The aim of this study was to examine prior studies relating to carers’ needs from mental health services for their own wellbeing.

MethodA systematic approach was adopted for the literature review. The databases searched included MEDLINE, PSycINFO, EMBASE, and CINAHL, involving the use of search terms such as carers, mental health, and needs. The search was conducted in April 2012 and updated in December 2015. In total, 40 published papers were included in the review and were subsequently assessed for quality. For the data synthesis, a thematic analysis approach was employed to integrate the quantitative and qualitative evidence relating to carers’ needs.

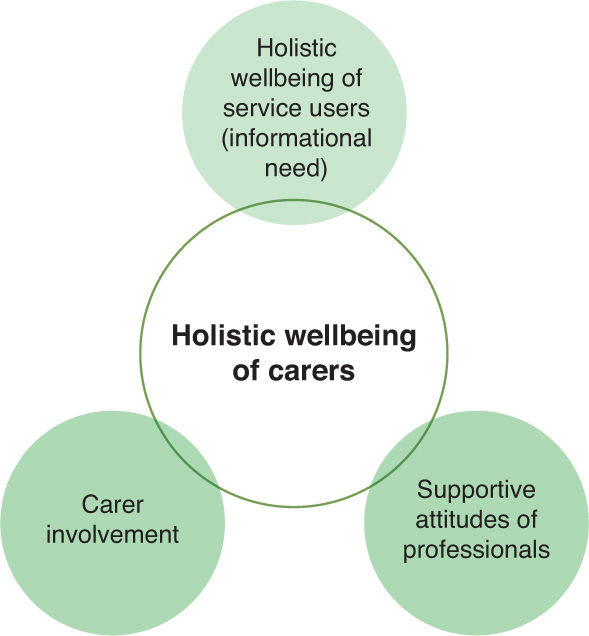

ResultsTwenty-five of the reviewed studies were qualitative, 12 were quantitative, and 3 were mixed. Four major carer needs emerged from the synthesis: (1) holistic wellbeing of service users, (2) holistic wellbeing of carers, (3) supportive attitudes of professionals, and (4) carer involvement. All four of these needs, in fact, revolved around the carers’ ill relatives.

ConclusionsThe studies reviewed suggest that while carers of people suffering from mental illness have a range of needs, they generally fail to offer straightforward information about their own needs.

Carers have been defined as people who deliver unpaid care to a family member or friend who needs support due to limitations of age, physical or learning disability, or illness1. Carers play a significant role in the treatment and support of relatives living with an illness, including those suffering from a mental health problem. In addition to providing practical help and personal care, carers give emotional support to mentally ill individuals2. It has been argued that without carers, the cost to the social health care budget in the UK would exceed £1.24 billion a year3.

It has been recognized that carers have specific needs owing to their caring role, including maintaining their own physical and mental health as well as receiving financial and practical assistance for supporting their caregiving duties4–6. For this reason, both the UK and Australian governments have acknowledged the roles of of carers and their right to receive appropriate support to care for their ill relatives7,8. There has also been recognition that more research is required to evaluate the benefits of support provision for carers and to explore whether health and social care services are meeting the needs of carers9,10. Numerous studies have been conducted to investigate carers’ needs, but reviews of the literature aimed at understanding their needs from mental health services have been scarce. Furthermore, there is inadequate literature suggesting what carers need in terms of ensuring their own wellbeing. This review was intended to address the following question: What does the literature suggest about the needs of carers from mental health services for their own wellbeing? More specifically, the objective was to search, identify, synthesize, and appraise the relevant studies on carers’ needs.

MethodA systematic approach was adopted to conduct the literature review. Such an approach offers a more rigorous synthesis method than a traditional review does. Systematic reviewers undertake activities to locate and synthesize research related to a particular question comprehensively, using organized, transparent, and replicable procedures at each step in the process11,12.

