Several studies have addressed the relationship between bipolar disorder and meteorological variables, but no previous review focusing on the influence of a wide range of meteorological variables on bipolar disorder has been published. The aim of this study is to conduct a systematic review about the influence of weather on the clinical course of bipolar disorder patients.

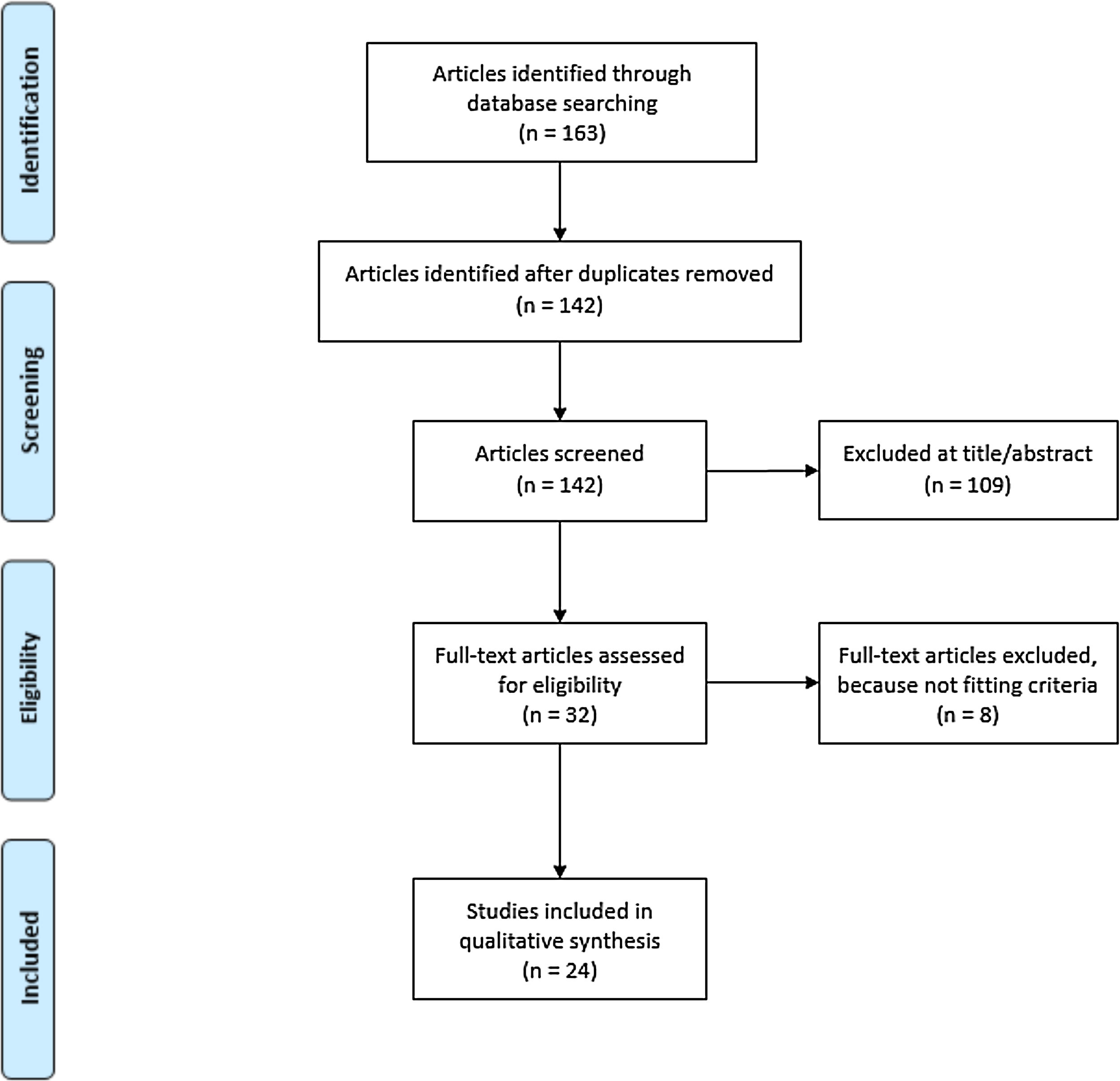

MethodsFollowing PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines, the main electronic medical databases were searched in February 2020, and studies were screened based on the eligibility criteria. 24 studies were selected for qualitative synthesis. Most of them were observational retrospective studies based in medical records.

ResultsThe most studied meteorological variables were temperature and sunlight, and the most studied clinical outcomes were hospital admissions. Significant correlations were found between temperature and sunlight and clinical outcomes, although the findings were heterogeneous. Higher temperatures may trigger bipolar disorder relapses that require hospital admission, and higher expositions to sunlight may increase the risk of manic episodes.

