observing nurses for 24h for 5 days so that the results obtained represent the activities carried out by all nurses in inpatient and outpatient unit.

The results of the data analysis showed that the average workload of the nurses in this hospital was 72.72±12.04 with a workload varying between 69.18 and 76.25% (Table 1). The average amount of time spent on productive activities by the nurses in the hospitals was 254.94min, equivalent to 4.25h, and for more indirect nursing activities, it was 186.43min, or equivalent to 3.11h. Non-productive activities took up 86.74min and were the equivalent of 1.45h. Other duties as nurses or for organizational purposes were rarely carried out, and only took 13.35min or the equivalent of 0.22h (Table 2).

Workload analysis based on types of nursing activity in inpatient and outpatient unit of X Hospital, 2018 (n=47).

| Activities | Work unit | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Both units (n=47) | Inpatient (n=33) | Outpatient (n=14) | |

| Mean±SD (95% CI) | Mean±SD (95% CI) | Mean±SD (95% CI) | |

| Productive Nursing(min) | 254.94±117.84(220.34; 289.53) | 301.07±98.06(266.30; 335.85) | 162.32±148.10(76.81; 247.83) |

| Direct nursing(min) | 80.14±52.51(64.72; 95.55) | 104.41±43.24(89.08; 119.74) | 22.92±11.56(16.24; 29.59) |

| Indirect nursing(min) | 186.43±95.87(158.29; 214.58) | 196.66±62.75(174.41; 218.92) | 146.18±85.57(96.77; 195.59) |

| Nonproductive nursing(min) | 86.74±44.12(73.79; 99.70) | 74.59±26.72(65.11; 84.06) | 115.39±62.22)(79.46; 151.31) |

| Duty as a nurse(min) | 13.35±23.56(6.43; 20.26) | 3.25±2.43(2.39; 4.11) | 37.16±32.86(18.18; 56.13) |

| Personal(min) | 73.39±28.15(65.13; 81.66) | 71.34±25, 87(62.17; 80.51) | 78.23±33.47(58.90; 97.56) |

The proportion of nurses with low occupational commitment (51.10%) was slightly higher than nurses with high commitment (48.90%). Based on the components of the commitment variable, which include the affective commitment, continuance, and normative, affective commitment showed as the lowest compared with the continuous and normative commitment. The proportion of nurses who had low affective commitment was 55.30%. The results of this study also indicated that the nurses with high commitment had a lower workload (71.28±12.57) and a slightly lower caring behavior score (53.91±6.47) than nurses who had low commitment.

The results of the data analysis obtained a mean CNPI total score of 54.62±6.13. This value as compared to the total score (maximum CNPI−23 total score=115), only reached 47.5% or less than 50%, and it can be assumed that nurse caring behavior is relatively poor. The caring behavior analysis results showed caring behavior as based on four types. The average total score for caring in clinical care had a mean score of 22.83±2.33 or 50.73% of the maximum total score (5–45). Relational care had a mean score of 16.66±4.26 or 47.60% of the maximum total score (5–35), humanistic care had a score of 8.06±1.13 or 40.30% of the maximum total score (5–20), and comfort care had a mean score of 7.06±1.21 or 47.10% of the maximum total score (5–15).

Relationship between workload and nurse caring behaviorThe results of the analysis indicate that the strength of the relationship between workload and caring behavior was very weak and negatively correlated (r=−0.69). These results indicate that if the workload increases, the caring behavior will decrease. However, statistically, it shows that there was no relationship between workload and caring behavior (p=0.65). The type of caring behavior most associated with workload was comfort care (r=−0.32; p=0.03), meaning that the increased workload diminishes caring behavior in terms of patient comfort care.

Relationship between occupational commitment and nurse caring behaviorIn this study, CNPI scores for nurses with low commitment (55.29±5.83) were slightly higher than for those with high commitment (53.91±6.47). However, this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.45), so there was no significant relationship between occupational commitment and caring behavior. The significant difference in CNPI scores between low and high levels of commitment was seen in behavior in clinical care (p=0.01). The occupational commitment component showed no relationship with caring behavior (p>0.05).