One of the principles employed in this review was limiting bias from the process of selecting the published research13. This involved using explicit, rigorous criteria for selecting the articles. These criteria enabled the researcher to ensure that only papers that were relevant to the research question were included in the review. Specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were determined prior to the commencement of the review. The inclusion criteria specified that the studies had to examine carers’ needs or expectations of mental health services; it had to be stated that the recipient of the care (service user) was experiencing a serious mental illness (i.e., long-term illness, such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorders, bipolar disorders, and chronic or persistent depression)14; the recipients of care (service users) had to be adults (over 18 years of age); the studies needed to employ qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods aimed at gathering data about carers’ needs; they had to be published in English; and the studies needed to have been published in the last two decades. The review excluded studies in which paid carers had been recruited as participants.

The search strategy involved the use of a number of search terms including carers, mental health, and needs. Synonyms were identified, such as need OR expectation; carers OR caregivers OR family. Truncation was also employed to detect a wide range of term endings, such as need*, to locate need and needs; and carer* for carer and carers. The search was conducted through MEDLINE, PSycINFO, EMBASE, and CINAHL.

The search was conducted in April 2012 and was updated in December 2015. The initial search yielded a total of 8,150 publications, and a title search excluded 7,644 papers. Abstracts of the remaining 506 papers were then retrieved. A further inspection of the abstracts excluded 381 papers. Full texts of the remaining 125 articles eliminated another 80 studies. The research team then discussed the 45 remaining papers. In total, 40 published papers were included in this review and were subsequently assessed for quality. A summary of the process as well as the reasons for exclusion are detailed in Figure 1 and Table 1.

Reasons for studies’ exclusion.

| Reasons for exclusion | Number of studies excluded | Number of studies retained (from 125 studies) |

|---|---|---|

| Involving older service users | 2 | 123 |

| Involving children service users | 7 | 116 |

| Not using carer participants | 3 | 113 |

| Using non-mental illness cases | 5 | 108 |

| Not yielding carers’ needs | 65 | 43 |

| Report paper | 3 Total: 80 excluded | 40 Total: 40 retained |

Further, detailed information was extracted on the characteristics of the participants, study settings, recruitment approaches, and data analysis methods (Appendix 1). The extraction procedure also involved summarizing all data in the included studies that were relevant to the review question (i.e., major findings relating to what carers need from services). The procedure continued to identifying whether the research yielded data on carers’ needs for their own wellbeing. This identification is important, as existing mental health services often disregard the carers’ interests and involve the carers only in speaking on behalf of their relatives’ wellbeing5. Discussions with the research team were conducted throughout the data extraction process until consensus was reached regarding the information retrieved. The summaries resulting from this extraction were helpful for synthesizing the reviewed studies.

A thematic analysis approach was adopted in the review to synthesize the data from the included studies15. The synthesis comprised two stages based upon the principles outlined by Thomas and Harden16, which offer a relatively clear and replicable process for addressing questions related to the participants’ perspectives.

The first stage was the development of descriptive themes, where free line-by-line coding was applied to the findings of the included studies. The coding was undertaken on extraction sheets to identify recurring themes surrounding carers’ needs from, and expectations of, mental health services. This procedure resulted in several categories of carer needs.

The second phase was developing analytical themes, where the previous descriptive themes were drawn to provide a new interpretation that went beyond the original studies. It involved collapsing some themes into another existing theme.

ResultsOf the 40 included papers, the majority concerned Western countries—the US, the UK, Australia, the Netherlands, Norway, Italy, Canada, Germany, and Sweden. Only 6 articles concerned non-Western countries—China, Taiwan, Japan, and South Africa.

Of these studies, 25 had samples of carers only, and 15 used mixed samples including carers and service users (n=7); carers, service users, and professionals (n=7); and carers and professionals (n=1). The total sample size of carer participants in all studies was 3,099. Samples of the carer participants varied from four carers in 2 studies17,18 and 746 carers19.