ConclusionMeteorological variables seem to have an influence in the course of bipolar disorder, especially temperature and sunlight, although further studies are needed to clarify this possible relationship.

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a chronic mental disorder affecting mood regulation and characterized by affective episodes (manic, hypomanic or depressive), alternating with periods of euthymia. The prevalence of BD is estimated to be over 1% worldwide,1 has a great impact in quality of life and functioning and is one of the most relevant causes of disability.2

Patients with BD may have chronobiological and circadian rhythm disturbances even when they are euthymic,3,4 higher risk of recurrence when travelling between different meridians due to jet lag5 or abnormalities in ACTH and cortisol secretion.6 Furthermore, previous literature suggested that BD patients may suffer a seasonal pattern when looking at rates of hospitalisation or occurrence of mood symptoms.7 Some neurobiological hypotheses have been suggested, but causes of this phenomena have not been clearly identified.8

Some authors have suggested that meteorological variables may act as mediators explaining circadian alterations and seasonal pattern in BD.9 The influence of weather on mood and mental health has been demonstrated in several studies.10–15 For instance, it has been reported that higher temperature increases the risk of suicide in several countries.10 Furthermore, light therapy could improve the effectiveness of pharmacological treatment of depression.11 Taking into account that BD follows a seasonal pattern, if meteorological variables influence mental diseases, the weather may have an impact on clinical outcomes in BD patients. A better understanding of the influence of meteorological variables on BD would also allow progress in the understanding and management of this disease.

To our knowledge, only a systematic review conducted in 2014 that analysed seasonality of BD included a section dealing with the influence of some few and specific climatic variables,7 but no previous review focusing on the influence of a wide range of weather variables on BD has been published. The aim of this review is to summarise the evidence available on the influence of different meteorological variables on the clinical course of BD.

MethodsPreferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA)12 guidelines were used for this systematic review.

Eligibility criteriaCriteria for inclusion and exclusion of the studies were the following:

- a)

Characteristics of participants: Studies were included if they were conducted on adult patients with a diagnosis of BD type I, II or other specified type (such as rapid cycling), and if the diagnosis was based on standardized diagnostic criteria (DSM or ICD) or if the diagnosis method was detailed and based in previously validated instruments.

- b)

Characteristics of exposures: Studies were included if they provided objective measurements of any type of meteorological variables, defined as atmospheric characteristics or atmospheric phenomena related to weather. This includes variables such as temperature, intensity of sunlight, hours of sunlight, precipitation, humidity, atmospheric pressure, wind, or cloudiness.

- c)

Characteristics of outcomes: Studies were included if they measured clinical outcomes in BD, such as rates or length of hospitalisation, mood state and incidence or duration of affective episodes (either depressive, manic or mixed). Furthermore, these outcomes should have been assessed using a clinical interview, validated scales or extracted from medical records, or by other validated methods that should be clearly specified. Those articles focusing exclusively on the onset for BD and not considering outcome measures were not included in this review.

- d)

Characteristics of comparators: No restrictions were applied for control groups, although studies should be focused on BD patients. In line with this, studies were included if they used a healthy control group, other affective or non affective disorder groups as controls, or even if they did not use control group. However, those studies that analysed the impact of meteorological variables in mental health diseases but did not include BD patients or patients with affective disorders as the main group of study were not included.

- e)

Characteristics of design: No restrictions were applied regarding the design of the studies. However, single-patient studies, such as case reports, or articles that were not patient-based, such as letters to the editor or narrative reviews, were not included.

- f)

Characteristics of the articles: Studies were included if they were written in English or Spanish.

The main source of information was Pubmed (and its section called “related articles”). The databases Web of Science, PsycINFO y Cochrane Library were also used.

Searches were made using the following keywords in PubMed, accessed on 15th February 2020: “Bipolar disorder AND Weather”. ‘All fields’ was selected, no other filters were applied. Searches were conducted in English.

Data collectionA total of 96 results were found in Pubmed, 15 in PsycINFO, 0 in Cochrane Library, 48 in Web of Science, and 4 in “related articles” Pubmed section. Of 163 articles found initially, 142 were selected when duplicates were removed. During the first stage, studies were examined by one author with regard to inclusion criteria previously defined, after reading the title and the abstract. A second independent evaluator was consulted when it was unclear if an article met the inclusion criteria. After this screening, 109 articles were excluded. During the second stage, 32 of the 33 remaining studies were assessed on eligibility criteria after reading the full text. The authors were unable to access one full text of one of the articles, so it was not possible to assess whether that article met the eligibility criteria and it was not included in the qualitative synthesis. Finally, 24 articles were eligible for the qualitative synthesis.

