To study (1) comparative prevalence of non-psychotic morbidity (NPM) in male dissocial personality disorder (DPD) patients with or without psychoactive substance dependence (SD).

(2) Relationship of NPM with pattern and duration of SD.

MethodsThis was a 20-month single blind cross sectional hospital-based study with a sample size of total 1036 male prisoners ≥18 years of age suffering from DPD (study=518, control=518). Participants in study group fulfilled further criteria of being suffering from SD.

ResultsMajority of participants in both groups were unemployed, married individuals with occupational skills of less than skilled labour level and educational attainment of higher secondary level or lesser. Intensity of substance use was higher in study participants with NPM than those without NPM, and they started consuming substance at younger age, had a longer duration of substance use and dependence, and majority of them had onset of NPM after onset of SD. NPM was present in 350 (67.6%) of study participants against 159 (30.7%) in controls. Study participants had especially high prevalence of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD)/Recurrent Depressive Disorder (RDD) (24.9%) and Adjustment Disorder (13.3%). Among study participants, 203 (58%) participants with NPM used ≥3 psychoactive substances against 33 (19.7%) in those without NPM.

ConclusionsThe results suggested that a higher burden of NPM exists in substance using DPD population than those without NPM and occurrence of NPM in turn leads to earlier onset and increased severity of SD in this population.

Personality disorder (PD) affects 6% of the world population, and the differences between countries show no consistent variation.1 PD leads to a disturbance in functioning as great as that in most major mental disorders.2

Dissocial PD (DPD) is associated with high rates of separation and divorce; unemployment and inefficiency; and poor quality of life for the individual and his/her family.3 Offenders with DPD are usually young, have a high suicide risk, high rate of mood, anxiety, substance use, psychotic, somatoform disorders, borderline personality disorder, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).6 Health care utilization by DPD patients is excessive.3

In a study, 10% of male prisoners were found to be suffering from personality disorder.7 More antisocial acts were perpetrated by alcohol and drug users than by nonusers and main risk factors for perpetrating antisocial acts were being male, using alcohol and other drugs.8 Almost 47–63% of male prisoners and 21–31% of female prisoners had DPD.9 Similarly, the prevalence of DPD is higher among patients in alcohol or other drug (AOD) abuse treatment programs than in the general population,10 suggesting a link between DPD and AOD abuse and dependence. Offenders with DPD are more likely to have substance use disorder.4,11–13 Since very few of these studies have employed standardized interviews; hence underestimation of PD prevalence cannot be ruled out. DPD is significantly associated with persistent alcohol, cannabis and nicotine use disorders (adjusted odd ratios 2.46–3.51) then general population.

Prisoners are several times more likely to have psychosis and major depression, and about ten times more likely to have DPD than the general population.14

Some of the problems in studying various clinical aspects related with DPD have been (a) it is only in recent times that a consensus has emerged for the definition of DPD. The studies carried out until recently have employed variable definition of DPD. (b) Other sources of variation include variable expertise of therapist, sampling techniques, geographical variations and time period of the study.

Although only about one-third of the world's prisoners live in western countries, about 99% of available data from prison surveys are derived from western populations, which underscores the need for greater forensic psychiatric research in non-western populations.14 Literature from India in this area is scanty.

ObjectivesTo study (1) comparative prevalence of NPM in male DPD patient with or without SD (2) relationship of NPM with pattern and duration of SD.

MethodsThis was a 20-month single blind cross sectional hospital-based study with a convenience sample size of total 1036 participants (study=518, control=518). This study was conducted at Central Jail Hospital (CJH), New Delhi which is largest prison hospital setting in India with both inpatient and outpatient departments. Prior to initiation of study approval in this regard was obtained from Ethical committee of CJH after protocol presentation.

Inclusion criteria- 1.

Prisoners diagnosed to be suffering from both substance dependence and DPD by ICD-10 (DCR) criteria in past one month.

- 2.

Male participant.

- 3.

Age 18 years or above.

- 4.

Participant willing to give a written informed consent.

- 1.

Participants who were not co-operative for the interview for study purposes, as per the clinical judgement of the researcher. The rationales behind the clinical judgements of researcher were recorded.

- 2.

Inability to speak sufficient English or Hindi.

- 3.

Those participants with severe physical illness (like hepatic encephalopathy, severe debilitating illness) or severe cognitive illness (with Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE) score<23) that might have hampered the assessment process.