Twenty-five of the 40 studies were qualitative, 12 were quantitative, and 3 were mixed studies. Out of the 25 qualitative investigations, 16 did not report the specific methodology adopted. The remaining studies employed various methodologies, including grounded theory (n=3), content analysis (n=2), ethnography (n=2), case studies (n=2), and symbolic interactionism (n=1). In terms of the methods for collecting the qualitative data, 15 used individual interviews, 9 adopted focus groups, and 1 study examined written qualitative data from carer participants.

Of the 12 quantitative studies, all involved the use of surveys. Most of the 12 surveys used recognized instruments, such as the Educational Needs Questionnaire (ENQ), the Camberwell Assessment of Need Short Appraisal Schedule (CANSAS), the Family Assessment of Needs for Services (FANS), the Relatives’ Cardinal Needs Schedule (RCNS), Needs Assessment of Caregivers/Families questionnaire from Salford Mental Health Project 1985, the Friedrich-Lively Instrument to Assess the Impact of Schizophrenia on Siblings (FLIISS), the Degree of Congruence between Attributes of Home Care Services Desired and Received Questionnaire (DCAHCSDRQ), and a standardized Carer assessment by Gloucestershire Partnership NHS Trust (2003). Some modified/self-developed instruments were also used: Chinese Modified Educational Needs Questionnaire (CENQ), Italian version of Camberwell Assessment of Need (ICAN), and the Carers’ Needs Assessment for Schizophrenia (CAN-S). All of the three mixed studies also employed surveys for their quantitative investigations. For example, Jubb and Shanley20 and Lloyd and Carson21 posted written open-ended questions in a survey to obtain data for their mixed methods studies.

Relationships of the carer participants and their family members with a serious mental health problem were identified in 25 studies. Most of the carer participants were siblings (n=1,061), followed by parents (n=1,051), spouses/ partners (n=171), adult children (n=79), and others (n=47). Six studies used specific participants to investigate the needs of a specific group of carers, such as female carers, siblings, spouses, or parents.

The first stage of the synthesis (i.e., the development of descriptive themes) resulted in some categories of carer needs including informational, emotional, practical, and professional support. The need for information was dominant, and it was found in 32 of the 40 studies. This need focused on carers needing knowledge about mental health problems (e.g., signs, symptoms, and treatments), the progress of their relative with mental health problems, and the mental health services available. In addition, carers in 3 studies22–24 suggested that information should be individualized and tailored to the specific circumstances of each family and offered at an appropriate pace, particularly in the early stages of the mental health problem. Twenty-one studies revealed data outlining the need for emotional and practical support. Six studies uncovered the need for professional support and emphasized that carers wanted to be respected and listened to, and for health workers to demonstrate empathy. Finally, the need for carer involvement emerged in 9 of the 40 studies, specified as carers’ desire to be treated like part of the care team and, accordingly, be acknowledged as experts and consulted regarding decisions made for service users.

The similarities and differences between the categories were then identified and grouped into a hierarchical structure. Seven major themes including their sub-themes were revealed to describe what carers needed from healthcare services, as depicted in Table 2. Other similarities and differences were identified regarding the needs of carers across some cultures, described as Western (represented by carers living in North America, Europe, and Australia) and non-Western (represented by carers living in Asia and Africa). Several needs including needs for information, emotional support, supportive attitudes from professionals, and practical support were voiced in the studies in both Western and non-Western contexts. Nonetheless, while the carers’ needs for adequate wellbeing and involvement in the services were expressed profoundly in the US, Canada, and Europe, these needs did not emerge from the investigations with Asian and African subjects.

