The objective of this study was to examine the experiences of violent incidents by nurses in Indonesian emergency departments.

MethodThe World Health Organization's structured questionnaire on workplace violence in the health sector was modified and translated into Bahasa. The study participants were 169 nurses working in emergency departments in six hospitals in Jakarta and Bekasi, Indonesia. The gathered data were analyzed using descriptive and multivariate logistic regression.

ResultsTen percent of emergency nurses reported experiencing physical violence, perpetrated mostly by patients, whereas more than half of emergency nurses (54.6%) reported experiencing non-physical violence, with patients’ relative as the main perpetrators. A majority of nurses (55.6%) did not have encouragement to report workplace violence, and very few nurses (10.1%) had received any information or training about workplace violence.

ConclusionsThe findings of this study highlighted the seriousness of violence in Indonesian emergency departments. Support from management, encouragement to report violence, and access to workplace violence training were expected to mitigate and manage violence against nurses in emergency departments.

Workplace violence in health care settings is a serious problem worldwide. The International Labor Office (ILO), International Council of Nurses (ICN), World Health Organization (WHO), and Public Services International (PSI) (2002) defined workplace violence as the use of physical or non-physical power against another person or group that could harm the victim physically, mentally, spiritually, sexually, morally, or socially. Among health care providers, nurses are at higher risk of victimization by violence. Previous studies in several countries indicated that 50% of nurses have experienced violent incidents (Gacki-Smith et al., 2009; Lin & Liu, 2005; Pai & Lee, 2011; Pinar & Ucmak, 2010; Esmaeilpour et al., 2010), with verbal abuse the most common type of violence.

Nurses working in particular areas in health care settings are more vulnerable to experiencing violence incidents. These areas include psychiatric departments, long-term care departments, intensive care units, and other high-risk areas in emergency departments (Peek-Asa et al., 2009; Barnes, 2011; Howell, 2011; Gacki-Smith et al., 2009). Highly stressful environments, 24-hour access, and an absence of security guards are factors that make emergency departments at higher risk of violent incidents (Howell, 2011; Gacki-Smith et al., 2009). Therefore, most nurses do not feel safe at all times while working in emergency departments (Pinar & Ucmak, 2010). Furthermore, aggression in emergency departments can negatively impact nurses and health care services.

Emergency departments are the entry point for health care services at hospitals, so violence in emergency departments can be very disruptive and threaten the image of health care services. Furthermore, violence can negatively impact emergency nurses’ personal and professional lives, as well as the quality of care they provide. Nurses report moderate levels of anxiety, intrusion, avoidance, hyperarousal, anger, and suffering post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms after experiencing violence (Gates et al., 2011; Pai & Lee, 2011). Regarding the quality of care nurses provide, violence decreases their productivity, changes their relationships with co-workers, and leads them to leave the profession (Gates et al., 2011). Nurses’ decision to leave the profession, moreover, can place a great burden on health care services, reducing the availability of health care services and increasing health care costs (ILO, ICN, WHO, and PSI, 2002). Therefore, interventions are needed to create safer working environments in emergency departments in Indonesia.

Appropriate interventions nevertheless depend on the particular characteristics of violence in each country. Regarding perpetrators of violence, for example, the most common sources of violence committed against nurses in several countries including the United States, Taiwan, and Australia are patients, followed by patients’ relatives and co-workers (physicians, supervisors, managers, and others who work with nurses) (Lin & Liu, 2005; Gacki-Smith et al., 2009; Findorff et al., 2005). Patients’ relatives, in contrast, are the primary perpetrators of violence against nurses in Middle Eastern countries, such as Turkey and Iran (Esmaeilpour et al., 2010; Pinar & Ucmak, 2010). These studies revealed that violence in emergency departments is a universal issue, but its local characteristics may vary across countries. In Indonesia, data on violent incidents experienced by nurses in emergency departments is not available. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine violent incidents experienced by nurses in Indonesian emergency departments.

