The number of advanced practice roles in healthcare is increasing in response to several factors such as changes in medical education, economic pressures, workforce shortages and the increasing complexity of health needs of the population. The Advanced Critical Care Practitioner Curriculum, developed by the Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine in the UK (United Kingdom), enables the development and delivery of a structured education programme which can contribute to addressing these challenges. This article outlines how one university designed and implemented this programme, the first of its kind in Northern Ireland.

El número de roles de práctica avanzada en la atención médica está aumentando en respuesta a varios factores, como los cambios en la educación médica, las presiones económicas, la escasez de mano de obra y la creciente complejidad de las necesidades de salud de la población. El Advanced Critical Care Practitioner Curriculum, desarrollado por la Facultad de Medicina de Cuidados Intensivos del Reino Unido (Reino Unido), permite el desarrollo y la entrega de un programa educativo estructurado que puede contribuir a abordar estos desafíos. Este artículo describe cómo una universidad diseñó e implementó este programa, el primero de su tipo en Irlanda del Norte.

Advanced practice has gained momentum within the clinical setting in nursing and other healthcare professionals such as physiotherapists, pharmacists, and paramedics. A change to medical education and work duration, economic factors, workforce shortages and an ageing population with more complex care needs, has led to the development of the role.1,2 An issue with implementation is the diversity of the titles used, role focus, educational requirements, and regulation, leading to a lack of standardisation at both a local and international level.

Internationally, advanced nursing practice has been developed and supported by the International Council of Nurses.3 The United States of America, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand have all implemented Advanced Nursing Practice (ANP) roles4 which are often diversified by clinical specialty such as critical care. Mainland China has most recently commenced the first MSc nurse practitioner programme.5

In Europe there is still an ongoing implementation process, with a few countries establishing ANP specific educational programmes.6,7

Difficulty in definition of the role can translate into a lack of clarity of what is required to be included within education programmes to support the transition from the experienced registered nurse into the role of an ANP in Critical Care (ANPCC). Education of nurses which is evidence based and within a clearly defined scope of practice are associated with better patient survival and health outcomes.8 This supports patient safety and optimisation of care.

The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), the regulatory body for nursing in the United Kingdom (UK), recently launched a review into the advanced practice role regarding formalising regulation and scope of the role (Nursing and Midwifery Council.9 In the UK, the scope of practice in critical care is guided by the Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine10 syllabus. The guidance is for Advanced Critical Care Practitioners (ACCP), of which ANPCC is categorised, requiring the trainee to register at the beginning of their programme, culminating in membership on successful programme completion. The ANPCC role in the UK is beneficial as it provides person-centred care with continuity, whilst using an expanded skill set to deliver autonomous advanced skills such as prescribing, health assessment, diagnostics, and technical procedures such as arterial lines. More recently advanced practice has been more clearly defined as a level of care rather than an expression of technical skill.1 Until 2022 Northern Ireland was the only country in the UK without ANPCC's in practice and an educational programme or trainees, despite other countries having the role for over a decade.

Rationale for introducing the role – a Northern Ireland perspectiveIn response to this evolving landscape and progressive advances within Intensive Care Medicine, the Chief Nursing Officer commissioned the development of a career pathway for Critical Care Nursing in Northern Ireland. This strategic initiative aligned with the Delivering Care Phase 1b Critical Care11 framework, ensuring that the healthcare workforce remains adept at keeping up with the fast pace of innovation and development within the field of critical care.

The strategic document “Delivering Together”12 recognises the importance of nurturing a skilled and proficient healthcare workforce and emphasises the necessity to provide opportunities for skill development and career progression. This commitment is further reinforced in the Health and Workforce Strategy,13 which advocates for enhancing the skills and expertise of employees within the Health and Social Care Service of Northern Ireland.

The proposed framework aims to support the provision of high-quality care within critical care settings by outlining recommendations based on strategic considerations, professional standards, and the best available evidence.