After these stages, data were collected on the following characteristics: year of publication, country, type of design, profile of patients included, sample size, diagnostic criteria used for inclusion in the study, meteorological variables studied, outcomes and main limitations of the study. An overview of the study procedure is provided in a flow chart in Fig. 1.

Risk of bias in individual studiesIn order to assess the risk of bias in the studies reviewed, the Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Nonrandomized Studies (RoBANS)13 was used. This tool includes the assessment of the following elements: participant selection, confounding variables, exposure measures, blinding of results, incomplete results, and selective publication of results.

Quality assesmentEvaluated data were handled and compared by a single author using a validated checklist for epidemiological studies.14 This instrument provides a 27-item checklist appraising a range of methodological features of the study, such as the objective definition, the sample size, the recruitment methods, the reliability of the methodological definitions, the comparability between groups, statistical analysis and results, and the implications and overall generalizability of the results.

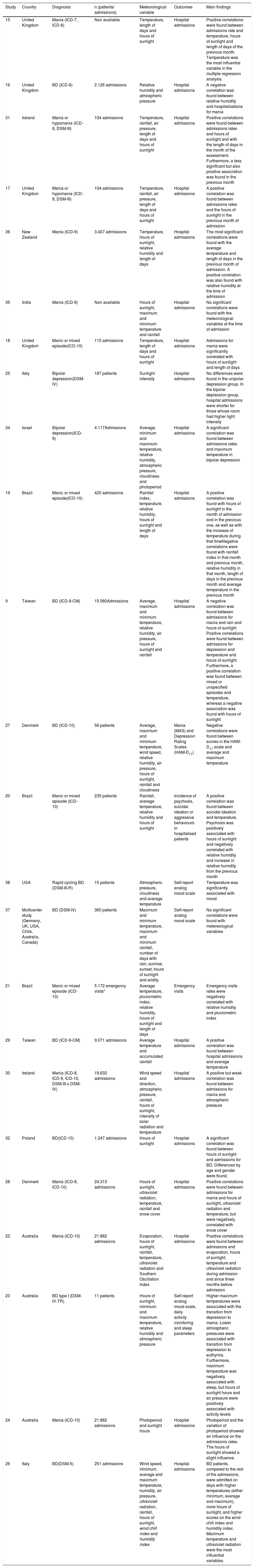

ResultsDescriptive characteristics of the studiesA total of 24 articles were selected for qualitative synthesis. Studies included and their main characteristics are presented in Table 1. Publication date of the studies ranged from 1978 to 2019. Four studies were conducted in the United Kingdom,15–18 three in Brazil,19–21 three in Australia,22–24 two in Italy,25,26 two in Denmark,27,28 two in Taiwan,9,29 two in Ireland,30,31 one in Poland,32 one in the USA,33 one in Israel,34 one in India,35 one in New Zealand36 and one was a multicentre study.37 The design of the studies was heterogeneous, with most of them being retrospective studies based in medical records, although there were also prospective cohort studies.23,27,37,38 Two studies focused on bipolar patients with depression, whereas 11 studies focused on patients with mania. One of the articles studied bipolar patients with rapid cycling,38 whereas 10 articles studied patients with BD in general (irrespective of whether or not they presented manic or depressive episodes). Diagnostic criteria used included ICD-7, ICD-8, ICD-9, ICD-10, DSM-III, DSM-IV y DSM-5.

Studies included in the systematic review.

| Study | Country | Diagnosis | n (patients/ admissions) | Meteorological variable | Outcomes | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | United Kingdom | Mania (ICD-7, ICD-8) | Non available | Temperature, length of days and hours of sunlight | Hospital admissions | Positive correlations were found between admissions rate and temperature, hours of sunlight and length of days of the previous month. Temperature was the most influential variable in the multiple regression analysis. |

| 16 | United Kingdom | BD (ICD-8) | 2.126 admissions | Relative humidity and atmospheric pressure | Hospital admissions | A negative correlation was found between relative humidity and hospitalisations for mania |

| 31 | Ireland | Mania or hypomania (ICD-8, DSM-III) | 104 admissions | Temperature, rainfall, air pressure, length of days and hours of sunlight | Hospital admissions | Positive correlations were found between admissions rates and hours of sunlight and with the length of days in the month of the assessment. Furthermore, a less significant but also positive association was found in the previous month |

| 17 | United Kingdom | Mania or hypomania (ICD-8, DSM-III) | 104 admissions | Temperature, rainfall, air pressure, length of days and hours of sunlight | Hospital admissions | A positive correlation was found between admissions rates and the hours of sunlight in the previous month of admission |

