Self-stigma in people living with HIV/AIDS is a survival mechanism to protect themselves from external stigma. Stigma and discrimination in people living with HIV/AIDS can lead to inequality in social life. This inequality can cause inferiority complex, preoccupation, and denial of diagnosis, which correlates with the onset of depression. This study aims to determine the effect of logotherapy, commitment acceptance therapy, and family psychoeducation on self-stigma and depression on housewives living with HIV/AIDS.

MethodThis study used the quasi-experiment pretest–posttest design. The respondents were selected using the purposive sampling technique. The subjects were 60 housewives living with HIV/AIDS. Data were collected using Internalizes Stigma of AIDS Tools and analyzed using univariate and bivariate analyses. Equality analysis was conducted using the chi-square test and independent t test, and the effects were analyzed using paired t test.

ResultsThe result showed a significant decrease in self-stigma and depression (p value < 0.05) in patients receiving logotherapy, commitment acceptance therapy, and family psychoeducation.

ConclusionsA combination of logotherapy, commitment acceptance therapy, and family psychoeducation is recommended as a therapy package to overcome self-stigma and depression for people living with HIV/AIDS.

HIV/AIDS is among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in world1. It has become an epidemic in many countries because of its prevalence, and it is expected to increase in accordance with the increasing challenges faced by people living with HIV/AIDS.

The stigma that occurs in people living with HIV refers to the situation in which people living with HIV have a negative attitude against themselves and experience discriminatory actions from family, friends, and health services that lead to their embarrassment and negative self-image. Stigma and discrimination against people living with HIV can lead to inequalities in social life, thus making them unwilling to open themselves and socialize with the environment. This inequality increasingly inhibits HIV-positive people from functioning in their social environment2,3. Previous research suggested that the strong metamorphosis of HIV/AIDS has caused feelings of guilt and punishment for people with HIV/AIDS, especially for women. A woman is more likely to be blamed and considered as the source of infection than the husband even when the source of the infection is, in fact, her husband.

Depression is a common reaction that cannot be avoided, and it is the most frequent cause of psychiatric disorder in people living with HIV4. Research has shown that people living with HIV/AIDS are 20%-40% more likely to experience depression than the general population. Another study conducted in Nigeria on 122 people with HIV/AIDS showed that 21.3% of them experienced depression and 21.3% experienced depression limits5.

Treatment of HIV/AIDS does not focus only on the medical or physical aspect only but also on the psychosocial aspect, so that people living with HIV can adapt to grief, anxiety, and depression6. In addition to family, a support system or a main support system is also needed to enable people living with HIV to develop effective coping or responses. Accordingly, they will be able to adapt in handling the stressors related to their illness physically, psychologically, and socially and make them achieve psychological well-being.

Psychological well-being should receive special attention from people living with HIV (PLHIV) because if psychological well-being is not met, it will cause problems, such as social isolation, lack of social support, high level of stress, despair, and even self-injuring behavior7,8. Research has shown that the psychological welfare of people living with HIV can be improved through social support.

Family psychoeducation (FPE) is a mental health program that involves the participation of the family as a support system for the clients through the implementation of information and education using therapeutic communication. The purpose of this therapy is to improve the family's knowledge about the disease, identify the family problems associated with the treatment and care of family members suffering from HIV, and explore the potential strengths of the family in taking care of the sick family member. A study9 shows a decline in depression by 8.46% after being given acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) and FPE. The introduction of psychoeducation to a family whose member has HIV/AIDS can inform the family about the condition and symptoms, emotional state, treatment programs, medical aid, and steps to be taken to help people living with HIV face difficulties. Accordingly, PLHIV and families can respond positively in dealing with the problems they experience. A research conducted9 in Ciptomangunkusumo Hospital showed that conducting ACT and FPE on clients with HIV/ AIDS could reduce depression by 8.46%.

According to Vilardaga et al10, ACT is the behavioral therapy that can be used to treat complex clinical problems, such as depression and personality disorders. ACT uses several techniques that aim to teach positive psychological skills to the client. Logotherapy can be used by nurses to overcome the problem of negative perceptions about the effects of the disease and treatment. Logotherapy is existential psychotherapy that focuses on the awareness of the meaning of one's life as a way to achieve mental health. A research conducted by Widianti et al11 (2011) on adolescents who lived in the House of Detention and Prisons about the effect of logotherapy and supportive therapy showed a significant decrease in the level of anxiety and depression. Another study conducted on women with HIV/AIDS in India found that the use of logotherapy in the experimental group could significantly increase the life expectancy and that in the control increased thoughts of suicide.