A key aspect of this career pathway is the Advanced Nursing Career Path (ANCCP) role, which offers a new and innovative educational development opportunity designed to attract and retain experienced Critical Care Nurses, ensuring a robust and competent workforce capable of delivering safe, effective, person-centred. Investment in the professional growth and education of critical care nurses, aims to create a sustainable and agile workforce capable of adapting to advancements in health technology and best clinical practices. The ANCCP role can therefore serve as an impetus for the maintenance and elevation to the standards of care provided in critical care units, which should contribute to improved patient outcomes and experiences.

Overview of the programmeThe design of the programme gave careful consideration to the established regulatory frameworks10,12,14 with each compulsory module linked to the ANP framework.

- •

Critical Care – Advanced Nurse practitioner core competency 1,2

- •

Transforming practice through evidence core competency 3,4

- •

Successful leading for health and social care core competency 2,3

- •

Advanced assessment and Differential Diagnosis core competency 1,2

- •

Advanced Practice Clinical Portfolio core competency 1,2,3,4

- •

Quality improvement dissertation core competency 1,2,3,4

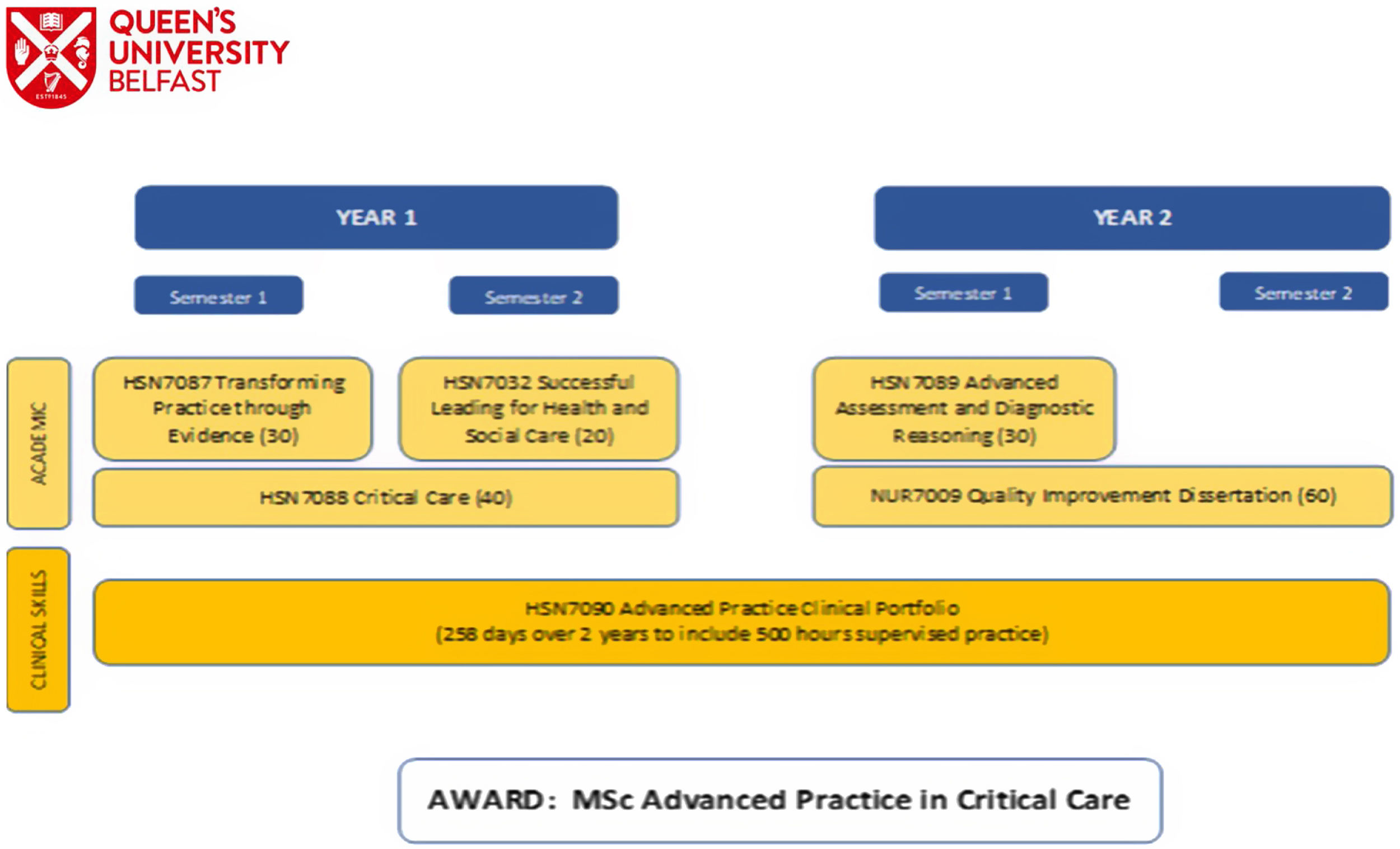

A total of five compulsory modules are taken by the trainees over two academic years alongside a clinical portfolio (Fig. 1). Each module was designed to adopt an engaging pedagogical strategy that facilitates the belief that student learning is most effective when students both construct and co-design outlooks helping individuals to make sense of their queries, issues, and ideas. This is a crucial component of the programme design enabling a scaffolding approach to learning, helping the trainees to be intrinsically motivated to collaborate and develop problem solving skills. Using a variety of platforms including flipped classrooms; face to face; tutorials; workshops; practical's; online learning; media-site lectures; podcasts and e-learning including formative quizzes a transformative trainee experience through innovative blended approaches was delivered. Thus, ensuring an inclusive, collaborative approach embedding pedagogical theories and frameworks, enabling trainees to be responsive and active learners.15

Mapped against the four pillars of advanced practice Clinical practice, Education, Research and Leadership which collectively define the scope and responsibilities of advanced practice roles in healthcare; trainees must evidence they are proficient in clinical practice, possessing advanced assessment and diagnostic abilities handling complex cases safely and confidently. The trainees engage in education and professional development contributing to the learning and development of the wider healthcare community. They are required to contribute to research and evidence-based practice by critically evaluating current practices, participating, and leading on the integration of research findings into clinical decision making thereby influencing improvements in patient care, quality improvement projects, providing leadership at an operational and strategic level.

