Almost half of the individuals with a first-episode of psychosis who initially meet criteria for acute and transient psychotic disorder (ATPD) will have had a diagnostic revision during their follow-up, mostly toward schizophrenia. This study aimed to determine the proportion of diagnostic transitions to schizophrenia and other long-lasting non-affective psychoses in patients with first-episode ATPD, and to examine the validity of the existing predictors for diagnostic shift in this population.

MethodsWe designed a prospective two-year follow-up study for subjects with first-episode ATPD. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent variables associated with diagnostic transition to persistent non-affective psychoses. This prediction model was built by selecting variables on the basis of clinical knowledge.

ResultsSixty-eight patients with a first-episode ATPD completed the study and a diagnostic revision was necessary in 30 subjects at the end of follow-up, of whom 46.7% transited to long-lasting non-affective psychotic disorders. Poor premorbid adjustment and the presence of schizophreniform symptoms at onset of psychosis were the only variables independently significantly associated with diagnostic transition to persistent non-affective psychoses.

ConclusionOur findings would enable early identification of those inidividuals with ATPD at most risk for developing long-lasting non-affective psychotic disorders, and who therefore should be targeted for intensive preventive interventions.

Acute and transient psychotic disorders (ATPD) are a composite category created in the 10th Edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) to integrate traditional descriptions of acute psychoses, such as the French bouffeé délirante, the German cycloid psychoses, the Scandinavian ’psychogenic psychoses’ and the Japanese ‘atypical psychoses’.1–3 ATPDs are defined in the ICD-10 as psychotic conditions characterized by acute onset (≤15 days) and rapid remission (expected in a period of 1–3 months) that are often triggered by acute stressful events (within two weeks before the onset of the psychotic disorder).1,2,4 The ICD-10 ATPD diagnostic category includes six subtypes categorized by their main features as: ‘acute polymorphic psychotic disorder without symptoms of schizophrenia’ (F23.0) or ‘acute polymorphic psychotic disorder with symptoms of schizophrenia’ (F23.1) which both substantially overlap with classic concepts of bouffée délirante and cycloid psychosis; ‘acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder’ (F23.2) which describes a short-lived schizophrenic episode; ‘acute predominantly delusional psychotic disorder’ (F23.3) which refers to an acute psychotic state featuring relatively stable delusions and/or hallucinations; and the residual subtypes ‘other’ and ‘unspecified’ ATPDs (F23.8–9).2,4 ATPD resolution takes place within one month for subtypes presenting schizophreniform symptoms or three months for subtypes featuring polymorphic, delusional or unspecified characteristics to differentiate them from schizophrenia and persistent delusional disorder, respectively.2,4 All of these clinical characteristics make the ATPD diagnostic category somewhat complex, causing residual classifications (F23.8–9) to be overused in clinical practice.5

ATPDs have traditionally been considered an uncommon psychotic entity with an associated good prognosis.6–8 However, they are not an infrequent diagnosis in clinical practice, accounting for up to 19% of all first-episode psychosis in some cohorts.9,10 In addition, given their high rates of suicidal behavior and their moderate temporal stability (ranging from 52 to 60%), the a priori favorable prognosis of ATPDs is currently under review.11–13 Along this line, most diagnostic transitions appear within two years of onset, mainly toward schizophrenia, and on a lesser scale, to major affective disorders.14 Thus, about half of the cases of ATPD could be considered an early manifestation of a long-lasting psychotic disorder. Moreover, it also has similarities close to the concept of brief limited intermittent psychotic symptoms (BLIPS) in the clinical high-risk state for psychosis (CHR-P) paradigm.5,15,16 Several authors have therefore suggested a revision of the CHR-P criteria including the ICD-10 ATPD category at the same clinical stage as BLIPS, and advocating more intensive intervention in these individuals to prevent risk of progression to schizophrenia and other related disorders.5,15,17 Risk factors of such a diagnostic shift in ATPD are male gender, younger age at onset, poor premorbid adjustment, non-abrupt onset of the psychotic symptoms, and above all, absence of polymorphic psychopathology as well as presence of schizophrenic features.10,18––32 In light of such evidence, the ICD-11 aims to improve the diagnostic validity of the category, by restricting the new description of ATPD to the acute polymorphic psychotic disorder without schizophrenia symptoms (APPD; F23.0), and redistributing the remaining subtypes (F23.1–9) throughout the new Section F2, ‘Schizophrenia and other primary psychotic disorders’.33–35 However, some authorities in the field question the validity of this revision of the ATPD category, suggesting that the definition of APPD does not meet established standards of reliability, because of its shifting psychopathology.36–38 They propose considering the polymorphic symptomatology a supplementary clinical description rather than the core clinical feature of the disorder.37 In addition, several authors have suggested shortening the ATPD temporal criterion to one month to align better with the diagnostic concept of brief psychotic disorder (BPD) listed in the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM), and, thereby, better distinguish ATPD from ICD-schizophrenia.3,36,37,39

