The purpose of this study is to explore the main differences in key variables of winemaking companies in view of their consideration as a family business in Spain. Using a database of 520 wineries with the main variables used in the literature, this paper analyses the differences between being a family or a non-family winery on the performance, size and structure of debt. The companies were classified as family or non-family then a means test was performed for all key variables between both groups. This study suggests that there are significant differences between family and non-family businesses in the return on assets (ROA) and in the operating margin, which are higher in the case of companies classified as family businesses and in the relative debt and debt ratio, which are higher in companies considered to be non-family. The remaining variables are statistically equal. Better margins in family companies could be due to advantages in the prices derived from the products or brands offered or lower agency costs that may lead to an improvement in management costs, which explains such differences. In addition, the lower risk exposure that would lead family businesses to opt for less risky leverage formulas that would lead to increased long-term financing could explain why these advantages are not reflected in the return on equity (ROE).

El propósito de este estudio es explorar las principales diferencias en las variables clave de las empresas vitivinícolas en vista de su consideración como una empresa familiar en España. Utilizando una base de datos de 520 bodegas con las principales variables utilizadas en la literatura, este trabajo analiza las diferencias entre ser una bodega familiar o no familiar sobre el desempeño, el tamaño y la estructura de la deuda. Las empresas fueron clasificadas como familiares o no familiares, para posteriormente realizar un test de medias para todas las variables clave entre ambos grupos. Este estudio sugiere que existen diferencias significativas entre las empresas familiares y las no familiares en la rentabilidad económica (ROA) y en el margen de beneficios, que son mayores en el caso de empresas clasificadas como empresas familiares y en la relación de deuda y deuda relativa, los cuales son más altas en compañías consideradas no familiares. Las variables restantes son estadísticamente iguales. Los mejores márgenes en las empresas familiares podrían deberse a las ventajas en los precios derivados de los productos o marcas ofrecidas o a los menores costes de agencia que pueden conducir a una mejora en los costes de gestión, lo que explica tales diferencias. Además, la menor exposición al riesgo que llevaría a las empresas familiares a optar por fórmulas de apalancamiento menos riesgosas que conducirían a un aumento de la financiación a largo plazo podría explicar por qué estas ventajas no se reflejan en la rentabilidad financiera (ROE).

Both wine and gastronomy are considered as standard bearers of the cultural identity of a region (López-Guzmán, Di-Clemente, & Hernández-Mogollón, 2014). The great tradition of Mediterranean countries in grape cultivation and wine production (Kamsu-Foguem & Flammang, 2014) has led to Spain being the largest wine producer in the world, in addition to one of the five most important tourist destinations (Gómez, Lopez, & Molina, 2015). This fact places the country as one of the best positioned to take advantage of, as indicated by Garibaldi, Stone, Wolf, and Pozzi (2017), the strategic component representing wine tourism within experiential tourism, as reflected in the study on a Spanish tourist region with a great wine tradition such as Jerez and the region's Sherry carried out by López-Guzmán, Vieira-Rodríguez, and Rodríguez-García (2014). However, over the last few decades the competition has been increased by the entry of new wine producers, both at the domestic and at the international level (Agostino & Trivieri, 2014), which has led to a chronic excess of production estimated at more than 30 million hectolitres with significant environmental consequences (Chiusano, Cerutti, Cravero, Bruun, & Gerbi, 2015).