Themes from the descriptive stage of synthesizing the reviewed studies.

| No. | Main themes | Sub-themes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Information | • Method for giving information |

| • Content of the needed information | ||

| 2 | Emotional support | • Emotional support for other family members and friends |

| • Consultation with, or therapy from, professionals to express concerns associated with caregiving | ||

| • Involvement in support groups | ||

| • Spiritual support | ||

| 3 | Adequate wellbeing of service users | • Mental, physical, and social wellbeing |

| • Improving services for service users | ||

| 4 | Supportive attitudes of professionals | • Being respectful of carers |

| • Listening to carers | ||

| • Having empathy for carers | ||

| 5 | Carer involvement | • Carers as part of the care team |

| • Carers being consulted regarding decisions for service users | ||

| • Being acknowledged as experts | ||

| 6 | Adequate wellbeing of carers | • Emotional, physical, and social wellbeing |

| 7 | Practical help in performing caring role | • Respite care |

| • Practical help for daily life | ||

| • Practical help during a crisis | ||

| • Easy access to services | ||

| • Housing assistance | ||

| • Financial assistance | ||

| • Legal assistance |

The second stage of the synthesis (i.e., the development of analytical themes) involved an advanced interpretation of the original studies. It included collapsing some themes into another existing theme, as presented in the previous Table 2. To illustrate, the needs for information and emotional support were grouped under the theme of carers’ need for adequate wellbeing; ultimately, this theme was labelled as carers’ need for holistic wellbeing. In addition, this phase involved a re-examination of the data to ensure that the themes were represented. For example, the data related to improving services were re-examined and grouped together with the data of the need for practical support under a new theme: the need for the service users’ holistic wellbeing. The result at this stage was the identification of four major carer needs: (1) holistic wellbeing of service users, (2) holistic wellbeing of carers, (3) supportive attitudes of professionals, and (4) carer involvement. Further analysis resulted in the grouping of needs (1) holistic wellbeing of service users and (2) holistic wellbeing of carers, which were respectively closely associated with the wellbeing of service users and carers, and needs (3) supportive attitudes of professionals and (4) carer involvement, which have indirect connections to the wellbeing of carers or service users, as shown in Figure 2.

Finally, the synthesis could describe the relationship between the emerging themes. A deeper analysis of the data related to the needs for supportive attitudes of professionals (3) and carer involvement (4) suggested that these needs were voiced because the carers wanted their ill relatives to receive the best services. Likewise, many carers reported that they required information because they wanted to be more knowledgeable and skilled in caring for the service users. Therefore, it can be assumed that all four carer needs uncovered in this review were actually dedicated to the carers’ ill relatives, as illustrated in Figure 3.

DiscussionThe 40 studies reviewed suggest that carers have a range of needs. The findings from the qualitative studies were meaningful for their rich and thick descriptions of the needs, which augmented the data from the survey studies. However, several considerations should be taken into account before attempting to apply the findings in other contexts. First, the reviewed studies were mostly carried out in Western countries, such as the UK, the US, Australia, and the Netherlands, and these countries are culturally different from the non-Western countries represented (e.g., the country of origin of the first author was sometimes located in Asia). Investigations into carer needs in Asian countries were mostly conducted by administering surveys, which resulted in limitations in terms of their small sample size and response bias from the respondents. Moreover, Asian carers were only represented by participants from a Chinese cultural background. Only one Asian-based qualitative study was included in this review25, and it explored the experience of a homogeneous group of carers belonging to community family associations in Japan. As stated earlier, there was a significant gap between the needs of carers from Western and non-Western countries, especially relating to the views about carer involvement and carers’ wellbeing. In addition, the reviewed studies were mostly conducted in circumstances where the value of carers has been legally recognized, followed by substantial development of services for those with mental health problems. Consequently, the reported carer needs might have been different if the studies had been conducted in Indonesia, for example, where services for carers are less developed.

Second, the needs of carers revealed in this review were mainly related to the service users’ needs, such as improving/maintaining the service users’ health status. This does not mean that the carers’ own needs were not revealed. After following the data extraction and synthesis procedures, the researcher was eventually able to identify the carers’ needs for their own wellbeing. This identification was quite toiling because the reviewed studies failed to offer straightforward information about the carers’ own needs. This contradicts the existing perspective that carers and service users have very different needs5.

