Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) is under-investigated in First Episode Psychosis (FEP). BPD psychotic manifestations and mood changes are also difficult to differentiate from first episode affective psychosis. The aim of this study was to compare sociodemographic and clinical features between FEP patients with BPD vs. Bipolar Disorder (BD) or Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) both at baseline and across a 2-year follow-up period.

Methods224 FEP participants (49 with BPD, 93 with BD and 82 with MDD) completed the Health of the Nation Outcome Scale (HoNOS), the Positive And Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) and the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale. Psychiatric diagnosis was reformulated at the end of our follow-up. Inter-group comparisons were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis or the Chi-square test. A mixed-design ANOVA model was also performed to assess the temporal stability of clinical scores within and between the 3 subgroups.

ResultsCompared to FEP/BD subjects at baseline, FEP/BPD patients showed higher depressive symptom severity and lower excitement severity. Compared to FEP/MDD at entry, they had a higher prevalence rate of substance abuse, a lower interpersonal impairment and a shorter DUP. Finally, they had a lower treatment response on HoNOS “Psychiatric Symptoms” subscale scores across the follow-up in comparison with both FEP/BD and FEP/MDD individuals.

ConclusionBPD as categorical entity represents a FEP subgroup with specific clinical features and treatment response. Appropriate treatment guidelines for this FEP subgroup are thus needed.

Although the term “borderline state” historically characterized individuals experiencing both psychotic and neurotic features,1 psychotic symptoms in current diagnostic criteria for Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) are listed only in the form of stress-related, transient paranoid ideation and/or dissociative symptoms.2 However, it was reported that their clinical presentation in BPD are more heterogeneous than what modern classification systems suggest.3 In this respect, empirical studies observed that the most common psychotic features in BPD are auditory verbal hallucinations (often experienced as controlling, distressing and critical)4 and persecutory delusions (frequently disconnected from shared reality and persisting over time in the absence of ongoing stress).5

Psychotic symptoms in BPD are also often considered as clinical indicators of illness severity and poor prognosis. They are associated with high levels of psychopathology, more co-occurring mental disorders (such as mood disorder and substance use disorder) and high rates of new hospitalization and suicidal behavior.6 It is therefore crucial to detect psychotic features in BDP as soon as possible, especially at clinical onset of the personality disorder, in order to prevent the development of a severe mental illness in the future.7

Psychotic symptoms may also occur in the first clinical presentation of mood disorders. In this respect, empirical evidence showed that earlier age at onset in affective disorders is associated with higher rates of psychotic symptoms.8 Specifically, while depressive onset is often related to suicidality, manic onset is often associated with delusions.9 Moreover, mixed states in patients with bipolar disorder are frequently associated with younger age of onset and the presence of psychotic features.10

As adolescence and young adulthood are two crucial sensitive life periods in which psychotic symptoms, mood disorder and BPD psychopathology frequently emerge for the first time,11 research interest on BPD and affective disorders has recently focused on young individuals with First Episode Psychosis (FEP). However, evidence on BPD prevalence and its associations with psychotic features and mood alterations in FEP patients is still poor.12 This is also because in early psychosis, it is difficult to distinguish whether psychotic symptoms are inherent to BPD or primary psychotic disorder,13 as well as whether early mood swings/changes are related to BPD or primary mood disorder.14 Differential diagnosis among these conditions is of great relevance in clinical practice, especially for providing specific effective interventions and for an appropriate decision making process.

Starting from this background, the aims of this retrospective study were:

- (1)

to compare clinical, sociodemographic and treatment characteristics at baseline between FEP patients with a final diagnosis of BPD or affective psychosis (i.e., bipolar or major depressive disorder), all specifically recruited and treated for FEP within a specialized “Early Intervention in Psychosis” (EIP) service;

- (2)

to examine inter-group comparisons in the longitudinal course of clinical and outcome parameters (i.e., drop-out rate, new hospitalizations, new suicide attempt/self-harm behavior) across a 2-year follow-up period.

To our knowledge, no research specifically comparing BPD and affective psychosis in FEP populations has been published in the literature to date.

