This systematic review aimed to investigate the experiences and opinions of people with mental illness regarding the role of telemedicine in their treatment.

MethodsTo be eligible, studies were required to include people between 18 and 65 years of age with mental illness, defined as depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or personality disorder. It was further required that the patients’ experiences of the telehealth solutions were reported. Between April 5, 2020, and June 29, 2020 (renewed November 10, 2021), the CINAHL electronic database was searched. Using the OVID search engine, Embase, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO were likewise searched; gray literature was retrieved from Scopus. The included studies were critically appraised using the CASP checklists.

ResultsSeventeen studies were included. Treatment provided via telehealth technology offered people with mental illness insights and skills that helped them cope better in everyday life. The patient—therapist relationship was improved where the parties collaborated. Furthermore, gaining control of one's mental health by using an app and following one's development empowered people with mental illness, leading to greater involvement in treatment.

ConclusionsEngaging people with mental illness in decisions concerning the use of telehealth technology is essential. It is likewise important that both people with mental illness and health professionals have access to help with the implementation of technology, and that telehealth solutions function as a supplement rather than a substitute for face-to-face treatment.

All over the world, the burden of mental illness is growing, with substantial impact on health and human rights, and major social and economic consequences for the individual and for society.1 Severe mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, anxiety, and depression, are often associated with disability and barriers to treatment.2 Besides problems with accessing mental healthcare, social isolation and stigma are among the several challenges facing people with severe mental illness.3,4 To address those barriers, the use of various telehealth technologies, such as email, online programs, and mobile applications (henceforth apps), has increased rapidly.5 The potential of telehealth for the treatment of people with severe mental illness is demonstrated by positive results regarding medication adherence, symptom severity, cognitive therapy, and hospitalisation length.6–8 Interventions involving telehealth are numerous and include telephone calling, email correspondence, apps with music or mindfulness exercises, access to symptom records, cognitive therapy programs, and help with structuring daily life and tasks.9 Most studies of telehealth practices in mental healthcare have included the use of online devices such as private mobile phones or tablets.8,10 The market potential of telemedicine has shown to be strong, and the implementation is expected to grow the next years.11 To make a successful implementation, it is crucial that patients find the telehealth solution useful and feel involved in the use of it; thus their experience of the use of telehealth in their everyday life and treatment is important.12 Although several reviews have explored the effectiveness, costs, and quality of telehealth interventions, frequently reporting positive results,2,3,5 this review is, to our knowledge, the first to give an overview of the experiences of people with severe mental illness where telehealth is involved. Our aim was therefore to investigate the opinions and experiences of people with mental illness regarding the role of telemedicine in their treatment and give some insight to consider when new telehealth solutions are developed.

Material and methodsThe protocol was registered in PROSPERO (ID: CRD42020183000) and due to Covid-19 automatically published exactly as submitted. Findings are reported under the PRISMA Group's Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis guidelines.13 The protocol's stated aim was to investigate the experiences and opinions of people with mental illness and healthcare professionals regarding the role of telemedicine. However, we chose to concentrate on the patients’ perspectives in order to achieve focused and unambiguous results.

Eligibility criteriaTo ensure a focused search process, several inclusion criteria were applied. We searched for studies of any design including reports of mentally ill patients’ perspectives on the use of telemedicine in the treatment of their mental illness. The studies were required to include patients diagnosed with mental illness, defined as depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or personality disorder, aged between 18 and 65 years, corresponding to the age span applied in adult psychiatry in Denmark. Only if data were stratified by age did we consider including studies of patients below or above those ages.

Information sources and search strategyThe search strategy was developed using the Population, Exposure, Outcome (PEO) framework and customized for the searched databases and their structures.14,15 Search terms were divided into three categories: mental illness (population), telehealth (exposure), and user involvement (in treatment) (outcome). The complete search string is shown in the Appendix.