The objectives of this study were to evaluate the proportion of diagnostic transitions to schizophrenia and other non-affective psychoses in first-episode ATPD patients over a two-year follow-up period, and to test the replicability of the existing predictors of diagnostic instability in our ATPD cohort. Although other published studies have previously addressed this issue, they have mainly focused on prognostic models of ATPD temporal stability or their risk of psychotic recurrence over time, rather than on the likelihood of diagnostic shift to chronic non-affective psychotic conditions.40,41 In addition, the data for those studies were collected retrospectively from electronic databases and did not examine the reliability/validity of the ATPD diagnoses.40 Therefore, this is the first prospective cohort study to assess the replicability of clinical knowledge about early predictors of diagnostic transition to long-lasting schizophrenia spectrum disorders in a sample of FEP patients with a confirmed ATPD diagnosis.

MethodsSubjects and inclusion/exclusion criteriaA prospective observational study was conducted in a cohort of first-episode psychosis (FEP) patients with a diagnosis of ATPD over a two-year follow-up period. The study sample was recruited from patients aged 18–65 who were treated from 2011 to 2015 by the mental health services at San Juan de la Cruz Hospital (Úbeda) and two community mental health units at the Virgen Macarena University Hospital (Seville). The sum of these centers comprised a catchment area of approximately 500,000 people and represented the sociodemographic characteristics of the general population in Andalusia (Spain) fairly well. All subjects gave their informed consent, and the study was approved by the local ethics committee. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement guidelines were followed in this study.

Data were collected from structured clinical interviews, information from key informants and review of all available medical records. Patients were screened for acute psychotic episodes using the Spanish version of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI).42 Only subjects with a confirmed diagnosis of ATPD (F23.x) were included in this study (i.e., those who achieved full remission from their psychotic episode according to the ICD-10 temporal criteria mentioned above).2 Affective, substance-induced and organic psychotic disorders were excluded also according to ICD-10 guidelines.2 Other exclusion criteria were: past history of psychosis, major or unstable medical condition, central nervous system diseases, history of severe cranioencephalic trauma, diagnosis of cognitive disorder, intellectual disability or pervasive developmental disorder, and not speaking Spanish well enough to complete the evaluation instruments.

Baseline clinical assessmentInformation was collected on the following clinical characteristics and additional diagnostic features: (1) premorbid psychosocial adjustment (assessed using a proxy measure of premorbid adjustment [PMPA] validated in first-episode psychosis patients 43); (2) past psychiatric history; (3) history of substance use (defined as harmful or hazardous use of alcohol, cannabis or other illicit drugs in the last year); (4) first-degree family history of psychosis; (5) ATPD subtype (F23.x); (6) presence of shifting polymorphic symptomatology (i.e. markedly variable psychotic features with perplexity and emotional turmoil changing from day to day or even from hour to hour 2); (7) symptoms of schizophrenia (any of those listed under Criterion G1 for general schizophrenia 2); (8) the presence of associated acute stress (defined as unusually stressful events preceding the onset of psychotic symptoms by one to two weeks 2); and (9) type of onset (abrupt if the change was from a non-psychotic to a clearly psychotic state within 48 h or acute if it developed in over 48 h but less than 2 weeks 2). The sociodemographic variables included were: age, gender, ethnicity (European-Caucasian or other), marital status (unmarried or married/cohabiting), education (higher education, secondary/lower education) and employment status (unemployed or employed). Following the PMPA methodology, the sum of the following sociodemographic variables was used as an indicator of poor premorbid adjustment: being unmarried (or without a partner), unemployed (and not studying), and having a secondary or lower education.43 For further details on the clinical assessment of this sample, see.31,32

Follow-up after onset of psychosisParticipants were followed up over a two-year period while they received multidisciplinary treatment in their community mental health services. Treatment consisted of regular visits to psychiatrist, clinical psychologist, nursing staff and social workers, and included psychopharmacological, psychotherapeutic and psychoeducational intervention. The diagnosis of patients who completed the study period was reviewed following ICD-10 criteria two years after ATPD onset. We reviewed all available information from clinical interviews, key informants, medical records, and visits to general practitioners. As indicated in the aims of the study, patients were classified according to whether they had transited to schizophrenia or other long-lasting non-affective psychoses (ICD-10 codes F20, F22 and F25) or not at the end of the follow-up.2 If patients had unclear or multiple diagnoses at the end of the study period, the authors resolved any discrepancies in the main diagnosis by discussion and consensus. Any patients who did not complete the follow-up or withdrew consent were excluded from analysis.

