Postpartum depression (PPD) is quite large, where there are 1 in 25 postpartum women experiencing PPD who still report symptoms of PPD after six months. The highest risk of experiencing PPD is more experienced by primiparas detected in 10–19 postpartum days. For PPD to not adversely affect the mother and baby, initial screening is needed to prevent the occurrence of PPD by using an Android-based EPDS application. The research objectives are an early screening of baby blues based on Android application and to determine the factors influence of baby blues. Participants download EPDS apps to make it easier for participants to screen the baby blues at the beginning of the first week after giving birth. On fourth week, the mothers refill EPDS apps screening to compare the results of screening the first week with fourth week using the Dependent T-test. In this study also analyzed the factors that influence the baby blues such as education, employment, parity, and age using the ANOVA Test. The study sample was the first-week postpartum mothers with a total sample of 64 people. The average EPDS screening results in the first week were 6.64, with a standard deviation of 2.57. The screening results on fourth week are 6.70, with a standard deviation of 2.53. The results of statistical tests obtained p-value 0.208; it can conclude that there was no difference in the results of screening tests in the first week with the fourth week. PPD events occur mostly in primiparas and women aged <20 years with p-value 0.001, while in education p-value 0.596 and employment-value 0.784. It recommended for pregnant women and health workers to do screening in the first week of postpartum so that it can detect PPD early.

Postpartum depression (PPD) is quite large, where there are 1 in 25 postpartum women experiencing PPD who still report symptoms of PPD after six months. The highest risk of having PPD is more experienced by primiparas detected in 10–19 postpartum days.1

Several studies that have examined the prevalence of PPD in developing countries show a prevalence of PPD of 10–20%. If not diagnosed or treated, PPD can hurt the mother and child, as well as the relationship between mother and child.2 Some mothers also feel uncomforted, pain, agony, and it cannot relive with any prescription. Almost all of them feel tired, weak, or stressed at any time after childbirth. Besides, it is frequently to be finding thatthey have a sleep disorder, and sometimes they not to sleep a wink.3

For PPD to not adversely affect the mother and baby, early screening is needed to prevent the occurrence of PPD. According to the study, Horowitz et al., there were 144 of 674 mothers who experienced the baby blues or mild baby blues using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) screening.4 EPDS is a method of screening to detect mothers who have PPD that can use after delivery.5

Postpartum women rarely get formal initial screening. Though mothers who get screened at 2–3 days postpartum will be able to predict PPD test results 4–6 weeks postpartum.1 EPDS helps predict postpartum depression, allowing initiation of secondary prevention efforts that focus on reducing the prevalence and duration of conditions.5

Based on Prasad research designed an electronic application called the Veedadom application designed to reduce depression, improve well-being in providing social support. Women who use this application can reduce potency depression.6

Through EPDS screening, researchers designed an Android-based EPDS application that can be used by the public, especially pregnant women and postpartum mothers to detect mothers experiencing postpartum depression. So with this application, mothers can do their screening and can reduce the impact of late screening. This screening application is called EPDS apps.

MethodologyParticipants download EPDS apps to make it easier for participants to screen the baby blues at the beginning of the first week after giving birth. Participants download the application and get instructions during the last week of their pregnancy, so they have time to enter the application and download the application on their cellphone. They were asked to use the baby blues screening application in the first week after giving birth. The mother herself will fill in the application-based screening, and after filling out, the application will issue the results of score information. On the fourth week, the mothers refill EPDS apps screening to compare the results of screening the first week with fourth week using the Dependent T-test. In this study also analyzed the factors that influence the baby blues such as education, employment, parity, and age using the ANOVA Test. The study samples were first-week postpartum mothers with a sample of 64 people.

ResultsThis study of baby blues screening had conducted in ±six months with EPDS application.

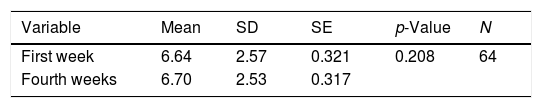

Comparison of EPDS screening in the first week with the fourth weekBased on Table 1, the average EPDS screening results in the first week were 6.64, with a standard deviation of 2.57. The screening results in the fourth week are 6.70, with a standard deviation of 2.53. The results of statistical tests obtained p-value 0.208; it can conclude that there was no difference in the results of screening tests in the first week with the fourth week.