An information specialist was consulted regarding search terms, keywords, and the choice of databases. Between April 5, 2020, and June 29, 2020, the CINAHL electronic database was searched. Using the OVID search engine, Embase, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO were likewise searched; gray literature was retrieved from Scopus. Depending on the database in question, Synonyms, MESH terms, and Thesaurus were customized for each category and combined with the Boolean operator OR. The categories were subsequently combined using AND. The search was renewed in November 2021.

Study selectionThe search results were uploaded and stored using Endnote version 9.3, duplicates were removed and the results subsequently imported to the Covidence reference programme (www.covidence.org), where two authors (SJ and BN) independently screened the studies for inclusion. Studies were excluded due to wrong study design (i.e., protocols or opinion papers without data), population, outcomes, or language. Any disagreement among the reviewers concerning the eligibility of studies was resolved by discussion. Studies meeting the inclusion criteria were retrieved for full text analysis.

Data collection process and data itemsData extraction was conducted in a two-stage process. Two independent reviewers (SJ and BN) extracted the following study characteristics: bibliographic information, location, study aim, study design, data collection method, type of intervention, type of e-health technology, inclusion and exclusion criteria, time and place of data collection, sampling strategy, participants’ characteristics, and data analysis techniques. Afterwards, results sections and Discussion sections of the included studies were scrutinised to identify their themes. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Quality assessmentThe included studies were appraised independently by two reviewers (SJ and BN), using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist (2019).16

To ensure a rigorous and fair assessment, we considered all italicised prompts listed under each question in the checklist, giving particular emphasis to Question 1 (“Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research?”) to ensure that the aim of the study was in line whit our review, and Question 4 (“Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research?”) which became important because of the number of nested study we included, and finally Question 5 (“Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue?”) which was particularly relevant because we wanted to investigate mental ill patients’ experiences with telehealth and thus, a qualitative approach was preferred. In the scoring, 1 point was allocated for Yes, 0.5 points for Can't tell (unsure) and 0 points for No. Disagreements occurred only concerning unclear criteria fulfilment; consensus was reached by discussion.

Data synthesis and interpretationThe study data were extracted electronically and entered into NVivo. To ensure consistent methodology, data extraction was performed by a primary reviewer (SJ) and confirmed by a secondary reviewer (BN).

We employed an inductive approach in which the themes were synthesised from the primary data during discussions among the authors.17 In the first, purely descriptive stage of the three-stage thematic analysis, we formulated a set of codes17 that adhered to the studies’ own formulations. In the second stage, we identified and described themes across the developed codes.17 In Stage 3, analytical themes were generated and their relevance for the review question was considered.