Regarding the data collection method, the studies employed varied approaches to elicit information about carers’ needs. These included surveys, in-depth individual interviews, and focus groups. When conducting surveys, asking carers to fill out survey might have numerous benefits, including minimizing costs, saving time, and involving large samples. Nevertheless, even with the assistance of reliable and valid surveys, such as the the Relatives’ Cardinal Needs Schedule (RCNS)26, the adoption of the instrument must be treated with caution when it is used in countries where English is not people's first language. The main issues of the current tools for investigating carer needs surround translation and the limited needs covered27. Moreover, as affirmed by some researchers, the survey method has several flaws that can also present issues in qualitative works, such as potential bias from the respondents and the researcher/ interviewers; inability to capture extensive, complex, and sensitive information; and the issue of social desirability23,26,28–31. Alternatively, most investigators in the reviewed studies favored qualitative methods, especially in-depth individual interviews and focus groups. As expected, the one-on-one dialogues and focus groups were able to elicit information about carers’ needs that was rich, deep, and extensive. Such methods allowed carers to express their needs in detail and sourced from their own experience of caring for ill family members32. Moreover, regarding focus groups, some investigators affirmed that this method was excellent for encouraging the carer participants to reflect on the stories of others when expressing their needs based on their contacts with services and experiences in caregiving33,34. The focus groups could also promote a safe environment for the carer and service user participants to discuss a topic that in other circumstances might be sensitive because of stigma, marginalization, or a lack of opportunity33.

This review provides a broad overview of what carers require from mental health services. The description given is comprehensive, sourced from qualitative and quantitative investigations undertaken in different regions of the world. However, there are several limitations to this review. First, publication bias might have been introduced, since the findings reflect data reported in academic journals, but do not represent unpublished literature, such as conference proceedings, theses and dissertations, and other grey literature. In addition, the review excluded non-English studies and studies published before 1990, which means that the review might have excluded some relevant studies.To summarize, this paper presented the results of a synthesis of what carers need from mental health services from the extant literature. Due to the limitations of the reviewed studies, the application of the evidence to other contexts, which are culturally different, can be problematic. Likewise, as the studies were mainly conducted in places where the caring role has been formally supported, the findings might be dissimilar if the needs of carers were explored in areas where services targeting them are underdeveloped.

Conflicts of interest| No | Authors | Country of Origin | Number of carer participants and relationship with service user | Setting | Recruitment of carer Participants | Data analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Glendy and Mackenzie (1998) | China | 8 carers (3 parents, 3 spouses, 2 siblings) | All aspects of mental health services | Not stated | Content analysis |

| 2 | Johnson (2000) | USA | 180 carers (70% parents 13% siblings, 6% spouses, 8% adult children) | All aspects of mental health services | Contacts with potential participants already involved in a project for carers | Not stated |

| 3 | Smith et al. (2001) | USA | 45 carers (23 spouses, 16 adult children) | Mental health hospital services | Not stated | Not stated |

| 4 | Domboos (2002) | USA | 76 carers (no information of the relationship with service user) | A wide range of mental health services | Postal invitation from researcher and gatekeepers (managers of support groups of carers) | Content analysis |

| 5 | Bowes and Wilkinson (2003) | UK | 4 carers ((no description of their relationships with service user) | Community mental health services | Used gatekeepers (professionals and leaders of community groups of carers) | Thematic analysis |

| 6 | Bollini et al. (2004) | Italy | 13 carers (no description for their relationships with service user) | Community mental health services | Used gatekeepers (psychiatrists of the service users) | Not stated |

| 7 | Rose et al. (2004) | USA | 31 carers (14 parents, 5 siblings, 4 children, 6 spouses, 2 others) | A wide range services | Used gatekeepers (professionals, leaders of community groups for carers and church services) | Content analysis in combination with thematic analysis |

| 8 | Lakeman (2008) | Australia | 86 carers (parents 59%, spouse 17%, siblings 9%, adult children 5%, and grandparent 1%, others 8%) | All aspects of mental health services | Dissemination of the study in carer meetings, postal and phone invitations | Content analysis |