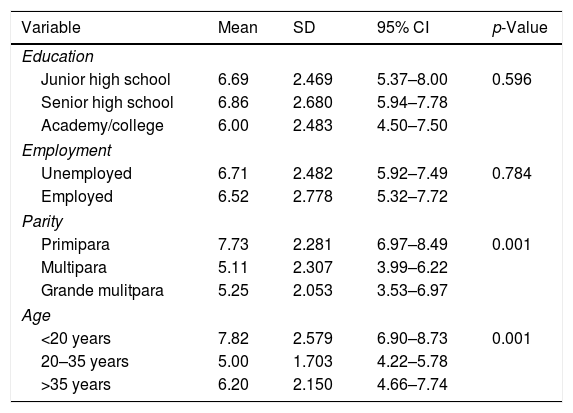

Factors influence of baby bluesBased on Table 2, The results of the statistical test obtained a p-value <0.05 are parity and age, the meaning there are differences in the results of screening based on parity levels and age levels. Education and employment have p-value >0.05, the meaning there are no differences in the results of screening based on education levels and employment levels.

The factors influence of baby blues.

| Variable | Mean | SD | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | ||||

| Junior high school | 6.69 | 2.469 | 5.37–8.00 | 0.596 |

| Senior high school | 6.86 | 2.680 | 5.94–7.78 | |

| Academy/college | 6.00 | 2.483 | 4.50–7.50 | |

| Employment | ||||

| Unemployed | 6.71 | 2.482 | 5.92–7.49 | 0.784 |

| Employed | 6.52 | 2.778 | 5.32–7.72 | |

| Parity | ||||

| Primipara | 7.73 | 2.281 | 6.97–8.49 | 0.001 |

| Multipara | 5.11 | 2.307 | 3.99–6.22 | |

| Grande mulitpara | 5.25 | 2.053 | 3.53–6.97 | |

| Age | ||||

| <20 years | 7.82 | 2.579 | 6.90–8.73 | 0.001 |

| 20–35 years | 5.00 | 1.703 | 4.22–5.78 | |

| >35 years | 6.20 | 2.150 | 4.66–7.74 | |

Based on Table 1, the average EPDS screening results in the first week were 6.64 with a standard deviation of 2.57. The screening results at week 4 are 6.70 with a standard deviation of 2.53. The results of statistical tests obtained p-value 0.208; it can conclude that there was no difference in the results of screening tests in the first week with the fourth week.

Postpartum assessment in the hospital does provide an opportunity to screen for risk factors associated with postpartum depression. A Canadian study recently found that the results of the Edinburgh Postnatal Screen Depression Scale (EPDS) screening were carried out 2–3 days after labor predicted postpartum depression at 4–6 weeks. When a cutoff of 10 points used, the sensitivity is 64%, and the specificity is 85% (using a repeat screen as standard). Ob/Gyn 6-week follow-up visits provide optimal opportunities for screening because they occur after two weeks that distinguish postpartum blues from postpartum depression and are agreements specifically focused on the well-being of the woman.7

Based on other research, states that screening and determining early diagnosis are very important. Early screening should be done at the time of pregnancy care and early after delivery. Symptoms of postpartum depression, such as the baby blues will be seen at ten days first and turn around 3–5 days.8

Generally, the symptoms of the baby blues do not interfere with the social function and work of women. Baby blues limit themselves without the requirements for active intervention except for social support and guarantees from family members. Baby blues can be associated with changes in female hormone levels, further aggravated by stress after giving birth. However, Baby blues that last for more than two weeks can make women vulnerable to more severe forms of mood disorders.9

Initial screening tests can be carried out during the pregnancy check-up period. Primary care visits during pregnancy can provide important opportunities for health education and detection of psychosocial risks. Usually, pregnant women and new parents are more likely to seek help in perinatal care settings than in special mental health settings and are often very motivated to modify their risk factors for the welfare of their children. The perinatal period can thus give doctors a unique opportunity to address the psychological and social aspects of their clients’ health and to address modifiable risk factors.10

Factors influence of baby bluesBased on Table 2, The results of the statistical test obtained a p-value <0.05 are parity and age, the meaning there are differences in the results of screening based on parity levels and age levels. Education and employment have p-value >0.05 the meaning there are no differences in the results of screening based on education levels and employment levels.