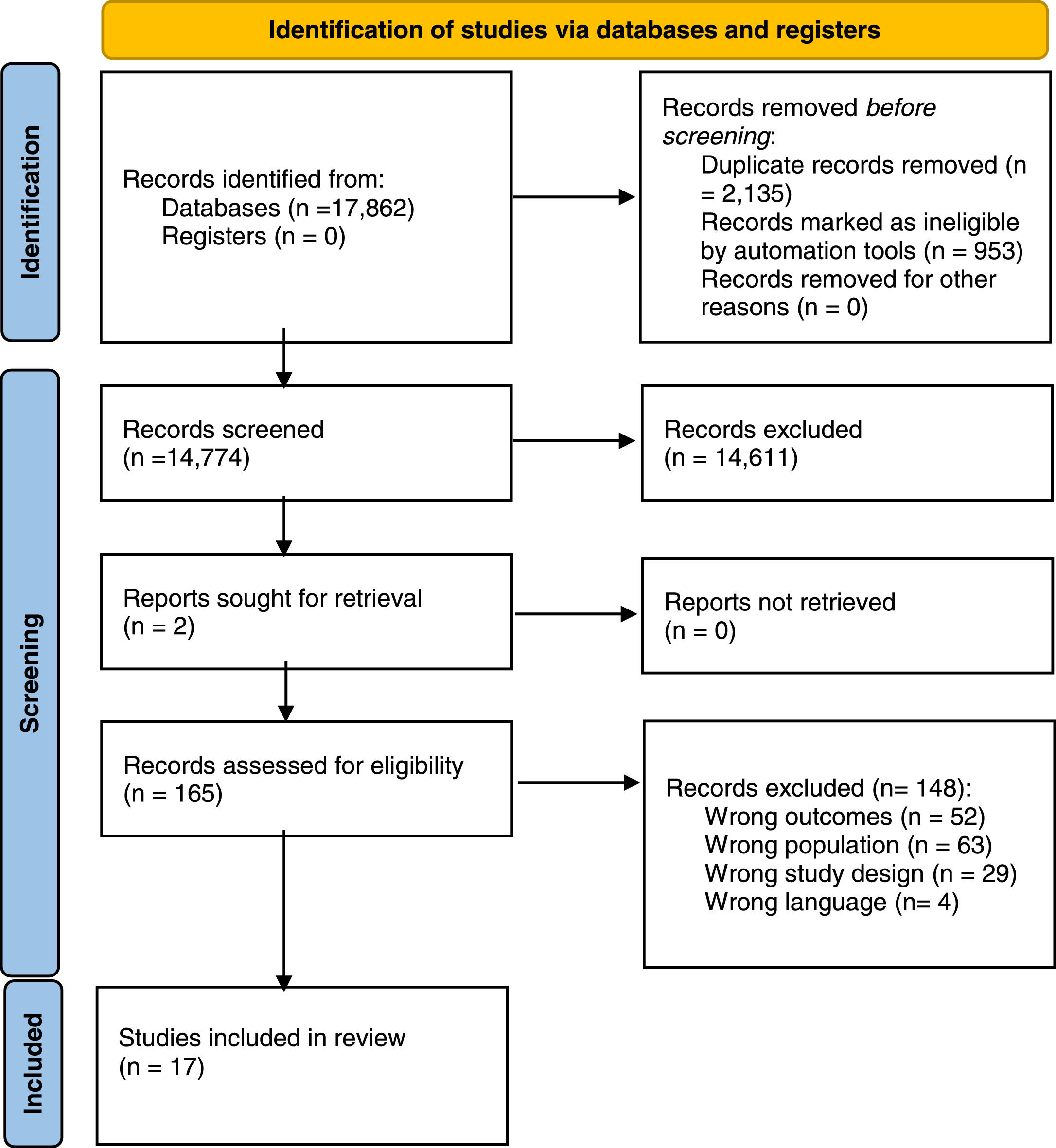

ResultsStudy selectionThe database search identified 17,862 titles. Following the exclusion of 3088 duplicates, 14,774 articles were screened based on their titles and abstracts. Of these, 14, 609 studies were deemed irrelevant, leaving 165 studies for full-text reading. The inclusion criteria were met by 17 studies. Figure 1 gives further details.

PRISMA flow diagram.11

Of the 17 studies included, four originated in the United Kingdom,18–21 four in Denmark,22–25 two in the United States,26,27 two in Netherlands,28,29 two in Norway,30,31 one in Australia,32 one in Germany,33 and one in Sweden,34 respectively. All studies collected data through qualitative individual interviews. The 281 participants were aged between 18 and 65 years; 117 identified as males, 134 as female; the sex of 30 interviewees was undisclosed.

Most of the studies were thematically structured, using methods that included theoretical template coding, phenomenological analysis, framework analysis, and constructivist grounded theory method.