| 9 | Askey et al. (2009) | UK | 22 Carers (No description for their relationships with service user) | All aspects of mental health services | Dissemination of the study in the local mental health services and carer support groups | Thematic analysis |

| 10 | Lyons et al. (2009) | UK | 57 carers of people with mental illnesses (No description for their relationships with service user) | Mental health crisis services | Postal invitation | Thematic analysis |

| 11 | Mavundla et al. (2009) | South Africa | 8 carers (5 mothers, one sister, one father, one wife). | Community mental health services | Contacts with potential participants in outpatients | Unspecified qualitative analysis |

| 12 | McAuliffe et al. (2009) | Australia | 31 carers (25 parents, 3 partners, 3 siblings) | All aspects of mental health services | Poster display, and used gatekeepers (staff of mental health services and carer support groups) | Thematic analysis |

| 13 | van der Voort et al. (2009) | Netherland | 15 carers (all spouses) | Community mental health services | Pamphlet display and contacts with potential participants in organisation of carers | Coding techniques by Strauss and Corbin |

| 14 | Nordby et al. (2010) | Norway | 18 carers (15 parents, 3 siblings) | Mental health hospitals services | Used gatekeepers (hospital staff) to contact service users to obtain consent from their carers | Content analysis |

| 15 | Thomas et al. (2010) | UK | 7 carers (No description for their relationships with service user) | 7 Community health services and 1 prison | Used gatekeepers (staff of mental health services and organisations of carers) | Not stated |

| 16 | Van de Bovenkamp and Trappenburg (2010) | Netherland | 18 carers (No description for their relationships with service user) | All aspects of mental health services | Contacts with potential participants involved in organisations of carers | Content analysis |

| 17 | Copeland and Helleman (2011) | USA | 8 mother carers of adult children with mental illnesses | A wide range of mental health services | Dissemination of the study in community groups of carers, and used gatekeepers (nurses and social workers) for recruiting potential participants in the hospitals | Coding techniques by Strauss and Corbin |

| 18 | Jonsson et al. (2011) | Sweden | 17 carers (7 mothers, 3 fathers, 1 child) | Mental health hospitals | Postal invitation, followed with phone contacts for further explanation | Content analysis |

| 19 | Weimand et al. (2011) | Norway | 216 carers (156 parents, 18 partners, 27 siblings, 10 adult children, 5 others) | All aspects of mental health services | Postal invitation | Content analysis |

| 20 | Hacketal et al. (2012) | USA | 7 carers (No description for their relationships with service user) | A community mental health centre | Not stated | Content analysis |

| 21 | McHugh et al. (2012) | Germany | 14 carers (all spouses) | Mental health hospitals | Not stated | Grounded theory analysis |

| 22 | McNeil (2013) | Canada | 4 carers (No description for their relationships with service user) | A mental health hospital | Not stated | Line by line coding, arranged into themes |

| 23 | Mizuno et al. (2013) | Japan | 11 female carers (8 parents, 3 siblings) | Community mental health services | Dissemination of the study in support groups of carers | Content analysis |

| 24 | White et al. (2013) | USA | 17 carers (all parents) | Assertive community treatment service (ACT) | Used gatekeepers (team leaders of ACT teams) | Content analysis |

| 25 | Wood et al. (2013 | ) UK | 9 carers (No description for their relationships with service user) | Mental health hospitals | Used gatekeepers (staff of services/organisations for carers) | Thematic analysis |

| 26 | Ascher-Svanum et al (1997) | USA | 197 carers, (40% mother=80,15% sister=30,15% father=30,9% brother=20) | A wide range mental health services | Postal invitation | 118 item survey questionnaire, the name of questionnaire was not specified |

| 27 | Gasque-Carter and Curlee (1999) | USA | 80 carers (28 parents, 26 siblings, 9 daughters/sons, 3 spouses, 5 kins and 9 others) | A mental hospital services | Not stated | Cross sectional questionnaire using 52 items and 2 open ended questions (developed by the researchers), questioned via telephone |