Based on other research showed that education status as many as 52 people (65%) respondents was highly educated, and 28 people (35%) respondents had low education. The incidence of postpartum blues most often found in respondents with high educational status, namely 21 people (40%) respondents, but most respondents who were low educated experienced postpartum blues, namely 16 people (57%) respondents from the total number of respondents who had low education, 28 respondents.11 Low education can result in limited knowledge, causing postpartum mothers to have negative perceptions and attitudes toward acceptance of unfavorable conditions. The other research which states that there is a tendency that the higher the level of education of women, the greater the likelihood of experiencing postpartum blues. Women who are highly educated face social pressure and role conflict between demands as highly educated women who have the urge to work and carry out outside activities and roles.9

Based on other research, it shows that the incidence of postpartum blues occurs in the majority of postpartum mothers who do not work or housewives 33 (30%) respondents. But the results of the analysis showed no significant effect between the risk factors for maternal employment status on the incidence of postpartum blues p-value 0.108. Based on research conducted,10 states that mothers who only work at home take care of their children can experience a state of a crisis and achieve feelings of disturbance/blues because of the fatigue and fatigue they feel. In a housewife who takes care of all her household affairs, it may have pressure on her responsibilities either as a wife or as a mother. The other research suggests that more female workers would return to the routine of working after childbirth and tended to have multiple roles that caused emotional disturbances.7 Women who work can experience postpartum blues due to multiple roles that responsibility these women. Women who work feel they have a greater responsibility in the household, namely as a wife and a mother who also has responsibility in her work.

Based on other research shows that the incidence of postpartum blues occurs mostly in primiparous mothers. The results showed that primiparous mothers had a 1.94 chance to experience postpartum blues compared to multiparous mothers.8 The primiparous woman just entered her role as a mother, but it did not rule out the possibility of a mother who had given birth, that is if the mother had a history of previous postpartum blues. Based on other research, the states that the birth of the first child shows stress and is associated with a stronger postpartum blues event than the birth of the second or third child. Primiparous women do not have experience in caring for children, resulting in fear and worry about making mistakes in caring for babies.12 Likewise, in carrying out duties as a mother, primiparous women feel confused, more burdened, and feel their freedom diminishes with the presence of a child. Postpartum blues events are often experienced by mothers who have given birth for the first time because this relates to the ability or experience of the mother in dealing with problems that occur in caring for the baby. Inexperienced mothers will have an impact on the care given to their babies. Mother's knowledge also has a major influence on the care done to her child.6

Based on other research shows that the majority of 88% of respondents aged less than 20 years experience postpartum blues.11 The results showed that there was a significant influence between the risk factors of maternal age on the incidence of postpartum blues, the age of postpartum mothers less than 20 years had a chance of 3.41 times to experience postpartum blues compared to postpartum mothers aged over 20 years.

The age factor of women during pregnancy and childbirth is often associated with women's mental readiness to become a mother. At an earlier age (teenage pregnancy) or further, it believed that it would increase biomedical risk, resulting in a pattern of behavior that is not optimal, both for mothers giving birth and for infants or children born and raised. It assumed that increasing maternal age would increase emotional maturity, thereby increasing involvement and satisfaction in the role of parents and forming optimal patterns of maternal behavior.10

ConclusionThe results of the study can be summarized as follows: there was no difference in the results of screening at the first postpartum week with the fourth-week postpartum, the incidence of PPD was mostly in primiparas and women aged <20 years. It is recommended for pregnant women and health workers to do screening in the first week of postpartum so that it can detect PPD early.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Peer-review under responsibility of the scientific committee of the 3rd International Conference on Healthcare and Allied Sciences (2019). Full-text and the content of it is under responsibility of authors of the article.