Some researchers have analysed the impact of different formulas of management on the sector, as is the case of Coren and Clamp (2014) who investigated wine distribution cooperatives in Wisconsin. In this context, some researchers, such as Lombardi, Dal Bianco, Freda, Caracciolo, and Cembalo (2016), found that Spanish wine producers are especially prone to increasing export volumes, to the detriment of the price. This export initiative is due, among other reasons, to the drop in consumption in the domestic markets of traditionally producing countries such as Spain (Castillo & García, 2013). The research of Lombardi et al. (2016) also positions Italy in the same direction as Spain. However, in the case of the Italian wine industry, the concept of sustainability has been taken seriously (Schimmenti, Migliore, Di Franco, & Borsellino, 2016). To better understand the concept of sustainable wine, it is recommended to go to the review carried out by Schäufele and Hamm (2017) or Sellers's (2016) research focused on the Spanish consumer. The results of the study of Gabzdylova, Raffensperger, and Castka (2009) on the New Zealand wine industry suggested that one of the greatest triggers for the introduction of sustainable environmental practices is satisfaction with the profession. This level of involvement has usually been attributed to family businesses and their members (Donckels, 1991; Dunn, 1996). Likewise, family firms maintain a strong emphasis on the concept of corporate social responsibility (Dyer & Whetten, 2006) even in times of crisis, which has repercussions on higher returns to non-family businesses (Kashmiri & Mahajan, 2014). Moreover, due their long-term orientation (Dyer, 2003; Lumpkin, Brigham, & Moss, 2010; Zellweger, 2007), they have a great capacity to generate patient capital (Arregle, Hitt, Sirmon, & Very, 2007). This difference in performance between family and non-family businesses has been contrasted in many articles in many sectors, although with disparate results among those in which there was a negative relationship between family influence and performance (e.g. Cronqvist & Nilsson, 2003) and those where such a relationship was positive (e.g. Anderson & Reeb, 2003; Craig, Dibrell, & Garrett, 2014; Massis, Kotlar, Campopiano, & Cassia, 2013; Miralles-Marcelo, Miralles-Quirós, & Lisboa, 2015; Sraer & Thesmar, 2007). Some postulate that such differences in performance are related to the generation of the family that manages the company (Arosa, Iturralde, & Maseda, 2010), while others point to the selected performance measures (e.g. Sacristán-Navarro, 2011).

Nevertheless, research on family businesses in the wine sector is practically non-existent. Some studies have analysed specific aspects of the family wine sector outside Spain, such as the research of Gallucci, Santulli, and Calabrò (2015) in Italy, Pavel's (2013) research in Lodi, California or the research of Woodfield and Husted (2017), who focused on the transfer of knowledge in family enterprises in New Zealand. While that is true, in Spain, as far as we know, the only existing research was the one developed by Lombardo, Ortiz, and Martos (2008), whose results suggested that the growth of family businesses in the sector tends more towards family reasons than towards business reasons. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to analyse the fundamental differences in the key values of wine companies based on their consideration as a family business in Spain. This work will establish a starting point for further work within this important sector for Spain.

The literature has revealed a very large group of differences between family and non-family businesses (Gomez-Mejia, Berrone, & De Castro, 2011). But first, we need to ask, what is understood as a family business? There is certainly no consensus in the literature about what a family business is and is not (Astrachan & Shanker, 2003). There is more than one way to define what we mean by family business (Agyapong & Boamah, 2013) and, due this fact, the literature has produced diverse and sometimes disparate results (Cano-Rubio, Fuentes-Lombardo, & Vallejo-Martos, 2017). As a result, the diversity of theories and perspectives represented in this developing field draw a disorderly and conflictive scenario (Schulze & Gedajlovic, 2010) in what is recognised as one of the main problems of the topic (Astrachan, Klein, & Smyrnios, 2002). The fundamental difference lies in the three keystones of a family business, i.e. property, the possibility of a family to influence management and succession (Miralles-Marcelo et al., 2015). This definition varies according to where the researcher or researchers place the focus of their research (Soler & Gémar, 2016).

Increasingly, in family business research (Utrilla, Torraleja, & Vázquez, 2012), one of these more widespread focuses is to take advantage of the particular proximity between the ownership and management of family businesses, which assumes a reduction of agency costs versus corporate governance where the separation between ownership and management is clear (Yoshikawa & Rasheed, 2010), to employ agency theory and agency costs. In addition, this approach takes into account that families linked to businesses lose or earn more than money. There is a socio-emotional component of the relationship with the company that needs to be preserved (Gómez-Mejía, Haynes, Núñez-Nickel, Jacobson, & Moyano-Fuentes, 2007), which leads family businesses, according to the model of behavioural risk-taking agency developed by Wiseman and Gomez-Mejia (1998), to be more risk averse when emotional wealth is threatened. As a result, family businesses diversify less than non-family ones and, when they do, they prefer domestic rather than international diversification, and, in the case of the latter, they choose regions that are culturally close (Gomez-Mejia, Mejia, Makri, & Kintana, 2010).