Material and methodsParticipantsAll participants were FEP patients recruited within the “Parma Early Psychosis” (Pr-EP) program between January 2013 and December 2021. This EIP protocol was developed not as a specialized “stand-alone” service, but as a “diffuse” infrastructure that was implemented in all adolescent and adult mental health services of the Parma Department of Mental Health (in the Northern Italy).15

Inclusion criteria for this research were: (1) to be specialist help-seeker; (2) age 12-35 years; (3) to be enrolled for FEP in the Pr-EP program; (4) presence of BPD or affective (bipolar or major depressive) psychosis as final psychiatric diagnosis according to the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria;2 and (4) “Duration of Untreated Psychosis” (DUP) of < 2 years. This DUP was selected because it is the usual time limit to offer effective evidence-based interventions within the EIP paradigm.16 For the specific purposes of this investigation, FEP patients enrolled in the Pr-EP program with a final diagnosis outside BDP or affective psychoses (n = 197) were excluded, but they will be considered for future comparative papers.

Exclusion criteria were: (1) past psychotic episode within DSM-5 diagnosis of both affective and non-affective psychosis; (2) past exposure to antipsychotic medication or current antipsychotic intake for more than 2 months prior to the Pr-EP enrollment; (3) neurological disorder or any other medical condition presenting with psychiatric symptoms; and (4) known intellectual disability (i.e., intelligence quotient < 70). We considered past exposure to antipsychotic drug (i.e., in previous illness episodes and independently from psychotic symptoms) as “functional equivalent” of past psychotic disorder. Indeed, this is in accordance with the psychosis threshold definition proposed by Yung and co-workers17 in the original EIP paradigm (i.e., “...essentially that at which antipsychotic therapy would probably be started in common clinical practice”). A current antipsychotic intake for less than 2 months was also selected because it is the time range specifically defined for completing the assessment phase within the Pr-EP protocol.18

All individuals and their parents (if minors) gave their written informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study. Local ethical approval was obtained for the research (AVEN protocol n. 36102/09.09.2019). This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

AssessmentIn this investigation, the clinical evaluation included the “Positive And Negative Syndrome Scale” (PANSS),19 the “Global Assessment of Functioning” (GAF) scale2 and the “Health of the Nation Outcome Scale”.20 These instruments were completed at baseline and every 12 months during the follow-up period by trained Pr-EP team members. Regular scoring workshops and supervision sessions ensured a good inter-rater reliability.21

The PANSS is a clinical interview specifically assessing psychotic psychopathology, also in the early phases of psychosis.22 As proposed by Shafer and Dazzi,23 we considered 5 main psychopathological dimensions: “Negative Symptoms”, “Affect” (“Depression/Anxiety”), “Positive Symptoms” “Disorganization” and “Excitement”. The Italian version of the PANSS24 has been commonly used in young Italian people with FEP.25

The GAF is a widely used scale assessing daily functioning in individuals with psychosis. The Italian version of the GAF has been frequently used also in young Italian individuals with FEP.26

The HoNOS was developed to assess social and clinical outcomes in people with severe mental illness. As proposed by Gale and Boland,27 we considered 4 main outcome domains: “Psychiatric Symptoms”, “Impairment”, “Social Problems” and “Behavioral Problems”. The Italian version of the HoNOS28 has been frequently used also in young Italian patients with FEP.29

Finally, a sociodemographic and clinical chart (also collecting information on DUP and past self-harm/suicidal behaviors) was completed at baseline.30 The DUP was defined as the time interval (in months) between the onset of full-blown psychotic symptoms and the first pharmacological treatment.31 The term “suicide attempt” was defined as a potentially injurious, self-inflicted behavior without fatal outcome, for which there was an implicit or explicit intent to die.32 It was differentiated from deliberate self-harm acts or intoxication with alcohol/drugs without evidence of intent to die, which were classified as “self-harm” behaviors.33

ProceduresThe FEP diagnosis was formulated at baseline in accordance with the CAARMS (“Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States”)17 criteria for psychosis threshold. Patients fulfilled CAARMS clinical high risk criteria were excluded from this research. The primary psychiatric diagnosis was defined by at least two trained Pr-EP team members according to the DSM-5 criteria using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 disorders (SCID-5)34 and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 personality disorders (SCID-5-PD).35 Specifically, it was formulated both at baseline (“provisional” diagnosis) and after 2 years of follow-up (“final” diagnosis). For participants who did not complete the 2-year follow-up period (see Supplementary Materials [Table S1] for details), the final diagnosis was defined together with clinicians treating and managing FEP participants. Individuals with BPD as final diagnosis were included in the FEP/BPD subgroup. Patients with affective (bipolar or major depressive) disorder as final diagnosis were grouped in the FEP/BD or FEP/MDD subgroup.