The telehealth practices applied in the studied programs varied substantially. In two studies the MoodGYM self-help program30,31 was used to explore the patient's experience of guided internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy with therapist support; one study reported the use of video sessions delivering cognitive processing therapy via Skype technology.18 Four studies involved apps as an alternative to paper-based records of mood, behavior, sleep patterns, and other parameters as needed21,22,25,28 and one study compared experiences with the FOCUS and WRAP apps, representing individual and group session therapy, respectively.26 To explore the value of e-health in a newly transformed mental healthcare setting, Lorenz-Artz et al.29 investigated the users’ experiences of using several e-health tools. Asking the patients to choose a self-care app, Crosby and Bonnington19 investigated the motivations for their choice. Using the Momentum app, Korsbek and Tønder23 explored the patient's experience of the app as a consultation tool. Five studies used apps24,27,32–34 or web-based programs offering behavioral activation programs and various therapy sessions. Finally, a study used short messages (SMS) or apps to investigate the patients’ experience of undergoing clinical assessment for psychosis.20

Further details of the study characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Study characteristics.

The CASP scores for the studies varied between 7 and 10, indicating a range from low quality (below 7.5) to moderate (7.5—9.0) or high quality (9.0—10.0).35 Negative ratings were typically ascribed to failure to report on the participant—researcher relationship or ethical issues. Details of the quality assessment are presented in Table 2.

Quality assessment.

Twenty-eight codes emerged in Stage 1. Reorganization in Stage 2 reduced the number to five descriptive themes, four of which became analytical themes with identical wordings in Stage 3. The remaining codes were combined into the analytical theme named Therapy on the users’ terms. A code concerning personal safety was excluded as it had no clear association with the review question.

The resulting five analytical themes were: Use of telehealth technology, Therapy on the users’ terms, The approach – the stance toward the apps, collaboration, and Motivation.

Use of telehealth technologyThis analytical theme appeared across all of the studies and was constituted by the following seven codes: Use of telehealth, Support base, Disturbances, Deficiencies, Technical skills, Travel time and Transport.

Exploring the influence of restrictions on or long waiting times for face-to-face consultations, the studies found that users were more inclined to accept telehealth treatment in such situations. It appeared that the use of technology improved compliance by helping the users structure their daily life through reminders to follow the programs at a particular time. Using a smartphone facilitated completing and evaluating tasks compared to writing by hand. Users were less prone to make excuses as the technology appeared to make them feel obliged to comply with their program, although some were challenged to find peace and space for treatment at home. They cited disruptions such as a ringing doorbell, the return of a family member, or finding the designated therapy space occupied. Some users seemed to be motivated to use the apps because they saw this as a way to avoid disturbing the therapist. Numerous users found the apps and websites’ ways of using psychoeducation helpful for them to understand their mental illness, and even better if they had an option afterward to discuss it with their therapist. It was generally emphasized that the app had to be user-friendly for the users to continue using it. Many users appreciated the availability of technical support for the setup and stressed the importance of a modular setup enabling the selection of tasks according to the needs of the moment. One study showed that the users appreciated the saving of time and expenses for transport. Several studies found that users value the opportunity to show information about their illness and treatment progress to their relatives. The majority of users indicated that telehealth should be used as a supplement rather than a substitute for face-to-face treatment and that it should be considered whether the treatment provided by the telemedicine solution was suited to the individual.

Therapy on the users’ termsThis analytical theme emerged from the following five codes: Therapy on the users’ terms, Therapy access time, Discreet, Being on one's own, and Focus on therapy.

Overall, the studies found that telehealth worked well from the users’ perspective. Their reasons for the positive assessments included for example adaptability and flexibility and freedom to interrupt treatment for toilet breaks. The apps were considered safe spaces with a soothing effect. In one of the studies, it was shown that receiving therapy in the home helped users stay focused as they saved resources for leaving the house and worrying about the trip to the treatment site. The flexibility offered by online treatment enabled users to pursue their everyday routines. Many appreciated the flexibility, with access to therapy at all times of the day or when most urgent, rather than having to wait for a scheduled treatment session. For some users, it had proved difficult to cope with the abrupt transition from an online session to everyday life, while many embraced the opportunity for social networking and feedback offered by some of the online therapies. Some studies showed that the users could experience a lack of support from a therapist when using telehealth solutions, which made them feel more alone or isolated. The apps had given many participants a sense of independence, needing less help from others. The ubiquity of mobile telephones meant that users could access treatment discreetly, even in public spaces.