Agency costs are not eliminated in the family business and some types of costs may increase as the level of ownership control increases (e.g. Schulze, Lubatkin, & Dino, 2003a; Schulze, Lubatkin, Dino, & Buchholtz, 2001). This is because the introduction of the emotional component and interfamiliar conflicts can raise the agency costs to the point of requiring external intermediation (Corten, Steijvers, & Lybaert, 2017; Michel & Kammerlander, 2015). In fact, some authors argue that agency costs in family businesses may be higher than among the non-family business (e.g. Gomez-Mejia, Nunez-Nickel, & Gutierrez, 2001).

Using agency theory, some researchers have succeeded in separating the effects of the family on ownership and influence on management (e.g. Block, Jaskiewicz, & Miller, 2011), demonstrating that both are very different and finding a superior performance in the case of family property, while the results in the case of family management were more ambiguous. With respect to family property, and again employing agency theory, De Massis et al. (2013) found a U-shaped relationship between the degree of dispersion of family property and the performance of the firm. In contrast, the results of Sciascia and Mazzola (2008) focus on family involvement in management to explain the negative quadratic relationship they found between management and performance. The same relationships were found by Minichilli, Corbetta, and MacMillan (2010), who, making use of agency theory, reach the conclusion that while the presence of a family CEO is beneficial to the company's performance, the coexistence of groups or factions among family and non-family administrators within the top management team has the potential to create schisms between subgroups. Other authors, like Acquaah (2011), put the emphasis on the family's capacity to influence management. This paper, however, intends to put an end to the aforementioned disparity by opting for an objective classification criterion. Thereby, this work has taken the criterion of definition and classification of a family business established by Rojo Ramírez, Diéguez Soto, and López Delgado (2011), considering it the most objective and replicable of the existing ones.

Material and methodsThe data were extracted using as the source the Iberian Balance Sheet Analysis System [Sistema de Análisis de Balances Ibéricos (SABI)]. In order to discriminate the companies in the sector of interest, the identification code provided in the National Classification of Economic Activities of Spain [Clasificación Nacional de Actividades Económicas (CNAE)] for winemakers was used, gathering the latest information available in the second half of 2017 for Spanish companies in this group. In total, for the subsequent analysis, we were able to collect a sample of 520 wine cellars from a total population of 1389 wineries. We collected the main variables used in the literature to analyse the performance, size and structure of debt. With regard to the first set, data were collected on the return on assets (ROA) and the return on equity (ROE) (e.g. Kowalewski, Talavera, & Stetsyuk, 2010; Minichilli et al., 2010). In this sense, another series of variables was collected, which comprises the key components of these returns, such as the operating revenues, profit for the year and profit before tax, in order to delve into the nature of possible differences. As regards the second set of variables, this consists of the size of the company measured by the number of employees (e.g. Deephouse & Jaskiewicz, 2013; Gomez-Mejia et al., 2010; Ilias, 2006) and the total amount of assets (e.g. Corten et al., 2017), which is the same thing as measuring the composition of debt and equity of the company (e.g. Anderson, Mansi, & Reeb, 2003). The collection of these components also allowed us to extract information for the third set of variables, which was intended to evaluate possible differences between family companies in the financing methods, while serving to delve into possible differences in the performance measures listed first. This last set of variables includes owner's equity and current and non-current liability. It was also interesting to explore if there were differences in the way of operating through the analysis of working capital. Moreover, in order to analyse relative measures of debt composition, different ratios such as relative debt and debt ratio were included. These are relative measures that, like ROA and ROE, facilitate comparison between firms under conditions of heterogeneity, a tremendously important aspect in family business research (e.g. Burkart, Panunzi, & Shleifer, 2003; Chrisman, Chua, Kellermanns, & Chang, 2007; Chua, Chrisman, & Rau, 2012; Corten et al., 2017; De Massis et al., 2013; Gomez-Mejia et al., 2001; Schulze et al., 2001; Schulze et al., 2003a).

