This paper presents some reflections on strategic response models, in particular the models proposed by Pache, Santos and Oliver, and it evaluates their complementarity and differences, especially regarding the interactions between decision making and the possible strategic responses to institutional demands. It is argued that the theoretical contributions of Pache and Santos can be categorized under the dimension of utility, because they can enhance the potential to operationalize and test the model. However, the reflections made in this paper not only highlight the need to take into account other external and internal factors for the study of strategic responses, but also the integration of different linkages of the decision process with strategic responses to institutional demands.

Este artículo presenta una reflexión sobre los modelos de respuesta estratégica, en particular, los propuestos por Pache, Santos y Oliver, a fin de evaluar sus complementariedades y diferencias, especialmente las interacciones entre las decisiones y las diferentes posibilidades de respuesta estratégica ante las demandas institucionales. Se argumenta que las contribuciones teóricas realizadas por Pache y Santos pueden clasificarse en la dimensión de utilidad, debido a que pueden aumentar el potencial de operacionalizar y poner a prueba el modelo. Sin embargo, este artículo pone de manifiesto la necesidad de tener en cuenta otros factores externos e internos en el estudio de las respuestas estratégicas, así como la integración de diferentes vínculos del proceso de decisión con las respuestas estratégicas a demandas institucionales.

Este artigo apresenta uma reflexão sobre os modelos de resposta estratégica, em particular, os propostos por Pache, Santos e Oliver, com o objectivo de avaliar as suas complementariedades e diferenças, especialmente das interacções entre as decisões e das diferentes possibilidades de resposta estratégica perante os pedidos institucionais. Argumenta‐se que as contribuições teóricas realizadas por Pache e Santos podem ser classificadas no âmbito da utilidade devido ao facto de poderem aumentarem o potencial de operacionalizar e pôr à prova o modelo. Porém, este artigo manifesta a necessidade de levar em consideração outros factores externos e internos no estudo das respostas estratégicas, assim como a integração de diferentes vínculos do processo de decisão com as respostas estratégicas a pedidos institucionais.

In organizational studies, particularly in institutional theory, there has been a growing interest in the strategic responses of organizations to institutional demands (Lawrence, 1999), especially those of a conflicting nature (Goodrick & Salancik, 1996; Oliver, 1991; Scott, 2005; Seo & Creed, 2002), which are broadening the limits of attention on the part of institutional theorists, which was hitherto focused on the effects of the institutional environment on structural conformity and isomorphism effects (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Meyer & Rowan, 1977; Oliver, 1991; Zucker, 1977). Using these frameworks as a basis, Pache and Santos (2010) built a model of organizational responses to answer the question “How does an organization respond when influential stakeholders hold contradicting views about its appropriate course of action?” (Pache & Santos, 2010, p. 456). The authors affirm that even though current models recognize that compliance with conflicting institutional demands is problematic, and point to alternative response strategies, they treat organizations as unitary players developing strategic responses to external pressures and largely ignore the role of intra‐organizational dynamics, which Pache and Santos included in their model to increase its predictive power, and to identify with more precision the conditions under which specific response strategies are used.

Even though these authors made a contribution to the model developed by Oliver (1991), organizational theorists have already acknowledged the intra‐organizational dynamics by recognizing the fragmentation of complex organizations (Flingstein, 1990; Lawrence and Lorsh, 1967 in Kostova & Zaheer, 1999); furthermore, Kostova and Zaheer (1999) in their study of Multinationals Enterprises identify the need for organizational subunits to achieve internal legitimacy within the organization, in addition to legitimacy with the external environment.

Although Pache and Santos (2010) critique previous models because of their lack of integration of institutional field and intra‐organizational levels, the authors put aside some external and internal factors that also play predominant roles in the organizations’ strategic response to institutional demands, such as media exposure and the size of the organizations; they justify these limitations as an effort to achieve parsimony. Among the external factors is media exposure, which, having taken on increased significance in assigning importance to issues, plays a role in confirming or eroding the legitimacy of individual firms, and by doing so, affects the organization's responses to institutional pressures (Greening & Gray, 1994; Gupta, 2009). On the other hand, an important internal factor is the size of the organizations, because by virtue of their size and visibility, large organizations are subject to considerable attention from state, media and professional groups, which is a strong incentive to take actions to ensure their legitimacy (Mintzberg, 1983 in Goodstein, 1994).

Moreover, with their claim of the predictive power of the model and a systematic understanding of the influences of conflicting institutional pressures, they assume that all strategic responses are the result of a rational process of decision making (March & Simon, 1958; Simon, 1979), which can be a sequence of decomposed stages that converge on a solution (Langley, Mintzberg, Picher, Posada & Saint‐Macary, 1995), in this case responding to social and legal institutional demands (Simon, 1979). Nevertheless, organizational decision making is a socially interactive process (Cyert & March, 1963; Langley et al., 1995), which makes it difficult to follow what is simply a rational decision making process.

In conclusion, it is argued here that the contribution made by the authors to the model developed in the first instance by Oliver (1991) is basically the addition of the role of intra‐organizational dynamics, and although it does not significantly modify the logic of the pre‐existing model, it offers better comprehension of the different elements that can affect organizations’ strategic responses to conflicting institutional demands, making it a contribution more of utility than of originality. However, there is no empirical evidence of the predictive power of the complete model, which leaves the need of empirical studies to assess each of the propositions and the model.

In formulating these arguments, this paper is divided into three sections. First, it builds on the concepts of institutional demands and strategic responses to identify the conceptual bases of the strategic response models. Second, it evaluates the contributions of Pache and Santos’ model to the study of different decision making processes behind the organizations’ selection of strategic responses to institutional demands. Third, it identifies some other external and internal factors that also play predominant roles in the organizations’ strategic response to institutional demands that can change the predictive responses identified by Pache and Santos (2010), and concludes with theoretical implications.

2Internal dynamics of organizational responses to conflicting institutional demandsThis paper highlights two main concepts that are present in the mainstream literature of institutional theory that has focused on strategic decision making, and represent the basis of the models developed by Pache and Santos (2010) and Oliver (1991). These concepts are institutional demands and strategic responses.

