This study sought to describe the experience of a group of older adults who participated in a chronic illness self-management program.

MethodsThe study employed a qualitative phenomenological approach. Participants were eight elders and data collected using semi-structured interviews Data was analysed using thematic analysis.

ResultsFive themes emerged from the analysis: (1) Tips to improve our daily lives, (2) I was always motivated, (3) Sharing and mutual help, (4) They made us believe we were capable (5). It would be great if it did not end here. Globally, the participants of the program described their experience as very positive. They identified gains from participating in the program, such as learning strategies to help them cope with their health problems, improving their ability to manage their illnesses more autonomously and building social support, that even persisted after the conclusion of the intervention.

ConclusionThe findings of this study provide insight into how older adults experience a program for the self-management of chronic illness. For the development of future programs, support building must be considered. Older adults who participate in self-management programmes exhibit improved self-efficacy in relation to the management their chronic illnesses and greater autonomy in self-care.

Este estudio buscó describir la experiencia de un grupo de adultos mayores que participaron en un programa de autogestión de enfermedades crónicas.

MétodosEl estudio empleó un enfoque fenomenológico cualitativo. Los participantes fueron ocho ancianos y los datos se recogieron mediante entrevistas semiestructuradas. Los datos se analizaron mediante análisis temático.

ResultadosDel análisis surgieron cinco temas: (1) Consejos para mejorar nuestra vida diaria, (2) Siempre estaba motivado, (3) Compartir y ayuda mutua, (4) Nos hicieron creer que éramos capaces (5). Sería estupendo que esto no acabara aquí. Globalmente, los participantes en el programa describieron su experiencia como muy positiva. Identificaron beneficios derivados de la participación en el programa, como el aprendizaje de estrategias que les ayudaran a afrontar sus problemas de salud, la mejora de su capacidad para gestionar sus enfermedades de forma más autónoma y el refuerzo del apoyo social, que incluso persistieron tras la conclusión de la intervención.

ConclusionesLos resultados de este estudio proporcionan una visión de cómo los adultos mayores experimentan un programa para la autogestión de enfermedades crónicas. Para el desarrollo de futuros programas, debe tenerse en cuenta la creación de apoyo. Los adultos mayores que participan en programas de autogestión muestran una mayor autoeficacia en relación con la gestión de sus enfermedades crónicas y una mayor autonomía en el autocuidado.

- -

Structured education in chronic illness self-management, conducted in small groups and facilitated by a healthcare professional, can help participants to improve their health behaviours.

- -

The group intervention reduced participants’ feelings of social isolation, creating groups for sharing which proved to be long-lasting, even beyond the end of the program.

- -

Older adults who participate in self-management programs exhibit improvements in self-efficacy related to their chronic illnesses, as well as greater autonomy in self-care.

More than two-thirds of older adults are living with multiple chronic conditions. As a result, many of them find it challenging to manage and adapt to their multiple illnesses.1 Within this scope, the role of person-centred programs for the self-management of chronic illnesses2–5 is emphasised, particularly the importance of knowing and valuing the individuals’ perspectives, making joint decisions about treatment plans, and encouraging participants’ self-autonomy.6 Individualized and holistic approaches by programs addressing the individual’s history of illnesses, life circumstances, and behaviors are viewed as critical to improving older people’s quality of care.1 Older adults participating in self-management programs show significant improvements in self-efficacy to manage their chronic conditions and enhanced behavioural attitudes, namely the practice of physical exercise and cognitive performance.7

A growing body of evidence suggests that a structured education program in chronic illness self-management, conducted in small groups and facilitated by a healthcare professional (like in the Chronic Disease Self-Management Programme - CDSMP),7 can help participants to improve their health behaviours, manage their illness and treatment regimen, moreover, reduce the use of health services.8 Since older adults usually have more than one chronic illness, the CDSMP applied to this population has produced promising results.7

The CDMSP, developed by Lorig and colleagues at Stanford University Patient Education, is based on some evidence-based assumptions, namely that people with chronic conditions have similar concerns and problems. They are challenged to deal not only with the illness, but with its impact on their lives and emotions; and that the program development process is as important as, if not more important than, the topic being addressed, involving the creation and implementation of action plans.8–10 As such, the CDSMP is a self-management program applicable to any health condition, already successfully implemented among different populations and various settings, with proven effectiveness in improving medication adherence among older adults, including those with depressive-like symptoms; thus, its dissemination has been encouraged.11

In a systematic review study conducted by Mansoor and Khuwaja,7 aiming to evaluate the effectiveness of the program among the elderly population with chronic illnesses, the authors concluded that the older people who participated in the CDSMP improved their self-efficacy in relation to the management of their symptons and illnesses. In addition to improving their self-perceived health, some health behaviours, as for example exercise also increased.

