Care in the Intensive Care Unit involves contemplating, among other dimensions of the patient, the family. For this, it is necessary for the nurse to establish relationships with the patient's relatives.

ObjectiveTo identify the way in which the nurse-family relationship is established in the adult ICU, as well as the conditions, elements and factors that favour or hinder it.

MethodIntegrative narrative review of the scientific literature. The databases consulted were Ovid, PubMed, Science Direct, Scopus, Clinical Key, Google Scholar and Scielo. Articles in English and Spanish published between 2014 and 2018 were searched. The descriptors and formulas used were selected according to the acronym Population and their problems, Exposure and Outcomes or themes- PEO. The population comprised ICU nurses and the relatives of patients in critical condition; Adult Intensive Care Unit exposure or context; the expected results, and how they are related. For the methodological evaluation, the STROBE guide was used for observational articles, PRISMA for review articles, COREQ for qualitative articles and CASPe for articles derived from projects.

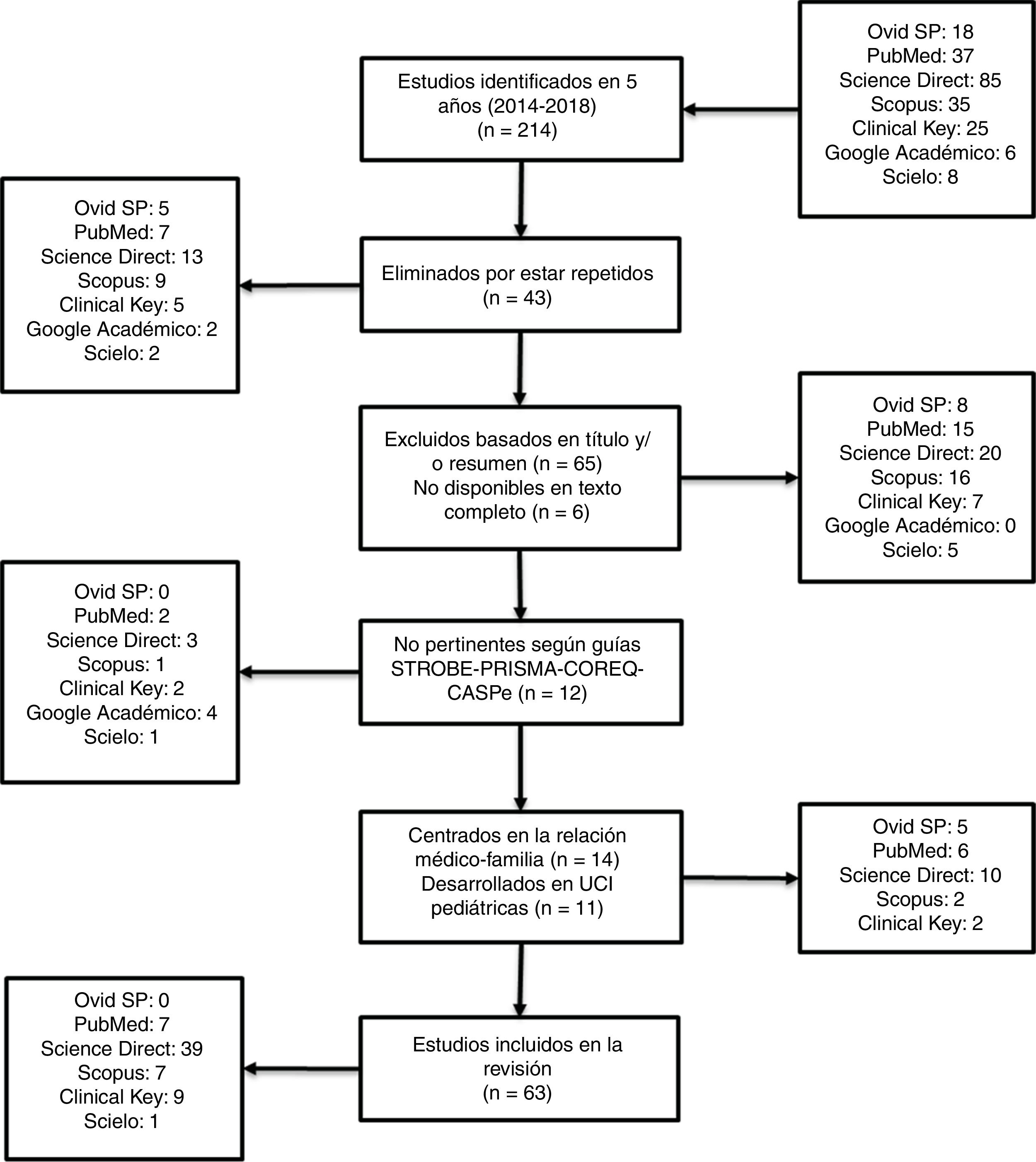

ResultsWe identified 214 articles, of which 63 were selected to be included in the review. The central themes identified were: the ICU environment and its effects on the family, empathy as an indicator of relationship, interaction as a means of relating, communication as the centre of relationships and barriers to the establishment of relationships.

ConclusionsThe nurse-family relationship in the Intensive Care Unit is based on interaction and communication amidst human, physical, regulatory and administrative barriers. Improving the nurse-family relationship contributes to the humanization of Adult Intensive Care Units.

El cuidado en la Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos implica contemplar, entre otras dimensiones del paciente, a la familia. Para esto es necesario que la enfermera establezca relaciones con los familiares del paciente.

ObjetivoIdentificar la forma como se establece la relación enfermera- familia en la UCI adultos, al igual que las condiciones, elementos y factores que la favorecen o la dificultan.

MétodoRevisión narrativa integrativa de la literatura científica. Las bases de datos consultadas fueron: Ovid, PubMed, Science Direct, Scopus, Clinical Key, Google Académico y Scielo. Se buscaron artículos en inglés y español publicados entre el 2014 y el 2018. Los descriptores y fórmulas utilizadas se seleccionaron de acuerdo al acrónimo Population and their problems, Exposure y Outcomes or themes- PEO. La población correspondió a las enfermeras de UCI y los familiares de pacientes en estado crítico; la exposición o contexto a la Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos adultos; y los resultados esperados, a la forma como estos se relacionan. Para la evaluación metodológica se utilizaron la guía STROBE para artículos observacionales, PRISMA para artículos de revisión, COREQ para artículos cualitativos y CASPe para artículos derivados de proyectos.

ResultadosSe identificaron 214 artículos, de los cuales se seleccionaron 63 para ser incluidos en la revisión. Las temáticas centrales identificadas fueron: el entorno de la UCI y sus efectos sobre el familiar, la empatía como indicador de la relación, la interacción como medio para relacionarse, la comunicación como centro de las relaciones y las barreras para el establecimiento de relaciones.