Based on symptom severity, FEP participants were provided with a 2-year comprehensive treatment protocol including psychopharmacological therapy and a multicomponent psychosocial intervention (combining psychoeducational sessions for family members, intensive case management and individual psychotherapy [oriented on cognitive-behavioral principles]), as suggested by current EIP guidelines on the topic.36 Low-dose atypical antipsychotic medication was used as first-line pharmacological therapy.37 Mood stabilizer, serotonin selective reuptake inhibitor and/or benzodiazepine could also be used to treat mood changes, anxiety and insomnia.38

As for inter-group comparisons, sociodemographic and clinical features were examined at baseline and every 12 months across the 2-year follow-up period. We also compared the 3 subgroups on four main outcome indicators across the follow-up (i.e., drop-out rate, new hospitalization, new suicide attempt and new self-harm behavior).

Statistical analysisData were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) for Windows, version 15.0.39 All tests were two-tailed with a significance level set at 0.05. In inter-group comparisons, continuous parameters were examined using the Kruskal-Wallis H and the Mann-Whitney U tests. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square test. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis to compare outcome indicators among the subgroups was also performed. This allowed us to consider the different time duration of individual follow-ups and participants who dropped-out before the conclusion of our research.40 Finally, a mixed-design ANOVA model (with post-hoc Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons) was performed to assess the temporal stability of PANSS, GAF and HoNOS scores within and among the subgroups across the follow-up.41