Although the evidence mentioned above has focused on the effectiveness of the self-management programs, it is also important to comprehend the participants’ experience.

In line with this view and within the scope of a broader research project denominated “PT4Ageing: Personal Trainer for the health management of older people”, an intervention program focusing on the self-management of chronic illness was developed. The PT4Ageing global program is a research-action study comprising two components, one more focused on rehabilitation and physical activity and another focused on living well with chronics ilness. These two components had the following goals: a) promote active ageing and the functional capacity of older adults, and b) promote self-management of chronic illness in these individuals.12,14

The present study aims to describe the experience of older adults in the chronic illness self-management component within the PT4Ageing program.

MethodsDesignA qualitative phenomenological study was chosen to describe and understand the experiences of older adults in the chronic illness self-management component within the PT4Ageing program.

Settings and participantsThe program occurred between October 2019 and January 2020, and interviews were conducted six months after the end of the program. The program was publicised to the community by the local Parish Council, following the inclusion criteria: people over 60 years of age; with at least one chronic illness; and freely agreeing to participate in the study. The group was initially composed of ten people who volunteered to participate, aged of 60–86 years, with chronic illnesses and living at home (community-dwelling). Two participants decided to withdraw in the initial phase of the program because of the worsening of their chronic conditions. The remaining eight participants agreed to participate in the program and in the interviews.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Regional Health Administration of the Northern region of Portugal (Opinion No. 1/2018). Participants were informed about the objectives and purpose of the study and signed informed consent.

Program interventionThe development of the PT4Ageing program was partly based on Stanford’s Chronic Disease Self-Management Programme (CDSMP) by Lorig et al.9,10 In the CDSMP, the sessions, in the form of workshops, are implemented by peers with certified training in peer support.9 However, in the intervention described here, the facilitators were healthcare professionals and researchers with training in nursing, psychology, and music therapy. However, following the CDSMP,8–10 the decision was to plan the sessions according to the participants’ needs and interests without following a pre-defined schedule and theme structure.

The component of the PT4Ageing program on the self-management of chronic illness took place in a weekly, face-to-face session, which lasted one hour over three months. Fifteen sessions were held in a space provided by the Parish Council of the participants’ area of residence.

The first session included the presentation of the program, the participants, and facilitators. During session number two, the participants were invited to identify themes related to healthy living and self-management of their chronic illnesses that they found relevant to address during the program. The following sessions were planned sequentially, according to specific objectives and the pace of the group. The content for each session was selected based on information gathered in a diagnostic study, previously conducted with a group from the same population and also based on the particpants reflections on challenges identified in managing their illnesses.12

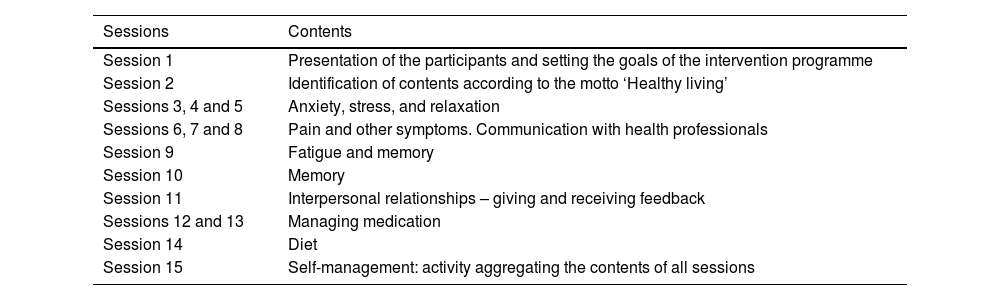

The contents for each session are presented in Table 1: anxiety, stress and relaxation, symptoms management (pain, fatigue, memory changes, and drowsiness), communication with health professionals, medication management, and a healthy diet. Some of the contents were addressed in more than one session, intending to meet the group’s needs and following their appreciation about the revelance of that theme

Contents and sequence of the sessions.