With the aim of evaluating the complementarities and differences of the models of Pache and Santos (2010) and Oliver (1991), the sections presented below introduce the concepts of institutional demands, strategic responses, and the description of the predictors of the strategic responses proposed by Oliver (1991) and Pache and Santos (2010).

2.1Institutional demandsResearchers in institutional theory have recognized the complexity of institutional environments because of the different demands that they can impose on organizations; Scott (2005) describes it as a growing awareness of the multiple and varied facets of the environment; furthermore, he states that because of changes in information technology, as well as the increasing mobility of capital, labor, ideologies, beliefs, consumer preferences, and fads, a single organization is more likely to operate simultaneously in these numerous institutional environments. Meyer and Rowan (1977) argue that the survival of some organizations depends more on managing the demands of internal and boundary‐spanning relations, while the survival of others depends more on the ceremonial demands or myths of highly institutionalized environments, conditional on their necessity of institutional resources; however, they recognize that institutionalized myths differ in their rules and description of standards that should be used to evaluate outputs.

In the same way, Oliver (1991) notes that organizations are often confronted with conflicting institutional demands, or with inconsistencies between institutional expectations and internal organizational objectives, which lead them to respond according to their resource dependencies of the constituent. Furthermore, Seo and Creed (2002) in their identification of institutional contradictions highlighted the inter‐institutional incompatibilities, which are derived from a context of multiple, interpenetrating levels and sectors; as a result of these incompatibilities the organizations’ conformity to certain institutional arrangements within a particular level or sector may cause conflicts or inconsistencies with institutional arrangements of different levels or sectors.

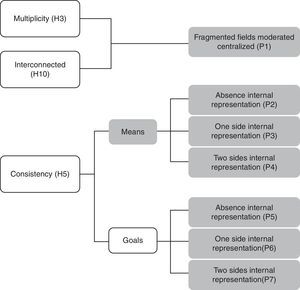

Similarly, Pache and Santos (2010) use the term institutional demands in their model to refer to these various pressures for conformity exerted by institutional referents on organizations in a given field. They are especially focused on conflicting institutional demands defined as the antagonisms in organizational arrangements required by institutional referents, which Oliver (1991) refers to as multiplicity.

2.2Strategic responseWhen environments are more conflictive or ambiguous, organizations have a greater opportunity for strategic behavior (Scott, 2005); this behavior is called institutional strategy by Lawrence (1999), who states that institutional strategy demands the ability to articulate, sponsor and defend particular practices and organizational forms as legitimate or desirable, rather than the ability to enact already legitimated practices or leverage existing social rules.

Oliver (1991) states that depending on the dependence of organizations on institutional resources, organizations exercise different degrees of resistance and activeness to respond to external constraints and demands. She proposes that organizational responses will vary from conforming to resistant, from passive to active, from preconscious to controlling, from impotent to influential, and from habitual to opportunistic, depending on the institutional pressures toward conformity that are used on organizations. However, organizations’ strategic interest also plays an important role in the selection of alternative ways to deal with institutional uncertainty (Goodrick & Salancik, 1996).

In these strategic responses, the role of intra‐organizational dynamics has been acknowledged by organizational theorists, who recognize the fragmentation of complex organizations (Flingstein, 1990; Lawrence & Lorsh, 1967 in Kostova & Zaheer, 1999), even though traditionally, organizational legitimacy is defined as the organization's conformity with institutionalized rules and practices being vital for organizational survival and success (Meyer & Rowan, 1977). Kostova and Zaheer (1999) in their work with Multinationals Enterprises, identified the need for organizational subunits to achieve internal legitimacy within the organization, in addition to legitimacy with the external environment, because organizational legitimacy can be shaped by not only the complexity of the environment's institutional characteristics, but also by the complexity of the organization's characteristic.

Likewise, Jarzabkowski (2004) studied recursive and adaptive strategic responses, recognizing the multiple levels that these strategies cover, from macro‐institutional and competitive contexts to within‐firm levels of analysis to individual cognition. She defines recursiveness as the socially accomplished reproduction of sequences of activity and action, because the actors involved possess a negotiated sense that one template from their repertoire will address a new situation; and adaptation is defined as the varying degrees of change from incremental adjustment to radical reorientation. Jarzabkowski (2004) also recognized the multiplicity of the institutional environments (macro‐institutional) and relates the strategic responses depending on the level of formalization of the institutional environment.

Finally, Pache and Santos (2010) establish three levels of institutional formalization. First, centralization, which is characterized by a well‐structured field with the presence of dominant players at field level that support and enforce prevailing logics. In contrast, decentralized fields are poorly formalized and characterized by the absence of dominant players with the ability to constrain organizations’ behaviors. Pache and Santos claim that the third level of formalization presents the most complex fields for organizations to deal with; the moderately centralized fields, which are characterized by the competing influence of multiple and misaligned players whose influence is not dominant, yet is potent enough to be imposed on organizations. They propose that a key element affecting response mobilization of organizations is whether or not the different sides of the conflicting institutional demands present in moderately centralized fields are represented internally.

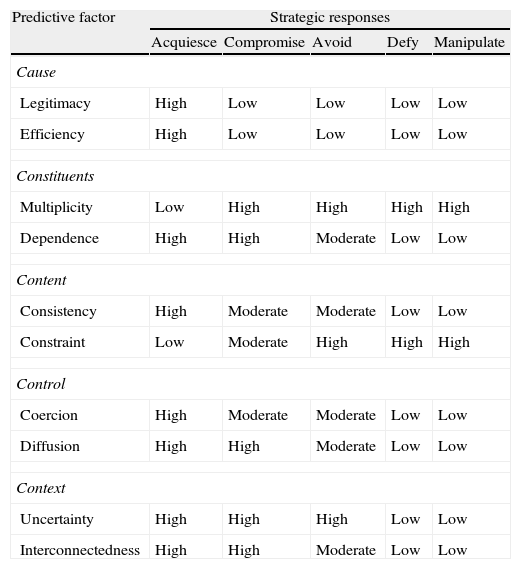

2.3Predictors of strategic responsesPache and Santos (2010) built their model on Oliver's model, which proposes five strategic responses to five institutional factors, which are divided into ten dimensions, varying the active agency of the organization from passivity to active resistance to institutional pressures. Oliver (1991) develops this preliminary conceptual framework for predicting the occurrence of alternative strategic responses by comparing the similarities and differences between institutional and resource dependence theories. Specifically, the assumptions about organizational behavior that include the potential for variation in the degree of choice, awareness, proactiveness, influence and self‐interest that organizations exhibit in response to institutional pressures.