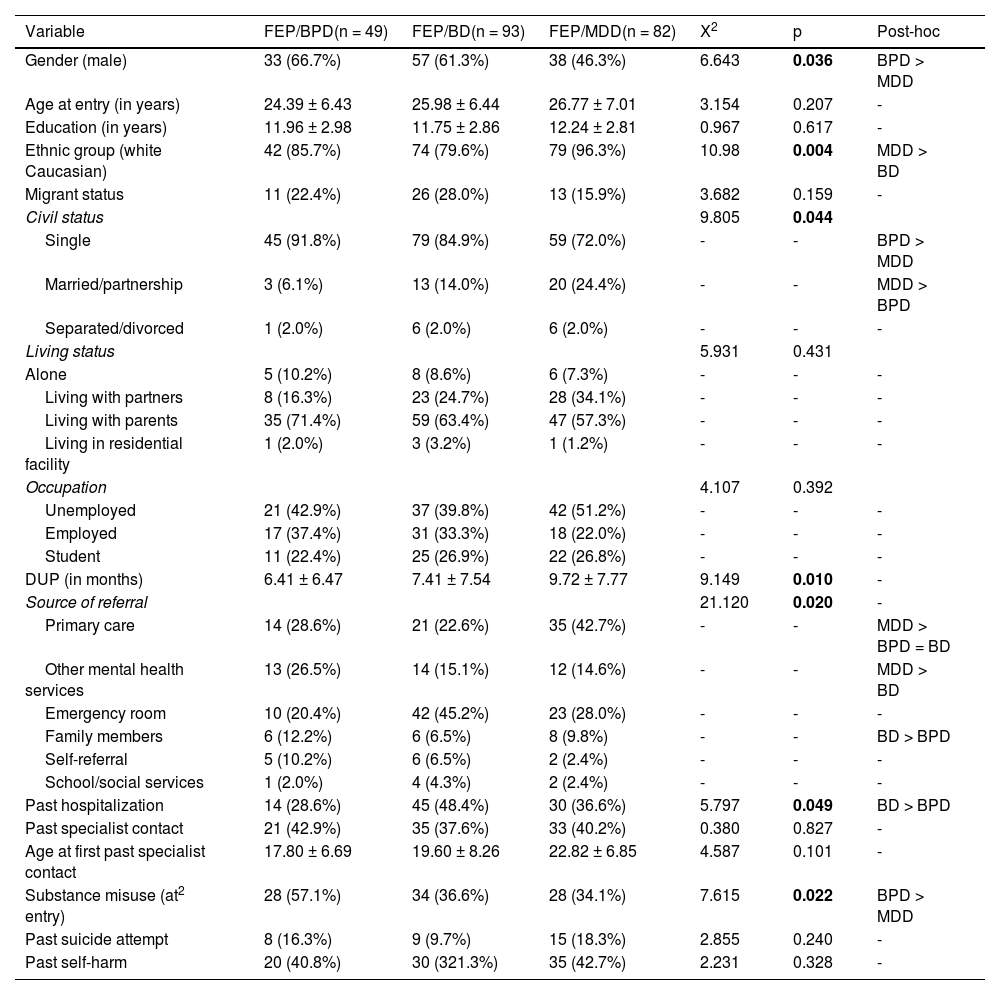

ResultsForty-nine FEP individuals had BPD as final diagnosis and were included in the FEP/BPD subgroup. The remaining participants were included in the FEP/BD (n = 93) or FEP/MDD (n = 82) subgroups (for diagnosis at baseline, see Supplementary Materials [Table S2]). Specifically, FEP/BPD participants were mainly recruited in the Pr-EP program with a baseline primary diagnosis of schizophreniform disorder (n = 13; 26.5%), substance-induced psychotic disorder (n = 13; 26.5%), psychotic disorder not otherwise specified (n = 11; 22.4%) and brief psychotic disorder (n = 10; 20.4%). Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the three subgroups are shown in the Table 1.

Baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the 3 FEP subgroups (n = 224).

Note. BPD = Borderline Personality Disorder; FEP = First Episode Psychosis; BD = Bipolar Disorder; MDD = Major Depressive Disorder; DUP = Duration of Untreated Psychosis. Frequencies (percentages), mean ± standard deviation, Chi-squared test (Χ2) and Kruskal-Wallis H test (X2) values are reported. Post-hoc test results is also reported. Statistically significant p values are in bold.