- 4.

Lifetime diagnosis of psychosis and/or Bipolar Affective Disorder (BPAD).

- 5.

Participants currently suffering from personality disorder except DPD as per International Personality Disorder Examination (IPDE).

Participants found matching with study participants on socio-demographic and clinical parameters except presence of psychoactive SD.

Instrument used: (a) International personality disorder examination (IPDE): semi-structured interview using ICD-10 criteria has 67 set of questions and time required in its completion is 150min.15 In participants who were unable to understand English, North Indian Hindi translation which was standardized and used in previous studies was used.16

(b) Basic socio-demographic Performa: it included questions to obtain information regarding socio-demographic characteristics of SD. Socio-demographic characteristics such as age, sex, marital status, education, occupation, employment status, religion and residence were recorded.

(c) The mini-mental state examination: The MMSE is a 30-point questionnaire test designed by Folstein et al. that is used to screen for cognitive impairment. Each component is rated from 0 to 1. In the time span of about 10min it samples various functions including orientation, memory, arithmetic skills, language use and comprehension and basic motor skills. Cognitive deficits in participants were ruled out using MMSE.17

(d) Schedule for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN): the assessment of psychiatric morbidity in participants was performed by a SCAN-based clinical interview in which clinical interview.18

(e) The Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS): the SDS developed by Gossop et al. was used to rate severity of substance dependence in individuals. It is a 5-item scale that measures the degree of psychological dependence specifically related to the individual's feeling of impaired control over and preoccupation and anxiety towards drug taking. Score of each item ranges from 0 to 3.19

The psychiatric diagnosis in the present study was made as per ICD-10 (DCR) criteria. The data so generated was then subjected to statistical analysis.5

Assessment procedureParticipants fulfilling study criteria were included in the study after obtaining a written informed consent for the same. The physical examination and MMSE screening of the participants were done to make the necessary exclusion. Assessment tools were applied in the order starting from the Performa to assess the socio-demographic characteristics, SCAN, IPDE and SDS. Application of all these tools was only done by single trained psychiatrists involved in the study. Confidentiality and privacy were maintained during the assessment. During assessment if author came across any information which might have helped in better treatment of patient then those details were provided to respective treating team.