ConclusionesLa relación enfermera- familia en la Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos se da a partir de la interacción y la comunicación en medio de barreras humanas, físicas, normativas y administrativas. Mejorar la relación enfermera- familia contribuye a la humanización de las Unidades de Cuidados Intensivos adultos.

The humanisation of health services and, in particular, of intensive care units (ICUs), has resulted in the incorporation the "patient and family-centred care" concept, which aims to create an approach to care in which the family takes on greater relevance and importance within the health services.1,2 The principles of this concept are information sharing, respect for differences, and collaboration, negotiation and care in the family and community context.1

This enables progression from patient-centred care to a holistic model that recognises the needs of the family as inseparable from those of the patient.3 However, the complexity of ICU dynamics can mean that the human needs of the patient and his/her family become a secondary concern. Arias-Rivera and Sánchez-Sánchez5 explain that there is still a need in ICU to improve on aspects such as empathy with the feelings and concerns of family members, the comfort of units and coordination of staff with relatives.

Lor et al.6 noted that family-centred care in the ICU promotes better communication and understanding of the patient, and reduces anxiety, post-traumatic stress, and depression in family members. It also provides an opportunity to teach and involve family members in the care of the patient, which improves the safety of the service as well as patient and family satisfaction.7–10

The project "Humanising Intensive Care"11 (HU-CI) was created in Spain in 2014, to provide a rallying point for patients, families and professionals to disseminate and bring intensive care closer to the general population and to promote training in humanisation skills. Its 8 strategic lines involving a close relationship with the family include "open door ICU", "communication", "presence and participation of family members in intensive care" and "prevention, management and monitoring of post-intensive care syndrome".1,4

The involvement of family members in the ICU can have positive effects for them as well as the patient, as it helps to reduce emotional stress and facilitates closeness and communication with the patient and professionals.11 In this sense, Fawcett12 considers communication to be the vehicle by which human relationships are developed and maintained and as a process by which information is transmitted from one person to another, in a face-to-face encounter.11,13

Furthermore, opening doors in the ICU favours the integration of relatives, in that this strategy aims to eliminate all unnecessary limitations of a temporary, physical and relational nature, by enabling them to become actively involved,14 and interact more frequently with care staff.4 Thus, it highlights the importance of interaction in the process of involving family members in the dynamics of the ICU. In this respect, Meleis15 recognises that relationships are formed through interaction.