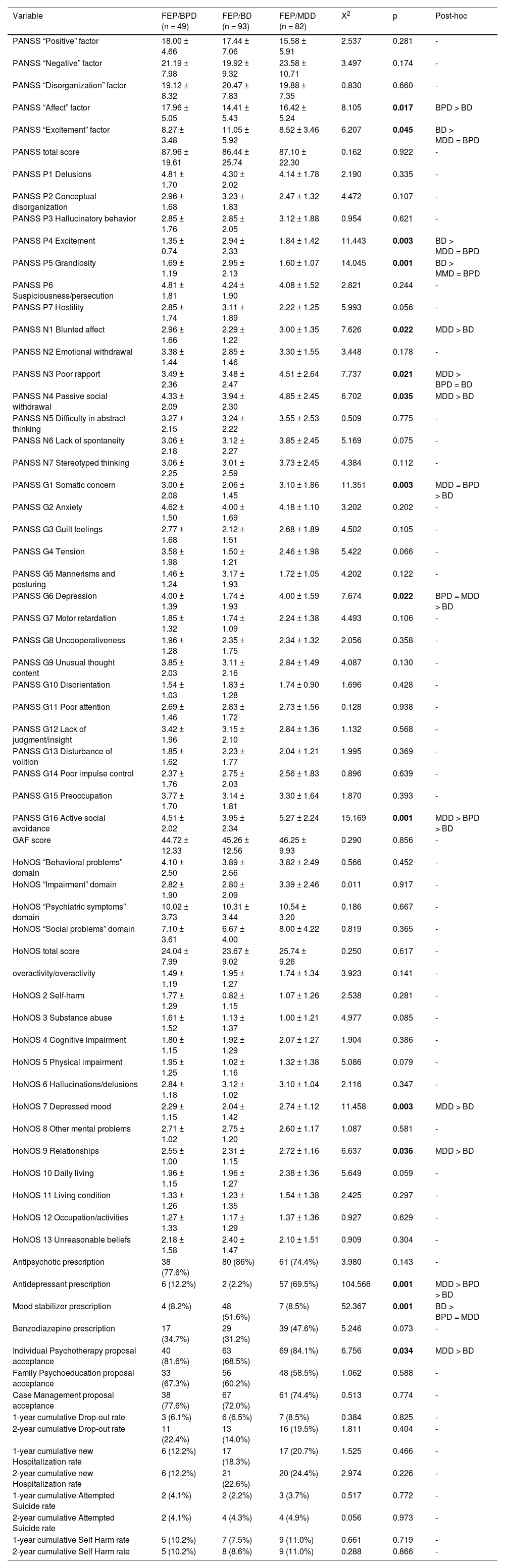

Compared to FEP/BD, FEP/BPD participants showed a greater percentage of past hospitalization and a higher rate of emergency room as primary source of referral to the Pr-EP program (Table 1). They also had a higher PANSS “Affect” factor score (especially higher PANSS “Depression”, “Somatic Concern” and “Active Social Avoidance” item subscores) and a lower PANSS “Excitement” factor score (especially lower PANSS “Excitement” and “Grandiosity” item subscores). Finally, they showed a higher rate of antidepressant prescription and a lower rate of mood stabilizer prescription at entry (Table 2).

Baseline psychopathological and Pr-EP treatment characteristics of the 3 FEP subgroups (n = 224).

Note. BPD = Borderline Personality Disorder; FEP = First Episode Psychosis; BD = Bipolar Disorder; MDD = Major Depressive Disorder; Pr-EP = Parma Early Psychosis program; PANSS = Positive And Negative Syndrome Scale; GAF = Global Assessment of Functioning; HoNOS = Health of the Nation Outcome Scale. Frequencies (percentages), mean ± standard deviation, Chi-squared test (Χ2) and Kruskal-Wallis H test (X2) values are reported. Post-hoc test results are also reported. Statistically significant p values are in bold.

In comparison with FEP/MDD, FEP/BPD individuals were more frequently singles and had a shorter DUP and a higher percentage of males and a higher rate of substance misuse at presentation (Table 1). Moreover, they showed a lower rate of antidepressant prescription and a lower PANSS “Poor Rapport” and “Active Social Avoidance” item subscores (Table 2).

Longitudinal resultsOne hundred and thirteen participants (50.4% of the FEP total sample) concluded the 2-year follow-up period (see Supplementary Materials [Table S1] for details). Among subjects who did not complete the follow-up, 40 dropped out the Pr-EP program (16 of them before the 1-year assessment time) and 71 were disengaged in accordance with the treatment staff (44 for clinical improvement and 27 because moving outside the catchment area and they could not be contacted for follow-up assessments). No statistically significant inter-group differences in outcome parameters were found (see Supplementary Materials [Tables S2-S6] for details)