| 36 | New Zealand | Mania (ICD-9) | 3.407 admissions | Temperature, hours of sunlight, relative humidity and length of days | Hospital admissions | The most significant correlations were found with the average temperature and length of days in the previous month of admission. A positive correlation was also found with relative humidity at the time of admission |

| 35 | India | Mania (ICD-9) | Non available | Hours of sunlight, maximum and minimum temperature and rainfall | Hospital admissions | No significant correlations were found with the meteorological variables at the time of admission |

| 18 | United Kingdom | Manic or mixed episode(ICD-10) | 115 admissions | Temperature, length of days and hours of sunlight | Hospital admissions | Admissions for mania were significantly correlated with hours of sunlight and length of days |

| 25 | Italy | Bipolar depression(DSM-IV) | 187 patients | Sunlight intensity | Hospital admissions | No differences were found in the unipolar depression group. In the bipolar depression group, hospital admissions were shorter for those whose room had higher light intensity |

| 34 | Israel | Bipolar depression(ICD-9) | 4.117Admissions | Average, minimum and maximum temperature, relative humidity, atmospheric pressure, cloudiness and photoperiod | Hospital admissions | A significant correlation was found between admissions rates and maximum temperature in bipolar depression |

| 19 | Brazil | Manic or mixed episode(ICD-10) | 425 admissions | Rainfall index, temperature, relative humidity, hours of sunlight and length of days | Hospital admissions | A positive correlation was found with hours of sunlight in the month of admission and in the previous one, as well as with the increase of temperature during that timeNegative correlations were found with rainfall index in that month and previous month, relative humidity in that month, length of days in the previous month and average temperature in the previous month |

| 9 | Taiwan | BD (ICD-9-CM) | 15.060Admissions | Average, maximum and minimum temperature, relative humidity, air pressure, hours of sunlight and rainfall | Hospital admissions | A negative correlation was found between admissions for mania and rain and hours of sunlight Positive correlations were found between admissions for depression and temperature and hours of sunlight. Furthermore, a positive correlation was found between mixed or unspecified episodes and temperature, whereas a negative association was found with hours of sunlight |

| 27 | Denmark | BD (ICD-10) | 56 patients | Average, maximum and minimum temperature, wind speed, relative humidity, air pressure, hours of sunlight, rainfall and cloudiness | Mania (MAS) and Depression Rating Scales (HAM-D17) | Negative correlations were found between scores in the HAM-D17 scale and average and maximum temperature |

| 20 | Brazil | Manic or mixed episode (ICD-10) | 235 patients | Rainfall, average temperature, relative humidity and hours of sunlight | Incidence of psychosis, suicidal ideation or aggressive behaviours in hospitalised patients | A positive correlation was found between suicidal ideation and temperature. Psychosis was positively associated with hours of sunlight and negatively correlated with relative humidity and increase in relative humidity from the previous month |

| 38 | USA | Rapid cycling BD (DSM-III-R) | 15 patients | Atmospheric pressure, cloudiness and average temperature | Self-report analog mood scale | Temperature was significantly associated with mood |

| 37 | Multicenter study (Germany, UK, USA, Chile, Australia, Canada) | BD (DSM-IV) | 360 patients | Maximum and minimum temperature, maximum and minimum rainfall, number of days with rain, sunrise, sunset, hours of sunlight and aridity. | Self-report analog mood scale | No significant correlations were found with metereological variables |

| 21 | Brazil | Manic or mixed episode (ICD-10) | 5.172 emergency visits* | Average temperature, pluviometric index, relative humidity, hours of sunlight and length of days | Emergency visits | Emergency visits rates were negatively correlated with relative humidity and pluviometric index |

| 29 | Taiwan | BD (ICD-9-CM) | 9.071 admissions | Average temperature and accumulated rainfall | Hospital admissions | A positive correlation was found between hospital admissions and average temperature |

| 30 | Ireland | Mania (ICD-8, ICD-9, ICD-10, DSM-III o DSM-IV) | 19.632 admissions | Wind speed and direction, atmospheric pressure, rainfall, hours of sunlight, intensity of solar radiation and temperature | Hospital admissions | A positive but weak correlation was found between admissions for mania and atmospheric pressure |

| 32 | Poland | BD(ICD-10) | 1.247 admissions | Hours of sunlight | Hospital admissions | A significant correlation was found between hours of sunlight and admissions for BD. Differences by age and gender were found. |

| 28 | Denmark | Mania (ICD-8, ICD-10) | 24.313 admissions | Hours of sunlight, ultraviolet radiation, temperature, rainfall and snow cover | Hospital admissions | Positive correlations were found between admissions for mania and hours of sunlight, ultraviolet radiation and temperature, but were negatively correlated with snow cover |