Post-intensive care syndrome-family refers to the mental, cognitive and physical conditions experienced by relatives of critically ill patients, which result from intense and alternating feelings and which favour the development of long-term psychological effects, such as anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress.16–20 This is reflected in crises within the family that can lead them to neglect their own health. Therefore, prevention of this syndrome in family members will help them to re-enter social activities, re-establish family dynamics and prevent mental health disorders.

The anxiety, depression, uncertainty and stress frequently experienced by relatives in the ICU leads them to consider that nurses are in the best position to relate to them.19–24 However, these relationships occur in a context where both the environment and resources available for care of the family are potential barriers to relatives becoming involved in the care of the patient.24–27

Koukouli et al.16 argue that an inclusive framework for the family in acute care should be promoted and implemented through the development of strategies to improve communication between nurses and relatives of critically ill patients. In this regard, Padilla-Fortunati et al.28 and Velasco-Bueno et al.29 believe that such a framework can contribute towards empathetic and supportive relationships.

In line with the above, establishing relationships emerges as a central element in the humanisation of care in the ICU, as these relationships help towards an understanding of the meaning of the experience, in this case, of the family member.30 Carper31 recognises relationships as an element that helps to develop skills to understand the meanings that arise from nurse-client encounters.

Although aspects that contribute to the establishment of relationships such as interaction and communication are identified, the way in which the relationship is built between relatives and nurses is unknown. Based on the above, the aim of this study was to identify how the nurse-family relationship is established in the adult ICU, as well as the conditions, elements and factors that favour or hinder it.

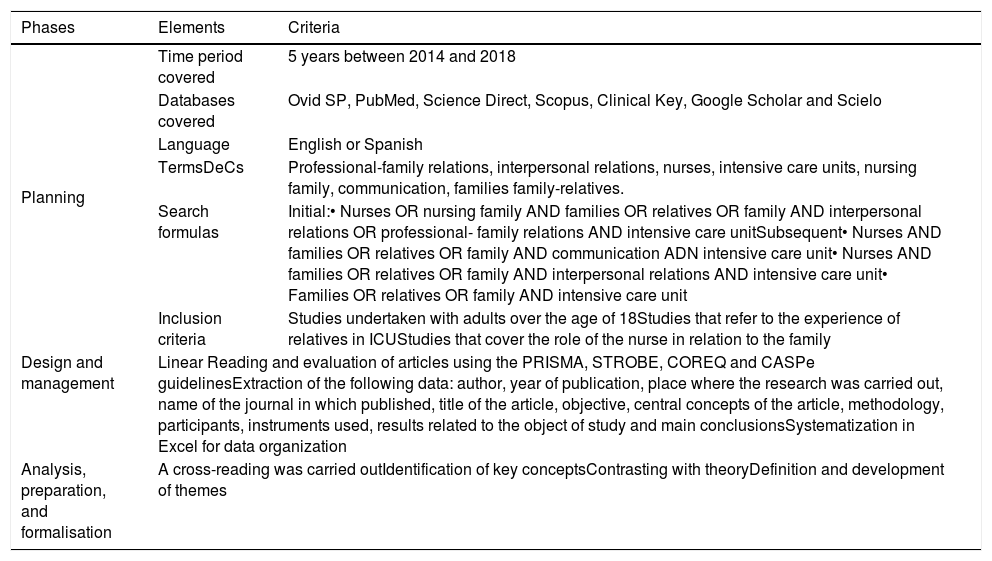

MethodThe present study is an integrative narrative review32 of the scientific literature on the nurse-family relationship in ICU. The study was conducted in 3 stages: planning; design and management; and analysis, elaboration and formalisation.33,34 These stages were framed within the proposals of the PRISMA statement to improve the publication of systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

In the first stage, search strategies were established to enable a systematic review of the scientific literature. The descriptors and formulas used to search for information were selected according to “Population and their problems, Exposure and Outcomes or themes (PEO)”.35 The population corresponded to ICU nurses and relatives of critically ill patients; exposure or context, corresponded to the adult intensive care unit and expected outcomes, and to how these are related. The DeCs descriptors and formulas used are described in Table 1, in addition to the criteria of inclusion, exclusion and search filters.