MethodDesign and samplingThis study used a cross-sectional, descriptive design and convenience sampling. The inclusion criteria were registered nurses who were working full time and had at least three months’ experience in emergency departments. The estimated sample size was calculated using G*Power software version 3.1 based on the assumption of a =0.05, effect size = 0.15, power = 0.8 (Cohen, 1992), and 14 predictors. The sample size was over-sampled by 20%, anticipating missing data based on the response rate from the pilot study (100%) and other studies whose settings were emergency departments (77.9% to 94.8%) (Esmaeilpour et al., 2010; Pai & Lee, 2011). Thus, the minimum sample size was 162 nurses. Invitations to participate in this study were sent to 245 nurses in the emergency departments of six hospitals in Jakarta and Bekasi, Indonesia, and 169 returned the questionnaire for a response rate of 68.9%.

InstrumentsThe questionnaire used in this study was the Workplace Violence in the Health Sector Country Case Study Questionnaires (WPVHS). The WPVHS was first cooperatively developed by the ILO, the ICN, WHO, and the PSI (2003) regarding workplace violence in the health sector. The WHO granted permission to use the questionnaire in this study. The original English version of the questionnaire was modified and translated into Bahasa (WPVHS_B). The content validity index for scales (S-CVI) of this questionnaire was .88, and the mean of item CVI (I-CVI) was .96. The WPVHS_B was pilot tested for readability and preliminary psychometric properties. Twenty-one emergency nurses with at least three months’ experience working in emergency departments in public or central-governments hospital in Jakarta, Indonesia, were recruited. The results for two-week testretest reliability show kappa coefficients of 1.00 for physical violence and .72 for non-physical violence variable. The modified questionnaire had five parts.

ProceduresApproval from the Health Research Ethics committee, Faculty of Medicine University of Indonesia, Cipto Mangunkusumo Hospital, was obtained before the study. Permission to conduct the study was also secured from six hospital managers and head nurses in each emergency department. The researcher explained the procedures and relevant information about the questionnaire at regular nursing meetings. Nurses willing to participate in the study were asked to sign an informed consent form. A data collector was designated for each hospital and trained to provide information to the nurses if the researcher was unavailable. The researcher's contact information was also provided so that the participants could ask questions. The data collectors ensured that detailed information was provided to the participants and reported any questions to the researcher. Completed questionnaires were collected within one to two weeks. To achieve the best response rate, the researcher contacted the data collectors twice a week and asked them to remind the participants.

Statistical analysisAll the questionnaires were checked for missing data. All data were input into SPSS Statistical Package version 18 for coding and scoring and were checked for accuracy. Descriptive statistics were computed for all the variables. Means ± standard deviations, and percentages were used to describe the type and frequency of violence experienced by nurses in Indonesian emergency departments. Statistical significance was set at α < 0.05. The responses to the open-ended questions were analyzed using content analysis.