In her model, Oliver (1991) defines five institutional factors that exercise pressures in organizations: (i) cause refers to the expectations or intended objectives that emphasize external pressures for conformity, generally in terms of legitimacy and economic efficiency for the organizations; (ii) constituents include the state, professions, interest groups and the general public, imposing a multiplicity of laws, regulations and expectations on organizations, depending on their dependency on these constituents; (iii) content refers to the consistency of the pressures with organizational goals, and with the decision making constraints enforced on the organization; (iv) control refers to two main means by which institutions exert pressures on organizations, and these consist of legal coercion imposed by government or voluntary diffusion, because institutional demand has been already diffused by other organizations in the field; (v) finally, environmental context, which is constituted by uncertainty in the anticipation and prediction of future and interconnectedness among the players of the organizational field.

On the other hand, the five types of strategic responses proposed by Oliver (1991) are: (i) acquiescence, which refers to organizations’ adoption of arrangements required by external institutional constituents, and this can be used by organizations when there is no conflict present between institutional demands; (ii) compromise, which is defined as the attempt by organizations to achieve partial conformity with all institutional expectations by trying to balance, pacify or bargain with external constituents; (iii) avoidance is the organizational attempt to prevent the necessity to conform with institutional pressures; (iv) defiance refers to the open rejection of at least one of the institutional demands; (v) manipulation refers to the active attempt to alter or exert power over the content of institutional requirements.

The strategic responses depending of the predictor factor hypothesized by Oliver (1991) are outlined in Table 1.

Institutional antecedents and predicted strategic responses.

| Predictive factor | Strategic responses | ||||

| Acquiesce | Compromise | Avoid | Defy | Manipulate | |

| Cause | |||||

| Legitimacy | High | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Efficiency | High | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Constituents | |||||

| Multiplicity | Low | High | High | High | High |

| Dependence | High | High | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Content | |||||

| Consistency | High | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Constraint | Low | Moderate | High | High | High |

| Control | |||||

| Coercion | High | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Diffusion | High | High | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Context | |||||

| Uncertainty | High | High | High | Low | Low |

| Interconnectedness | High | High | Moderate | Low | Low |

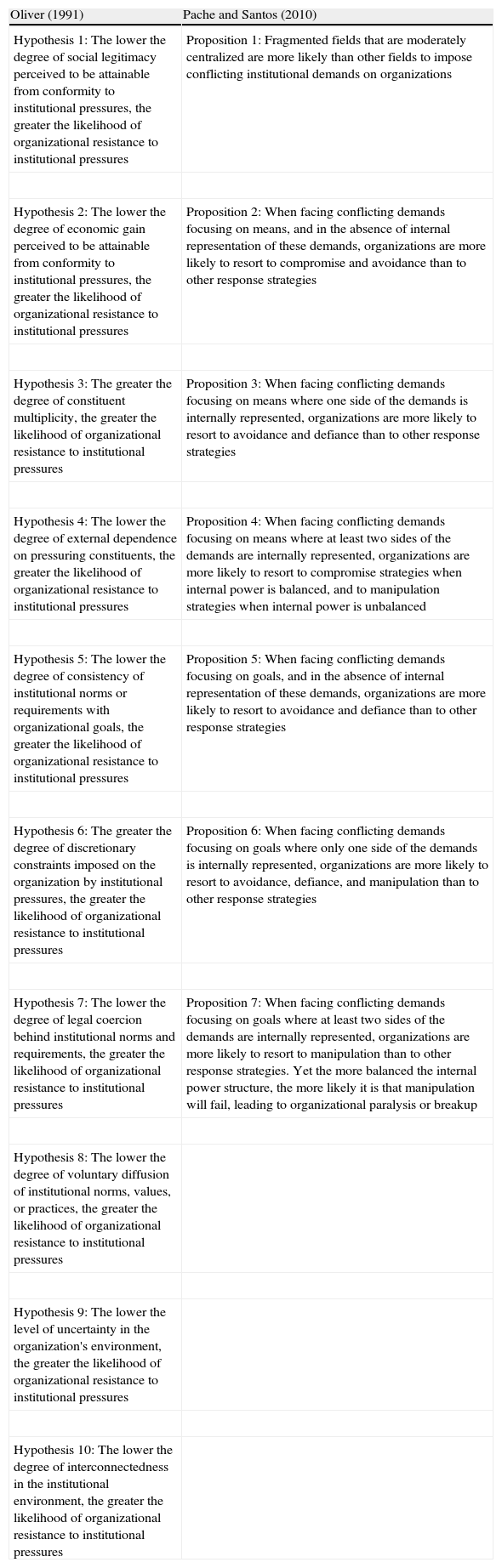

A comparative analysis of the hypothesis generated by Oliver (1991) and Pache and Santos (2010) was developed to identify the contributions made by Pache and Santos to the growing literature in organizational responses to conflicting institutional demands, and more specifically to the model developed by Oliver (1991), by detecting relations and dissimilarities between the two models (Table 2).