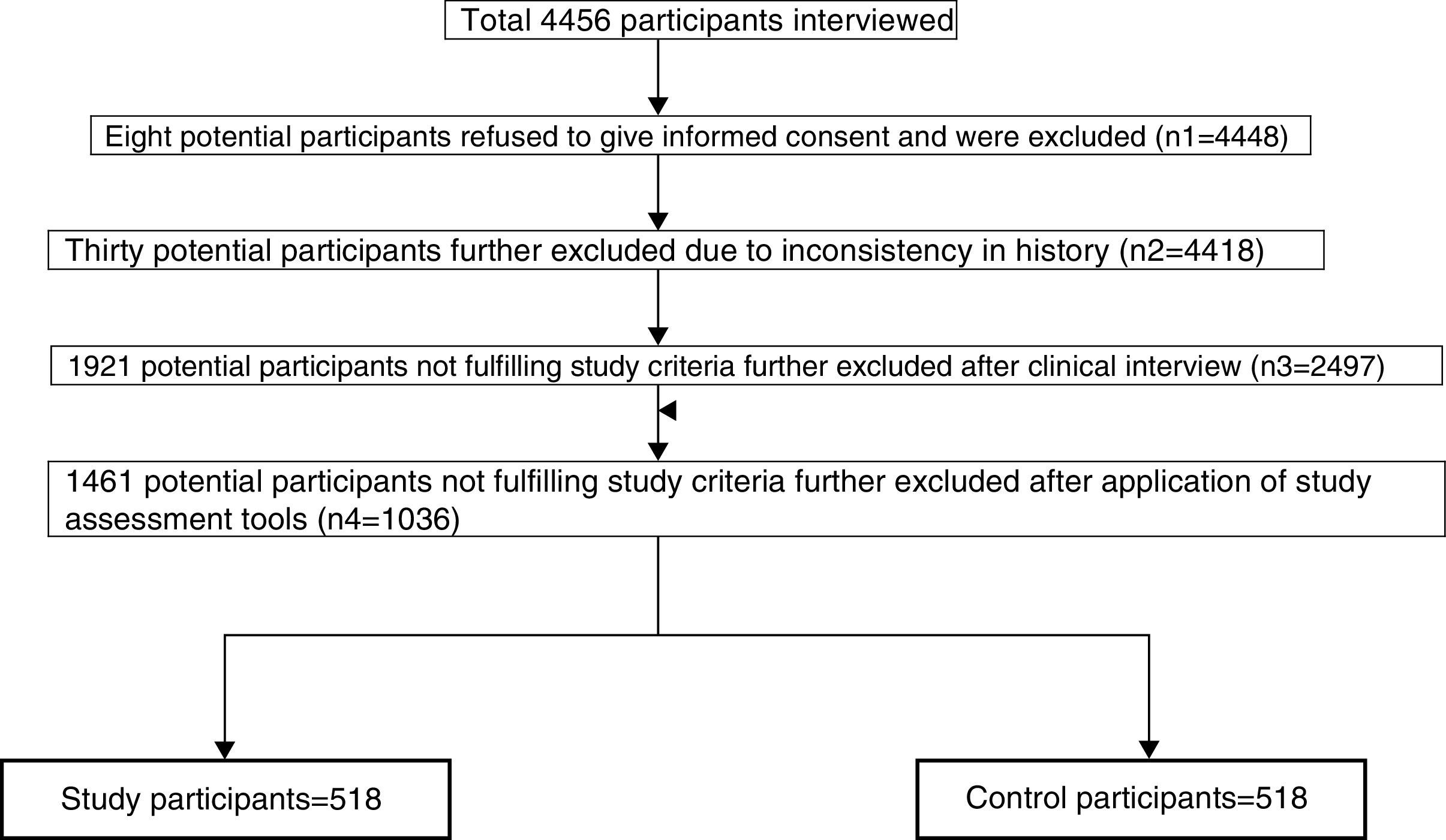

Statistical analysis and data collectionData were entered in the data-based computer program and were analyzed using the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS 15.0.1).20 Descriptive (frequency and percentage) and inferential statistics (Chi-square test and t-test) were used to interpret the data. A ‘p value’ of <0.05 is considered as significant (Fig. 1).

ResultsTotal 4456 prisoners were interviewed out of which 3420 were excluded because of following reasons: (1) eight (five in study and three in control group) for refusal to give consent for study related assessment, (2) thirty due to inconsistency in history and inability to recall some/multiple past details with potential bearing on current study, (3) 1921 individuals after clinical interview as were unlikely to fulfil study criteria and (4) 1461 after assessment were not fulfilling study criteria (mostly diagnosis of DPD). Among 1921 individuals were excluded after clinical interview, and thirty were either suffering from psychosis/BPAD or had lifetime history of psychosis/BPAD.

According to Table 1, mean age±SD of study participants was 38.3±10 which was similar to finding of control participants (39.2±10.6). The difference in age of study and control participants was statistically insignificant (t=1.41, p-value=0.16, SE of difference=0.64).

Socio-demographic profile of study and control participants.

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean±SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of study participants in yrs | 518 | 23 | 63 | 38.3±10.0 |

| Age of control participants in yrs | 518 | 22 | 64 | 39.2±10.6 |

| Number of study participants (n=518) | Percentage (%) | Number of control participants (n=518) | Percentage (%) | χ2 value | df | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | |||||||

| Illiterate | 106 | 20.5 | 95 | 18.3 | 0.28 | 3 | 0.42 |

| Under-metric | 146 | 28.2 | 153 | 29.5 | |||

| Graduate and above | 106 | 20.5 | 99 | 19.1 | |||

| Occupation | |||||||

| No occupation | 126 | 24.3 | 136 | 26.3 | 3.46 | 6 | 0.75 |

| Unskilled | 135 | 26.1 | 126 | 24.3 | |||

| Semi-skilled worker | 125 | 24.1 | 118 | 22.8 | |||

| Skilled | 35 | 6.8 | 40 | 7.7 | |||

| Professional | 34 | 6.6 | 39 | 7.5 | |||

| Business | 36 | 6.9 | 35 | 6.8 | |||

| Student | 27 | 5.2 | 24 | 4.6 | |||

| Employment | |||||||

| Unemployed | 288 | 55.6 | 284 | 54.8 | 0.13 | 1 | 0.72 |

| Employed | 230 | 44.4 | 234 | 45.2 | |||

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married | 275 | 53.1 | 274 | 52.9 | 3.3 | 2 | 0.19 |

| Unmarried | 189 | 38.2 | 177 | 32.2 | |||

| Separated/Widowed | 54 | 8.7 | 67 | 14.9 | |||

p-Value less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Majority of participants were unemployed married individuals who did not have educational skills of more than higher secondary and occupational skills of more than unskilled labour level. No statistical difference was found between two groups in terms of socio-demographic variables.

