The survival of children against disaster can be seen from their confidence in their ability (self-efficacy). Self-efficacy can help children to determine their ability against disaster as preparedness. The proper intervention to increase self-efficacy as a protective factor is a therapeutic group therapy. The aim of this research is to measure the increase of self-efficacy of school age children against earthquake and Tsunami through therapeutic group therapy.

MethodThis research used quasi-experimental design with pre-post-tests with control group. The sample involved in this study is 69 children, where 35 of them are in the experimental group while the rest 34 children are in the control group consisting of school children at the IV and V graders of elementary school.

ResultsThe result of the research showed that the self-efficacy of school children is improved significantly after being treated with therapeutic group therapy (p value < 0,05), those who were not treated with therapeutic group therapy have no significant improvement (p value > 0,05).

ConclusionsThis research is recommended to be conducted on school age children to improve their self-efficacy against disaster through health education.

Disaster is an event caused by either natural or human factors that is threatening, harmful, and destructive to human life and leads to loss of life, environmental damage, loss of material, and psychological impact1. It is explained that natural disaster, primarily earthquake and tsunami, has been the most common type of disaster over the past 50 years (83%). The impact of such disasters includes death, injury, and homelessness. Guha-Sapir et al2 state that the Asian continent has seen the highest occurrence of natural disasters (44.4%). Indonesia is the Asian country with the highest number of disasters over the past decade, one of which was the tsunami in 2004 that killed 250,000 people. Disaster preparedness is aimed primarily at groups vulnerable to disaster risks, most of whom are school-age children3.

Having a high level of confidence in self-ability (self-efficacy) with regard to facing disaster can improve children's readiness for the impact caused by earthquake and tsunami disasters. Self-efficacy is a protective factor in individuals, and it also becomes the target area of nursing intervention for disasters4.

Therapeutic group therapy (TGT) is an intervention that can improve the protective factor of self-efficacy. TGT is a group therapy conducted through giving stimulation on developmental according age. This therapy can be implemented by sharing experiences, helping each other in solving problems, and teaching methods of stress-control5.

MethodThe design of this study was quasi-experimental pre-and post-tests with a control group. Purposive sampling technique with some inclusion criteria was used to obtain 69 children from two elementary schools. Thirty-five children from School A were involved in the intervention group and 34 children from School B in the control group. To measure self-efficacy in school-age children, the Self-Efficacy Questionnaire for Children (SEQ-C) was used, and was modified and tested for its validity. The result showed that the questionnaire was valid (r score > r table). The reliability test shows a score of 0.824 for cognitive competence, 0.896 for social competence, and 0.755 for emotional competence. Afterward, the intervention group underwent TGT seven times at ±60-90 min for each session. The data collection was conducted after school, and the procedure and process were explained to potential respondents in detail. This study was conducted after the respondents filled out the informed consent. This study received ethic approval from the faculty of nursing, Universitas Indonesia.

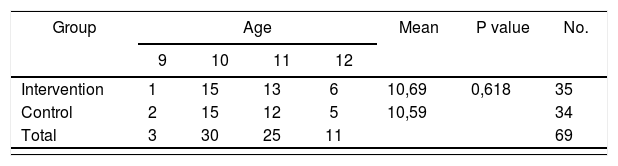

ResultsCharacteristics of ClientsThe results of this study show the value of central tendency on the variables of age, sex, and self-efficacy that can be seen in Table 1. The oldest of the respondents is 10 years old, and most of the respondents are male, with a self-efficacy score in the intervention group reaching to 56.94. After the analysis of statistical tests was conducted, the resulting score of p value > α = 0.05. The result concludes that there is no significant difference in the variables of age, gender, and self-efficacy of school-age children in the intervention group and the control group.

The distribution and analysis of equalities in age, gender, and self-efficacy of school age children (n = 69).

| Group | Age | Mean | P value | No. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | ||||

| Intervention | 1 | 15 | 13 | 6 | 10,69 | 0,618 | 35 |

| Control | 2 | 15 | 12 | 5 | 10,59 | 34 | |

| Total | 3 | 30 | 25 | 11 | 69 | ||

| Self-efficacy | Mean | P value | MD (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | 56.94 | 0.209 | −1.181;5.302 |

| Control | 54.88 |

| Gender | Mean | P value | MD (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | 62.19 | 0.734 | 0.558 (−2.709;3.826) |

| Control | 61.64 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; MD, mean difference.

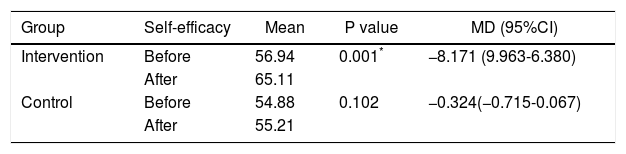

Improvement in self-efficacy of school-age children before and after participating in therapeutic group therapy can be seen in Table 2. Based on Table 2, it can be seen that the improvement in self-efficacy of school-age children before and after therapy is as much as 8.17 points. Further analysis obtains the score of p value: 0.001 < α = 0.05. This means there is a significant improvement in the self-efficacy of school-age children in the intervention group after being treated with the therapy. The control group, which is not treated with the therapy, shows no significant improvement, with the result of statistical test of p value: 0,102 > α = 0.05.