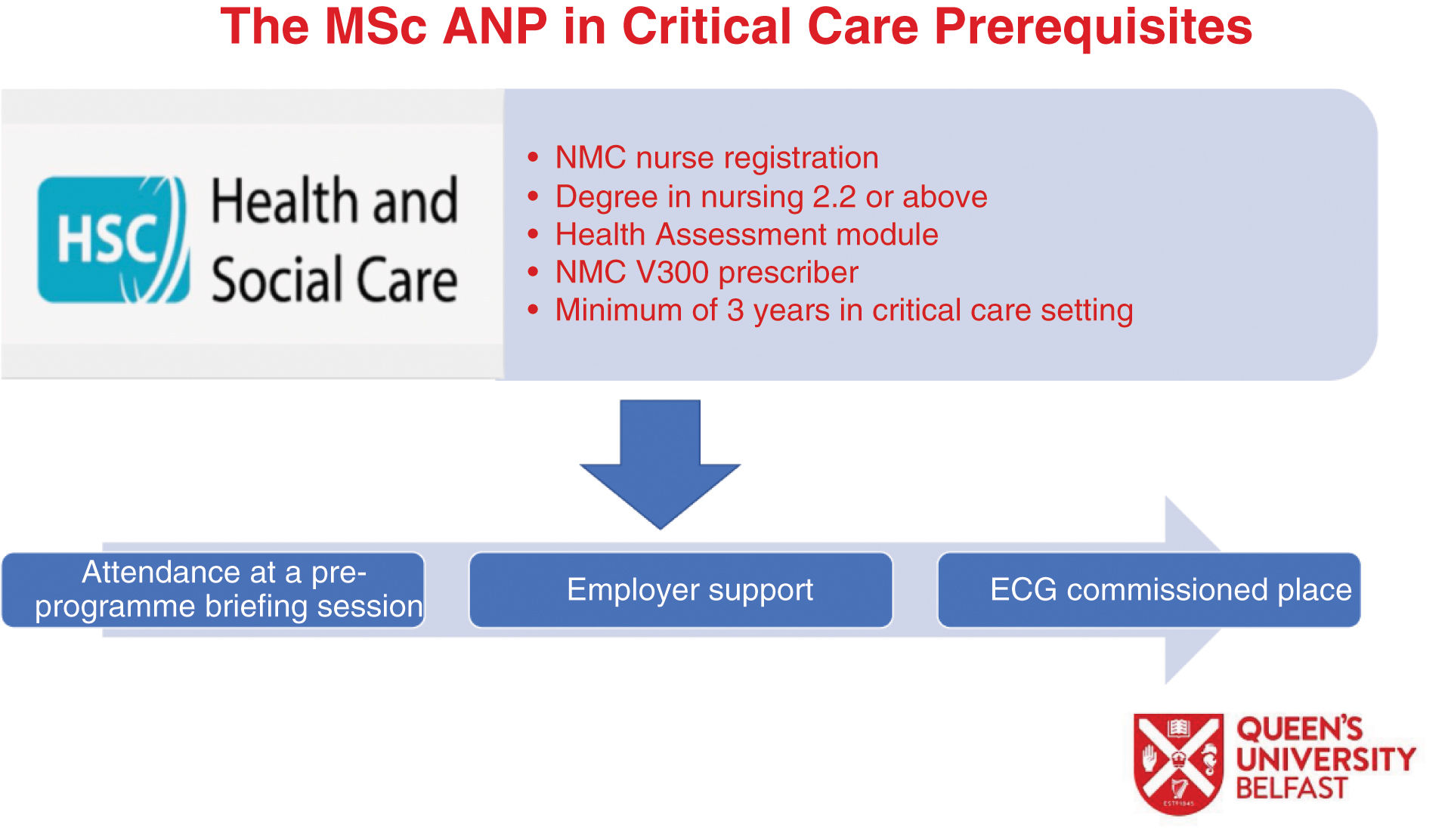

Selection and recruitmentPotential trainees needed to satisfy pre-requisites to obtain a place on the programme, as illustrated in Fig. 2. This posed challenges due to the small pool of potential applicants who satisfied this entry criterion. Potential applicants were expected to have a first degree in nursing, hold a current and substantive intensive care nursing post for at least three years, have employer support and have successfully completed the independent nurse prescribing course NMC V300 (Fig. 2). Unfortunately, the Higher Education Institution (HEI) was not involved in the selection of the trainees, which on hindsight was an opportunity missed and needs to be addressed for future cohorts.