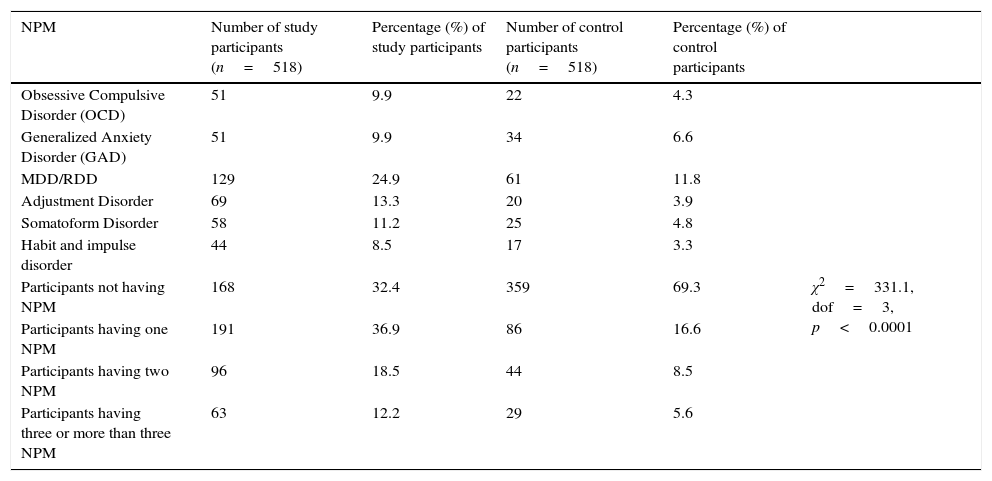

According to Table 2, difference between prevalence of NPM in study and control participants was statistically significant (χ2 value 331.1; dof 3, p value 0.0001). Prevalence of MDD/RDD (24.9%) and adjustment disorder (13.3%) in study participants was much higher than in control participants.

Prevalence of NPM in study and control participants.

| NPM | Number of study participants (n=518) | Percentage (%) of study participants | Number of control participants (n=518) | Percentage (%) of control participants | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) | 51 | 9.9 | 22 | 4.3 | |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) | 51 | 9.9 | 34 | 6.6 | |

| MDD/RDD | 129 | 24.9 | 61 | 11.8 | |

| Adjustment Disorder | 69 | 13.3 | 20 | 3.9 | |

| Somatoform Disorder | 58 | 11.2 | 25 | 4.8 | |

| Habit and impulse disorder | 44 | 8.5 | 17 | 3.3 | |

| Participants not having NPM | 168 | 32.4 | 359 | 69.3 | χ2=331.1, dof=3, p<0.0001 |

| Participants having one NPM | 191 | 36.9 | 86 | 16.6 | |

| Participants having two NPM | 96 | 18.5 | 44 | 8.5 | |

| Participants having three or more than three NPM | 63 | 12.2 | 29 | 5.6 |

Note: some participants had more than one psychiatric disorder.

According to Table 3, the mean score±SD score of study participants having NPM on SDS scale was 10.41±1.34 against 8.5±1.6 in those without NPM. Considering maximum possible score on SDS of 15 in an individual, there was severe substance dependence among study participants. The difference in SD score of psychoactive substance using participants with and without NPM was statistically significant (p value<0.0001, t=14.24, SE of difference=0.13).

Substance use characteristics – I.

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean±SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDS score of study participants not having NPM | 168 | 6.4 | 10.5 | 8.5±1.16 |

| Study participants having NPM | ||||

| SDS score of study participants having one NPM | 191 | 8.1 | 11.8 | 9.99±1.1 |

| SDS score of study participants having two NPM | 96 | 8.9 | 12.3 | 10.59±0.91 |

| SDS score of study participants having three or more NPM | 63 | 9.6 | 12.9 | 11.4±0.83 |

| Total | 350 | 8.1 | 12.9 | 10.41±1.34 |

According to Table 4, study participants with NPM compared to those without NPM start consuming substance at younger age as well as have greater duration of substance use and dependence and this difference was statistically significant.