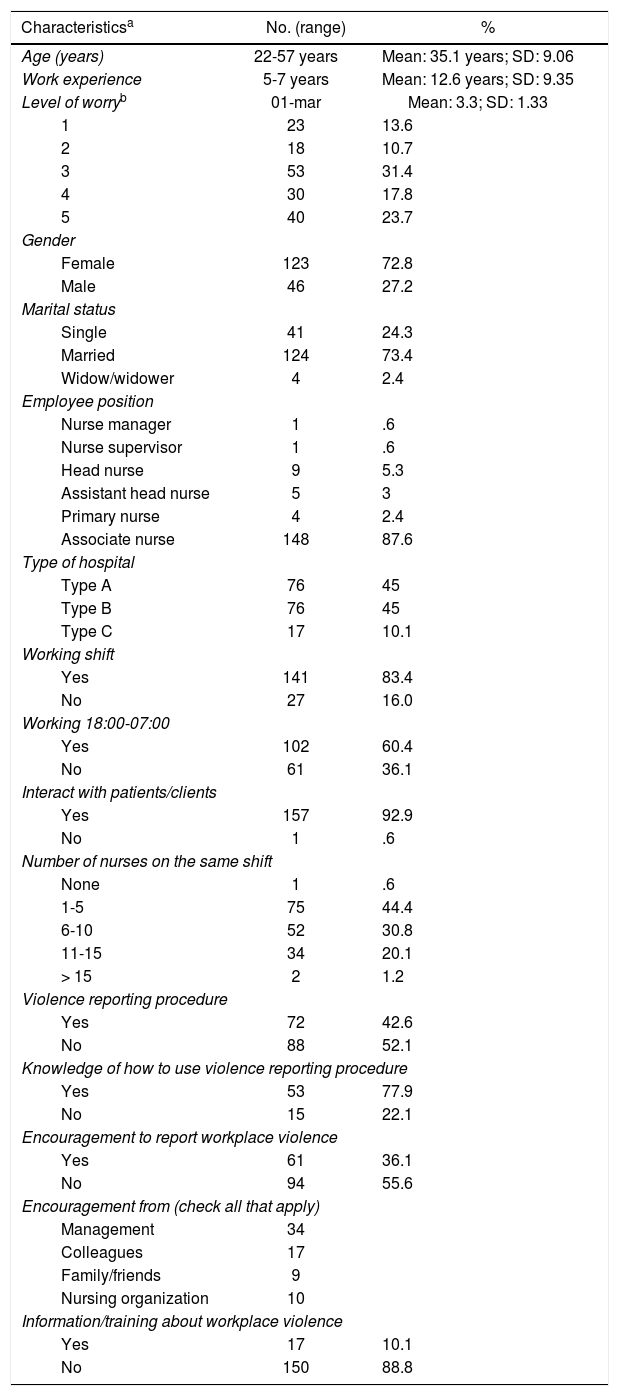

ResultsPersonal and workplace characteristicsTable 1 describes the personal and workplace characteristics of the participants. Most nurses who participated in the study were associate nurses (n = 148, 87.6%), followed by head nurses (n = 9; 5.3%); consequently, most participants worked in shifts (n = 141, 83.4%). Three-fourths of the participants (n = 128; 75.8%) indicated that the number of nurses who worked on the same shift varied (0-10 nurses). Type A hospitals, which were the biggest hospitals, provided a variety of health care services and had more nurses than both type B and C hospitals. The number of nurses who worried about violence in emergency departments was higher than those who did not worry.

Personal and workplace characteristics of 169 nurses in Indonesian emergency departments.

| Characteristicsa | No. (range) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 22-57 years | Mean: 35.1 years; SD: 9.06 |

| Work experience | 5-7 years | Mean: 12.6 years; SD: 9.35 |

| Level of worryb | 01-mar | Mean: 3.3; SD: 1.33 |

| 1 | 23 | 13.6 |

| 2 | 18 | 10.7 |

| 3 | 53 | 31.4 |

| 4 | 30 | 17.8 |

| 5 | 40 | 23.7 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 123 | 72.8 |

| Male | 46 | 27.2 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 41 | 24.3 |

| Married | 124 | 73.4 |

| Widow/widower | 4 | 2.4 |

| Employee position | ||

| Nurse manager | 1 | .6 |

| Nurse supervisor | 1 | .6 |

| Head nurse | 9 | 5.3 |

| Assistant head nurse | 5 | 3 |

| Primary nurse | 4 | 2.4 |

| Associate nurse | 148 | 87.6 |

| Type of hospital | ||

| Type A | 76 | 45 |

| Type B | 76 | 45 |

| Type C | 17 | 10.1 |

| Working shift | ||

| Yes | 141 | 83.4 |

| No | 27 | 16.0 |

| Working 18:00-07:00 | ||

| Yes | 102 | 60.4 |

| No | 61 | 36.1 |

| Interact with patients/clients | ||

| Yes | 157 | 92.9 |

| No | 1 | .6 |

| Number of nurses on the same shift | ||

| None | 1 | .6 |

| 1-5 | 75 | 44.4 |

| 6-10 | 52 | 30.8 |

| 11-15 | 34 | 20.1 |

| > 15 | 2 | 1.2 |

| Violence reporting procedure | ||

| Yes | 72 | 42.6 |

| No | 88 | 52.1 |

| Knowledge of how to use violence reporting procedure | ||

| Yes | 53 | 77.9 |

| No | 15 | 22.1 |

| Encouragement to report workplace violence | ||

| Yes | 61 | 36.1 |

| No | 94 | 55.6 |

| Encouragement from (check all that apply) | ||

| Management | 34 | |

| Colleagues | 17 | |

| Family/friends | 9 | |

| Nursing organization | 10 | |

| Information/training about workplace violence | ||

| Yes | 17 | 10.1 |

| No | 150 | 88.8 |

Most nurses reported that they did not have violence reporting procedures in their workplaces. More than half of the participants reported that they received no encouragement to report workplace violence from their workplaces. Very few participants (10.1%) had received any information or training about violence in their workplace.