| 22 | Australia | Mania (ICD-10) | 21.882 admissions | Evaporation, hours of sunlight, rainfall, temperature, ultraviolet radiation and Southern Oscillation Index | Hospital admissions | Positive correlations were found between admissions and evaporation, hours of sunlight, temperature and ultraviolet radiation during admission and since three months before admission |

| 23 | Australia | BD type I (DSM-IV-TR) | 11 patients | Hours of sunlight, minimum and maximum temperature, relative humidity and atmospheric pressure | Self-report analog mood scale, daily activity monitoring and sleep parameters | Higher maximum temperatures were associated with the transition from depression to mania. Lower atmospheric pressures were associated with transition from depression to euthymia. Furthermore, maximum temperature was negatively associated with sleep, but hours of sunlight hours and air pressure were positively associated with activity levels |

| 24 | Australia | Mania (ICD-10) | 21.882 admissions | Photoperiod and sunlight hours | Hospital admissions | Photoperiod and the variation of photoperiod showed an influence on the admissions rates. The hours of sunlight showed a slight influence. |

| 26 | Italy | BD(DSM-5) | 251 admissions | Wind speed, minimum, average and maximum temperature, humidity, air pressure, ultraviolet radiation, rainfall, hours of sunlight, wind chill index and humidity index | Hospital admissions | BD patients, compared to the rest of the admissions, were admitted on days with higher temperatures (either minimum, average and maximum), more hours of sunlight, and higher scores on the wind chill index and humidity index. Maximum temperature and ultraviolet radiation were the most influential variables. |

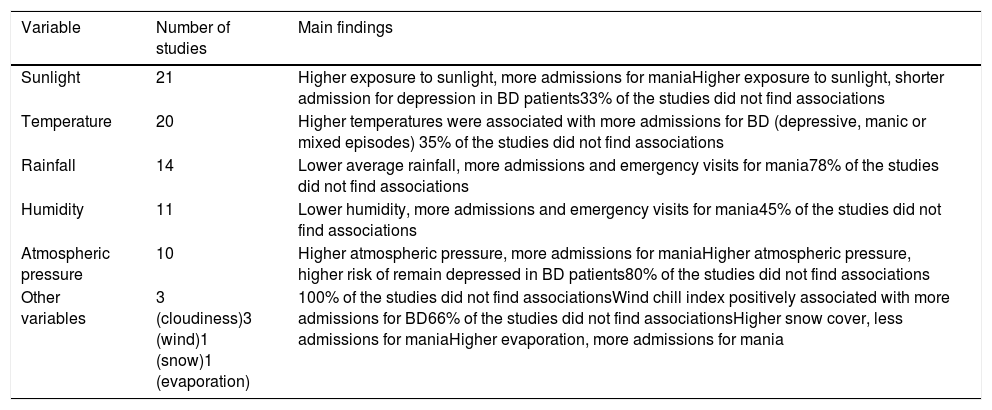

The meteorological variables that were mostly analysed were temperature (e.g., average, maximum or minimum temperature), solar radiation or photoperiod (e.g., intensity of sunlight, hours of sunlight or length of days). Other studies measured variables such as rainfall, humidity, air pressure, cloudiness, wind, snow cover or evaporation. Most of the studies used monthly averages of the different meteorological variables, although some of them used daily data of the variables. Table 2 shows a summary of the main findings of the studies.

Summary of meteorological variables association with BD.

| Variable | Number of studies | Main findings |

|---|---|---|

| Sunlight | 21 | Higher exposure to sunlight, more admissions for maniaHigher exposure to sunlight, shorter admission for depression in BD patients33% of the studies did not find associations |

| Temperature | 20 | Higher temperatures were associated with more admissions for BD (depressive, manic or mixed episodes) 35% of the studies did not find associations |

| Rainfall | 14 | Lower average rainfall, more admissions and emergency visits for mania78% of the studies did not find associations |

| Humidity | 11 | Lower humidity, more admissions and emergency visits for mania45% of the studies did not find associations |

| Atmospheric pressure | 10 | Higher atmospheric pressure, more admissions for maniaHigher atmospheric pressure, higher risk of remain depressed in BD patients80% of the studies did not find associations |

| Other variables | 3 (cloudiness)3 (wind)1 (snow)1 (evaporation) | 100% of the studies did not find associationsWind chill index positively associated with more admissions for BD66% of the studies did not find associationsHigher snow cover, less admissions for maniaHigher evaporation, more admissions for mania |

In terms of the events analysed, most studies used hospital admission rates, without previously delimiting a sample of patients, as outcome measures of the impact of climatic variables on patients. A smaller group of articles used self-report mood scales as outcome measures. One study27 also used scales for mood assessment, other article20 assessed three dimensions of mania (psychosis, aggression and suicidality), and other study25 measured the length of hospitalisations.