Substance use characteristics – II.

| Years | Number of study participants with NPM (n=350) | Percentage of study participants with NPM | Number of study participants without NPM (n=168) | Percentage of study participants without NPM | χ2 value | dof | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of onset of substance use | 10–20 | 115 | 32.9 | 60 | 35.7 | 9.84 | 3 | 0.02 |

| 20–30 | 123 | 35.1 | 64 | 38.1 | ||||

| 30–40 | 60 | 17.1 | 32 | 19 | ||||

| 40–50 | 52 | 14.9 | 12 | 7.1 | ||||

| Duration of substance use | 0–5 | 63 | 18.0 | 37 | 22.0 | 9.97 | 4 | 0.04 |

| 6–10 | 70 | 20.0 | 42 | 25.0 | ||||

| 11–15 | 88 | 25.1 | 49 | 29.2 | ||||

| 16–20 | 96 | 27.4 | 28 | 16.7 | ||||

| >20 | 33 | 9.4 | 12 | 7.1 | ||||

| Duration of substance dependence | 0–5 | 119 | 34 | 64 | 38.1 | 14.68 | 3 | 0.002 |

| 6–10 | 147 | 42 | 79 | 47 | ||||

| 11–15 | 59 | 16.9 | 22 | 13.1 | ||||

| 16–20 | 25 | 7.1 | 3 | 1.8 |

Table 5 depicts that among study participants with NPM, majority i.e. 61.4% had onset of NPM after onset of SD which points towards possible contribution of SD to onset of NPM.

According to Table 6, more than 80% study participants with NPM were suffering from alcohol, opioid and cannabis dependence either alone or in various combinations. Number of participants with use of three or more than three substances at a time was much more common in study participants with NPM than in those without NPM. Difference between substance consumption pattern of participants with and without NPM was found to be statistically significant (χ2 value=96.53; dof=3; p<0.0001). Among study participants, cannabis dependence is most common (68.3%) followed by opioid (61.1%) and alcohol (60.3%). While among control participants, alcohol dependence is most common (76.8%) followed by cannabis (62.5%) and opioid (56%).

Prevalence of various psychoactive substance use/dependence in study participants.

| Psychoactive substance | Number of study participants suffering from NPM (n=350) | Percentage in study participants suffering from NPM | Number of study participants not suffering from NPM (n=168) | Percentage in study participants not suffering from NPM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants with dependence to one substance | Alcohol dependence | 8 | 2.4 | 16 | 9.5 |

| Cannabis dependence | 0 | 0 | 16 | 9.5 | |

| Opioid dependence | 8 | 2.4 | 20 | 11.9 | |

| Benzodiazepine dependence | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other substance dependence | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 16 | 4.8 | 52 | 31.0 | |

| Participants with dependence to two substance | Alcohol and cannabis dependence | 13 | 3.7 | 19 | 11.3 |

| Alcohol and opioid dependence | 21 | 6.1 | 19 | 11.3 | |

| Alcohol and benzodiazepine dependence | 21 | 6.1 | 16 | 9.5 | |

| Alcohol and other substance dependence | 17 | 4.8 | 6 | 3.6 | |

| Cannabis and opioid dependence | 24 | 6.9 | 11 | 6.5 | |

| Cannabis and benzodiazepine dependence | 16 | 4.5 | 6 | 3.6 | |

| Cannabis and other substance dependence | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Opioid and benzodiazepine dependence | 0 | 0 | 6 | 3.6 | |

| Opioid and other substance dependence | 17 | 4.8 | 0 | 0 | |

| Benzodiazepine and other substance dependence | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 129 | 36.9 | 85 | 50.6 | |

| Participants with dependence to three substance | Alcohol, opioid and cannabis dependence | 34 | 9.6 | 16 | 9.5 |

| Alcohol, cannabis and benzodiazepine dependence | 25 | 7.2 | 11 | 6.5 | |

| Alcohol, cannabis and other substance dependence | 34 | 9.6 | 0 | 0 | |

| Cannabis, opioid and benzodiazepine dependence | 38 | 11.0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Cannabis, opioid and other substance dependence | 17 | 4.8 | 0 | 0 | |

| Opioid, benzodiazepine and other substance dependence | 17 | 4.8 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 165 | 47 | 27 | 16.1 | |

| Polysubstance dependence | 38 | 11.0 | 6 | 3.6 |

The present study compared only DPD having problem of substance disorder with those not having problem of substance disorder regarding prevalence of psychiatric morbidity. The rationale to include only male prisoners in the study was based on the fact that substance use in general population is known to occur more frequently in men than women.21 Also prevalence of DPD4,22 and rate of conviction in females is less, and by including females required sample size would have become large, which was not feasible. The results therefore, can be generalized only for male population.