Methodological process for the search, systematization, and analysis of scientific articles.

| Phases | Elements | Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Planning | Time period covered | 5 years between 2014 and 2018 |

| Databases covered | Ovid SP, PubMed, Science Direct, Scopus, Clinical Key, Google Scholar and Scielo | |

| Language | English or Spanish | |

| TermsDeCs | Professional-family relations, interpersonal relations, nurses, intensive care units, nursing family, communication, families family-relatives. | |

| Search formulas | Initial:• Nurses OR nursing family AND families OR relatives OR family AND interpersonal relations OR professional- family relations AND intensive care unitSubsequent• Nurses AND families OR relatives OR family AND communication ADN intensive care unit• Nurses AND families OR relatives OR family AND interpersonal relations AND intensive care unit• Families OR relatives OR family AND intensive care unit | |

| Inclusion criteria | Studies undertaken with adults over the age of 18Studies that refer to the experience of relatives in ICUStudies that cover the role of the nurse in relation to the family | |

| Design and management | Linear Reading and evaluation of articles using the PRISMA, STROBE, COREQ and CASPe guidelinesExtraction of the following data: author, year of publication, place where the research was carried out, name of the journal in which published, title of the article, objective, central concepts of the article, methodology, participants, instruments used, results related to the object of study and main conclusionsSystematization in Excel for data organization | |

| Analysis, preparation, and formalisation | A cross-reading was carried outIdentification of key conceptsContrasting with theoryDefinition and development of themes | |

In the second stage, a linear critical reading of the articles was carried out to assess their quality and methodological structure. For this assessment, we used the STROBE guide for observational articles, PRISMA for review articles, COREQ for qualitative articles, and CASPe for project derived articles. This helped to standardize and systematize the reading and review of the articles, as well as to determine their methodological rigor and scientific validity when defining their relevance according to the subject matter and purpose of the study.

The articles included in the study were systematized in an Excel matrix in which the following were specified: author, year of publication, place where the research was carried out, name of the journal where it was published, title of the article, objective, central concepts of the article, methodology, participants, instruments used, results related to the object of study and main conclusions. The central concepts of the article were identified in 2 ways. The first, recognising the central phenomenon of study in the objective and the way it was conceptually represented by the authors; and the second, recognising the main concept or concepts addressed in the results.

In the third phase, the analysis and interpretation of the concepts, results and conclusions were addressed, allowing the identification of themes and sub-themes.