Metereological variables and BDTemperatureA total of 20 studies analysed temperature as a meteorological variable. 13 studies found significant correlations with hospital admissions for mania: a positive association with the increase in temperature compared to the previous month19 and a negative association with temperatures in the previous month19,22; a positive association with the average temperature28; a correlation with temperature in the month of admission (which was also found as the best predictor of hospital admissions for mania)15 and a correlation with previous and current month of admission temperature.36

One study found that admissions for bipolar depression but not for unipolar depression were associated with higher maximum temperatures.34 Three studies analysed the whole number of admissions for BD, finding a positive association between admissions, either for mania or bipolar depression, and average, maximum and minimum daily temperature,26 a positive association between admissions for depression or mixed episodes and monthly temperature9 and a positive association between average daily temperature and admissions.29

Two studies used self-assessment mood scales: one of them, conducted prospectively with patients with rapid cycling, showed that daily temperature was the variable that best explained mood variations,33 whereas the other one, with patients with type I BD, found a positive association between maximum daily temperature and transition from depression to mania.23 Another prospective study, using the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D17) and Bech Rafaelsen Mania Rating Scale (MAS), found a negative correlation between HAM-D17 scores and average temperature and maximum temperature in the month of the assessment.27 Furthermore, one study found a positive association between the temperature increase over the previous month and the incidence of suicidal ideation.20

Seven studies did not find a correlation between temperature and any outcome measure for BD.17,18,21,30,31,35,37

Solar radiationThe concept of “sunlight” will include all variables directly related, such as intensity of sunlight, hours of sunlight and length of days or photoperiod. 21 studies of all those included analysed the effect of sunlight. Eight studies evaluated the influence of sunlight in admissions for mania, with the following findings: a correlation with the length of days and with the hours of sunlight in the month before admission15; a positive correlation with the hours of sunlight in the month of admission and the length of days in the month of admission and the month before31; a positive correlation with the hours of sunlight in the month before admission17; a correlation with the length of the days in the month before admission36; a positive correlation with hours of sunlight in the month of admission, as well as a negative correlation with the length of days in the previous month19; a positive association with average ultraviolet radiation28; a positive association with hours of sunlight and with solar radiation in the month of admission, but a negative correlation with ultraviolet radiation in the two and three months before the admission22; and positive associations with photoperiod, change in photoperiod and monthly hours of sunlight.24

Four studies analysed overall admissions for BD. One of them found a correlation between admissions for mania and average of sunlight hours and length of days.18 Another study showed that monthly hours of sunlight were negatively correlated with admissions for manic or mixed/unspecified episodes, and positively correlated with admissions for depressive episodes.9 Other study found an association between hours of sunlight and admissions, which varied depending on age and sex subgroups: in women aged 18–35, a negative association with mania and a positive association with depression were found; in women over 65, a positive association with mania and a negative association with depression and mixed episodes were found; and in men aged 36–65, a positive association with mania and mixed episodes and a negative association with depression were found.32 Lastly, another study found a positive correlation between admissions for BD and hours of sunlight and solar radiation. Furthermore, logistic regression analyses showed that maximum temperature and solar radiation were the most relevant meteorological variables in admissions for BD.26

Two studies showed correlations between sunlight and other clinical parameters. One found that patients with bipolar depression, unlike patients with unipolar depression, had shorter hospitalizations if they were admitted to the east wing of the hospital, which was more exposed to sunlight.25 The other study showed that the incidence of psychosis in the context of manic episodes was positively associated to the hours of sunlight in the month of the admission and the increase in sunlight hours compared to the previous month.20

Seven studies found no significant correlation between sunlight-related variables and clinical parameters related to BD.21,23,27,30,34,35,37

Rainfall14 studies analysed the possible effect of rainfall. Three of the studies found significant negative correlations between admission rates for mania and average rainfall,9 average rainfall in the month of the admission and in the previous month19 and between emergency visits for mania and average rainfall.21

11 of them found no significant correlation between rainfall and different clinical variables.17,20,22,26–31,35,37

Humidity11 studies analysed the effect of humidity (or aridity as the opposite). Six studies reported several significant correlations between humidity and clinical parameters: a negative correlation between psychosis rates in manic episodes and relative humidity in the month of admission and increase in humidity compared to the previous month,20 a positive correlation between daily maximum humidity and hospital admissions for BD,26 a negative correlation between monthly relative humidity and emergency visits rates for mania,21 a correlation between change in humidity and admissions for mania,36 and a negative correlation between admissions for mania and monthly relative humidity19 or relative humidity in the previous weeks.16

However, five of them found no significant correlations.9,23,27,34,37

Atmospheric pressure10 articles analysed the effect of atmospheric pressure. Only two studies found significant correlations: one study found a positive but weak association between daily atmospheric pressure and admissions for mania,30 whereas other study found a negative association between atmospheric pressure at sea level and the transition from a depressed mood to euthymia on self-report scales.23

Eight of them did not find significant correlations.9,16,17,26,27,31,34,38

Other meteorological variablesOther meteorological variables studied were cloudiness, wind, snow and evaporation.