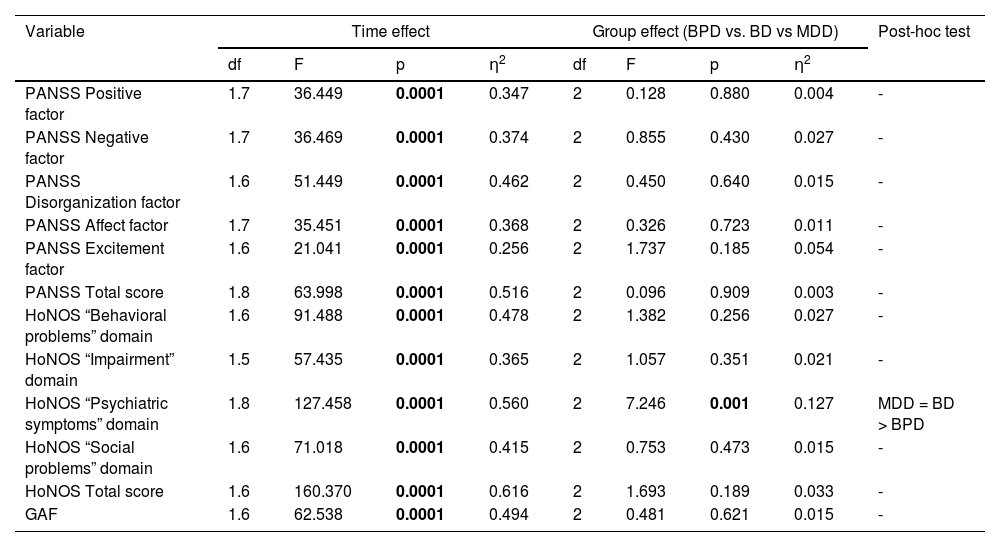

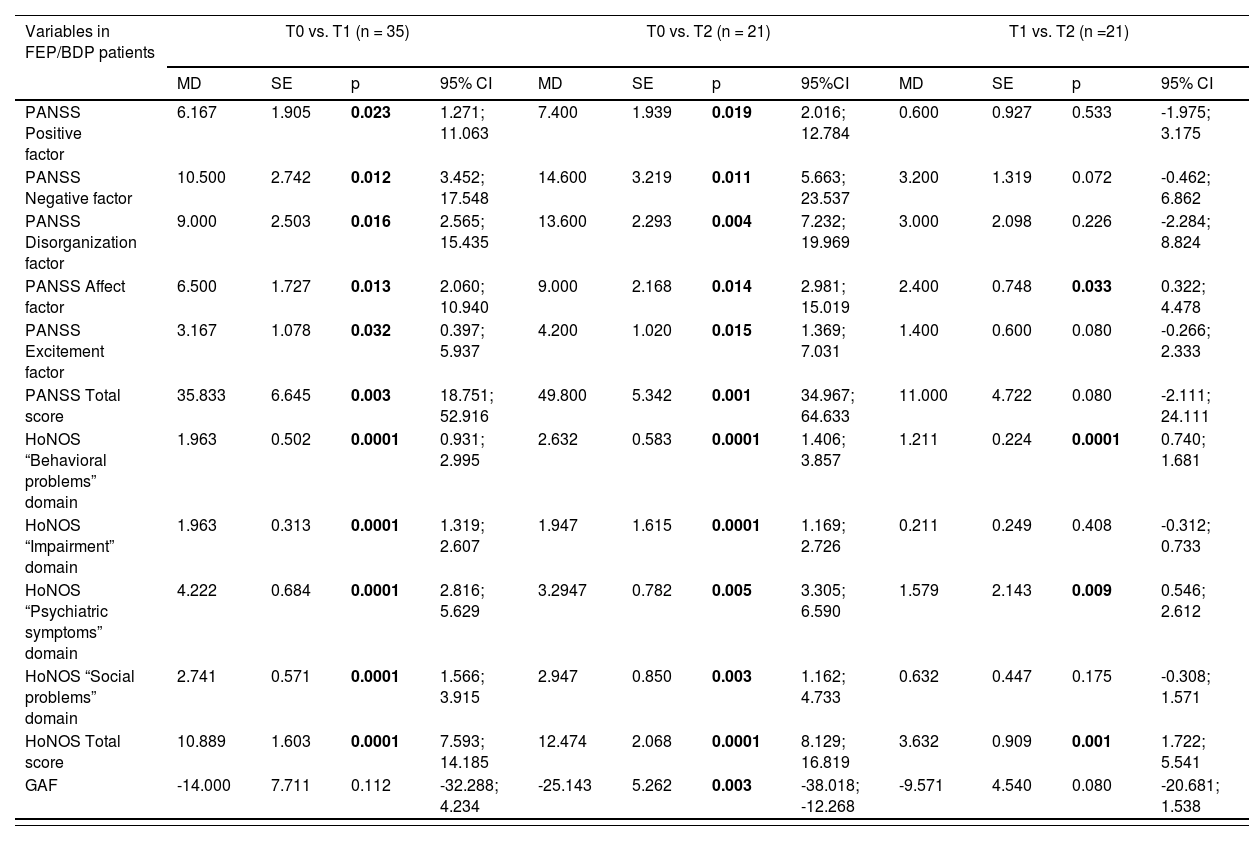

Mixed-design ANOVA results on repeated measures (i.e., “within-subject” effect) showed a significant effect of time on all HoNOS, PANSS and GAF scores (Table 3). Notably, a statistically significant group effect was observed: i.e., both FEP/MDD and FEP/BD participants showed higher improvements in HoNOS “Psychiatric Symptoms” domain subscores across the 2-year follow-up period in comparison with FEP/BPD subgroup (Table 4).

Mixed-design ANOVA results: psychopathological and outcome characteristics across the 2-year follow-up period in the FEP total sample (n = 224).

Note. As all Mauchly's tests of sphericity are statistically significant (p<0.05), Greenhouse–Geisser corrected degrees of freedom to assess the significance of the corresponding F value are used. Statistically significant p values are in bold. ANOVA = analysis of variance; BPD = Borderline Personality Disorder; BD = Bipolar Disorders; MDD = Major Depressive Disorder; PANSS = Positive And Negative Syndrome Scale; GAF = Global Assessment of Functioning; HoNOS = Health of the Nation Outcome Scale; df = degrees of freedom; F = F statistic value; p = statistical significance; η2 = partial eta square.