The effect of self-stigma and depression on people with HIV/AIDS can make these people not adhere to the treatment program, thus lowering their quality of life. Moreover, it causes the non-optimal handling of stigma and depression in people living with HIV in Cirebon. Thus, this study examined the effect of logotherapy, ACT, and FPE on self-stigma and depression on housewives with HIV/AIDS.

MethodThis study used a quasi-experimental pretest–posttest design to determine the effect of an intervention, which is logotherapy, ACT, and FPE, on self-stigma and depression in housewives with HIV/AIDS. The research was conducted in the work area of Cirebon Regency's Health Agency and therefore the population in this study comprised housewives with HIV/AIDS. Sixty respondents were obtained using purpose sampling with some inclusion criteria and divided randomly into two groups (logotherapy group and ACT group). The instrument used in this study was Internalizes Stigma of AIDS Tools which included the characteristics of the respondents and items on depression, self-stigma, treatment compliance, and meaning of life. The data analyzed using paired t-test. Data collection was performed after the researchers explained in detail the procedures and processes to prospective respondents. The data collection was conducted after the respondents agreed and filled out the information consent form.

ResultsThe results revealed the characteristics of the respondents, their self-stigma, depression, treatment compliance, and meaning of life before therapy. Moreover, their self-stigma, depression, treatment compliance, and meaning of life were determined after logotherapy and then a combination of logotherapy, ACT, and FPE were given.

The characteristics of the respondents were as follows: average age was 32.5 years old, with the youngest at 20 and the oldest at 43; average length of time suffering from HIV was 1.99 years, with a range of 1-4 years; 38.3% of the respondents had an elementary educational background; 51.7% were employed; and 60% were married. Test results showed a p value> 0.05. Thus, the characteristics of the respondents were similar or homogeneous, as shown in Table 1.

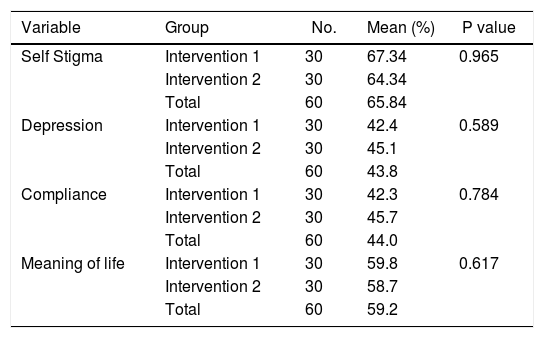

Analysis of self stigma, depression, compliance to treatment and meaning of life before intervention.

| Variable | Group | No. | Mean (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self Stigma | Intervention 1 | 30 | 67.34 | 0.965 |

| Intervention 2 | 30 | 64.34 | ||

| Total | 60 | 65.84 | ||

| Depression | Intervention 1 | 30 | 42.4 | 0.589 |

| Intervention 2 | 30 | 45.1 | ||

| Total | 60 | 43.8 | ||

| Compliance | Intervention 1 | 30 | 42.3 | 0.784 |

| Intervention 2 | 30 | 45.7 | ||

| Total | 60 | 44.0 | ||

| Meaning of life | Intervention 1 | 30 | 59.8 | 0.617 |

| Intervention 2 | 30 | 58.7 | ||

| Total | 60 | 59.2 |

Table 1 presents the analysis result of homogeneity of variance. The mean (p value) > 0.05 was considered significant. Thus, self-stigma, depression, treatment compliance, and meaning of life before intervention were equal or homogenous.

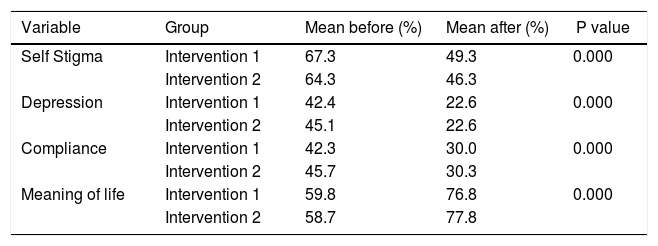

The changes in self-stigma, depression, treatment compliance, and meaning of life after logotherapy are shown in Table 2. In group intervention 1, a significant decrease in self-stigma at 18%, depression at 19.8%, and treatment compliance at 15.4% and an increase in meaning of life at 17% were observed after logotherapy.