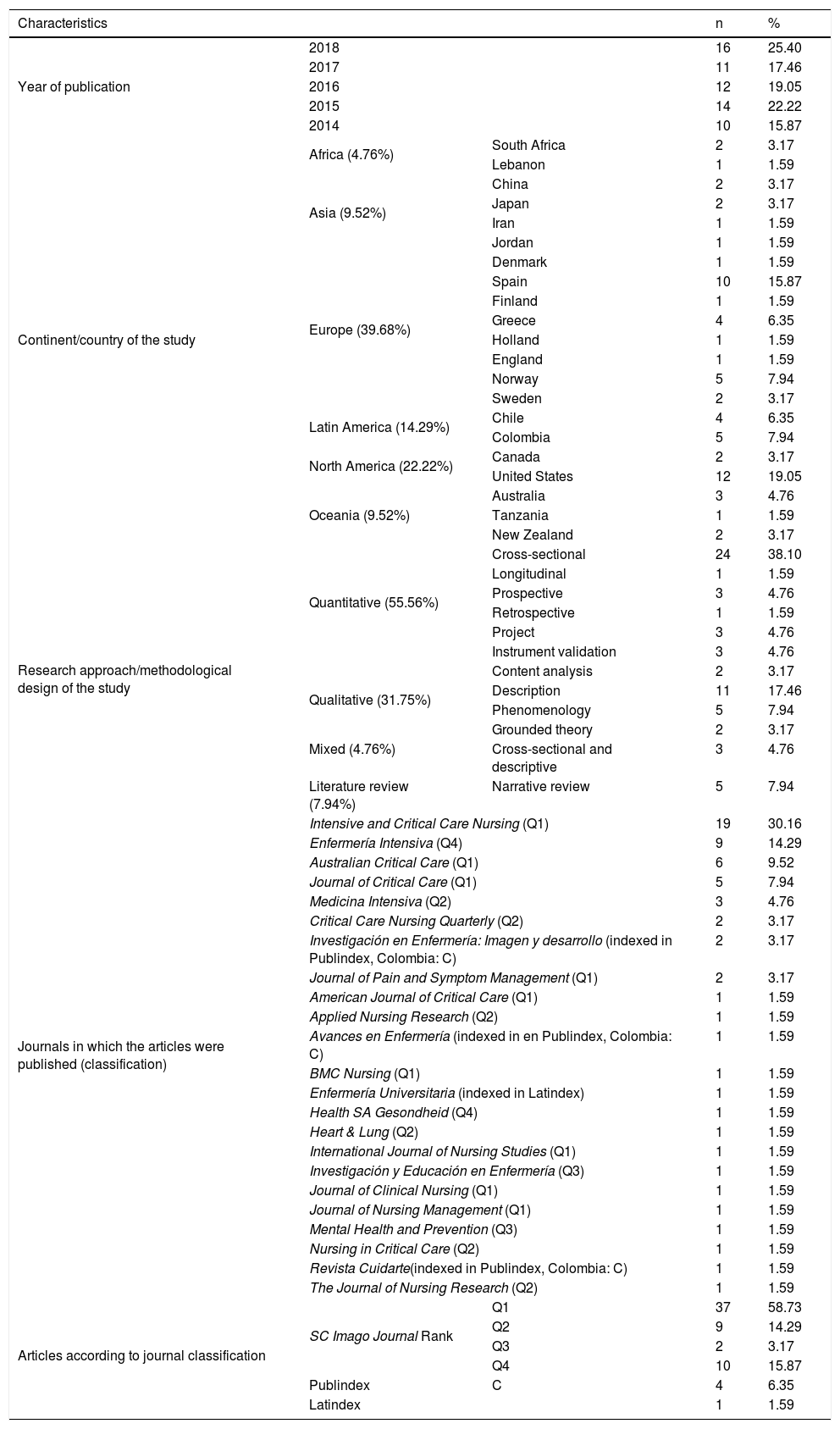

ResultsSixty-three articles were selected for the narrative review, after following the process described in Fig. 1.

The articles came from 23 journals, of which Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, Enfermería Intensiva, Australian Critical Care and Journal of Critical Care had the largest number of publications on the theme. Of the journals consulted, 19 were classified in the SCImago Journal Rank (SJR); the rest were classified in Publindex and Latindex. Of the articles included in the narrative review, most were published in Q1 journals. In relation to the geographical area where the studies were carried out, most were in the European continent and, within it, Spain. The methodological approach of the studies was mainly quantitative. Fewer mixed studies were found, corresponding to those in which both quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis techniques were used. The characteristics of the publications included in the review are detailed in Table 2.

Characteristics of the articles included in the narrative review.

| Characteristics | n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of publication | 2018 | 16 | 25.40 | |

| 2017 | 11 | 17.46 | ||

| 2016 | 12 | 19.05 | ||

| 2015 | 14 | 22.22 | ||

| 2014 | 10 | 15.87 | ||

| Continent/country of the study | Africa (4.76%) | South Africa | 2 | 3.17 |

| Lebanon | 1 | 1.59 | ||

| Asia (9.52%) | China | 2 | 3.17 | |

| Japan | 2 | 3.17 | ||

| Iran | 1 | 1.59 | ||

| Jordan | 1 | 1.59 | ||

| Europe (39.68%) | Denmark | 1 | 1.59 | |

| Spain | 10 | 15.87 | ||

| Finland | 1 | 1.59 | ||

| Greece | 4 | 6.35 | ||

| Holland | 1 | 1.59 | ||

| England | 1 | 1.59 | ||

| Norway | 5 | 7.94 | ||

| Sweden | 2 | 3.17 | ||

| Latin America (14.29%) | Chile | 4 | 6.35 | |

| Colombia | 5 | 7.94 | ||

| North America (22.22%) | Canada | 2 | 3.17 | |

| United States | 12 | 19.05 | ||

| Oceania (9.52%) | Australia | 3 | 4.76 | |

| Tanzania | 1 | 1.59 | ||

| New Zealand | 2 | 3.17 | ||

| Research approach/methodological design of the study | Quantitative (55.56%) | Cross-sectional | 24 | 38.10 |