Oliver and Pache and Santos hypothesis and propositions.

| Oliver (1991) | Pache and Santos (2010) |

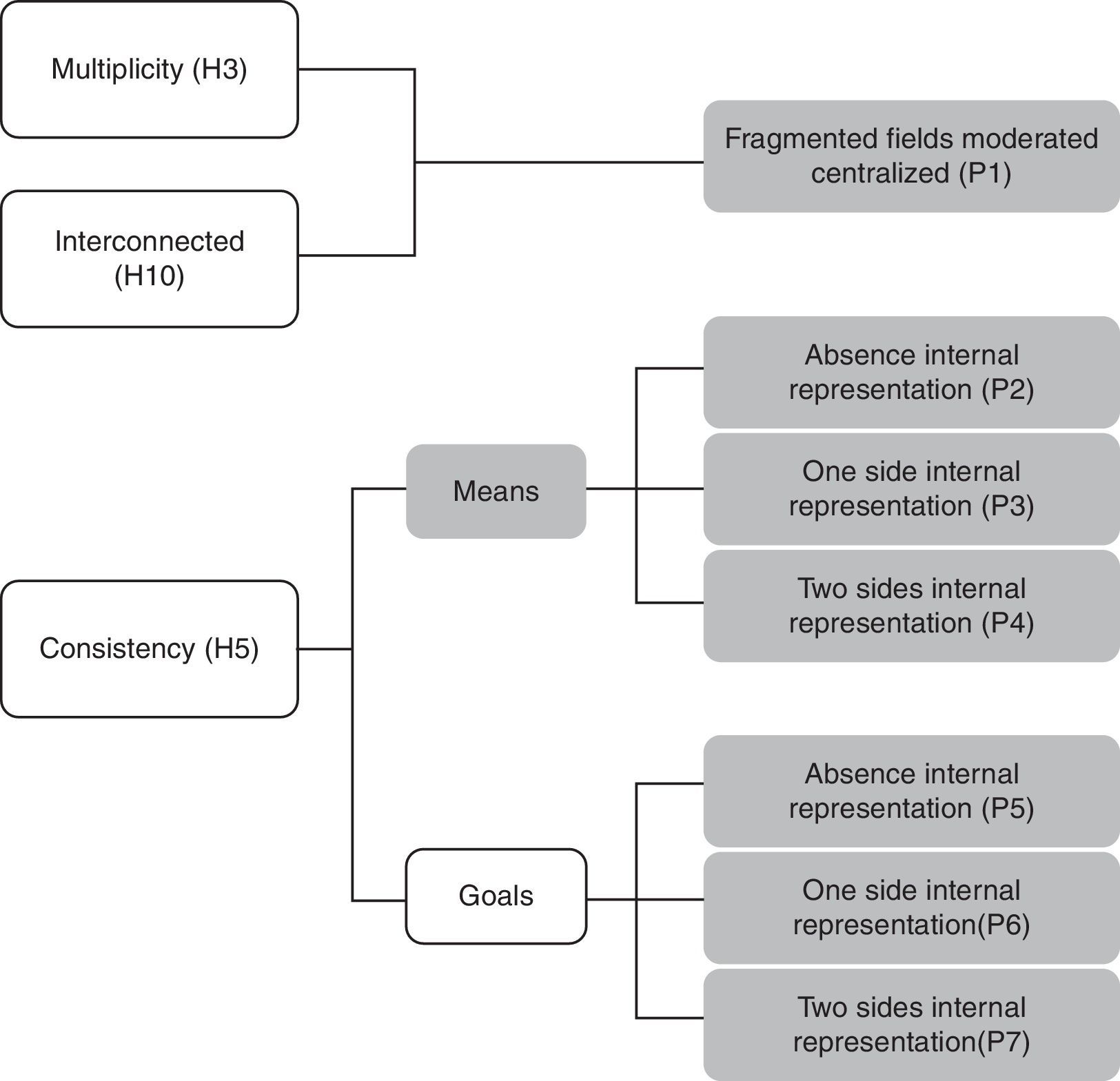

| Hypothesis 1: The lower the degree of social legitimacy perceived to be attainable from conformity to institutional pressures, the greater the likelihood of organizational resistance to institutional pressures | Proposition 1: Fragmented fields that are moderately centralized are more likely than other fields to impose conflicting institutional demands on organizations |

| Hypothesis 2: The lower the degree of economic gain perceived to be attainable from conformity to institutional pressures, the greater the likelihood of organizational resistance to institutional pressures | Proposition 2: When facing conflicting demands focusing on means, and in the absence of internal representation of these demands, organizations are more likely to resort to compromise and avoidance than to other response strategies |

| Hypothesis 3: The greater the degree of constituent multiplicity, the greater the likelihood of organizational resistance to institutional pressures | Proposition 3: When facing conflicting demands focusing on means where one side of the demands is internally represented, organizations are more likely to resort to avoidance and defiance than to other response strategies |

| Hypothesis 4: The lower the degree of external dependence on pressuring constituents, the greater the likelihood of organizational resistance to institutional pressures | Proposition 4: When facing conflicting demands focusing on means where at least two sides of the demands are internally represented, organizations are more likely to resort to compromise strategies when internal power is balanced, and to manipulation strategies when internal power is unbalanced |

| Hypothesis 5: The lower the degree of consistency of institutional norms or requirements with organizational goals, the greater the likelihood of organizational resistance to institutional pressures | Proposition 5: When facing conflicting demands focusing on goals, and in the absence of internal representation of these demands, organizations are more likely to resort to avoidance and defiance than to other response strategies |

| Hypothesis 6: The greater the degree of discretionary constraints imposed on the organization by institutional pressures, the greater the likelihood of organizational resistance to institutional pressures | Proposition 6: When facing conflicting demands focusing on goals where only one side of the demands is internally represented, organizations are more likely to resort to avoidance, defiance, and manipulation than to other response strategies |

| Hypothesis 7: The lower the degree of legal coercion behind institutional norms and requirements, the greater the likelihood of organizational resistance to institutional pressures | Proposition 7: When facing conflicting demands focusing on goals where at least two sides of the demands are internally represented, organizations are more likely to resort to manipulation than to other response strategies. Yet the more balanced the internal power structure, the more likely it is that manipulation will fail, leading to organizational paralysis or breakup |

| Hypothesis 8: The lower the degree of voluntary diffusion of institutional norms, values, or practices, the greater the likelihood of organizational resistance to institutional pressures | |

| Hypothesis 9: The lower the level of uncertainty in the organization's environment, the greater the likelihood of organizational resistance to institutional pressures | |

| Hypothesis 10: The lower the degree of interconnectedness in the institutional environment, the greater the likelihood of organizational resistance to institutional pressures |

Two main factors that are highlighted in the model of Pache and Santos (2010) are the nature of the demands and the internal representation, which they claim affect the mobilization of various response strategies by organizations that face conflicting institutional demands. To support their propositions, the authors used as empirical evidence the results from different studies made by other authors (Scott, 1983, Westphal & Zajac, 1994, Greenwood & Hinings, 1996, Montgomery & Oliver, 1996, Glynn, 2000 in Pache & Santos, 2010), except for propositions 5 and 6, which have no empirical evidence to support the authors’ claims.