Change in self stigma, depression, treatment compliance and meaning of life after logotherapy was given.

| Variable | Group | Mean before (%) | Mean after (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self Stigma | Intervention 1 | 67.3 | 49.3 | 0.000 |

| Intervention 2 | 64.3 | 46.3 | ||

| Depression | Intervention 1 | 42.4 | 22.6 | 0.000 |

| Intervention 2 | 45.1 | 22.6 | ||

| Compliance | Intervention 1 | 42.3 | 30.0 | 0.000 |

| Intervention 2 | 45.7 | 30.3 | ||

| Meaning of life | Intervention 1 | 59.8 | 76.8 | 0.000 |

| Intervention 2 | 58.7 | 77.8 |

In group intervention 2, a significant decrease in self-stigma at 18.1%, depression at 22.5%, and treatment compliance at 19.3% and an increase in meaning of life at 19.1% were observed after logotherapy.

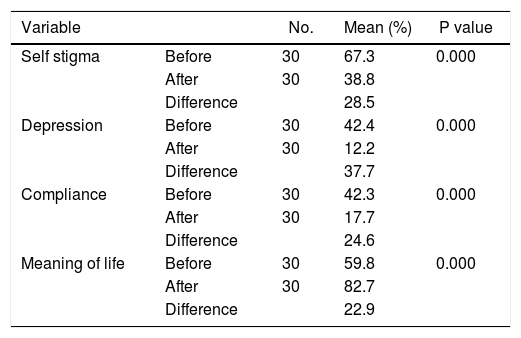

The changes in self-stigma, depression, treatment compliance, and meaning of life before and after logotherapy and ACT (group intervention 1) are presented in Table 3. In group intervention 1, a significant change in self-stigma at 28.5%, depression at 37.7%, treatment compliance at 24.6%, and meaning of life at 22.9% was observed after logotherapy and FPE.

Change inself stigma, depression, treatment compliance and meaning of lifebefore and after being given logotherapy and ACT (group intervention 1).

| Variable | No. | Mean (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self stigma | Before | 30 | 67.3 | 0.000 |

| After | 30 | 38.8 | ||

| Difference | 28.5 | |||

| Depression | Before | 30 | 42.4 | 0.000 |

| After | 30 | 12.2 | ||

| Difference | 37.7 | |||

| Compliance | Before | 30 | 42.3 | 0.000 |

| After | 30 | 17.7 | ||

| Difference | 24.6 | |||

| Meaning of life | Before | 30 | 59.8 | 0.000 |

| After | 30 | 82.7 | ||

| Difference | 22.9 |

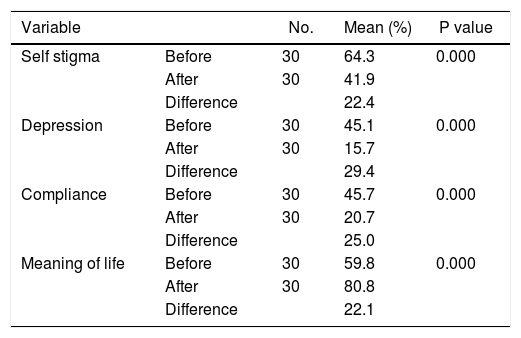

The changes in self-stigma, depression, treatment compliance, and meaning of life before and after logotherapy and FPE for group intervention 2 are presented in Table 4. In group intervention 2, a significant change in self-stigma at 22.4%, depression at 29.47%, treatment compliance at 25.0%, and meaning of life at 22.1% was observed after logo-therapy and FPE.

Change in self stigma, depression, compliance to treatment and meaning of life before and after being given logotherapy and FPE (group intervention 2).

| Variable | No. | Mean (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self stigma | Before | 30 | 64.3 | 0.000 |

| After | 30 | 41.9 | ||

| Difference | 22.4 | |||

| Depression | Before | 30 | 45.1 | 0.000 |

| After | 30 | 15.7 | ||

| Difference | 29.4 | |||

| Compliance | Before | 30 | 45.7 | 0.000 |

| After | 30 | 20.7 | ||

| Difference | 25.0 | |||

| Meaning of life | Before | 30 | 59.8 | 0.000 |

| After | 30 | 80.8 | ||

| Difference | 22.1 |

The changes in self-stigma in both groups after intervention were greater in group intervention 1 (logotherapy and ACT) with a decrease of 25.5% than in group intervention 2 (logotherapy and FPE) with a decrease of 22.4%.