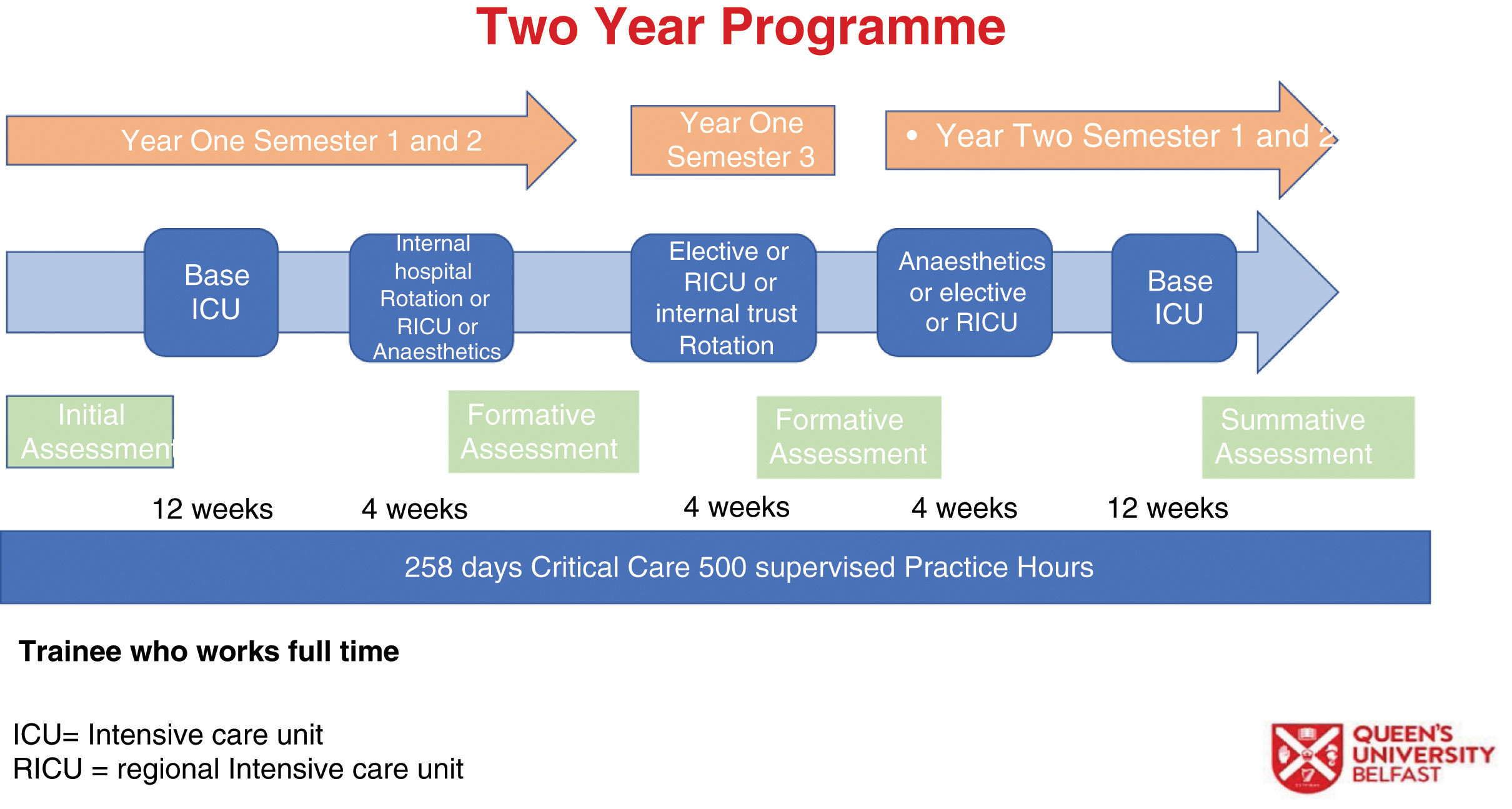

Rotational modelHistorically trainees on ANP programmes remained in their home base. However, it was recognised by the programme team that for trainees to be successful and sufficiently challenged with a breadth of experiences, they would undertake clinical attachments with other Intensive Care Units across Northern Ireland. Negotiation was needed with all stakeholders across multiple professions and geographical locations, regarding local support for the delivery and implementation of the clinical elements of the programme. Recognising, empathising, and respecting stakeholders’ positions in a challenging environment fostered a dynamic approach which resulted in a comprehensive and cohesion shared vision. Adopting practice development methodologies of high challenge, high support to nourish and encourage helped stakeholders to understand the rationale of their clinical contributions to support trainee learning and progression.16 This collaborative approach helped support the implementation of the clinical element of the programme, providing reassurance around skills competence, decision making, standard setting, and quality assurance. This element of the programme posed challenges not least how feedback would be given and shared to trainees and their supervisors (Fig. 3). Therefore, a new and innovative e-Portfolio was designed and implemented to further facilitate this.