In order to classify the companies as family or non-family business, we applied the criterion of Rojo Ramírez et al. (2011). The criterion, which is in line with the type of information and the source of the analysis data, uses SABI and an objective flow diagram to classify the companies as family or non-family businesses. This criterion has been used in recent research, such as that of Soler and Gémar (2016), among others, to eliminate heterogeneity in the definition of a family business. As a result, the companies were classified as a family or non-family business using a dichotomous variable that took the value 0 in the case of a non-family business and 1 in the case of a family business. Then, a means test was performed for all key variables between both groups. Given the size of the sample, the normality of all variables was assumed, restricting the test of means to parametric methods. To determine the type of statistic test to be applied and given that the population variances are unknown, it is first necessary to know if it is possible to assume the equality of variances between groups, which was verified by the well-known Levene's test (1960). Then, with the information on the equality of the variances of both groups, the correct test was applied.

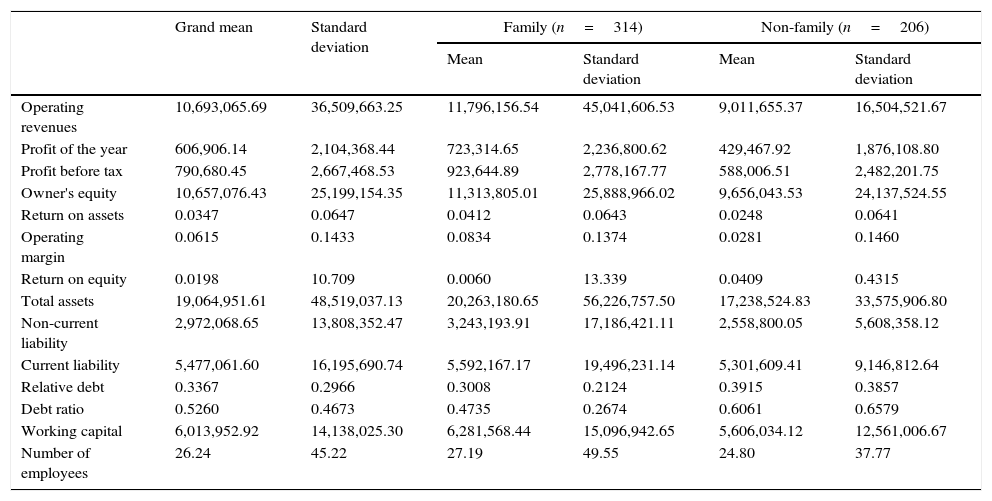

ResultsTable 1 shows the descriptive variables of study, mean and standard deviation, both globally and disaggregated for family and non-family businesses.

Descriptive values.

| Grand mean | Standard deviation | Family (n=314) | Non-family (n=206) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard deviation | Mean | Standard deviation | |||

| Operating revenues | 10,693,065.69 | 36,509,663.25 | 11,796,156.54 | 45,041,606.53 | 9,011,655.37 | 16,504,521.67 |

| Profit of the year | 606,906.14 | 2,104,368.44 | 723,314.65 | 2,236,800.62 | 429,467.92 | 1,876,108.80 |

| Profit before tax | 790,680.45 | 2,667,468.53 | 923,644.89 | 2,778,167.77 | 588,006.51 | 2,482,201.75 |

| Owner's equity | 10,657,076.43 | 25,199,154.35 | 11,313,805.01 | 25,888,966.02 | 9,656,043.53 | 24,137,524.55 |

| Return on assets | 0.0347 | 0.0647 | 0.0412 | 0.0643 | 0.0248 | 0.0641 |

| Operating margin | 0.0615 | 0.1433 | 0.0834 | 0.1374 | 0.0281 | 0.1460 |

| Return on equity | 0.0198 | 10.709 | 0.0060 | 13.339 | 0.0409 | 0.4315 |

| Total assets | 19,064,951.61 | 48,519,037.13 | 20,263,180.65 | 56,226,757.50 | 17,238,524.83 | 33,575,906.80 |

| Non-current liability | 2,972,068.65 | 13,808,352.47 | 3,243,193.91 | 17,186,421.11 | 2,558,800.05 | 5,608,358.12 |

| Current liability | 5,477,061.60 | 16,195,690.74 | 5,592,167.17 | 19,496,231.14 | 5,301,609.41 | 9,146,812.64 |