Post-hoc test on psychopathological and outcome characteristics across the 2-year follow-up period among the 3 FEP subgroups.

Note. FEP = First Episode Psychosis; BDP = Borderline Personality Disorder; BD = Bipolar Disorder; MDD = Major Depressive Disorder; PANSS = Positive And Negative Syndrome Scale; HoNOS = Health of the Nation Outcome Scale; GAF = Global Assessment of Functioning; MD = Mean difference; SE = Standard Error; T0 = baseline assessment; T1 = 1-year assessment time; T2 = 2-year assessment time; p = statistical significance; 95% CI = 95% Confidence Intervals. Statistically significance p values are in bold.

The results of this study showed that FEP/BPD subjects at baseline had specific sociodemographic and clinical features in comparison with FEP/MDD and FEP/BD patients. Specifically, compared to BD presenting as FEP, they had less access to the hospital (i.e., a lower rate of past hospitalization and a lower percentage of emergency room as primary source of referral), lower excitement levels and higher severity levels in anxious-depressive symptoms. This could have contributed to their higher rate of antidepressant prescription and their lower rate of mood stabilizer prescription at entry.

In line with our findings, a recent systematic review on clinical features at BD presentation showed that depressive symptoms have an earlier onset in BPD than in BD, and that BD patients have more frequently mixed or manic symptoms.42 According to Paris,43 the BPD onset is more commonly accompanied by transient and less severe mood shifts (especially as depressive polarity), whereas BD is associated with sustained mood changes. Although BD and BPD share overlapping phenomenology and are frequently misdiagnosed,44 their distinction is of clinical relevance because misdiagnosis may deprive patients of potentially effective treatment (already at the onset of their psychopathological trajectories), whether it is psychotherapy for BPD or medication for BD.45

Compared to MDD presenting as FEP, our FEP/BPD participants showed no significant baseline differences in depressive symptoms and severity levels of both general and psychotic psychopathology (despite having a lower rate of antidepressant prescription). At entry, they were more likely to be male and single, and showed a shorter DUP, a higher rate of substance misuse and a higher interpersonal functioning.

Although not specifically recruiting subjects with first-episode affective psychosis as comparison group, the “Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre” (EPPIC) cohort differently showed that FEP patients with co-occurring borderline personality psychopathology at entry were more likely to be younger and female compared to individuals with FEP alone.46 In line with our findings, they had a higher baseline prevalence of current substance abuse.47 In this sense, substance misuse may be considered as a specific behavioral problem that more frequently characterize the onset of FEP with comorbid BPD diagnosis rather than first-episode depression with psychotic features. In our BPD individuals, it could also induce a shorter DUP, due to the problematic nature of pathological addiction behavior and/or its related help-seeking request.48 However, the DUP decrease in FEP/BPD patients may also be associated with their higher social/interpersonal ability and their more effective help-seeking behavior,49,50 as suggested by their lower baseline PANSS “Poor Rapport” and “Active Social Avoidance” item subscores compared to FEP/MDD patients.

In this investigation, mixed-design ANOVA results showed a statistically significant effect of time on all psychopathological and clinical parameters in the three FEP subgroups. However, across the follow-up, a statistically relevant group effect was found on HoNOS “Psychiatric Symptoms” domain scores in FEP/BPD patients compared to both FEP/MDD and FEP/BD participants. This suggests lower beneficial effects of specialized Pr-EP interventions on BPD psychopathology and a need to differentiate EIP protocols according to categorical diagnosis, as well as to implement adapted and non-stigmatizing care for FEP individuals with BPD comorbidity. In this respect, a pilot study on young patients with FEP and BPD showed the feasibility and efficacy of a hybrid psychosocial program combining elements of early intervention for BPD within specialized FEP interventions.51

LimitationsA first methodological limitation was the relatively small sample sizes of our 3 subgroups. This could explain the lack of statistically relevant inter-group differences in outcome parameters. Therefore, future studies on larger FEP populations meeting BPD diagnostic criteria and/or with first episode affective psychosis are needed.

Second, we specifically examined FEP individuals in a “real-world” clinical setting primarily aimed at providing specialized EIP interventions within community mental healthcare services. Thus, our results should be compared only to similar clinical populations.