The authors state that an organization's response to conflicting institutional demands is a function of the nature of these demands, which they divided into ideological and functional levels. The ideological levels are related with the goals of the organization, defined as expressions of the core system of values and references of organizational constituencies and for this reason they are not easily challenged or negotiable. Oliver (1991) also includes the consistency of pressures with organizational goals as one of the dimensions in the institutional factor of content, which is tested in hypothesis 5. In contrast, Pache and Santos defined functional and process demands as material and peripheral; therefore, this type of demands is potentially flexible and negotiable.

On the other hand, Pache and Santos (2010) argue that internal groups play an important role in interpreting and enacting the institutional demands exerted on organizations, as well as in making decisions in the face of these institutional constraints. They emphasize the importance of understanding how the different sides of the institutional are represented internally: one‐side representation, multiple‐side representation, or the absence of representation. Furthermore, the authors claim that the internal dimension allows the identification of intra‐organizational political processes that affect organizational responses to institutional pressures.

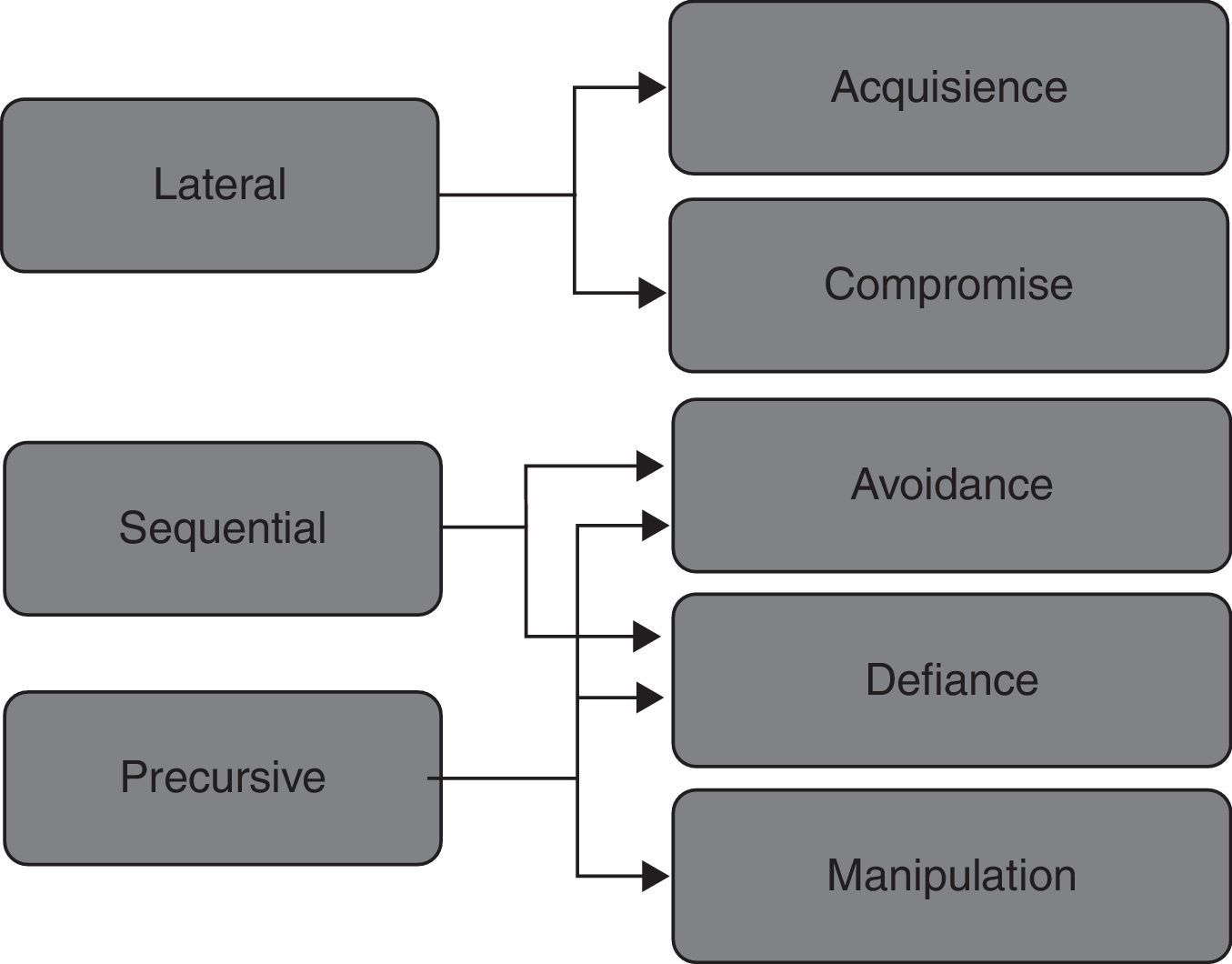

Fig. 1 illustrates the relation between the hypothesis developed by Oliver (1991) and the propositions of Pache and Santos (2010). It shows that the nature of the demands and internal representation are merely expanding the factors proposed in Oliver's model.

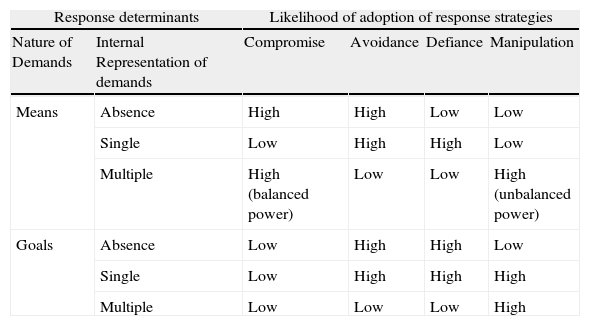

The authors also built on Oliver's strategic responses, using four of the five categories established by Oliver (1991), not including acquiescence, because they are framework under strategic responses to conflicting institutional demands attempting to answer the question: “How does an organization respond when influential stakeholders hold contradicting views about its appropriate course of action?” (Pache & Santos, 2010, p. 456) (Table 3). Even though acquiescence is an organizational strategic response to institutional demands, it does not imply conflicting demands or inconsistencies between institutional expectations and inter‐organizational objectives (Oliver, 1991).