| Relative debt | 0.3367 | 0.2966 | 0.3008 | 0.2124 | 0.3915 | 0.3857 |

| Debt ratio | 0.5260 | 0.4673 | 0.4735 | 0.2674 | 0.6061 | 0.6579 |

| Working capital | 6,013,952.92 | 14,138,025.30 | 6,281,568.44 | 15,096,942.65 | 5,606,034.12 | 12,561,006.67 |

| Number of employees | 26.24 | 45.22 | 27.19 | 49.55 | 24.80 | 37.77 |

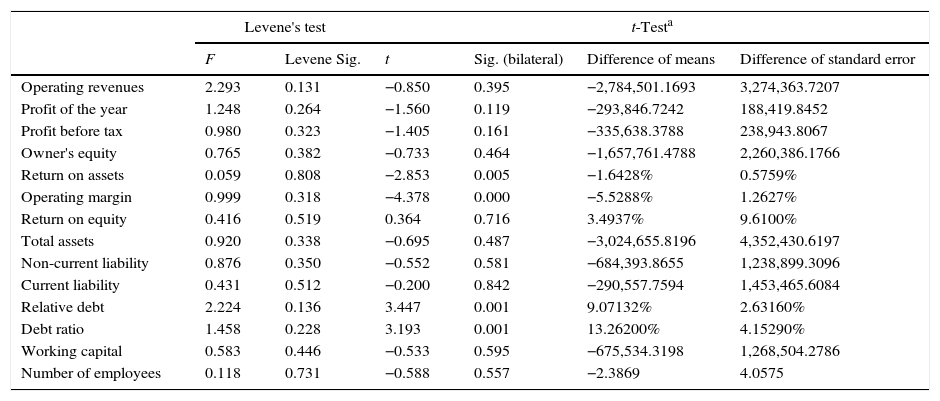

In Table 2, the results of the Levene's test and the test of means are collected. Since there is no attribute for which the Levene's test is significant, the alternative hypothesis must be discarded and all variances are equal. In this context, the statistic for the test of means is t, being in all cases the degrees of freedom of 518.

Variances and means test results.

| Levene's test | t-Testa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Levene Sig. | t | Sig. (bilateral) | Difference of means | Difference of standard error | |

| Operating revenues | 2.293 | 0.131 | −0.850 | 0.395 | −2,784,501.1693 | 3,274,363.7207 |

| Profit of the year | 1.248 | 0.264 | −1.560 | 0.119 | −293,846.7242 | 188,419.8452 |

| Profit before tax | 0.980 | 0.323 | −1.405 | 0.161 | −335,638.3788 | 238,943.8067 |

| Owner's equity | 0.765 | 0.382 | −0.733 | 0.464 | −1,657,761.4788 | 2,260,386.1766 |

| Return on assets | 0.059 | 0.808 | −2.853 | 0.005 | −1.6428% | 0.5759% |

| Operating margin | 0.999 | 0.318 | −4.378 | 0.000 | −5.5288% | 1.2627% |

| Return on equity | 0.416 | 0.519 | 0.364 | 0.716 | 3.4937% | 9.6100% |

| Total assets | 0.920 | 0.338 | −0.695 | 0.487 | −3,024,655.8196 | 4,352,430.6197 |

| Non-current liability | 0.876 | 0.350 | −0.552 | 0.581 | −684,393.8655 | 1,238,899.3096 |

| Current liability | 0.431 | 0.512 | −0.200 | 0.842 | −290,557.7594 | 1,453,465.6084 |

| Relative debt | 2.224 | 0.136 | 3.447 | 0.001 | 9.07132% | 2.63160% |

| Debt ratio | 1.458 | 0.228 | 3.193 | 0.001 | 13.26200% | 4.15290% |

| Working capital | 0.583 | 0.446 | −0.533 | 0.595 | −675,534.3198 | 1,268,504.2786 |

| Number of employees | 0.118 | 0.731 | −0.588 | 0.557 | −2.3869 | 4.0575 |

The results show that there are significant differences between family and non-family businesses in the ROA and in the operating margin, which are both superior in the case of companies classified as family businesses and in the relative debt and debt ratio, which were higher in companies considered as non-family businesses. Being the remaining variables statistically equal. Particularly relevant is the non-significance of the ROE, given its relationship with the ROA and the company's debt, both of which are significant.