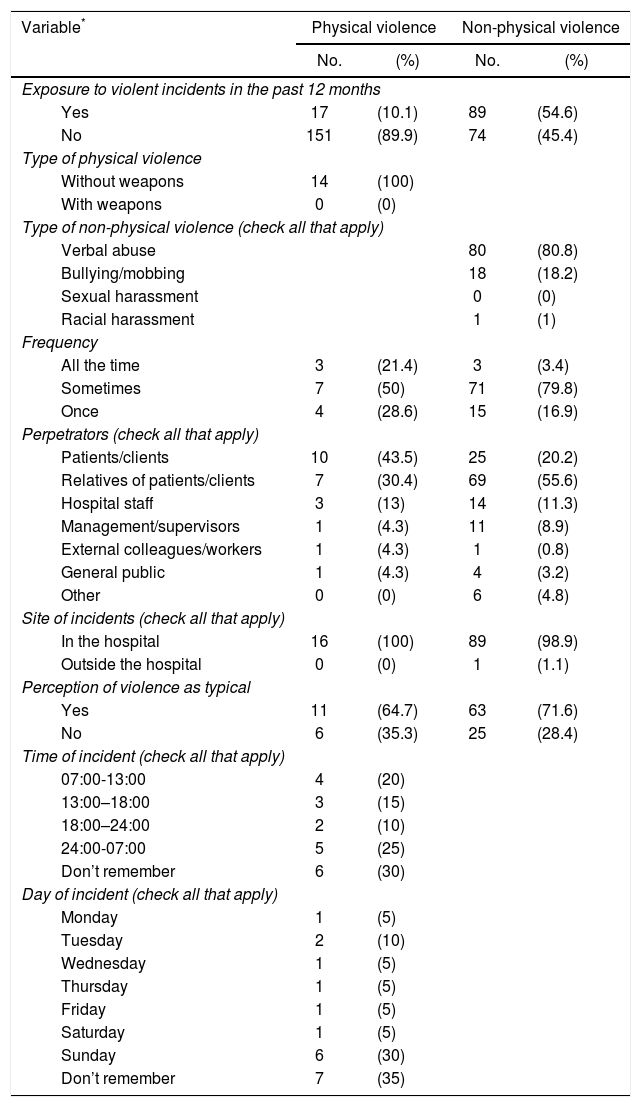

Magnitude and characteristics of workplace violenceTable 2 presents the frequency of violent incidents in the previous 12 months. Seventeen emergency nurses (10%) reported experiencing physical violence, and more than half of emergency nurses (54.6%) reported experiencing non-physical violence. No weapons were involved in any incidents of physical violence. Most incidents occurred between midnight and noon, especially on Sunday. Verbal abuse was the most common type of non-physical violence (80.8%). Patients or clients were the main perpetrators of physical violence (43.5%), while patients’ relatives were responsible for most non-physical violence (55.6%). Almost all incidents of workplace violence against emergency nurses occurred in the hospital.

Frequency of violent incidents.

| Variable* | Physical violence | Non-physical violence | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | (%) | No. | (%) | |