| Longitudinal | 1 | 1.59 | ||

| Prospective | 3 | 4.76 | ||

| Retrospective | 1 | 1.59 | ||

| Project | 3 | 4.76 | ||

| Instrument validation | 3 | 4.76 | ||

| Qualitative (31.75%) | Content analysis | 2 | 3.17 | |

| Description | 11 | 17.46 | ||

| Phenomenology | 5 | 7.94 | ||

| Grounded theory | 2 | 3.17 | ||

| Mixed (4.76%) | Cross-sectional and descriptive | 3 | 4.76 | |

| Literature review (7.94%) | Narrative review | 5 | 7.94 | |

| Journals in which the articles were published (classification) | Intensive and Critical Care Nursing (Q1) | 19 | 30.16 | |

| Enfermería Intensiva (Q4) | 9 | 14.29 | ||

| Australian Critical Care (Q1) | 6 | 9.52 | ||

| Journal of Critical Care (Q1) | 5 | 7.94 | ||

| Medicina Intensiva (Q2) | 3 | 4.76 | ||

| Critical Care Nursing Quarterly (Q2) | 2 | 3.17 | ||

| Investigación en Enfermería: Imagen y desarrollo (indexed in Publindex, Colombia: C) | 2 | 3.17 | ||

| Journal of Pain and Symptom Management (Q1) | 2 | 3.17 | ||

| American Journal of Critical Care (Q1) | 1 | 1.59 | ||

| Applied Nursing Research (Q2) | 1 | 1.59 | ||

| Avances en Enfermería (indexed in en Publindex, Colombia: C) | 1 | 1.59 | ||

| BMC Nursing (Q1) | 1 | 1.59 | ||

| Enfermería Universitaria (indexed in Latindex) | 1 | 1.59 | ||

| Health SA Gesondheid (Q4) | 1 | 1.59 | ||

| Heart & Lung (Q2) | 1 | 1.59 | ||

| International Journal of Nursing Studies (Q1) | 1 | 1.59 | ||

| Investigación y Educación en Enfermería (Q3) | 1 | 1.59 | ||

| Journal of Clinical Nursing (Q1) | 1 | 1.59 | ||

| Journal of Nursing Management (Q1) | 1 | 1.59 | ||

| Mental Health and Prevention (Q3) | 1 | 1.59 | ||

| Nursing in Critical Care (Q2) | 1 | 1.59 | ||

| Revista Cuidarte(indexed in Publindex, Colombia: C) | 1 | 1.59 | ||

| The Journal of Nursing Research (Q2) | 1 | 1.59 | ||

| Articles according to journal classification | SC Imago Journal Rank | Q1 | 37 | 58.73 |

| Q2 | 9 | 14.29 | ||

| Q3 | 2 | 3.17 | ||

| Q4 | 10 | 15.87 | ||

| Publindex | C | 4 | 6.35 | |

| Latindex | 1 | 1.59 | ||

Two strategies were used to identify the central themes of the study. On the one hand, a theoretical and conceptual review of the concept of relationship that allowed it to be identified as based on interaction and communication, aspects that were also evident in the cross-reading of the articles. On the other hand, additional concepts emerged from this reading, such as the needs and emotions of family members in the ICU and barriers to relations. Thus, 5 themes were identified, on which the narrative was developed: the ICU environment and its effects on the family member, empathy as an indicator of relationship, interaction as a means of relating, communication as the centre of relationships and barriers to establishing relationships. Appendix B annex of the supplementary material corresponding to Table 3, gives a summary of the articles included in the review.