DiscussionThe results suggest that family companies in the wine sector are economically more profitable than non-family businesses. Since neither the operating revenues nor the profit before and after tax differ, this improvement in profitability must come from a greater efficiency of the family business, as suggested by the work of Agyapong and Boamah (2013). As Pavel (2013) proposed, in this sector a family dynasty can maintain key competencies that favour the family companies against those that are not. Furthermore, it may also be due to evidence on the positive influence of family culture on improving the strategic flexibility of the company, which benefits both innovation and performance (Craig et al., 2014), an effect that can be reduced if several generations are involved in the top management of the company (Kraiczy, Hack, & Kellermanns, 2014).

This efficiency would be reflected in the differences in the profit margin as shown by the results. These differences are in line with the literature and could be the result of higher prices, which, as Carney's (2005) results demonstrate, would be due to the preference of these companies for higher-quality products or services. Moreover, it could be due to the better acceptance of the brands of the family companies given their ability to acquire a better reputation and differentiation than non-family companies (e.g. Carrigan & Buckley, 2008; Orth & Green, 2009; Zellweger, Eddleston, & Kellermanns, 2010; among others). They could also be the result of cost improvements in family businesses. However, although there is evidence in the literature in this regard (e.g. Cruz, Gomez-Mejia, & Becerra, 2010; Fama & Jensen, 1983), family firms possess advantages in brand-building as well as a propensity for higher-quality products, as mentioned above. Further, the findings in the literature on the good treatment that family firms tend to give their employees (e.g. Barontini & Caprio, 2006; Bertrand & Schoar, 2006; Erbetta, Menozzi, Corbetta, & Fraquelli, 2013; Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2005; among others) suggest the more likely option of the price path. This would be in line with the complexity of the wine sector, which is characterised by great complexity, non-linearity and a lack of objective information about the quality of the desired final product (Gómez-Meire, Campos, Falqué, Díaz, & Fdez-Riverola, 2014). Related to this is the customers’ tendency towards heuristic decision processes related to brand components (Ketron, Spears, & Dai, 2016), which have fostered new forms of marketing (Festa, Cuomo, Metallo, & Festa, 2016) that seem to favour companies with strong brands and clear quality signals. Supporting this would be the research carried out by Gallucci et al. (2015), who found that Italian family wine companies that combined family involvement in management with brand strategies that communicate the family (e.g., family history, values and identity) as a corporate brand show higher rates of sales growth. This fact seems to be supported by the results, which discard improvements resulting from economies of scale. Neither the volume of assets nor the number of employees differ significantly between family and non-family businesses. In addition, the lower turnover associated with a range of premium-type products would be in line with the equal benefits shown by the results for family and non-family businesses.

However, this difference is not repeated with the ROE. A meta-analysis carried out by Boyle, Pollack, and Rutherford (2012) could point in this direction; it found no significant relationship between family involvement and a firm's financial performance. Everything seems to indicate that the management of the leverage and the interest rates within the family businesses of the sector do that such a difference in the return on equity does not exist. This fact would be in line with the results, which show significant differences in the two variables of evaluation of the leverage and with the generalised vision of a greater risk aversion by the family companies found in the literature (e.g. Craig & Moores, 2006; Dyer, 2006; Schulze, Lubatkin, & Dino, 2003b). This could be aligned with a small business orientation and its influence on higher performance in family businesses (Madison, Runyan, & Swinney, 2014). Inasmuch as the results show equality in the structure of the liability – i.e. on the current and non-current liability and on the owner's equity – in lines with Guerrero and Barrios's (2013) results as well as equality in total assets and working capital, the difference between the two groups should come, as mentioned above, by the better margins in family companies and not by a smaller proportion of current assets. This rules out a better management of stock that would imply better levels in the component of the rotation. However, such equality in the structure of the liability is eliminated by calculating the differences on the relative variables of indebtedness that eliminate the heterogeneity in the structure and size of the companies; for this reason, family companies tend to have lower debt rates than those that are considered to be non-family. This lower exposure to risk would lead to family companies betting on less risky leverage formulas that would lead to greater long-term financing and could therefore have associated higher financial costs. Financial cost could explain why the advantage obtained by family companies in economic management is lost in the financial management. This imposition of the cost of risk aversion would tax the benefit of the shareholder (Shleifer & Vishny, 1986). As a result, it is possible to say that the owners of a family business could benefit from a riskier financial policy. However, this fact, although it can improve the return on equity, can also compromise the survival of family firms and goes against the long-term view generally found in the literature (e.g. Dyer, 2003; Lumpkin et al., 2010; Zellweger, 2007).