None of the three studies that analysed the effect of cloudiness found significant correlations.27,34,38 Three articles studied the influence of wind in BD. One study found a positive correlation between the wind chill index (perceived decrease in air temperature experienced by the body on exposed skin due to the flow of air) and admission rates for BD, although it is difficult to know if this variable is more associated with wind or temperature.26 Nevertheless, two of them did not find significant correlations).27,30 One study found a negative correlation between the average monthly snow cover (the amount of surface cover by snow) and admission rates for mania.28

Regarding evaporation, one study found a positive correlation between admissions for mania and the average evaporation rate in the month of admission, whereas a negative correlation was found with the average evaporation rate in the previous two and three months. A multivariate analysis in that study found that the most relevant finding was the positive association between admissions for mania and the average evaporation at admission, as well as a negative association with the average temperature of the previous month.22

DiscussionFindings in this review suggest that previous literature has found associations between some meteorological variables and BD. Sunlight and temperature are the variables that show more impact in clinical outcomes such as hospital admissions or mood changes in BD. Concerning sunlight, results of different studies consistently suggested that higher exposure to sunlight would increase mania rates.17,19,22,24,28,31 However, impact on depression was less clear: while one article found that higher exposure to sunlight was associated with admissions for bipolar depression,9 other article found that higher exposure improved recovery in patients admitted for bipolar depression.25 This study is congruent with previous findings suggesting that light therapy would improve bipolar depression39 or other patients with depression.11 It has been suggested that latency period for the impact of sunlight in mood would range from a few days to two months, although this remains unclear since evidence to prove this is still scarce.

Higher temperature appears to increase the risk of a manic or depressive episode,9,19,22,26,28,29,34 and even suicidal ideation,20 which has been previously suggested in other studies.40 Regarding the latency period when analysing the effect of temperature on mood, studies suggested that temperature could have an immediate effect on mood. It is also suggested that in case of certain degree of latency, it would not extend beyond the month before the mood variation.

Regarding other meteorological variables, the associations found were not consistent, despite being of interest. For instance, although most of the studies analysing the impact of rainfall found no significant correlations with clinical outcomes in BD,17,20,22,26–31,35,37 three studies found that increases in rainfall were associated with a lower incidence of mania.9,19,21 Results were inconclusive regarding humidity, since around half of the studies found no associations with clinical outcomes in BD.9,23,27,34,37 However, in the field of meteorology, it is well known that humidity has a clear influence on thermal sensation: higher humidity is associated with greater sensation of heat. This association, measured by the temperature-humidity index, could play a role in the relationship between humidity and mood, but was only measured in one of the articles included.26

Atmospheric pressure was not found as relevant in most of the studies9,16,17,26,27,31,34,38 even when higher pressures may be generally associated with clear skies and greater sunlight as a consequence. This suggests the relevance of considering this confounding association when interpreting data or designing future studies. When some of the studies included in this review used multivariate analysis to better control this possible covariations, temperature and solar radiation were found as the most influential variables.15,18,19,21,26,28,36

Several neurobiological mechanisms are likely to be involved in the relationship between weather and mood. The role of melatonin and some monoaminergic neurotransmitters, mainly serotonin and dopamine deserve consideration. It has been observed that seasons and meteorological variables may have an impact in dopamine and serotonin levels.41 Sunlight tends to increase serotonin levels,42 which could be associated with higher mania rates and improvement in depressive episodes suggested by this review. Regarding melatonin, there are melanopsin-containing ganglion cells in the retina that are intrinsically photosensitive. When this cells are activated they connect through the retinohypothalamic tract to the suprachiasmatic nucleus.43 The suprachiasmatic nucleus, located in the anterior region of the hypothalamus, acts as the central clock regulating circadian rhythms. This nucleus also connects to the pineal gland, regulating melatonin secretion, so that the incidence of light on retinal ganglion cells results in an inhibition of melatonin secretion.44,45 Melatonin influences several biological functions including sleep,46,47 so deregulation of the sleep/wake cycle may have a role in explaining the influence of sunlight on BD. Furthermore, temperature and humidity could worsen quality of sleep.48 These findings suggest that sleep disturbances might be associated with a common pathway between meteorological variables and mood in BD. In fact, one of the studies included in this review observed that higher temperatures were negatively associated with sleep, and that hours of sunlight and air pressure were positively associated with patients’ activity levels. Furthermore, they also found that sleep and activity had a significant effect on mood, so both parameters could act as mediators in the influence of meteorological variables on BD.23 Other factors can contribute to the relationship between weather and mood in BD, such as vitamin D,49 cortisol secretion,6 physical activity50 and several psychosocial variables that may be associated with weather, such as social relationships, employment, festive events or psychosocial stress.