Statistical analysesA multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to determine which variables independently predicted a diagnostic shift to schizophrenia and other chronic non-affective psychotic conditions. Candidate predictors were selected on the basis of previous studies regarding predictive factors of ATPD diagnostic instability and included male gender, younger age at onset, poor premorbid adjustment, non-abrupt onset of the psychotic symptomatology, absence of polymorphic features, and presence of symptoms of schizophrenia.10,18–32 In addition, a separate univariate analysis was performed for each candidate predictor to test for unadjusted differences between groups.

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the baseline characteristics of the study population. Means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables were calculated for all clinical and demographic variables. Normal distribution of the data was examined with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The Chi-Square test and Fisher's exact test (with Freeman–Halton extension) were used to determine the association between categorical variables, and one-way ANOVA for continuous variables. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated using binary logistic regression analyses. Multicollinearity among any of the predictor variables of the multivariate model was examined using a correlation matrix while the model's overall predictive accuracy was calculated by using a classification table.44,45 The Nagelkerke R2 was used to estimate the percentage of variance explained by the model.46 Receiver-operating characteristics (ROC) curves and the area under the curve (AUC) were computed to assess the model´s discriminatory power, whereas its internal validation was assessed by bootstrapping.47,48 Significance was set at p < 0.05. Listwise deletion was used to deal with missing data.49 Analyses were performed using the MedCalc Statistical Software (version 19.0.7; MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium).