ConclusionThis work proves the existence of differences in some key variables such as the ROA between family and non-family businesses, although it does not delve into the causes. In alignment with Mazzi's (2011) arguments, this paper argues that the relationship between a family business and performance is a highly complex issue that needs further research. However, it aims to serve as a turning point in the investigation of the Spanish family wine sector. In the absence of research, it is unknown if the difference in this ROA responds more to better management of the brand by the family companies or better products that have more-competitive prices and therefore better margins or, as suggested by Pavel (2013), to an advantage in costs resulting from the managerial abilities transmissible in a family business. It is also possible that, in this case, lower agency costs may lead to an improvement in management costs, thereby accounting for such differences. In this line would be found a great body of literature, as for example in the research of Fama and Jensen (1983) or more recently in the research carried out by Cruz et al. (2010). However, specific research is needed in the sector in order to check whether this is true for the wine sector.

Nor is the reason for an equivalence in the ROE despite the differences found in either the debt ratios or the ROA. Spanish wine companies may be paying a cost for a less risky strategy, which would cause the advantages obtained in the margin to be offset by the cost of such a risk aversion. Such an outcome could be in line with the behavioural agency model of executive risk taking developed by Wiseman and Gomez-Mejia (1998). This must be demonstrated in the sector in future research, as it is also possible that this is due to the strong pressure for the payment of dividends that can be exercised by family owners (Anderson & Reeb, 2003; Carney & Gedajlovic, 2002). Notwithstanding the foregoing, such conclusions could contradict what was pointed out by the results of the research of Anderson et al. (2003), wherein the founding family ownership was related to a lower cost of debt financing in the large listed companies as a result of lower agency costs. Such results may be due to the fact that these listed companies may have independent directors that act as a balance on family board representation. This was what emerged from the research of Anderson and Reeb (2004), which, in consonance with agency theory, found such companies to be the most valued. Yoshikawa and Rasheed (2010) showed that in listed companies, family control was linked to higher dividend payments while foreign ownership interacted with family control to reduce dividend payments and increase profitability. This behaviour in listed companies may not represent the generalisability of the sector, especially taking into account the importance of heterogeneity in the family business mentioned above and as declared by Sciascia and Mazzola (2008). The disparity of results is especially relevant in unlisted companies. For this reason, this paper suggests that the knowledge of the functioning of the wine sector and family businesses could be advanced through the application in the research of models based on agency theory and in stewardship theory, in line with what was suggested by Schulze and Gedajlovic (2010). The differences between the two, as argued by Breton-Miller, Miller, and Lester (2011), lie in the fact that while agency theory holds that the principal owners of the company, acting in the interest of the family, will sub-invest in the company, avoid risks and extract resources, stewardship theory argues that both owners and managers will act prudently and will invest generously to improve the business value.

With regard to future lines of research in addition to the above, this paper considers and encourages other researchers to address the possible relationship between family businesses and more sustainable and eco-friendly wine production, as has been verified in other investigations (e.g. Berrone, Cruz, Gomez-Mejia, & Larraza-Kintana, 2010; Craig & Dibrell, 2006; Sharma & Sharma, 2011). It is also believed that it would be worth investigating whether there are differences in the customers’ search for information and risk, depending on whether the brand belongs to a family or non-family wine company. This would be in line with the research of Atkin and Thach (2012), who found significant differences both in the search for information and in the perceived risk between different generational cohorts for the wine sector. Also, having these results would be interesting for future investigations to determine if there is a greater propensity to pay for wines created by family companies. This could be done by using the Heckit model, as in the work of Sellers-Rubio and Nicolau-Gonzalbez (2016), to analyse the case of sustainable wine or using the known hedonic price method, which offers a precedent for the analysis of the influence of a family business on prices, such as the hotel case developed by Soler and Gémar (2016).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.