Stance toward the appsAppearing across all the included studies, this analytical theme was mainly formed by five codes: The stance toward the apps, Managing symptoms, Combining functions, Buy-and-throw-away, and A supplement to therapy. Diversion was a minor theme.

The user's attitude to the use of the apps hinged on their previous experiences; if they had experienced that apps previously were convenient, empowering, and immediately useful, users would feel positive about using it. They enjoyed the easy accessibility of the phone, which provided constant access to treatment. Apps for anxiety and depression treatment were seen as particularly useful tools. The degree to which an app was used was affected by the participant's present state of mind; when they were well, the app would be used less frequently, also how much support they were offered from their therapist to adopt the app. Some users found that when their mood was low, they were unable to cope with the demands the apps placed on them. A study found that although users no longer access a specific app, many did not remove it from their device but kept it in case of relapse. Some users worried that they would be stigmatized if other people should see the app logo on their mobile screen and take this as an indication of mental illness. For most users, the app offered an “instant fix”. The telehealth treatment provided insight and skills to cope with difficulties and helped users adopt new coping strategies and identify triggers in their everyday life. The possibility of entering and monitoring their symptoms in a software program enabled the user to realize the progression in their recovery. Some users saw this facility as an improvement in taking paper notes, as it helped them make detailed and discreet notes on the spot. The users tended to find it easy to install and uninstall apps that they had selected themselves. Overall, it was found that users expected the apps to offer instantaneous help.

CollaborationThe collaboration theme was based on eight codes, including collaboration, Experience from previous therapy, Impersonal, It's the same thing, Familiar, Communication, Shared perspectives, and Togetherness.

While some studies showed that apps made users withdraw from face-to-face treatments, others showed that several users had experienced that accessing the programs together with their therapist helped them maintain the essence of their treatment. Many reported that using an app in collaboration with the therapist had a positive impact on their relationship and collaboration. When the collaboration included an app, the users felt more in control as this allowed them to prepare for the consultation. Some studies showed that apps could have the effect of the user withdrawing from treatment elements involving face-to-face contact. The users experienced having more control when apps were integrated. In general, collaboration with the therapist was perceived as essential to the success of treatment, as this helped the users understand some of the difficult information given in the programs or apps. Some of the studies showed that many users felt a need to know the therapist in advance to be motivated for treatment. Meeting the same therapist throughout the treatment was essential to providing users with a sense of familiarity. While the users reported no major difference in their experience of face-to-face therapy and online therapy, they emphasized the importance of visual contact with their therapist. Being able to read their body language gave them a sense of a normal treatment session. Some users reported a lack of deeper emotions with the telehealth technology, compared to face-to-face sessions. However, there was substantial variation in the degree of satisfaction with the contact with the therapist afforded by the technology. While some patients had been quite satisfied, others had come to realize that they longed to return to conventional face-to-face therapy forms. Several studies found a strong correlation between user satisfaction and their sense of having the therapist's full attention. Group therapy was experienced as a positive element by some users, while others cited it as their reason for abandoning treatment. Among the advantages of apps, users mentioned the improved communication between clinicians and service users and the opportunity for the therapist to follow treatment progress by monitoring their use of the program.

MotivationThe motivation theme derived from a single code that appeared in all but one of the studies.

The users were empowered by the feeling of control over their mental health conferred by the apps. Being able to track their improvement led to stronger engagement in their treatment. The user's motivation to use a specific app and collaboration with their therapist was associated; a therapist who shared their reactions and communicated positively about the app reinforced the users’ motivation and commitment to treatment. As telehealth practices require more independence compared with face-to-face practices, users may have been more prone to postpone or cancel appointments with the therapist. Conversely, using an app could strengthen the sense of responsibility for improving their health. For some, the motivation declined as the treatment progressed, while for others it increased as they got a better grasp of the program.