| Sessions | Contents |

|---|---|

| Session 1 | Presentation of the participants and setting the goals of the intervention programme |

| Session 2 | Identification of contents according to the motto ‘Healthy living’ |

| Sessions 3, 4 and 5 | Anxiety, stress, and relaxation |

| Sessions 6, 7 and 8 | Pain and other symptoms. Communication with health professionals |

| Session 9 | Fatigue and memory |

| Session 10 | Memory |

| Session 11 | Interpersonal relationships – giving and receiving feedback |

| Sessions 12 and 13 | Managing medication |

| Session 14 | Diet |

| Session 15 | Self-management: activity aggregating the contents of all sessions |

The facilitators used active methodologies and strategies for group work, as well as gamification. Modelling and rehearsal were used to develop skills like self-massage, physical, and mental relaxation training (with breathing control using imagery techniques).

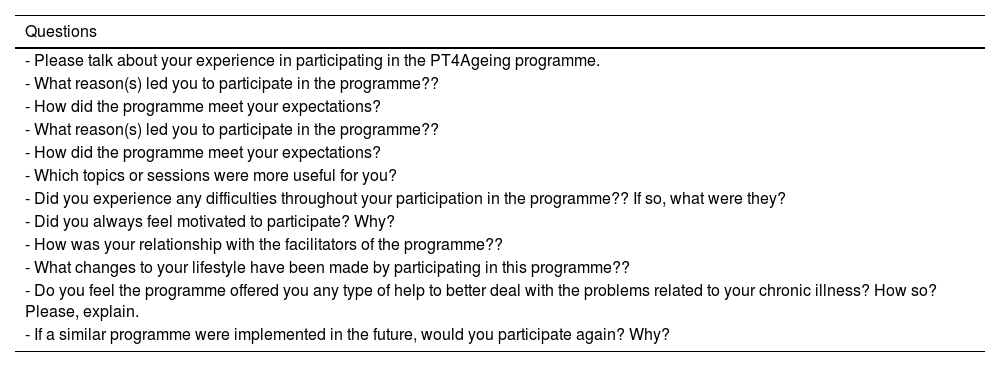

Data collectionSix months after the completion of the program, a researcher who did not participate in the program implementation conducted a semi-structured interview. The Parish Council provided the space for this procedure, and the participants were invited individually. The interview lasted about 45 min and followed the objectives and questions summarized in Table 2.

Interview script.

| Questions |

|---|

| - Please talk about your experience in participating in the PT4Ageing programme. |

| - What reason(s) led you to participate in the programme?? |

| - How did the programme meet your expectations? |

| - What reason(s) led you to participate in the programme?? |

| - How did the programme meet your expectations? |

| - Which topics or sessions were more useful for you? |

| - Did you experience any difficulties throughout your participation in the programme?? If so, what were they? |

| - Did you always feel motivated to participate? Why? |

| - How was your relationship with the facilitators of the programme?? |

| - What changes to your lifestyle have been made by participating in this programme?? |

| - Do you feel the programme offered you any type of help to better deal with the problems related to your chronic illness? How so? Please, explain. |

| - If a similar programme were implemented in the future, would you participate again? Why? |

This script was pre-tested in one exploratory interview with a person with similar characteristics to those of the individuals included in this sample.

Data analysisQualitative data were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim and analysed using thematic analysis.13 Initially, two researchers analysed the interviews individually to highlight meaningful statements and generate the initial codes. Then, the two researchers met to review their findings and discuss differences until a consensus was reached. The third phase consisted of aggregating codes into the themes, and these findings were shared amongst the research team, including the third researcher, who reviewed the analysis. The last phase consisted of settling and naming the final themes.

Results and discussionThe program participants were eight older individuals, of which seven were female, aged between 60 and 86 years, and with four years of schooling. Regarding marital status, they were married or widowed, and almost all lived in a household of two people. Their pension was their primary source of income.

Regarding health status, seven participants had cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, and three had musculoskeletal diseases. The most common pharmacological groups used to control participants’ chronic diseases were cardiovascular drugs (n = 4), analgesics (n = 3), anti-inflammatory medication (n = 3), insulin (n = 3), antidepressants (n = 2), and oral antidiabetics (n = 2). Only two participants were unable to name the medication they were taking.

Five themes emerged from the thematic analysis of the interviews: ‘Tips to improve our daily lives’; ‘Sharing and mutual help’; ‘I was always motivated’; ‘They made us believe we were capable’, and ‘It would be great if it did not end here’.