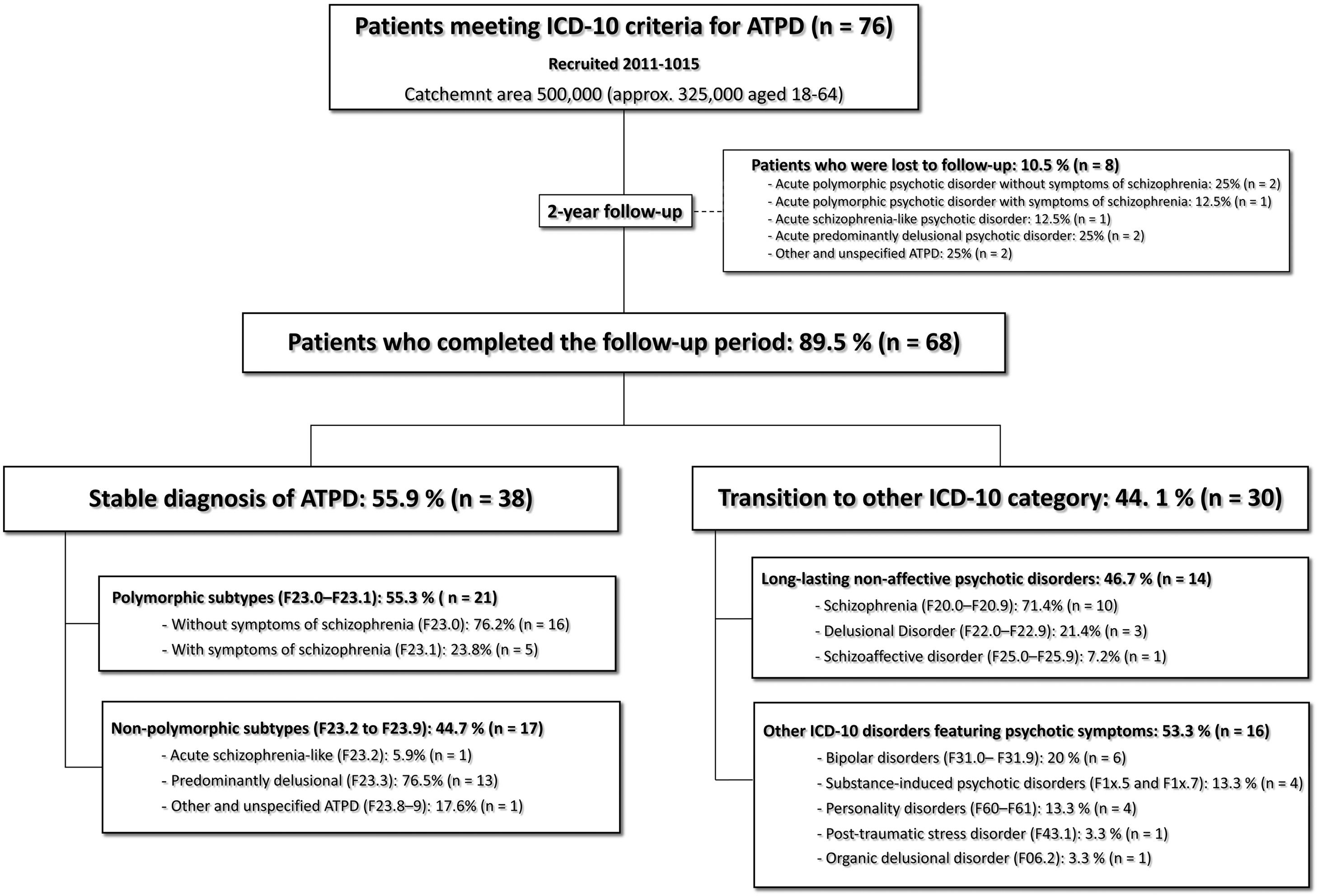

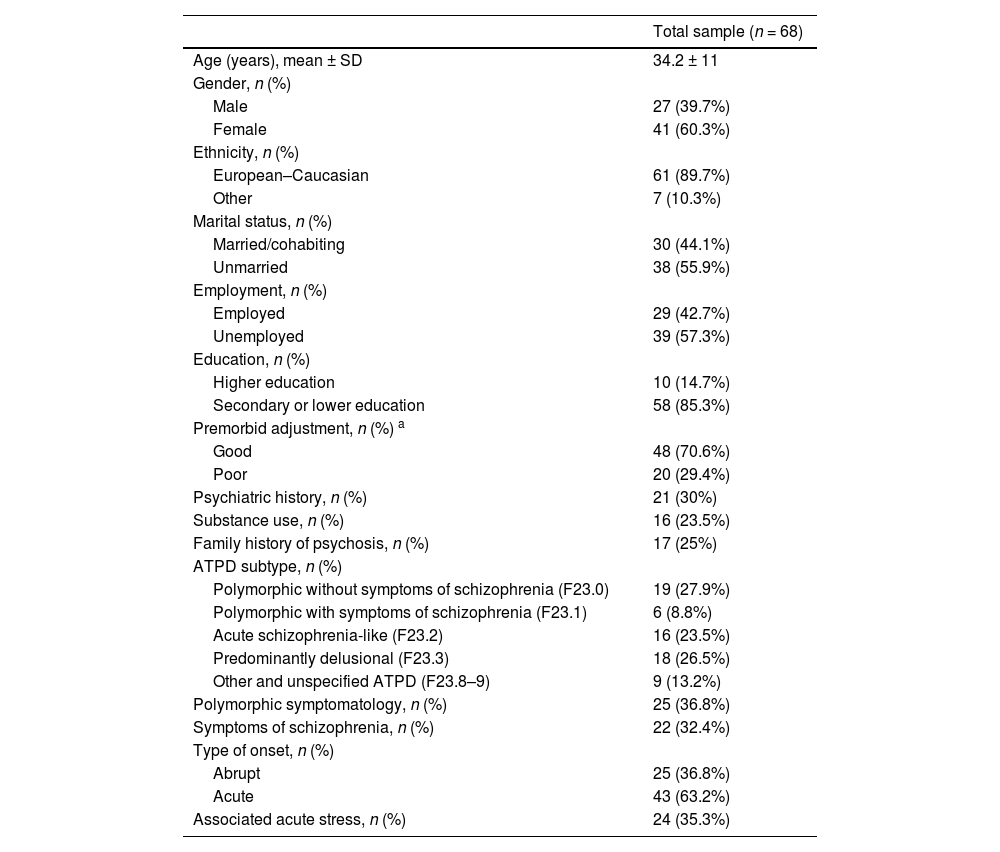

ResultsSample characteristicsFig. 1 illustrates patient diagnostic trajectories during the follow-up period and Table 1 shows their baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. A total of 76 individuals with FEP met the ICD-10 criteria for ATPD from 2011 to 2015. Of them, 68 patients (89.5%) completed the two-year follow-up period while the remaining eight (10.5%) dropped out before its completion and were excluded from the analysis. The final study sample therefore comprised 68 subjects (27 males, 41 females) with a mean age of 34.2 years (SD ± 11, range 18–60). The majority of the cohort were European–Caucasian (89.7%, n = 61). Other most frequent sociodemographic characteristics were: unmarried (55.9%, n = 38), unemployed (57.3%, n = 39) and secondary or lower education (85.3%, n = 58). Almost a third of the patients (29.4%; n = 20) were rated as having poor premorbid adjustment, 25% (n = 17) had a first-degree family history of psychosis, 30% (n = 21) a previous psychiatric history, and 23.5% (n = 16) also had a history of substance use. The baseline diagnostic distribution of ATPD subtypes was as follows: APPD (F23.0) 27.9% (n = 19), ‘acute polymorphic psychotic disorder with symptoms of schizophrenia’ (F23.1) 8.8% (n = 6), ‘acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder’ (F23.2) 23.5% (n = 16), ‘acute predominantly delusional psychotic disorder’ (F23.3) 26.5% (n = 18) and ‘other and unspecified ATPD’ (F23.8–9) 13.2% (n = 9). Polymorphic features were identified in 36.8% (n = 25) of patients, symptoms of schizophrenia in 32.4% (n = 22), abrupt onset of the pyschotic symptomatology in 36.8% (n = 25) and associated acute stress in 35.3% (n = 24). Data on other clinical characteristics are available in previous publications.31,32