A model of responses to conflicting institutional demands.

| Response determinants | Likelihood of adoption of response strategies | ||||

| Nature of Demands | Internal Representation of demands | Compromise | Avoidance | Defiance | Manipulation |

| Means | Absence | High | High | Low | Low |

| Single | Low | High | High | Low | |

| Multiple | High (balanced power) | Low | Low | High (unbalanced power) | |

| Goals | Absence | Low | High | High | Low |

| Single | Low | High | High | High | |

| Multiple | Low | Low | Low | High | |

To analyze the contributions of Pache and Santos, it is important to understand that despite the fact that it is possible to make an important theoretical contribution by simply adding or subtracting factors from an existing model, this may be insufficient to substantially alter the core logic of the existing model. One way to demonstrate the value of a proposed change is to identify how this change affects the accepted relationships between the variables (Whetten, 1989).

Furthermore, Corley and Gioia (2011) claim that the contributions can be assessed within the dimension of originality or utility, originality representing either an incremental, or a more revelatory or surprising advance in understanding. Contributions are incremental when they help to develop a progressive advance in the understanding of management and organizations; in contrast, revelatory is when the contribution reveals what had not otherwise been seen, known or conceived. On the other hand, utility contributions can be divided into scientific and practical. Scientific utility is perceived as an advance that improves conceptual rigor or the specificity of an idea and/or enhances its potential to be operationalized and tested, whereas practical utility is seen as arising when theory can be directly applied to the problems practicing managers and other organizational practitioners face (Corley & Gioia, 2011).

Within this framework, the contribution made by the authors to the model developed in the first instance by Oliver (1991) is basically the addition of the role of internal representation or intra‐organizational dynamics, although it does not significantly modify the logics of the pre‐existing model, and gives a better comprehension of the different elements that can affect organizations’ strategic responses to conflicting institutional demands.

In conclusion, when assessing the theoretical contribution of the authors within the dimensions of originality and utility, their contributions can better be categorized under the dimension of utility, since it can enhance the potential of operationalizing and testing the strategic response model.

4Beyond internal dynamicsOverall, Pache and Santos have focused their model on what they call the nature of demands (goals and means) and internal representation of the institutional demands; however, there are some external and internal factors that also play predominant roles in organizations’ strategic response to institutional demands, and which can change the predictive responses identified by these authors.

For example, there has been an important increase in the public exposure of business via television, radio, newspapers, magazines, films, books and social media, giving the media a significant role in assigning importance to issues and exposing gaps between business practices and society's expectations, which can confirm or damage the legitimacy of organizations, and by doing so it exerts pressure on organizations to conform to public influence (Greening & Gray, 1994).