Tips to improve our daily livesThe elders viewed the experience of participating in PT4Ageing program as a benefit for the self-management of their health and chronic illness. Moreover, the program contemplated the main difficulties associated with the self-management of chronic illnesses, particularly those most common in older individuals, such as cardiovascular diseases, musculoskeletal diseases, and diabetes, among others.15 The participants made many references to the program content, expressing an overall perception of its content diversity that also met their actual needs. They highlighted topics related to the management of physical health (food, physical exercise, medication) and psychosocial health (management of mental health, stress, and anxiety). Participants had different perceptions of the program’s content, probably related to the areas that better responded to their health needs. For example, one of the participants highlighted the ‘relaxation exercises’ (P.7) she performed and continues to perform to deal with anxiety in her daily life. Interpersonnal skills were also mentioned,as for example, ‘before the programme, I wouldn't even talk to people…’ (P.4).

They also recognized that the program enhanced their health literacy by addressing issues relevant to daily management of their symptons, for promoting physical16 and mental health and learning how to maintain a healthy life and well-being, despite their chronic illnesses. Similar experiences were described in a study with 51 youths with spina bifida who participated in a self-management program. Adolescents were asked to participate in a focus-group after completing the programme, during which they reported, for example, the acquisition of skills for problem-solving in areas related to their autonomy.17

The participants also mentioned the program’s benefits for facing challenges that later emerged associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, stating, ‘Then, the pademic… but we still called and text each other …” (P7) and ‘But it was fantastic, it was important to prepare us, none of us could ever imagine what was coming, it gave us more strength.’ (P3)

I was always motivatedThe participants referred to different reasons for taking part in the program, but they all recognized the effort of the facilitators to motivate engagement in each session and throughout the whole programme. Participants expressed that they were highly motivated throughout the sessions due to the variety of themes and group dynamics. They stressed the importance of the many strategies used, including those that used as resources music, videos, presentations, games, arts and crafts.

They also noted that the motivation for participating in the program was initially related related to feelings of sadness and the experience of loneliness. They expected that the the participation in the program could provide an opportunity to interact with other people and learn something significant for their health. This motivation extended to the entire group, reflected in a statement by one of the participants, ‘The program took place over the winter, during a time of rain and wind, and nothing held us back. We would come here anyway, there were very few absences.’ (P3). One of the participants added, ‘At the beginning, it was just out of curiosity, but then I liked it and loved it’ (P3).

Sharing and mutual helpThe reported experiences reveal that participants strongly valued the development of interpersonal relationships, especially the mutual help fostered among participants by the facilitators of the program, referred to by one participant as ‘a program of affection’ (P3). Participants mentioned moments of interaction and sharing of ideas, as well as the well-being and satisfaction associated with the feeling of belonging to the group. This feeling of belonging was reported as something that reduced the social isolation. The development of social support is one of the key ingredients of group interventions as is case of the CDSMP approach, that has already proved its efficacy in improving psychosocial health.

There were reports of mutual encouragement and support among participants, ‘At the time, I had a colleague who brought us small papers so that we could write down our medication, to take our medication on time, …, and I still have that written down…’ (P4).

Moreover, the strengthening of trust within the group was highlighted. The sharing of goals, the enhancement of skills to manage their health, the proximity between participants and their openness to the group increased throughout the sessions. One of the participants mentioned that ‘…we were slowly able to remove our – masks -, each of us was able to take off our – mask -, we were able to give more of ourselves, start to expose ourselves.’ (P3).

Similarly, the relationship between the participants and the facilitators of the PT4Ageing program was described as very good, with the participants adding that the facilitators were able to foster a sense of belonging and give meaning to the group. As stated by one participant, ‘Because they said the group was very good, but I think the people created it, and the group appeared… and we were part of this group.’ (P3).