Another important limitation was related to the diagnostic assessment procedure. In this research, the DSM-5 diagnoses were formulated both at baseline and after the 2-year follow-up period, and only individuals with BPD as final diagnosis were included in the FEP/BPD subgroup. Thus, our findings should be compared exclusively to similar FEP/BPD populations. Indeed, comparison difficulties could arise using different assessment strategies to categorize FEP subjects with BPD (such as the BPD screening instrument, which does not use a structured clinical interview method to differentiate the categorical disorder from its subthreshold features).

Fourth, another concern included the use of BPD instead of “Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder” or personality disorder traits in adolescence. Indeed, some authors suggested that BPD in adolescents (especially under the age of 25) can be a harmful, invalid construct that is unnecessary for effective treatments and evaluation of alternatives.52 However, in this investigation, no BPD participants was under the age of 16 at baseline and her/his primary diagnosis was generally reformulated after two years of follow-up.

An additional weakness was related to the use of the SCID-5 and the SCID-5-PD in adolescents (instead of other widely used instruments, such ad the “Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrtenia” [K-SADS]).53 However, the SCID-5 and the SCID-5-PD are the most used diagnostic clinical interviews in mixed adolescent and young adult FEP populations, especially in order to make the diagnostic process more homogeneous and coherent.

Furthermore, the current study was designed within a specialized EIP program not specifically focused on BPD in FEP. Indeed, BPD psychopathology was not longitudinally assessed. Therefore, future prospective studies exploring BPD symptoms with more specific assessment instruments (such as the “BPD Checklist”)54 are needed. This is of primary importance, since investigations exploring BPD in FEP samples are still relatively scarce and the presence of psychotic symptoms in BPD patients is a well-known clinical indicator of illness severity and poor prognosis.

Finally, we did not assess the presence of autism spectrum disorders, which are frequently documented in some of these young people, especially in child and adolescent mental health services.

ConclusionsPsychotic symptoms may characterize individuals with BPD as categorical disorder at the presentation within EIP services. The results of this investigation suggest that BPD represents a FEP subgroup with specific clinical and sociodemographic features that are helpful in differentiating it from first episode affective psychosis. In particular, this FEP subgroup is usually recruited within specialized EIP services for having initial unstable and/or undefined psychotic diagnoses (such as schizophreniform disorder, psychotic disorder not otherwise specified or brief psychotic disorder) or for a substance-induced psychotic disorder. Therefore, it is crucial to explore and detect the underlying BPD condition in the clinical practice, especially for providing more specific and appropriate therapeutic interventions.

In this respect, compared to FEP/BD at entry, our FEP/BPD showed lower excitement, more severe depressive symptoms and a lower rate of hospital admission. In comparison with FEP/MDD, they showed a higher rate of current substance misuse, la ower interpersonal impairment and a shorter DUP.

Finally, traditional EIP interventions seem to be less effective in FEP/BPD individuals compared to first episode affective psychosis. Therefore, future investigation establishing appropriate treatment guidelines for this complex patient group (such as the “Good Psychiatric Management”)55 is needed.

Ethical considerationsAll individuals and their parents (if minors) gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study. The approval of the institutional review board (IRB) was obtained for the research (AVEN protocol n. 36102/09.09.2019). This study was conducted in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for experiments involving humans.

FundingThis research received no specific grant from any funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. The “Parma Early Psychosis” (Pr-EP) program was partly financed through a special, treatment-oriented regional fund: “Progetto Esordi Psicotici della Regione Emilia Romagna”.

For their facilitating technical and administrative support in the Pr-EP program, the authors gratefully acknowledge the “Early Psychosis Facilitators Group” members (Sabrina Adorni, Andrea Affaticati, Anahi Alzapiedi, Paolo Ampollini, Patrizia Caramanico, Maria Teresa Gaggiotti, Tiziana Guglielmetti, Mauro Mozzani, Matteo Rossi, Lucilla Maglio, Matteo Tonna, Fabio Vanni and Matteo Zito) and the “Quality Staff Group” members (Patrizia Ceroni, Stefano Giovanelli, Leonardo Tadonio) of the Parma Department of Mental Health and Pathological Addictions. The authors also wish to thank all the patients and family members who actively participated to the Pr-EP program.