This study has some practical implications. Firstly, our results contribute to a better understanding of what variables have an impact in BD recurrences, suggesting further lines of research from a neurobiological perspective. Secondly, these results may contribute to potential treatments. Thirdly, having in mind the relationship between meteorological variables and clinical outcomes, clinicians, patients and relatives would be more prepared to assess when an increased risk of relapse is more likely, which could lead to closer follow-up on patients at risk or to plan health resources accordingly.

Even though this is the first systematic review analysing the impact of meteorological variables in BD, it has several limitations that should be noted. The articles included were heterogeneous regarding the design, the sample size, the diagnostic criteria, the meteorological variables analysed and how they were measured, the outcomes or the statistical analyses used. Furthermore, due to the different diagnostic criteria, ranging from DSM-III17,30,31,38 or ICD-715 to DSM-526 or ICD-10,18–22,24,27,28,30,32 patient samples are likely to vary between studies.

Most studies used a retrospective design based on medical records,9,15–22,24,25,28–32,34–36 which allows for correlational analysis, but has limitations for demonstrating causality. In addition, the few studies that were prospective, which is a more powerful design when looking for causality, used smal sample sizes (n = 5627, n = 1533 y n = 1123) and only one of them overcame a hundred of patients (n = 360).37 Furthermore, they used self-report mood scales as outcome measures, which has limitations in the identification of manic episodes, due to the lack of insight commonly associated.

Furthermore, most of these studies analysed admission rates as outcome measure.9,15,16–19,22,24,26,28–32,34–36 This may underestimate the number of BD recurrences, since some manic episodes, but particularly many depressive episodes, do not necessarily require hospital admissions. In fact, the use of this clinical parameter could be inaccurate, due to its potential for detecting only the most serious episodes. Furthermore, there is often a time lag between the onset of a recurrence and admission for that affective episode what could confound the temporal association between meteorological variables and the actual onset of an affective episode.

Insisting on the issue of the samples, some studies used the number of admissions for each mood episode, irrespective of the number of patients, whereas other studies analysed a defined number of patients. Considering that BD patients may be admitted several times, those studies that only provided the number of admissions, instead of the overall number of patients, used a different criteria to define sample size compared to those studies that did provide the exact number of patients analysed. Furthermore, two studies did not provide the sample size.

In terms of measurement of meteorological variables, most of the studies analysed monthly averages of these variables.9,15,17–22,24,27,28,31,32,34–37 This could lead to a lack of precision when associating these measurements with outcomes, since clinical outcomes such as mood symptoms variation may vary following a daily pattern. Furthermore, there was heterogeneity in the studies regarding the time frame that was used for the analysis of meteorological variables as triggers of mood episodes, considering that a latency period should be taken into account when analysing this relationship. It is noteworthy that all the included studies, except for one of them,25 used meteorological measures provided by meteorological or statistical institutions. This methodology could be inaccurate since it does not take into account individual exposure to local meteorological variables for each participant. It is also difficult to know the actual degree of exposure of each case to variables such as temperature, solar radiation, or humidity; at least without considering other relevant variables such as the amount of time the patient spends outdoors. Furthermore, only a minority of the studies examined the influence of mediators between meteorological variables and clinical course, such as physical activity or sleep.23,37

Finally, the authors were unable to have access to a full text of one of the articles that met the inclusion criteria, even after a request was made to the author, so that data could not be included in the review.51

Because of the aforementioned limitations, it is strongly encouraged to conduct further studies in this area, especially those using a prospective design and larger sample sizes, with a daily measurement of meteorological variables associated with clinical outcomes. The possible influence of a latency period and other confounding factors (e.g., actual time spent outdoors) should be considered.

ConclusionsMeteorological variables seem to have an impact on mood in BD patients. Sunlight and temperature are the most studied variables and are also those that appear to have the greatest influence on clinical outcomes. Higher exposure to sunlight may increase the incidence of manic episodes while higher temperatures seem to worsen the course of BD patients, influencing both manic and depressive polarities. However, more carefully designed studies are needed in order to better understand the influence of these variables as well as other meteorological variables.

Ethical considerationsThe authors declare that have ethically conducted the review, paying attention to all perspectives of original studies, reflecting search biases and communicating the results objectively.

FundingThis review did not receive any funding.

Conflicts of interestNone of the authors declare conflicts of interest for this study.