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

| Total sample (n = 68) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 34.2 ± 11 |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 27 (39.7%) |

| Female | 41 (60.3%) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| European–Caucasian | 61 (89.7%) |

| Other | 7 (10.3%) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Married/cohabiting | 30 (44.1%) |

| Unmarried | 38 (55.9%) |

| Employment, n (%) | |

| Employed | 29 (42.7%) |

| Unemployed | 39 (57.3%) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Higher education | 10 (14.7%) |

| Secondary or lower education | 58 (85.3%) |

| Premorbid adjustment, n (%) a | |

| Good | 48 (70.6%) |

| Poor | 20 (29.4%) |

| Psychiatric history, n (%) | 21 (30%) |

| Substance use, n (%) | 16 (23.5%) |

| Family history of psychosis, n (%) | 17 (25%) |

| ATPD subtype, n (%) | |

| Polymorphic without symptoms of schizophrenia (F23.0) | 19 (27.9%) |

| Polymorphic with symptoms of schizophrenia (F23.1) | 6 (8.8%) |

| Acute schizophrenia-like (F23.2) | 16 (23.5%) |

| Predominantly delusional (F23.3) | 18 (26.5%) |

| Other and unspecified ATPD (F23.8–9) | 9 (13.2%) |

| Polymorphic symptomatology, n (%) | 25 (36.8%) |

| Symptoms of schizophrenia, n (%) | 22 (32.4%) |

| Type of onset, n (%) | |

| Abrupt | 25 (36.8%) |

| Acute | 43 (63.2%) |

| Associated acute stress, n (%) | 24 (35.3%) |

Abbreviations: ATPD, acute and transient psychotic disorder; SD, standard deviation.

Fig. 1 compares diagnoses at the end of the study period. Thirty-eight patients (55.9%) maintained their initial ATPD diagnosis after the two-year follow-up. On the contrary, a diagnostic revision from ATPD to some other ICD-10 category was necessary in thirty subjects (44.1%). Within the group of diagnostic change, the majority of patients (46.7%) transited to long-lasting non-affective psychoses (ICD-10 codes F20, F22 and F25), of whom 71.4% shifted to schizophrenia. Other diagnostic revisions were toward bipolar disorder (20%), substance-induced psychotic disorder (13.3%), personality disorder (13.3%), post-traumatic estress disorder (3.3%) and organic delusional disorder (3.3%). In all these cases, after longitudinal analysis of the course of the illness, the original symptomatology of the first episode of ATPD was explained better within the context of such mental disorders. Additional details on the diagnostic stability of ATPD over time have been published previously.31,32