| Exposure to violent incidents in the past 12 months | ||||

| Yes | 17 | (10.1) | 89 | (54.6) |

| No | 151 | (89.9) | 74 | (45.4) |

| Type of physical violence | ||||

| Without weapons | 14 | (100) | ||

| With weapons | 0 | (0) | ||

| Type of non-physical violence (check all that apply) | ||||

| Verbal abuse | 80 | (80.8) | ||

| Bullying/mobbing | 18 | (18.2) | ||

| Sexual harassment | 0 | (0) | ||

| Racial harassment | 1 | (1) | ||

| Frequency | ||||

| All the time | 3 | (21.4) | 3 | (3.4) |

| Sometimes | 7 | (50) | 71 | (79.8) |

| Once | 4 | (28.6) | 15 | (16.9) |

| Perpetrators (check all that apply) | ||||

| Patients/clients | 10 | (43.5) | 25 | (20.2) |

| Relatives of patients/clients | 7 | (30.4) | 69 | (55.6) |

| Hospital staff | 3 | (13) | 14 | (11.3) |

| Management/supervisors | 1 | (4.3) | 11 | (8.9) |

| External colleagues/workers | 1 | (4.3) | 1 | (0.8) |

| General public | 1 | (4.3) | 4 | (3.2) |

| Other | 0 | (0) | 6 | (4.8) |

| Site of incidents (check all that apply) | ||||

| In the hospital | 16 | (100) | 89 | (98.9) |

| Outside the hospital | 0 | (0) | 1 | (1.1) |

| Perception of violence as typical | ||||

| Yes | 11 | (64.7) | 63 | (71.6) |

| No | 6 | (35.3) | 25 | (28.4) |

| Time of incident (check all that apply) | ||||

| 07:00-13:00 | 4 | (20) | ||

| 13:00–18:00 | 3 | (15) | ||

| 18:00–24:00 | 2 | (10) | ||

| 24:00-07:00 | 5 | (25) | ||

| Don’t remember | 6 | (30) | ||

| Day of incident (check all that apply) | ||||

| Monday | 1 | (5) | ||

| Tuesday | 2 | (10) | ||

| Wednesday | 1 | (5) | ||

| Thursday | 1 | (5) | ||

| Friday | 1 | (5) | ||

| Saturday | 1 | (5) | ||

| Sunday | 6 | (30) | ||

| Don’t remember | 7 | (35) | ||

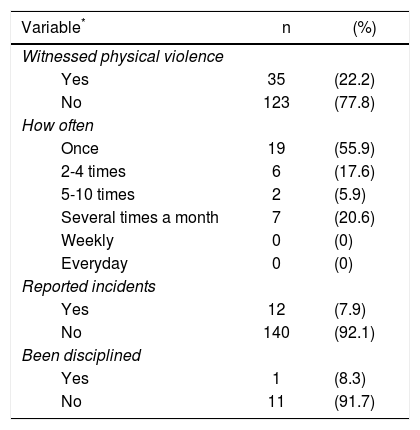

Almost a quarter (n = 35, 22.3%) of the participants reported witnessing incidents of physical violence in the past 12 months, and 22.2% (n=7) had witnessed incidents several times in a month. Most nurses (92.1%) who witnessed violence incidents did not report them (Table 3).

Witnessing incidents of physical violence.

| Variable* | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Witnessed physical violence | ||

| Yes | 35 | (22.2) |

| No | 123 | (77.8) |

| How often | ||

| Once | 19 | (55.9) |

| 2-4 times | 6 | (17.6) |

| 5-10 times | 2 | (5.9) |

| Several times a month | 7 | (20.6) |

| Weekly | 0 | (0) |

| Everyday | 0 | (0) |

| Reported incidents | ||

| Yes | 12 | (7.9) |

| No | 140 | (92.1) |

| Been disciplined | ||

| Yes | 1 | (8.3) |

| No | 11 | (91.7) |

The most common response by victims was to tell their colleagues about violent incidents. Nurses would tell the abusers to stop in cases of physical violence but tolerated more non-physical violence. The majority of the participants regarded workplace violent incidents as preventable.

In the open-ended questions, the participants were asked to identify the three most important factors contributing to violence in the workplace. The most common answers for physical violence were a lack of security guards, ineffective communication and information, and patients’ and relatives’ conditions and cooperation, while the most common responses for non-physical violence were ineffective communication and information, emotional and interpersonal factors, and the setting of emergency departments. In addition, the three most important measures that the participants thought could reduce violence in the workplace were more security guards, improved communication and information, and higher staffing numbers. When asked about the recent news about workplace violence against nurses, within hospitals, most of the participants did not know about the news about workplace violence against nurses. The participants also expressed expectations that violence would not happen in their workplaces and that employees should be provided with clear procedures to prevent and manage violence in the workplace and quickly response to incidents.

DiscussionThe issue of workplace violence against nurses has become a global concern. The majority of data on workplace violence, though, comes from developed countries, such as United States, United Kingdom, and Australia. Information on workplace violence in developing countries is generally lacking. In Indonesia, the research theme of workplace violence against nurses could be perceived as threatening to the nursing profession. Therefore, no research data on workplace violence against nurses were available. This study was the first to explore workplace violence experienced by nurses and the factors associated with violence against nurses in Indonesian emergency departments.