ePortfolioThe application of theory to practice can be challenging and understanding the intricacies and aligning this approach to a progressive and constructivist paradigm enabled trainees to develop the knowledge and skills necessary to be an interactive, democratic, and autonomous practitioner, thereby supporting them to build upon reflective practice, evaluation, critique, and metacognitive awareness.17 To ensure integration in practice, trainees undertake clinical practice supported by clinical supervisors concurrently with theoretical modules. Requiring a multidimensional approach which is comprehensive, objective, and evidence knowledge, skills, and professional behaviours.18

A new and innovative ePortfolio was developed to ensure transparency of interprofessional feedback while trainees were rotated across the region. ePortfolio pedagogy is a responsive approach to foster clinically based learning and offers a flexible, adaptable portfolio which enables the building of evidence, allowing development while assessing the trainee against set proficiencies.19 Providing a mechanism to capture evidence of learning and an extension of curriculum stimulating trainee learning20 it enables trainees to understand and hypothesise the many variables that need to be incorporated to succeed in practice.21 Slade et al.22 highlight that tensions may exist for trainees regarding implications of transparency online. A lack of awareness combined with inappropriate attitudes may contribute to trainee transgressions online therefore it was essential that educational intervention assisted the trainees to understand the nuances of guidelines when applied to different practice scenarios.22 This approach enables trainees to take ownership of their own learning, promotes interdisciplinary working, embeds collaboration, increases effective problem-solving skills, which can lead to intrinsic reward.23 It helps trainees understand the multi-facetted approach required when dealing with health care issues within ever changing environments, helping them to contextualise the problems evoking a spirit of enquiry whereby trainees can strengthen their portfolios with credible evidence while delivering safe and effective care.24

Advanced Nurse Practitioner in Critical Care moduleThe core theoretical module which is Critical Care (CC) focused, this module spanned a full academic year. The content aligns with the core knowledge and basic science block on the FICM (Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine) syllabus10 alongside technology, organ donation, end of life care and patient transfer. As the seminal programme to run in Northern Ireland, the delivery of content in person was by ICU (Intensive Care Unit) doctors. The addition of ICU Scientists, Specialist Nurse in Organ Donation (SNODS) and Northern Ireland ICU transfer team (NISTAR) added a depth of learning and expertise amounting to a robust, multi-disciplinary module. Teaching came in a variety of pedagogical approaches, face to face delivery, asynchronous digital learning, podcasts and flipped classroom case presentations.25 Using the flipped classroom approach whereby the trainees presented physiology and pathophysiology alongside a clinical case study enabled them to build on the pillar of education.12 There is an expectation that ANPCCs (ANP in Critical Care) will be the educators of the future in both their own clinical setting but also role-models in a wider context, and so it is important to consolidate skills that will enable this.

To mediate the absence of ANPCC in Northern Ireland that could provide frame of reference and delivery of educational content, colleagues in Scotland and England delivered livestream master classes to the trainees via Microsoft Teams. This allowed trainees to see the expected scope of practice and become aware of the facilitators and barriers of being a practicing ANPCC.

Anatomy, physiology, and pathophysiology were delivered alongside authentic learning experiences in practice, using a systems approach to delivery each week, for example the respiratory system. An innovative component of the module delivery was the introduction of in situ simulation sessions. Queen's University Belfast has a state-of-the-art InterSim suite with a Highly Immersive Virtual Environment (HIVE) facility. Seven simulation scenarios were co-designed by the inter-disciplinary academic team and CC doctors to facilitate realism and were designed using the International Nursing Association for Clinical Simulation and Learning (INASCL) standards.26

Simulation-based education is used to replicate clinical practice settings and scenarios.27 This is appropriate for the ICU clinical setting as the cohort of patients are of high acuity and avoidance of medical error is paramount for patient safety and delivery of optimal care. Trainees were involved in a structured post- simulation de-brief using the PEARLS model,28 co-delivered by trained academic staff and clinical CC doctors. This allowed for the creation of a psychologically safe environment and micro-teaching following participation.