DiscussionThe intensive care environment and its effects on family membersThe exposure of relatives to the ICU context, where everything happens quickly36,37 and an environment that is unfamiliar and frightening, can make them feel overwhelmed,18 distressed, anxious38–41 and worried, leading them to a state of uncertainty,25,42,43 which can be increased by a lack of predictability and information.43 This situation can also cause family members to feel frustrated, remorseful, lose trust and experience feelings of guilt about the condition of their relative.16,25,36,39,44

In addition, families have an intense need for information.28,38,45–50 Murillo-Pérez et al.51 suggest that is the most significant need for relatives because information provides understanding and a greater sense of control which helps reduce negative emotions. For this reason, communication is a fundamental element, as through it relatives can learn about the disease, the therapeutic plan, possible sequelae and the patient's prognosis.38,45,46,49,50 Relatives expect the information provided to them to be honest, to answer their questions appropriately and to be explained in understandable terms.52,53

Family members in the ICU also have a need for proximity.3,38,48 This is reflected by the desire to be close to their loved one at the critical moment, which gives them a sense of more control and impact on what their relative is undergoing. In addition to the above, it allows the relative to be viewed as someone important to the patient and to receive more support from staff.3,38,53,54

Mitchell and Aitken38 consider that the presence of the nurse brings the family closer to patients. Aliberch-Rurell and Miquel-Aymar,3 Kohi et al.55 and Rojas-Silva et al.56 explain that allowing the family to participate in the care of their sick relative favours an integrated vision of care and the nurse-client/family relationship, since it allows them a better knowledge of the patient, their environment, values, culture and other aspects.

Empathy as an indicator of relationshipMontoya-Tamayo et al.57 recognise that nurses need to take a more active role in the relationship they establish with the family. These authors identify "empathy" as the necessary element for such relationships to take place and for nurses to be able to commit to accompanying the family.58 Parrado-Lozano et al.59 define empathy as the capacity of the nurse to experience the subjective reality of the patient or family in such a way that they can respond adequately to their needs and help them express their feelings.

Establishing relationships helps nurses to increase the trust of family members, which means they can be recognised as an emotional support for patients and as part of the treatment.60 Similarly, relationship building helps nurses to support family members during the hospitalisation process by helping them to have hope, trust, make decisions and prepare to accept an impending death.61–63

Some of the approaches that some nurses have adopted to gain the trust of family members and encourage relationship building include sharing their own experiences,24 recognising the diverse cultures of family members while respecting their knowledge and opinions,64 showing interest in the family by asking about personal stories in conversations with relatives, offering drinks, food and a place to sleep,65 being attentive, empathetic and understanding, holding the hand of the grieving relative and providing friendly, reassuring and active listening.58 This can help family members cope with the stress of an ICU admission64 and facilitate healthy and effective family involvement.24

Interaction as a means of relatingBernal-Ruiz and Horta-Buitrago52 emphasize that family-nurse interaction is key to providing comprehensive care, avoiding adverse psychological effects, and generating humanized therapeutic environments free from negative connotations.

Some of the elements that favour the interaction of the nurse with family members are those referred to by Parrado-Lozano et al.59 as guidance and participatory care. The first refers to the ability to guide the family on the rules and functioning of the ICU. The second refers to the ability to involve the family member in a voluntary, gradual and guided way in the care of their patient.66 Asencio-Gutiérrez and Reguera-Burgos67 explain that allowing the presence of the family member would avoid the feeling of abandonment that occurs while the sick relative is being cared for inside the ICU.

To improve interaction between the nurse and the family, Kozub et al.68 propose that extending ICU visiting hours is a key strategy to increase the involvement of the family in patient care.69 On the other hand, Noome et al.65 identified that scheduling meetings with the family are spaces where interaction between nurse and family is achieved, which can improve family satisfaction as they can ask any questions and express their emotions.

Another element that favours interaction is when the nurse encourages family members, reassures them with words of encouragement and shows interest when they express their concerns or distress. Similarly, responding to any concerns, demonstrating patience in explaining procedures, talking to them in a friendly and calm manner and greeting relatives when they arrive at the ICU also contribute to a favourable perception of nurses by relatives.58

Communication at the heart of relationshipsCommunication between the nurse and the family in ICU is highly valued and considered a central construct in the interpersonal relationship between the nurse and the family59,65 as the experiences and interactions between the two are centred around communication47 and, ultimately, it is the nurse who constructs the story for the family.70

Wong et al.47 propose that for some families it is easier to communicate with the nurse because they are friendlier and more accessible, and the information is clearer, which makes what they are saying, what is happening and what to expect easier to understand.42,58,71 Thus, nurses become a channel of communication between the professionals of the unit and the family47 simplifying and contextualising complex medical information.46,72 Therefore, the need is recognised for nurses to have informed conversations with families after a doctor has left the unit.47,72

Schubart et al.73 argue that effective communication in the ICU setting depends on the ability of participants to construct messages that are aligned with the needs of the moment. To this end, the nurse uses communication strategies, which are defined as the ability to include different ways of conveying and receiving messages in a particular context of interaction with the family member.59

On the other hand, previously planned meetings favour the family's understanding of the situation, in addition to being a space in which explanations can be given of the patient's condition and progress and the functioning of the ICU.46,74 Akroute and Bondas60 identified that in some cases communication between the nurse and the family improves when the latter have gained information beforehand through media such as the Internet.