DiscussionThe studies examined here have demonstrated that telehealth treatment provides users with insights and skills to cope with their difficulties and helps them acquire new coping strategies in their everyday life. Furthermore, we found that telehealth should supplement rather than substitute face-to-face treatment. The studies generally showed that collaboration in using apps has a positive impact on the patient-therapist relationship. Users feel in better control of their mental health and appreciate the opportunity to track improvements when apps form part of the collaboration, leading to greater involvement in their treatment. Moreover, the ubiquity of mobile telephones in public spaces allows them to access treatment discreetly.

Several of the included studies indicate that users see the flexibility of telehealth technology as a gain, for example the easy access to treatment and its round-the-clock availability. This corroborates the review of Wehman et al., which has shown that flexibility is an important cue for users to accept telehealth treatment despite the absence of face-to-face meetings.36

The reviewed studies also show that users appreciate having time to reflect on new information and being in control of telehealth sessions, the importance of which Richards et al. have already established.37 By findings by both Richards et al. and Lopez,37,38 we found that the inclusion of telehealth made users' experience of their treatment more accessible.

Wehmann et al. found no association between the use of telehealth technology and higher ratings of treatment effects, a result which is corroborated by our findings that users' experience treatment involving telehealth technology improves their connection with the health professional and strengthens their sense of being in control of their treatment. The included patients felt more connected to the health professionals when they experienced visual contact or at least had met the health professionals before interacting in the program.34

Comparing the experiences of introducing telehealth with and without an introduction to the interface, we show that when users feel listened to and guided in the use, their motivation to continue their telehealth treatment is reinforced, whereas they tend to discontinue their treatment when such help is absent. Apolinàrio-Hagen found significantly higher treatment completion rates when guidance was offered.39

Overall, this review supports the findings of previous studies that patients with mental illness generally experience telehealth practices as useful, provided they are offered as adjunctive to rather than the dominant medium of treatment.

This review was designed and reported following the recommendations of the PRISMA statement. A thorough search of multiple databases was conducted. Despite the rigorous search, screening, and analysis process, we acknowledge the existence of some limitations of this study. Our review was challenged by the COVID-19 pandemic in that the protocol was automatically submitted to the PROSPERO register and published without changes. We abandoned our initial aim to explore both patients’ and health professionals’ perspectives on telehealth when we realized that this was too broad an aim. This change of focus to the patient perspective was the sole deviation from the protocol.

It may have influenced our results that some of the studies included in this review were nested within randomized controlled trials. This is so mainly because our qualitative analyses are based on data that were not necessarily collected for purposes similar to ours. Another reason is that only five of the 17 studies described the researcher—participant relationship.

This review attempted to assure credibility in terms of internal validity by showing which codes were used to form the specific themes in the result section and by using two independent reviewers in the process, where disagreements were solved by discussion. Furthermore, the reviews’ dependability (or reliability) sought to be assured by providing a complete search string in the appendix and also which questions during a quality assessment, the reviewer chose to give particular interest.

The broad definition of telehealth applied in the studies presented another challenge, as our review covers a range of telehealth solutions, such as apps, video consultation, and computer-based group treatment. As we focused on the users’ experience of telehealth, we do not consider this a major limitation.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, our review has demonstrated the importance of including the patients in the decision to apply telehealth. If this approach is chosen, it is essential that both users and health professionals have access to help in implementing the telehealth solution, so patients feel confident using it. In addition, our review offers an overview of the current literature on the experiences of people with severe mental illness concerning telehealth practices.

Ethical considerationsThe authors declare that the review is conducted while paying attention to all perspectives of original studies and that they have conducted the review ethically. According to Danish law, no ethical approval is demanded for this type of research project.

FundingThis work was supported by Human Health, University of Southern Denmark and University College South Denmark.

Search in Cinahl

Search in Scopus

Search in MedLine, PsycInfo and Embase