An example of one scenario was the assessment of a patient following an abdominal aortic aneurysm and the decision to transfer for a CT (Computed Tomography) scan. The HIVE has a projection of a CT scanner, and the trainee was immersed in the safety critical preparation and observation of an ICU patient who is intubated and undergoing a scan. Trainee feedback was that they enjoyed the simulation sessions and would like more of them, as they could perform clinical application of theory in a simulated learning environment.

Assessment of the module was done through a presentation, examination, and in situ simulation scenario. The simulation scenario was a novel approach to summative module assessment within the school of Nursing and Midwifery in the last year. It is an effective and innovative method of observing advanced health assessment and clinical decision-making skills, using authentic case-based learning.

ANPCC have a unique role in that they have a wealth of experience as a bedside nurse and can deliver evidence-based, person-centred care to a high standard. They are registered with the Nursing and Midwifery Council14 under the scope of practice as an adult nurse. However, they are now expected to expand knowledge, skills, and critical thinking to elevate their existing abilities and elevate them to include advanced assessment and management of a CC patient. This can be challenging, and it is important to recognise that there are professional, legal, and ethical aspects to the role. This is assessed via a presentation of an anonymised case study where all aspects are considered in relation to the patient and their care. Smart and Creighton29 outline that the NMC requires fundamental nursing values of the ability to practice autonomously and be both responsible and accountable for safe, person- centred care. This must be maintained through the ANPCC role, as they remain primarily registered nurses but with a now expanded scope of practice.

Moving forward: an iterative processThe first year of the ANPCC programme has run and trainees will enter their second and final year. Reflection on the first year is important for the adaptation and enhancement of the Master's degree, following feedback from the trainees, stakeholders, academic and clinical staff involved in the programme. In preparation for the next cohort changes have been made to the structure, the Advanced Health Assessment module will be moved from second year to first, alongside the CC module as per trainee feedback. The increased and continued involvement of ANPCC colleagues from the UK will continue as they are already established in both the clinical and educational delivery of the role.

A discussed earlier the stringent criteria limit the number of nurses eligible to apply for a place on the programme. It is anticipated that due to the ongoing development of a critical care pathway there will be a larger number of eligible applicants. The HEI in future will be involved in this robust selection criterion in line with that of the FICM10 recruitment guidance.

One of the key learning points from this programme design and implementation was the utilisation of networking with others in the role both from an education and clinical scope of practice. To nurture these links trainees will need to build their own ANPCC network in NI but also link in with other advanced practitioners in other disciplines.

ConclusionIn conclusion this new programme sets the foundations for CC education in Northern Ireland for those professionals who wish to progress their career in a clinical pathway. The impact of this advanced role in Northern Ireland will lead to improved patient experience, continuity of care and management. Within the clinical setting these experienced nurses will be able to demonstrate advanced skills leading to improved retention and as aspirational model for less experienced nurses that the profession seeks to recruit and retain. Excellent workplace supervision is needed and the infrastructure within in practice needs to be robust, efficient, and embedded to facilitate the trainee's development. This supervision and support in practice needs to extend beyond graduation with organisational readiness demonstrating a clear commitment to these roles being a priority. A university wide aim is to build capacity for not only continued ANPCC cohorts but the building of ANP programmes for other disciplines and allied health professionals in line with other universities in NI and the UK.

The implementation of this programme has been labour intensive and has required significant support form clinicians, academics, and the trainees. The strong partnerships that exist between the University, hospitals, and key stakeholders has ensured its success to date and will remain a key element for the success of future ANP programmes.

Ethical considerationsNo patient information is disclosed in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors state that they have no conflict of interests.