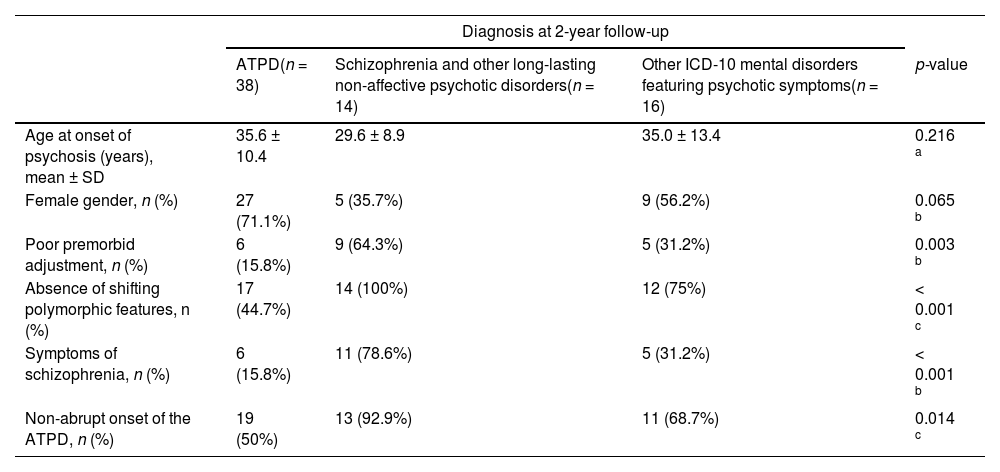

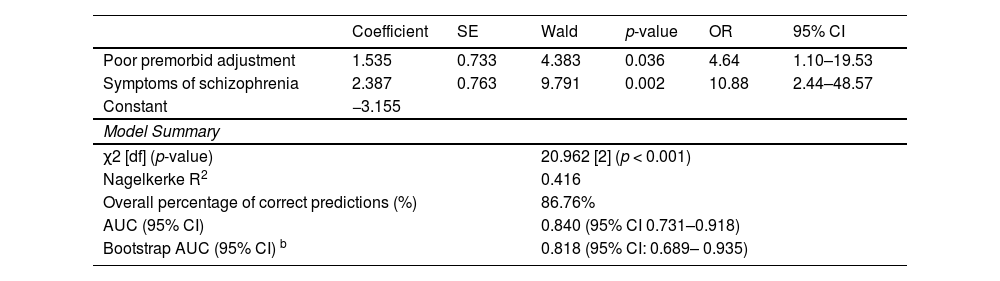

Predictors of diagnostic change to schizophrenia and other non-affective psychosesResults of univariate analysis and multivariate logistic regression are presented in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Statistical tests for univariate analysis showed that, with the exception of age (p < 0.216) and gender (p < 0.065), the other prior knowledge factors related to ATPD diagnostic instability were significantly associated (p < 0.05) with a later transition to long-lasting non-affective psychotic disorders. Multivariate logistic regression analysis yielded a final model in which poor premorbid adjustment (OR = 4.64, 95% CI 1.10–19.53; p = 0.036) and presence of symptoms of schizophrenia (OR = 10.88, 95% CI 2.44–48.57; p = 0.002) were independently significantly associated with diagnostic shift to schizophrenia and other persistent non-affective psychotic conditions. None of the other prior knowledge factors yielded significant independent associations. Examination of the correlation matrix indicated no collinearity issues between covariates. The multivariate model was statistically significant (χ2 = 20.962 [2], p < 0.001) and accounted for 41.6% (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.416) of the variance. The overall percentage of correct predictions was 86.76% and the AUC of the model was 0.840 (95% CI 0.731–0.918), revealing excellent discriminatory ability. After correction for overfitting and optimism by bootstrapping, the adjusted AUC of the model was 0.818 (95% CI: 0.689–0.935), indicating good internal validity.

Results of univariate analysis for each candidate predictor: Unadjusted between-group comparisons.

| Diagnosis at 2-year follow-up | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATPD(n = 38) | Schizophrenia and other long-lasting non-affective psychotic disorders(n = 14) | Other ICD-10 mental disorders featuring psychotic symptoms(n = 16) | p-value | |

| Age at onset of psychosis (years), mean ± SD | 35.6 ± 10.4 | 29.6 ± 8.9 | 35.0 ± 13.4 | 0.216 a |

| Female gender, n (%) | 27 (71.1%) | 5 (35.7%) | 9 (56.2%) | 0.065 b |

| Poor premorbid adjustment, n (%) | 6 (15.8%) | 9 (64.3%) | 5 (31.2%) | 0.003 b |

| Absence of shifting polymorphic features, n (%) | 17 (44.7%) | 14 (100%) | 12 (75%) | < 0.001 c |

| Symptoms of schizophrenia, n (%) | 6 (15.8%) | 11 (78.6%) | 5 (31.2%) | < 0.001 b |

| Non-abrupt onset of the ATPD, n (%) | 19 (50%) | 13 (92.9%) | 11 (68.7%) | 0.014 c |

Abbreviations: ATPD, acute and transient psychotic disorder; ICD-10, Tenth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases; SD, standard deviation.

Predictors of diagnostic transition to schizophrenia and other long-lasting non-affective psychotic disorders: results of multivariate logistic regression analysis a.

| Coefficient | SE | Wald | p-value | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor premorbid adjustment | 1.535 | 0.733 | 4.383 | 0.036 | 4.64 | 1.10–19.53 |

| Symptoms of schizophrenia | 2.387 | 0.763 | 9.791 | 0.002 | 10.88 | 2.44–48.57 |

| Constant | −3.155 | |||||

| Model Summary | ||||||

| χ2 [df] (p-value) | 20.962 [2] (p < 0.001) | |||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.416 | |||||

| Overall percentage of correct predictions (%) | 86.76% | |||||

| AUC (95% CI) | 0.840 (95% CI 0.731–0.918) | |||||

| Bootstrap AUC (95% CI) b | 0.818 (95% CI: 0.689– 0.935) | |||||

Abbreviations: ATPD, acute and transient psychotic disorder; AUC, area under the curve; df, degree of freedom; OR, odds ratio; SE, standard error; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval.