Patients with lifetime diagnosis of either psychosis or BPAD were excluded from the study as reliability of personality measurement in those suffering from psychosis is not clear.23 Hence overall psychiatric morbidity is likely to be much higher than that in the current study.

Information on NPM, substance use and DPD was based on self report. Although some participants might have minimized their levels of substance use, earlier methodological studies on this issue4 have shown that collateral reports do not necessarily indicate higher substance use levels when compared with self report. Participants with cognitive impairment and/or co-morbid severe medical illness and who were not co-operative for the interview were planned to be excluded as this could have hampered the assessment. However no exclusion in the study was required on the above account.

In the current study no attempt to rate severity of PD was done though according to earlier study only small minority (probably one in 20) of PD cases suffer from severe PD.24 Only participants above 18 years of age were included in the study because though personality related patterns are usually evident during late childhood or adolescence, but the requirement to establish their stability and persistence restricts the use of the term ‘disorder’ for adults.25

The current study finding was consistent with previous study finding of young and poorly educated people having highest prevalence of DPD.26

Those participants with NPM were more likely to use three or more than three substance at a time but because of both drug use pattern and type of PD being heterogeneous in nature, in current sample size it was beyond scope of this study to draw conclusion on relation of NPM with pattern of individual substance use and vice versa. This issue can be better addressed in future study with larger sample size focusing on specific type of substance use or NPM. SDS score of study participants in this study was similar to earlier study SDS score (mean±SD: 10.2±1.7)27 in prisoners admitted for deaddiction at same centre. The latter study had not taken PD into consideration, and on the basis of the findings of these two studies it cannot be conclusively proclaimed whether DPD has any impact on severity of substance dependence.

The prevalence of alcohol dependence of 59.8% in the current study is much higher than earlier studies’ finding of alcohol abuse and dependence rate of 11.5–30% in male prisoners.28,29 Still higher prevalence rate of 69.2% was present in study participants suffering from psychiatric morbidity. Other drugs also showed similar higher rates of consumption.

Study findings provide some evidence to support the possibility raised in earlier study that given high co-morbidity of PD with AXIS I disorders and especially high odd ratios of PD with AXIS I co-morbidity, the possibility exists that PD affects the onset, persistence and severity of co-morbid AXIS I disorders.30 Questions in this regard can be better answered in future longitudinal epidemiological research on PD.

There is a high rate of comorbidity1,3–6 between personality disorders.31 In the current study, participants suffering from other disorders were not excluded as it would have required much higher sample size which was not possible in this study setting. Possibility of study finding having been influenced by other PD cannot be completely ruled out.

Generally, when a person (or a prisoner) gets old, it may lead to give her/him a kind of maturity that may result in a decrease in prevalence of DPD, and this factor may be the reason for presence of young age participants in our study.32

ConclusionsResults suggest that a high burden of substance-related morbidity exists in DPD population, and treatment of this marginalized population poses a serious challenge to health authorities especially to psychiatrists. Prevalence of NPM in DPD patients suffering from SD is much higher than in non-substance-using population. In study participants with NPM, severity of psychoactive SD was higher than in those not having NPM with more prisoners in this group using three or more substances.

Limitations- (1)

Limitations of the study include its generalizability. This was a hospital-based study conducted on male prisoners and results cannot be applied to the general population, women and children.

- (2)

Results are subjected to possible recall bias due to the self-reported nature of this study. Author has reduced this potential bias by the using validated self-report measures.

- (3)

DPD diagnosis was based on a single instrument, and being a prison setting with its legal limitations it was not possible to interview family members or other informants, who could have provided additional information.

There is no conflict of interest in this study.

I gratefully acknowledge the help provided by Central Jail (CJ) staff, especially Ms. Vimla Mehra (Director General, CJ). The Office of Director General granted permission to publish this paper, but it should be emphasized that the opinion expressed belonged to me and did not necessarily imply any official agreement.