DiscussionThe workload in nursing has three categories of care activities, namely care activities related directly to patients, care activities related indirectly to patients, and non-nursing activities related to the nurses’ personal needs.18,19 Results from the nurse workload analysis in the inpatient unit showed that the workload was within the optimum limit for someone working (80.90%). In the outpatient unit, it was below the standard of 80%, representing a low workload. The mean results of the productive activities analysis in the outpatient unit were lower than those in the inpatient (2.44h). Based on the assumptions of the researcher, this happens because the patients’ characteristics and nursing requirements in the two units are very different. For example, in the outpatients’ unit, there are shorter interactions times, the patients who enter are seldom in a state of emergency, requiring complex treatment, and the nurses depend more on collaborative treatment. All these factors limit the nursing treatment performed by nurses in outpatients. Outpatient units offer simple medical treatments that do not require hospitalization, and the nurses’ duties include measuring vital signs and the preparation of collaborative treatment tools.20

The analysis of the nurses’ workloads shows that they were lower than the optimum workload standard (80%), but, according to labor standards, they were still in the normal range of between 65 and 75%. These results indicate that nurses have enough time for their nursing activities even though the non-productive activities dominate. The correlation test results show that as the workload increased, the caring behavior of the nurses decreased. This could be due to the increased number of non-nursing activities so that nursing tasks directly relating to patients were not dealt with, with the result that caring behavior is requiring direct interaction with patients also decreased. One of the causes for not completing the main tasks of nursing was that there were non-nursing tasks that had to be completed, which became the nurses’ responsibility. If this occurred in an emergency it could cause patient dissatisfaction, and even death, and would be considered negligence.21–23

The overview of the nurses’ commitment showing low and high commitment did not show much difference on the basis of the occupational commitment component. The affective commitment was shown to be lower than the continuance and normative commitments. In general, nurses with a high level of affective commitment make a greater contribution to the organization as compared to nurses with a continuance or normative commitment. Effective commitment plays an important role in determining a person's behavior.24,25 Service quality is very dependent on occupational commitment (and especially affective commitment) so that the service provided by an organization will be undermined if the staff does not work willingly.9

The analysis of caring behavior in X Hospital suggests it is less than 50%, based on the maximum value of both the composite and the individual type of caring behavior. Previous research in several hospitals in Indonesia showed almost equal results, with fewer than 55% of nurses being perceived as showing low caring behavior.26,27 If caring behavior is not optimal, it can affect the quality of nursing care. Collaborative interactions between patients, nurses, families, other health teams, and even the community can be mutually beneficial, and if carried out continuously they can improve the quality of care and the health services.3,28

The workload of nurses in hospitals is still below the optimum value, with indirect nursing activities frequently being performed by nurses. The overview suggests that nurses’ occupational commitment is low. The affective component is the most important component in helping to achieve organizational goals, but this had the lowest value in this hospital. The overview of the nurses’ caring behavior, as taken from the CNPI for their total score, was still low when combined, with caring behavior related to clinical care having a higher average than the other CNPI total scores. This suggests that the caring behavior of nurses in this study is oriented toward clinical care and is not balanced in relation to the other types of caring.

In conclusion, caring behavior is still not fully reflected in every aspect of nursing care. The increased workload and decreased occupational commitment of nurses to achieving organizational goals can affect the caring behavior of nurses. This will have a negative impact on patient satisfaction with health services.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

This work is supported by Hibah PITTA 2018 funded by DRPM Universitas Indonesia No. 1848/UN2.R3.1/HKP.05.00/2018.

Peer-review under responsibility of the scientific committee of the Second International Nursing Scholar Congress (INSC 2018) of Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Indonesia. Full-text and the content of it is under responsibility of authors of the article.