Au et al.75 state that the information that can be addressed in meetings or rounds with families is the discussion of diagnoses and care plans; however, they recommend that the objectives of care, the patient’s status and prognosis and emotional support be discussed in private family meetings.59,76

Barriers to establishing relationshipsOne of the barriers identified to the relationship between the nurse and the family is the predisposition of the nurse towards families. Montoya-Tamayo et al.57 identified that some nurses focus their care on the patient and do not consider their relatives and show less interest in family concerns.29 Thus, the nurse's prioritisation of care, treatment and the biological condition of the patient may result in the family not being considered in their care plan.3,43 In this regard, Beer and Brysiewicz64 propose that adopting a purely medical model in patient care causes the presence of the family to be undervalued.

However, there are also situations where families perceive that nurses do not understand their reactions, which can be difficult but are human.25,53 Thus, some families consider that ICU nurses do not show empathy,42,58 since they speak in an aggressive manner,25,77,78 are not concerned if the family member is upset and care even less about their state of mind, and do not approach them to reassure them if they see them in distress, they do not talk to the relatives, they do not ask about the problems they are facing with the situation of their sick relative, they do not answer politely, they frown when asked repeated questions, they appear annoyed,58 cold, mechanical and hide important facts from them.53

Another barrier identified concerns the little time nurses have to share with the family.46,57 On the one hand, there is the high work load of nurses57 in a busy environment,46 sometimes with a shortage of nurses at certain times during the shift.79 And on the other hand, there are the restricted visits and visiting times,3,24,38,57,69 which means meetings between the nurse and the family members are short, limiting the time for interaction, communication and, in turn, the possibility to establish relationships.3,46

The environment or atmosphere of the ICU has also been identified as a problem for families,78 which may influence their willingness to relate to nurses. The ICU environment is recognised by families as strange and unfamiliar, uncomfortable80 and in some cases difficult to locate.81 The layout and location of the ICU are designed so that family members have to be on the outside, which makes their role a passive one.3 And facilities are reported as not really being suitable for waiting;25 the satisfaction of relatives with waiting rooms is low, as they are noisy, poorly lit, not cosy and cramped.4,38,71,82

As limitations of the study, we found that the concept of relationship is used as an equivalent to that of interaction and this, in turn, as an equivalent to communication, which made it difficult to locate articles and identify the themes. Therefore, we propose undertaking studies with methodological approaches that examine understanding and the complex dynamics of this relationship, rather than its explanation. In addition, there was the limitation of not being able to access 6 articles in full text, which were potentially relevant for this review. We propose making use of additional search strategies, such as inter-library loans, consultancy with specialist networks in the subject and management with expert researchers in the field. In addition, we propose extending the search in other databases, such as Embase, Ebsco and Medline.

ConclusionsThe admission of a person in a critical state of health to the ICU produces strong destructive emotions in family members such as anguish, anxiety, guilt, stress and fear that can compromise their health and even their physical, psychological and social wellbeing, with possible short, medium and long term consequences. These emotions can make the relationship between the nurse and the family difficult.

Relationship has 2 central elements, interaction and communication, as they allow for better understanding and favour the creation of empathic and trusting relationships, and this contributes to issues such as the humanisation of the ICU and can help towards strengthening projects such as the HU-CI project.

Many authors agree that there are barriers to establishing a relationship, such as no or little predisposition on the part of the nurse towards family members, the type of information given to family members, lack of understanding and empathy, indifference towards relatives, lack of time due to working conditions and regulatory systems, restricted visiting times in particular; problematic and unsympathetic communication, and an uncomfortable environment for the family.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Duque-Ortiz C, Arias-Valencia MM. Relación enfermera-familia. Más allá de la apertura de puertas y horarios. Enferm Intensiva. 2020;31:192–202.