Changes in depression were observed in both groups after the intervention, but a greater decrease was found in the group intervention 1 (logotherapy and ACT) at 29.9% than in the group intervention 2 (logotherapy and FPE) with a decrease of 29.4%.

Changes in treatment compliance were observed in both groups after the intervention, but a smaller decrease was found in the group intervention 1 (logotherapy and ACT) at 30.7% than in the group intervention 2 (logotherapy and FPE) with a decrease of 31.2%.

Changes in the meaning of life were observed in both groups after the intervention, but a greater increase was found in the group intervention 1 (logotherapy and ACT) at 22.9% than in the group intervention 2 (logotherapy and FPE) with an increase of 22.1%.

DiscussionThe self-stigma felt by housewives with HIV/AIDS before receiving logotherapy was considered high at 65.84%. This high percentage could be caused by the fact that they had never received treatment on self-stigma since they found out they were HIV positive. Moreover, they were afraid of disclosing their HIV status. This result is in consistent with the finding12 that self-stigma on people living with HIV can occur because of feelings of shame, fear of their status being known by others, and feelings of inferiority.

The self-stigma of housewives with HIV/AIDS decreased by 18% after being given logotherapy and by 10.54% after being given ACT (total of 28.54%). The combination of logotherapy and ACT lowered self-stigma significantly in the housewives with HIV/AIDS who participated in this study. They showed high enthusiasm in following the therapy proven by the fact that no one dropped out during therapy, and all the respondents were able to follow all the sessions in therapy.

ACT is a psychotherapy that aims to improve the psychological aspect, so that patients will have more flexibility or the ability to cope with changes better10. ACT uses the concepts of acceptance, awareness, and use of individual values to confront the internal stressor in the long term. Doing so can help individuals identify their thoughts and feelings, accept the changes that occur, and commit to themselves despite unpleasant experiences.

The depression felt by housewives with HIV/AIDS before receiving logotherapy was 43.78% and was considered moderate depression. It was caused by the fact that they had not received psychological treatment for their depressionrelated conditions since being declared HIV-positive.

Depression in people living with HIV is a reaction that cannot be avoided. The depression experienced by people living with HIV according to13,14 is a separate disease that should be treated because it can affect their ability to follow the treatment and reduce the quality of their lives. A study conducted in Nigeria on 122 people with HIV/AIDS showed that 21.3% experienced depression and 21.3% had depression limits5.

The treatment of depression in people living with HIV should be given special attention because of its effect, but treatment depends on the characteristics and symptoms of each individual14. Therefore, treatment of depression in people with HIV/AIDS requires time and should be effective.

Depression in housewives with HIV/AIDS decreased by 19.84% after being given logotherapy and by 9.96% after being given ACT (total of 29.80%). The combination of logo-therapy and ACT significantly reduced depression in housewives with HIV/AIDS as indicated by their high interest in the therapy. This interest is proved by the fact that none had dropped out during therapy and that logotherapy and ACT were new therapies and were different from voluntary counselling therapy counseling, which only emphasized screening and drug medication.

Depression in housewives with HIV/AIDS decreased by 22.54% after being given logotherapy and by 6.86% after being given FPE (total of 29.40%). The combination of logo-therapy and FPE could lower depression level significantly in housewives with HIV/AIDS. This finding is possible because family support is indispensable in people living with HIV/ AIDS in addressing various problems caused by their HIV-positive status. According to Lukens, FPE is a flexible psychotherapy that combines education and therapy techniques to treat people with medical, psychiatric, and other life problems. Moreover, the high interest in participating in therapy and the strong desire of respondents to overcome their grief caused by HIV make this therapy produce the expected results.

The researchers would like to thank to the experts in Psychiatric Nursing at the Nursing Faculty of UI, BPPDN, Head of Community Health Center, Indonesian Commission for Child Protection, non-government organizations, health cadres, our big family, friends, all the respondents, and other parties who supported this study.