| 28 | Chien and Norman (2003) | China | 240 carers (no description their relationships with the service user) | All aspects in mental health services | Phone and face-to-face invitation | Cross sectional questionnaire using 45 items of Chinese Modified Educational Needs Questionnaire (CENQ) |

| 29 | Sung et al. (2004) | Taiwan | 100 carers (39% parents, 36% spouses) | All aspect s in mental health services | Used gatekeepers (nurses and physicians) | Cross sectional questionnaire using 45 items of Educational Needs Questionnaire (ENQ) |

| 30 | Cleary et al. (2005) | Australia | 50 carers (50% parents, 32% spouses, 16% girlfriend/ boyfriend/others) | All aspects of mental health services | Carers were recruited based on consent from the service users | Face-to-face interview using 3 open ended questions |

| 31 | Gregory et al. (2006) | UK | 36 carers (22 parents, 2 partners, 2 siblings, 2 friends) | Assertive community Services | Hospital professionals distributed questionnaires as a part of an assessment program for carers | A standardized Carer assessment by Gloucestershire Partnership NHS Trust (2003) |

| 32 | Tung and Beck (2007) | Taiwan | 75 carers (42 parents, 13 spouses 7 children, and 13 others) | Mental hospitals | Initiated with phone contacts, then face-to-face contacts for further information of the study | Cross sectional questionnaire of the Degree of Congruence between Attributes of Home Care Services Desired and Received Questionnaire (DCAHCSDRQ) to assess 19 attributes of carers unmet needs from services |

| 33 | Drapalski et al. (2008) | USA | 308 carers (234 parents, 28 siblings, 9 adult daughters/sons, 18 spouses, 10 others) | All aspects of mental health services in the community | Postal information to service users to obtain consent for carers’ participation | Cross sectional questionnaire using 16 items of FANS (Family Assessment of Needs for Services), via mails |

| 34 | Friedrich et al. (2008) | USA | 746 carers (all siblings) | All aspects in mental health services | Postal invitation, advertisement in newsletter, and used gatekeepers (leaders of carer support groups) | Cross sectional questionnaire using 19 items of Friedrich-Lively Instrument to Assess the Impact of Schizophrenia on Siblings (FLIISS) to rate the importance carer needs and mental health services |

| 35 | McPherson et al. (2008) | UK | 32 carers (no description their relationships with the service user) | Assertive Outreach team services | Not stated | Cross-sectional questionnaire using 22 items of CANSAS (Schedule Camberwell Assessment of Need Short Appraisal Schedule) |

| 36 | Absalom-Hornby et al. (2011) | UK | 18 carers (12 parents, 5 siblings, 1 other) | Forensic mental health services | Postal invitation | Cross sectional interview using 48 items of FQ (Family Questionnaire) and 14 items RCNS (Relatives Cardinals Needs Schedule), questioned via telephone |

| 37 | Lasalvia et al. (2012) | Italy | 120 carers (no description their relationships with the service user) | Community mental health services | Contacted service users to obtain permission for their carers | Cross sectional questionnaire using 22 items of the Italian version of Camberwell assessment of Need |

| 38 | Winefield, and Harvey (1994) | Australia | 121 carers (68.6% parents, 17.4% siblings, 7.4% spouses, 4.1% adult child | All aspects of mental health services | Face-to-face contacts with service users to obtain consent for carers’ participation | Structured interviews |

| 39 | Jubb and Shanley (2002) | Australia | 14 carers (no description of their relationships with the service user) | A mental hospital | Postal invitation | Cross sectional questionnaire of Needs Assessment of Caregivers/Families questionnaire from Salford Mental Health Project 1985, delivered via mails |

| 40 | Lloyd and Carson (2005) | UK | 40 carers who attended 3 support groups | Community mental health services | Postal invitation to complete survey questionnaires and direct contacts with carers in support group meetings | Questionnaire and discussion meetings |