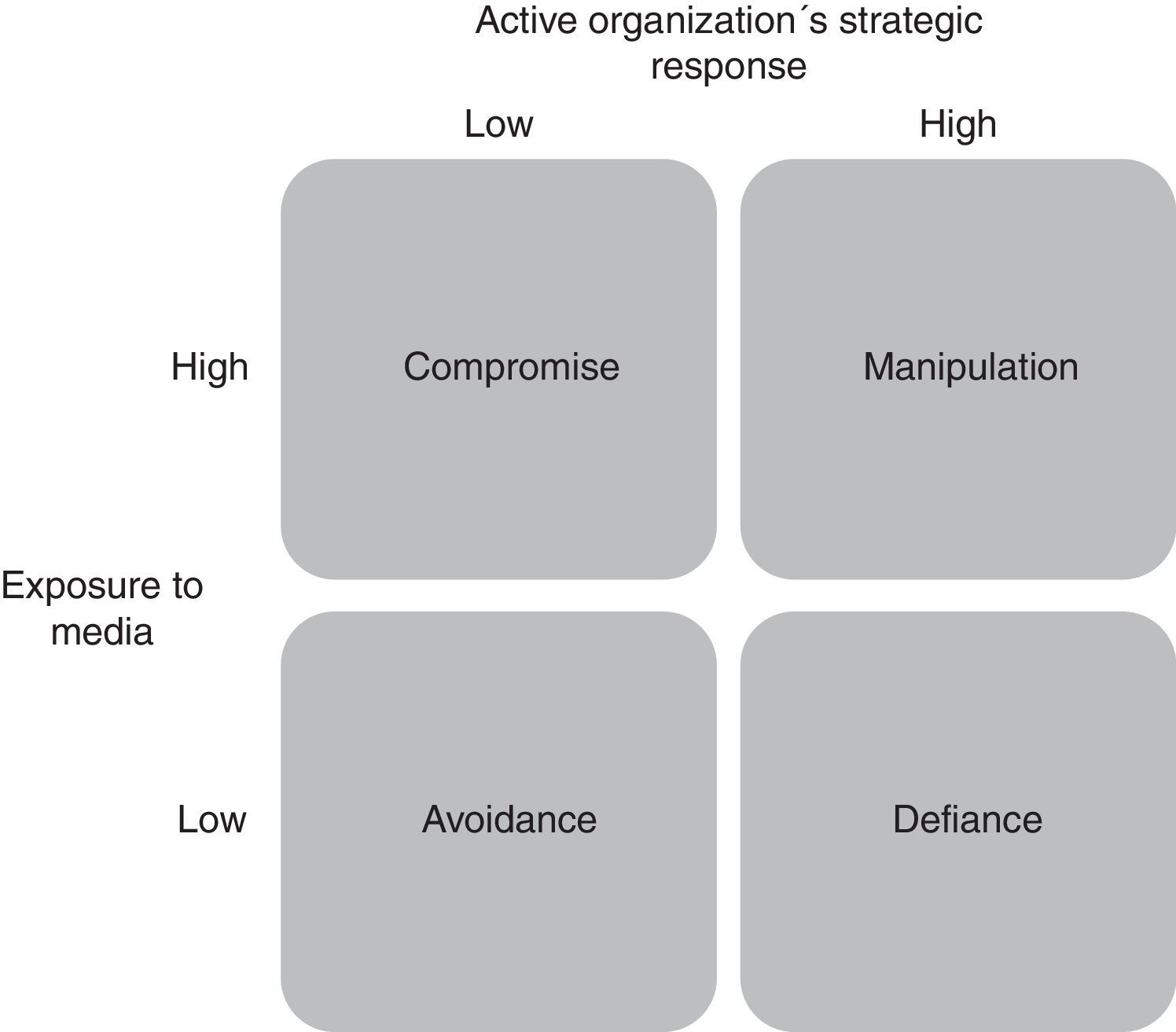

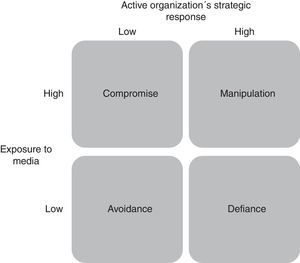

Even if the organizations have internal representation of the institutional demands or not, their exposure to media will affect their strategic responses. Nowadays, the media affect organizations and their actions, especially the social media, that can affect the consumers’ perceptions about a firm, and the strategic responses of organizations (Gupta, 2009); however, organizations can use the media to advance their own agendas, manipulating it through strategic response (Greening & Gray, 1994). This is illustrated in Fig. 2, where if organizations are more exposed to media, they are under greater pressure to compromise, balancing the multiple institutional demands to achieve parity among their different interests. However, organizations’ most active response is to use the media to change the institutional demands in their favor. Also, if exposure to media is not high, organizations can avoid the institutional demands or openly challenge them.

These predicted responses differ from the Pache and Santos model, which establishes that organizations have a low likelihood of using compromise when they are facing conflicting goal‐related institutional demands; however, if these organizations have a high exposure to media, they could use this strategic response to maintain their legitimacy.

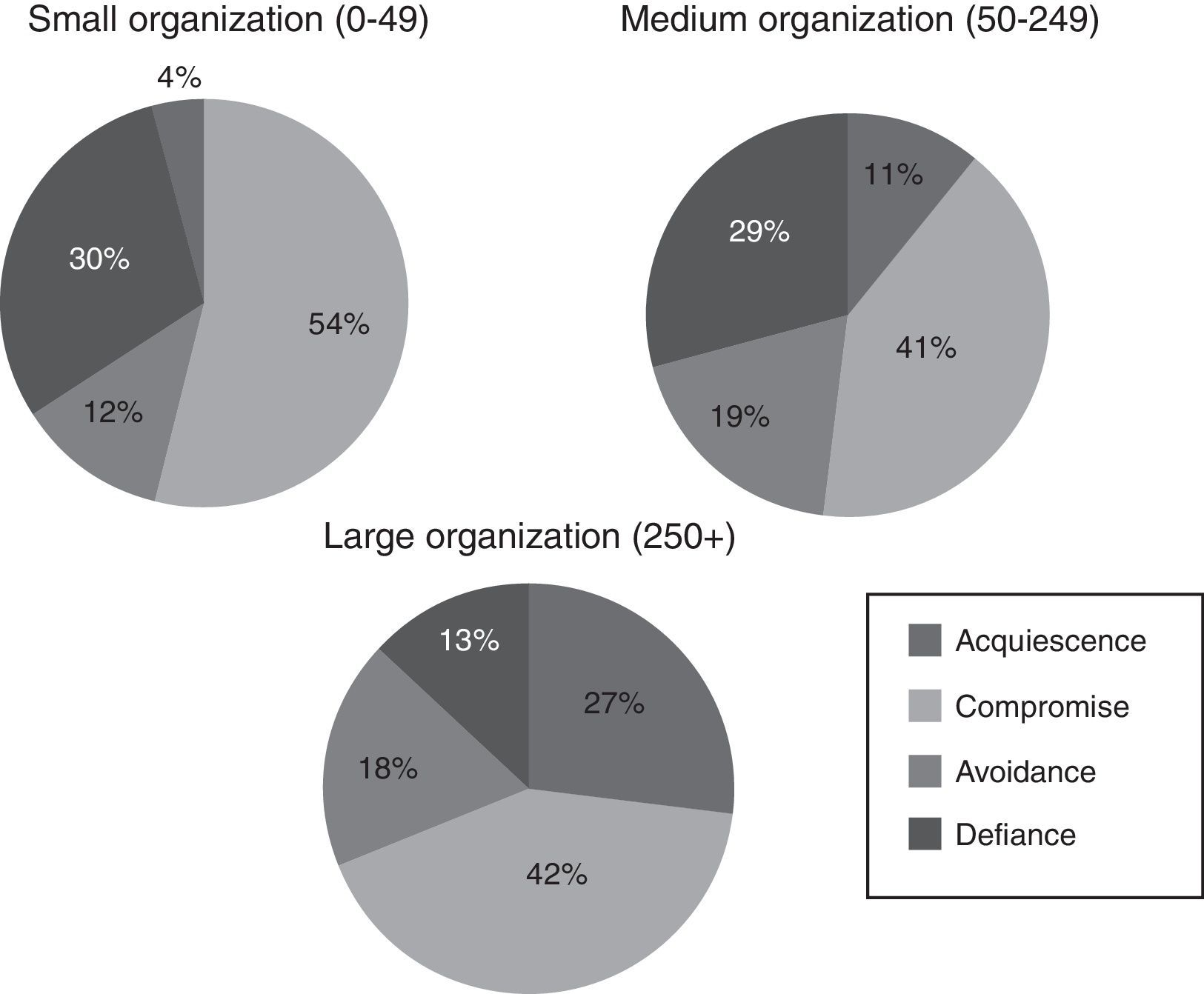

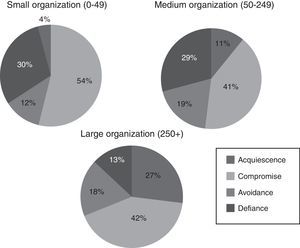

On the other hand, because large organizations are visible and accountable to various constituencies, they have a strong incentive to take actions to ensure their legitimacy (Goodstein, 1994); furthermore, size increases the complexity of internal relations (Meyer & Rowan, 1977), affecting their decision making process. This factor has been studied by Goodstein (1994) who, using Oliver's framework of institutional factors, included size under the cause factors, determining that the greater the size of an organization, the greater its level of acquiescence responses to institutional pressures, and furthermore that compromise is the strategy more used by organizations of all sizes (Fig. 3). Pache and Santos (2010), however, consider this strategic response less likely to be adopted.