The aims of this study were to explore the proportion of diagnostic revision to schizophrenia and other long-lasting non-affective psychotic disorders in a cohort of patients with first-episode ATPD after a two-year follow-up period, and to examine the replicability of previous findings on early predictors of ATPD diagnostic shift. The main findings were that the initial ATPD diagnosis of almost half of the patients was revised, the majority (46.7%) toward schizophrenia and other long-lasting non-affective psychoses. Poor premorbid adjustment and the presence of schizophreniform symptoms at onset of psychosis significantly independently predicted a diagnostic shift to such persistent psychotic conditions. Other potential prognostic variables such as male gender, younger age at onset, non-abrupt onset of psychosis and the absence of polymorphic features were not statistically independently associated with a diagnostic transition from ATPD to enduring non-affective psychotic disorders. To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study examining the validity of existing predictors of diagnostic shift to schizophrenia and other primary psychotic disorders in patients with first-episode of ATPD.

The epidemiological characteristics of our ATPD cohort were generally consistent with previous literature, although some findings merit further discussion. The mean age of our sample (34.2 ± 11 years) was higher than in other ATPD cohorts,22,50,51 but in line with what has been observed in large-scale epidemiological studies on first-episode ATPD.5,6,20 The female preponderance in our cohort (60.3%) contrasted with the almost equal distribution observed in other ATPD samples.5,6,20 However, several ATPD studies have reported similar or even higher female-to-male ratios.22,24,30 Regarding clinical features, the proportion of ATPD polymorphic subtypes (36.8%) was lower than reported by other authors.22,24,30 However, diversity in the frequency of ATPD subtypes featuring polymorphic, schizophrenic, and predominantly delusional symptoms is observed in the literature.14 Lastly, our dropout rate (10.5%) was substantially lower than usually reported in FEP and ATPD studies with the same follow-up period as ours,22,52 although other authors have also reported similarly low dropout rates at two years in patients with short-lived psychotic disorders.53

The proportion of diagnostic transitions to long-lasting non-affective psychoses in our ATPD cohort as well as our findings regarding the prognostic role of premorbid adjustment and symptoms of schizophrenia were in agreement with the extant literature.5,10,14,19,22,24–26,30 Along this line, poor premorbid psychosocial adjustment is a well-known precursor of schizophrenia and other enduring psychoses, not only in patients with ATPD, but also in those with FEP and individuals at CHR-P.10,24,25,54,55 Similarly, the presence of symptoms of schizophrenia at the onset of psychosis is a well-recognized risk factor for subsequent progression to schizophrenia, not only in the specific context of ATPD, but also in both FEP and CHR-P populations.16,18,22,26,29,30 Interestingly, the absence of shifting polymorphic symptomatology, although statistically associated with a risk of transition to schizophrenia-spectrum disorders in univariate comparisons, ceased to be significant in multivariate analysis once the effects of other covariates on the outcome variable had been controlled for. This finding contrasts with our earlier study, in which polymorphic features were a significant independent prognostic factor favorable to diagnostic stability in ATPDs.31 The lack of statistical significance in the multivariate analysis observed in the present study could be explained by our small sample size. However, it may also reflect mediating or confounding effects through other processes, such as deficits in premorbid adjustment, when the outcome of interest is the diagnostic transition to schizophrenia and other persistent non-affective psychoses, rather than just ATPD temporal stability/instability.56 In this regard it should be noted that we also recorded diagnostic shifts over time to bipolar, substance-induced, personality and post-traumatic stress disorders, and that patients with these mental disorders have fewer premorbid adjustment deficits than those with schizophrenia.57 This would explain why premorbid adjustment was a statistically significantly independent predictor, to the detriment of polymorphic symptomatology, in the present model. Even though previous studies have shown that the prognostic value of male gender and younger age at onset are strongly related to diagnostic shift in ATPD, we did not find any independent association between these variables and subsequent diagnostic revision to chronic non-affective psychoses.10,18–23 This could also be related to our sample size, but a previous study by Fusar-Poli et al. found results similar to ours, in which neither gender nor age had significant roles in the longitudinal diagnostic stability of ATPDs.13 Similarly, male gender and younger age have yielded mixed results as prognostic factors for psychotic recurrence in individuals with a brief psychotic episode.3 Finally, the non-abrupt onset of the psychotic symptomatology did not yield significant independent contributions to predicting diagnostic shifts to schizophrenia or other non-affective psychoses in our multivariate model. Albeit contrary to the above-mentioned previous knowledge,26,27 other authors have not found associations between acuteness of onset of ATPD and the risk for a later progression to schizophrenia-spectrum disorders either.10,30