The analysis of self-efficacy difference before and after therapeutic group therapy implementation.

| Group | Self-efficacy | Mean | P value | MD (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Before | 56.94 | 0.001* | −8.171 (9.963-6.380) |

| After | 65.11 | |||

| Control | Before | 54.88 | 0.102 | −0.324(−0.715-0.067) |

| After | 55.21 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; MD, mean difference.

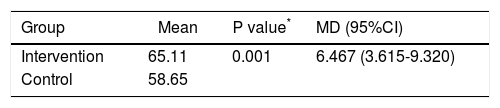

We can see the differences in self-efficacy improvement in this study in Table 3. Based on Table 3, it can be known that the average score of self-efficacy of school-age children on the intervention group is 65.11, while the control group is 58.65, with a difference of 6.467 points. Further analysis finds a significant difference between the intervention group after therapy treatment and the control group, resulting in a score of p value: 0.001 < α = 0.05.

The analysis of self-efficacy difference after therapeutic group therapy implementation on the intervention and control groups.

| Group | Mean | P value* | MD (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | 65.11 | 0.001 | 6.467 (3.615-9.320) |

| Control | 58.65 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; MD, mean difference.

Self-efficacy is the social-cognitive theory that determines how someone perceives, thinks, behaves, and motivates himself or herself. In the case of school-age children facing disaster, self-efficacy is needed as a coping or self-defense mechanism6.

The results of this study showed that the average score of respondents’ self-efficacy before receiving therapeutic group therapy was 56.94, or in the moderate range of self-efficacy in dealing with earthquake and tsunami disaster situations. After the therapy, this score increased to 65.11. The study also proved that there was a significant improvement in self-efficacy in children who underwent therapeutic group therapy (p value < 0.05).

The results of this study are in accordance with a theory by Towsend that explains that therapeutic group therapy is a therapy that not only helps individuals in enhancing their development, but also helps solve their problem and teaches stress and anxiety control when dealing with challenges or obstacles6.

In his study, Falls7 explains how group activities and discussion in the classroom can increase their ability to achieve their target or goal through learning from others during group activities. Students’ participation in the group activities affects self-efficacy through interaction, joint problem solving, and understanding in self-evaluation of their ability. Margolis and McCabe8 say that self-efficacy is a determining factor of the individuals’ motivation. Low self-efficacy is proved to trigger the emergence of difficulties in individuals’ academic achievements. In the long-term condition, low self-efficacy affects individuals by making them unable to accept failure and helplessness, which can be detrimental to the psyche.

Health education also plays a role in the improvement of protective factors in children, in this case facing earthquake and tsunami disasters. Stuart says that health education strategies serve as primary prevention methods through strengthening the individual and building their competence4. It is also explained that health promotion is effective in improving self-efficacy, which can be seen in improved behavior. Health promotion helps a person to understand their abilities, especially with regard to problem solving. Children need to understand every aspect of disasters with a high probability of occurring around them. Self-efficacy helps children gain confidence in their ability to deal with disaster. Self- efficacy will protect them and help them remain healthy and safe when disaster occurs. This is in line with the results of the study by Tian et al9 about the promotion and education of emergency situations in China after the earthquake in Wenchuan. This study found that promotion and health education has a significant relationship with knowledge, skills, and self-protective practices for earthquake victims. Other conclusions in the study explained that victims who have sufficient knowledge about earthquakes understand their self-ability (self-efficacy) about health and safety in dealing with an earthquake.

Bandura10 explains that self-efficacy is the key factor in changing behavior that influences motivations, actions, and prosperity. Although both treatments in this study provided increased self-efficacy in school-age children, the test results showed that therapeutic group therapy provided a more significant change and also significantly increased self-efficacy in dealing with earthquake and tsunami disasters. Children, as a vulnerable group with regard to disaster impact, are expected to know their self-ability as the preparedness in dealing with disaster. In another experiment by Nuranda et al11, they explain that group therapy and self-efficacy have an effect on children's preparedness to deal with earthquakes. The group therapy teaches children how to know their ability and preparedness in facing earthquakes by comparing and learning from each other.

Another study by Hamill12 revealed that self-efficacy is a belief relates to a child's competence in dealing with adversity. Thus, the self-efficacy intervention can contribute to how the children act, feel, and deal with the disaster. This is also emphasized by Chodkiewicz and Gruszczyńska13 research on changes in self-efficacy, coping strategies, and prosperity, in which he explains that those three aspects are factors in determining the degree of a person's depression.

Earthquakes and tsunamis potentially occur without notice. This situation then renders children to deal with an experience that affects them cognitively, socially, emotionally, and behaviorally. The theory of child development explains that children are considered as individuals who are at a certain stage of development. Cosario in Speier stated that children begin to develop their own ability in dealing with stress or challenges14 Speier also explains that the children will show signs of the stress-causing event through cognitive, emotional, physical, and behavioral dimensions14.

According to the results of this study, TGT can provide a change of perception and behavior. Therefore, TGT needs to be applied due to its ability to increase self-efficacy in children. High self-efficacy can also help improve children's preparedness in dealing with earthquake and tsunami disasters.