Some participants mentioned that the program reduced feelings of loneliness, not only during its implementation but also after its conclusion. The communication between group members using WhatsApp and telephone was maintained and provided a privileged space for encouragement and support. The promotion of social support and consequently the reduction of loneliness has been already shown in in community-dwelling older people who participated in a nurse-led community intervention.18,19

They made us believe we were capableParticipants reported that the program gave them knowledge and skills to promote their health, despite their advanced age and chronic illnesses, and that it improved their self-efficacy and autonomy for self-care, mentioning that ‘They made us believe we could do it’ (P3) and ‘It increased our responsibility’ (P3). For example, a participant with fibromyalgia reported better chronic pain management, stating that ‘I think… I can’t stop… it’s worse for the pain. And I think ‘get up, come on get up, come on you must walk’. And the words I learned here were encouraging. Because it’s worse if I stop.’ (P1)

Greater autonomy in daily activities was also report, with participants mentioning having learned strategies for improvement at this level. For example, one participant pointed out, I feel better than I felt before, because I’ve improved. I feel more capable than before. It encouraged me and now there are things I can do by myself…. (P4).

These findings are in line with the results of several other studies. In the the systematic literature review conducted by Mansoor and Khuwaja,7 the results showed that older people who attended program for the self-management of their chronic illnesses reported an improvement in their self-efficacy to deal with illness-related symptoms and distress and also increased their health behaviours. Evidence also indicates that the improvement of self-efficacy has a positive impact on the management of treatment regimens and provides better meaning to the lives of individuals.3 Understanding this topics will support health professionals to identify approaches to self-management that meet the needs of individual older adults.20

On the other hand, the development of ‘responsible self-care’ means the older person develops his or her daily activities in a responsible manner, facing life and ageing in a positive way, preserving the desire to live, and maintaining social ties.21,22 These study findings seem to indicate that participants improved their responsibility in self-care, and they had a greater desire to live and preserve the support created during the program, which lingered until the interviews.

It would be great if it did not end hereThe analysis of the interviews revealed that participants’ perceived the program as very positive, through statements such as ‘Very useful, very positive’ (P1; P4; P5; P6; P7); ‘Very good’ (P1; P2; P4; P5; P6) and ‘I loved it. We all did’ (P7). Some participants stated it was ‘a joy’ (P4) to participate in the program. As for the duration of the program, the participants considered that it ‘Needed more time’ (P1), and ‘…to be repeated’ (P5), with some participants suggesting that future planning should include an extension from two to three days per week, or two-hour sessions. Moreover, participants expressed their willingness to participate in future program and that they would recommend it to others.

One of the participants evaluated the program, as ‘People have no idea how beneficial it is to participate in these programs. These meetings, these people, how helpful it is. Feeling like I’m still alive, like I’m still a person … to enjoy everything I can, that’s the goal… that small amount of time, I don’t know… it was a simple gesture that helped us, our lives to become meaningful, a stronger will to live…’ (P6).

The participants’ reports evidencing the positive effects on well-being and chronic illness management suggest that the PT4Ageing program is a valuable tool to foster well-being and self-efficacy, in line with other studies findings.2,5

One important limitation of this study was the small sampling number. However, the eight elderly who started the program were actively involved throughout all 15 sessions. The participants showed several gains related to self-management, so it would be interesting to further investigation evaluated the experience by addressing the changes implemented in their daily lives, an aspect that was not explored in this present study.

ConclusionThe findings show that participants considered the program very positive, considering the content and strategies used in promoting the self-management of chronic illnesses. The group intervention helped to reduce participants’ feelings of social isolation and created excellent opportunities for support, which extended beyond the end of the program. The participants’ testemonies revealed an improvement in the participants’ self-efficacy and autonomy in self-care.

The results of this study are in line with evidence that show the usefulness of this type of program in the self-management of chronic disease, adding the experience of its participants. Furthermore, knowing the views of those involved in the program highlighted the benefits of the support provided through the group intervention that included personalised and targeted responses to the real needs of the older people.

Conflict of interest statementThe authors are solely responsible for the content and writing of the paper. The authors report no conflicts of interest. National Funds through FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, I.P., within CINTESIS, R&D Unit (reference UIDB/4255/2020 and reference UIDP/4255/2020), supported this article.

Funding statementThe author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ContributionsStudy conception and design, and drafting of the manuscript: CSF, LL, SC, MC, CS, and CB; data analysis: CS and LL; critical revisions for intellectual content: CSF, LL, SC, MC, CS, and CB.

Ethical approvalThe study was carried out in accordance with the principles in the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Regional Health Administration of the Northern region of Portugal in January 2018 (Opinion no. 1/2018). Both written and oral information were provided stating that participation was voluntary, confidentiality was assured, and that participants could withdraw from the study at any time with no negative consequences. Informed consent was obtained from each participant.

We are very grateful to the PT4 ageing program participants.