The data obtained from the participants provided profiles of emergency nurses in Indonesia. The majority of emergency nurses were in middle age, with an average age 35.12 years. The number of nurses who worried about violent incidents in their workplaces was higher than those who did not worry. More than half of the participants in this study reported that they did not have violence reporting procedure or encouragement to report workplace violence in their institutions. Moreover, only a few nurses had received any information or training about violence in their workplaces.

The frequency of violent incidents in this study was lower than found in earlier studies on emergency departments in other developing countries, such as Turkey and Iran (Esmaeilpour et al., 2010; Pinar & Ucmak, 2010; Talas et al., 2011). In this study, 10% of emergency nurses experienced physical violence, and 54.6% non-physical violence, much lower than the 41%–75% experiencing physical violence and 80%–91% experiencing non-physical violence in studies from other developing countries (Esmaeilpour et al., 2010; Pinar & Ucmak, 2010; Talas et al., 2011). Although the nurses in this study reported a relative lower rate of workplace violence, the intensity of violence exposure was quite high because most participants reported experiencing either physical or non-physical violence more than once in the past 12 months, as well as witnessing violent incidents in their workplace several times monthly.

The relatively low frequency of violent incidents in this study might indicate that workplace violence against nurses goes largely underreported. It was evident from the data obtained from the participants that the majority (92.1%) did not report incidents of physical violence, either those they witnessed or experienced. Nurses believed that reporting workplace violence would have positive impacts on nurses and their institution or hospital but tended to not report incidents of violence.

The most common reasons for not reporting workplace violence were that the nurses felt that it was not important or useless, did not know who to report to, and feared negative consequences. Some nurses felt that it was not important to report violent incidents because they considered the violent incidents they experienced during their duties as part of the job. In addition, more than half of the participants (52.1%) reported that their institutions did not have violence reporting procedures, so they did not know how or to whom to report violence. A fear of negative consequences for reporting violence was another reason for not reporting violence. A lack of support from management also discouraged nurses from reporting violence. Only around 30% of the victims received support, such as counseling, and were provided opportunities to speak to management. The participants also indicated that they would be more likely to report violence if it happened to others or their colleagues than themselves.

No weapons were used in any incidences of physical violent in this study, and most of the perpetrators were patients. In this study, physical violence commonly happened on Sunday and from midnight until noon, times when more incidents involved traffic accidents and drunken patients. In these cases, the patients’ tended to have confused or disturbed consciousness, which could easily lead to violent incidents. These findings suggested that the physical violence in this study occurred mostly due to patients’ condition, such as confusion of lack of consciousness. This accorded with nurses’ responses to the open-ended questions indicating that the most important contributing factor to physical violence was patients’ condition.

The most common type of non-physical violence in this study was verbal abuse, and the main perpetrators were patients’ relatives. Indonesian emergency departments restrict the number of visitors to patients. Under the regulation, the patients’ family members are not allowed to accompany patients inside emergency department, except for certain reasons, such as cases when the patient needs assistance from family members to explain the procedures or provide consent. Consequently, health care providers, especially nurses, have to care for many patients. In this situation, misunderstandings, ineffective communication, unclear information, and misperceptions often occur. Ineffective communication and unclear information were the most important contributing factors to non-physical violence in the nurses’ responses to the open-ended question. These findings were consistent with Lin and Liu's (2005) study finding that non-physical violence resulted mainly from misunderstandings between patients and visitors, while patients’ confusion was the main reason for physical violence.

Most nurses considered workplace violence to be typical but preventable incidents. Nurses also felt dissatisfied with the manner in which the violence incidents were handled. In addition, polices on violence-related issues and threats were not available in the workplaces of the majority of participants. Consequently, the number of violent incidents against nurses was significantly underreported. The majority of the nurses in this study did not know the recent news about violence against nurses in Indonesia. Nurses’ awareness of their rights and security needs to be emphasized. Clear procedures to prevent and manage violence in the workplace and support for employees are required, as expected by the majority of nurses.

ConclusionsThe frequency of violent incidents against nurses in Indonesian emergency departments was considerable. A lack of support from management and violence reporting procedures were considered to be the reasons why nurses do not report violence. Therefore, management support, written policies, and clear violence reporting procedures are expected to be helpful in managing and preventing violence against nurses in Indonesia.