Furthermore, Pache and Santos (2010) assert that their model offers a richer and potentially more relevant account of how organizations respond to conflict in institutional prescriptions, claiming that it has more precise predictive power by increasing the systematic understanding of the influences of conflicting institutional pressures.

However, with their claim of the predictive power of the model, they assume that all strategic responses are the result of a rational process of decision making, which can be a sequence of decomposed stages that converge on a solution (Langley et al., 1995), in this case responding to contradictory institutional demands. Though organizational decision making is a socially interactive process (Langley et al., 1995) where organizations have to deal with problematic preferences, because of their difficulty in assigning a set of preferences to the decision situation, in addition to the variance in the amount of time and effort required by the participants to solve the situation. As a result of this, the boundaries of the organization are uncertain and changing, and the audiences and decision makers for any particular kind of choice also change (Cohen, March & Olsen, 1972); this impossibility of isolating the decision making processes from one another and from the dynamics of the organization and institutions (Langley et al., 1995) makes it difficult to follow a simply rational decision making process.

One of the difficulties understanding how these responses occur in organization is the use of decision (response) as a primary unit of analysis, because decisions interact with one another (Langley et al., 1995), in the process of dealing with different internal and external demands, in the same or different moments of time.

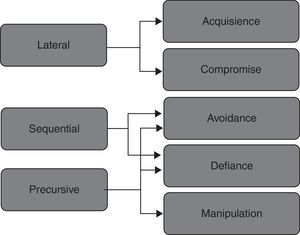

Langley et al. (1995) established three main categories of linkages in the decision making processes. First, sequential linkages defined as interrelationships between different decisions concerning the same demand at different points in time. Then, lateral linkages that refer to decisions are related with different demands at the same time, because they share resources, or share the same interpretation of the world (logic), that can be associated with the internal representation of the institutional demands. Finally, precursive linkages, which can be found when a decision one demands can critically affect the premise for subsequent decisions on a variety of other issues.

Analysing the type of linkages and the strategic responses to institutional demands, it is apparent that sequential linkages are the result of institutional demands that are not fully addressed by an organization; thus it becomes a recurrent issue to be solved by the organization. This situation can be the result of the use of avoidance and defiance strategic responses. On the other hand, when players involved in the process share the same logic (lateral linkage) they are more likely to choose a strategy acquiescence; however, when different demands with different logics share resources without needing a large investment in new resources and capacities to deal with them, organizations could implement a compromise strategic response. Finally, organizations with the resources and capabilities already clearly developed and built consequently of previous decisions (precursive linkages), are more difficult to adapt new logics and invest in the process and the resources that this implies, as a result, the most likely strategic responses of these organizations could be avoidance, defiance and manipulation (Fig. 4).

Integrating the different linkages of the decision process developed by Langley et al. (1995) with strategic responses, the understanding of the type of decision making process behind the organizations’ selection of strategic responses to institutional demands can be improved.

5ConclusionsDifferent authors have studied the reasons that organizations do not respond uniformly to institutional pressures, but rather generate different strategic responses. Oliver (1991) contributed to this analysis by focusing the external characteristics of institutional demands which pressure strategic responses from organizations. Pache and Santos (2010) building on Oliver's model, add the analysis of internal representation of institutional demand to this model. Their core argument is that the nature of the institutional conflict interacts with the degree of internal representation to shape the experience of conflicting demands and influence the strategies mobilized by organizations.

The question that can arise is why it is interesting to analyze Pache and Santos’ model. The answer could be that despite the fact that Pache and Santos’ paper is recent, the number of times it has been cited (52 citations in ISI Web of Knowledge) in the business and organization journals with higher impact factor in the last five years, such as: Academy of Management Journal, Academy of Management Annals, organization studies, Academy of Management Review, Administrative Science Quarterly, Journal of Management Studies and Strategic Organizations, shows the interest of organizational researchers in the topic, which has been used in the study of new institutional perspectives such as institutional change (Smets, Morries & Greenwood, 2012), institutional logics (Cloutier & Langley, 2013; Pache & Santos, 2013), institutional work (Clark & Newell, 2013) and institutional entrepreneurship (Pache & Chowdhury, 2012).

Pache and Santos (2010) claim that the role of intra‐organizational dynamics in organizations’ strategic responses to institutional demands has gone unnoticed in previous research; however, it has already been acknowledged by organizational theorists such as Kostova and Zaheer (1999), who recognize the fragmentation of complex organizations, and Jarzabkowski (2004), who studies the multiple levels of strategic responses to different institutional environments with diverse levels of formalization.

The contribution made by the authors to the model developed in the first instance by Oliver (1991) is basically the addition of the role of intra‐organizational dynamics, and although it does not significantly modify the logics of the pre‐existing model, it does offer a better comprehension of the different elements that can affect organizations’ strategic responses to conflicting institutional demands, which is why this paper categorizes this contribution as a utility contribution. However, it is argued that some external and internal factors which also play predominant roles in organizations’ strategic response to institutional demands, such as media exposure and organizational size, were excluded from their model in an attempt to achieve parsimony.

Finally, Pache and Santos (2010) assume that all strategic responses are the result of a rational decision making process; however, the impossibility of isolating the decision making processes from one another and from the dynamics of the organization and institutions (Langley et al., 1995) makes it difficult to follow simply a rational decision making process. For this reason this paper proposes the integration of the different linkages of the decision process developed by Langley et al. (1995) with strategic responses (Oliver, 1991; Pache & Santos, 2010) to attempt to improve the understanding of the type of decision making process behind organizations’ selection of strategic responses to institutional demands. However, some further empirical research is necessary to validate this propose.

Conflict of interestThe author declare no conflict of interest.