Methodological limitationsSome methodological limitations should be taken into account. Our sample size was quite small, particularly in the schizophrenia and other enduring psychoses group, and our follow-up period was relatively short compared to other studies.5 The latter may be an important limitation, given that although most diagnostic transitions in ATPD tend to occur in the first two years,14 diagnostic changes may still be observable even 10 years after the psychotic onset.23 Standardized psychometric assessment scales for measuring the type and severity of psychotic symptomatology and premorbid psychosocial functioning ratings are lacking. Although a duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) of over one month and a prolonged duration of hospitalization have been found to predict subsequent transitions to schizophrenia in patients with ATPD,20–22,26,58 our records did not always include this information, and therefore, the role of these variables could not be examined. Lastly, since the purpose of this study was to test the validity of existing knowledge about baseline predictors of diagnostic change to schizophrenia and other primary psychotic disorders, neither the prognostic role of the antipsychotic treatment received nor the role of subsequent psychotic relapses during the follow-up period were analyzed. However, there are studies along this line suggesting that a high antipsychotic load at hospital discharge and later appearance of psychotic recurrences could increase the likelihood of conversion to persistent psychotic disorders in patients with ATPDs.21,59

Implications for clinical practice and future directionsIn spite of the limitations mentioned above, the results of this study have a number of relevant clinical implications. First of all, they could enable early identification of patients with first-episode ATPD at most risk of developing schizophrenia and other enduring non-affective psychoses, and thereby guide clinicians in designing multimodal long-term treatment strategies to prevent relapse and clinical deterioration in these at-risk individuals. Furthermore, because of the general concordance between the ICD-10 ATPD and the DSM BPD categories, our results may also be extrapolated to that population.60 Similarly, the findings of our study could facilitate development of more accurate preventive intervention for patients who are attended for CHR-P meeting BLIPS criteria.3,16 On the other hand, our data regarding the predictive capabilities of premorbid adjustment in ATPDs highlight the importance of assessing premorbid psychosocial functioning in all patients experiencing FEP, as it may be an indicator of neurodevelopmental abnormalities and a potential precursor of schizophrenia in this population.57,61–63 Moreover, our results regarding the unfavorable prognostic role of schizophrenic features in ATPD patients contribute to the ongoing discussion surrounding the importance of first rank symptoms (FRS) in the schizophrenia diagnosis.64,65 Even though FRS can occur in a wide variety of mental disorders, they remain as one of the core defining features of schizophrenia in the ICD-10 criteria to the extent that their absence would support the diagnosis of other forms of psychosis rather than schizophrenia.65,66 Our findings are not only consistent with this, but also suggest that the presence of FRS in short-lived psychotic disorders such as ATPDs represents a predictive factor for a later transition to schizophrenia. Finally, these results support the ICD-11 guidelines excluding subtypes with schizophrenic features from the forthcoming ATPD category, which will be collapsed within the new F2 section under the name ‘unspecified primary psychotic disorders’.33–35

Further studies on short-lived psychotic disorders are still needed to examine the reliability and validity of our findings in patients with BPD according to DSM criteria and in individuals at CHR-P who meet BLIPS criteria, since both concepts overlap considerably with the ICD-10 ATPD description.3,16,60 Future efforts should also be aimed at exploring whether the type and severity of schizophrenic features could provide us with more accurate prognostic information for individuals with first-episode ATPD. Likewise, it may be of interest to study the predictive role of other key domains, such as negative symptoms, cognitive dysfunctions, insight impairments and the subjective quality of life in this population. Lastly, in view of the ongoing debate on when to start and discontinue antipsychotics in individuals with ATPD,3 additional research should be undertaken to examine the effects of antipsychotic maintenance treatment on diagnostic stability and risk of psychotic relapse in these patients.

In conclusion, almost half of the cases of ATPD are an early manifestation of some other mental disorder, mostly schizophrenia-spectrum. Those individuals with first-episode ATPD presenting poor premorbid adjustment and symptoms of schizophrenia are at the most risk for developing persistent non-affective psychotic disorders, and therefore, they would be the subgroup of patients most likely to benefit from more intensive intervention.

Author contributionÁlvaro López-Díaz designed the study, recruited patients, collected the data, managed the analyses, interpreted the results and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Jose Luis Fernández-González and Ignacio Lara contributed to patient recruitment and data collection. Benedicto Crespo-Facorro contributed to manuscript revision and study supervision. Miguel Ruiz-Veguilla supervised the study design, data interpretation and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the article critically and have approved the final manuscript.

Data availabilityThe data will be available upon request from the authors.

Ethical considerationsThe study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All subjects gave their informed consent. Ethical approval was obtained from the local ethics committee.